Additional insights from our financial audits

Additional insights from our financial audits

Significant projects with information technology components

Federal organizations rely on information technology (IT) systems to deliver services to Canadians, process financial transactions, and prepare financial reports. These systems must be reliable in order for organizations to deliver programs successfully and also to have credible financial reports that they base decisions on and present to Parliament.

This year, our financial audits made us aware of about 30 significant projects with IT components—planned or underway—that affect financial reporting at various federal organizations, including Crown corporations. During our financial audits, we noted new projects as well as projects that were completed during the year. The current or planned projects we are aware of are significant, because they involve systems that are undergoing major conversion or replacement as well as changes to IT management in some organizations. Examples include the following:

- The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) has a multi-year initiative to transform the collection of tax and duty for goods imported into Canada. The CBSA Assessment and Revenue Management project is expected to modernize and streamline the importing of commercial goods into Canada. The project is expected to be completed in spring 2021.

- Employment and Social Development Canada has an initiative known as the Benefits Delivery Modernization that is expected to improve Canadians’ access to services and benefits, including speeding up the application processes. This initiative aims to renew business processes and technology for Employment Insurance, Old Age Security, and the Canada Pension Plan to transform the way benefits are delivered. The department informed us that the definition phase of the initiative started in 2017 after it researched best practices and lessons learned from organizations that had undergone similar transformations. Given that full approval and funding have yet to be received, the timelines have not yet been defined. Once the initiative is approved, the department expects to implement various projects over several years.

- Employment and Social Development Canada, which is responsible for the Canada Student Loans Program, is implementing a new IT system being developed by a third party that is expected to enhance the client-service experience and will manage the program across the entire lending cycle. The new system is being launched in phases. It started in 2018, additional features were made available for students in 2019, and further enhancements are expected to be implemented through the end of 2021. The program provides loans and grants to eligible students to help them access and afford post-secondary education. The program also administers loans and grants to students on behalf of some provinces.

- The Canada Revenue Agency has a multi-year project underway to significantly modify the systems for processing individual tax returns to address a major IT sustainability risk. This project, known as the T1 Systems Redesign, began in the 2013–2014 fiscal year and is being implemented in phases. It is expected to be completed in the 2019–2020 fiscal year.

The government is exploring alternatives to replace the Phoenix pay system. This initiative was not at the project stage but could become a major project.

The risks and challenges involved in projects with IT components depend on their type and complexity. Examples of significant risks often seen in such projects include

- inappropriate governance and project management

- incomplete or inaccurate business case

- poor data quality

- system functions not working as intended or unforeseen impacts on other systems

- lack of organizational capacity

- issues with change management, including training of employees or end users

It is important for federal organizations to implement good governance and project management practices to manage the risks and challenges of significant and complex projects with IT components. In 2019, the Treasury Board approved new project management policies that focus on clear accountabilities, capacity building, and risk management. Among other things, these new policies were the government’s response to a rapidly changing technological environment and the need for more agility. One of the key areas of the new policies is to require organizations to clearly define and realize expected outcomes and benefits.

Our Commentary on the 2017–2018 Financial Audits listed some commonly used practices to help manage the risks and challenges of these types of projects. It also included questions parliamentarians could ask federal organizations planning significant and complex projects with IT components to ensure they anticipate and address possible issues.

How voted expenditures are managed by departments and agencies

Every year, Parliament authorizes expenditures for departments and agencies through the Main Estimates process. Approved spending or authorized expenditures are called voted expenditures. Departments and agencies decide how to manage their voted expenditures to achieve the results they expect in a cost-effective manner, subject to applicable requirements such as policies and conditions imposed by the Treasury Board. More information on how Parliament approves government spending is in our Commentary on the 2017–2018 Financial Audits.

During the fiscal year, the spending plans of departments and agencies may change as their needs evolve or circumstances change. They may request changes to their voted expenditures after Parliament has approved the Main Estimates. The government may table 1 or more Supplementary Estimates in order to seek parliamentary approval of new spending measures. Two additional situations may occur:

- A transfer between votes within an organization or between departments and agencies. The government may transfer funding between departmental votes or from a department or agency to another for a variety of reasons.

- A transfer between fiscal years (known as reprofiling). A department or agency may need to revise the timing of when expenditures will occur to implement an initiative. In that case, the department or agency may ask the Department of Finance Canada to move funding between fiscal years.

Every year, Parliament also approves amounts included in central votes managed by the Treasury Board. A central vote gives authority to the Treasury Board to allocate funds from the vote directly to departments when the amounts and conditions have been satisfied. One example is the government contingencies central vote. When a department or agency needs additional money to meet urgent or unforeseen requirements, it may ask the Treasury Board to access funds from the government contingencies central vote.

The actual costs of an organization’s activities can be lower than the amounts forecast in the voted expenditures. In these cases, at the end of the fiscal year, most departments or agencies may carry forward into the following year up to 5% of voted operating expenditures and up to 20% of voted capital expenditures that were not spent during the fiscal year.

At the end of the fiscal year, any unspent voted expenditures remaining after reprofiling and carrying amounts forward will lapse, meaning they are no longer available for spending by departments and agencies.

After the end of the fiscal year, each department and agency reports through the Public Accounts of Canada on the status of the funds approved by Parliament and the amounts it spent during the fiscal year (Exhibit 9).

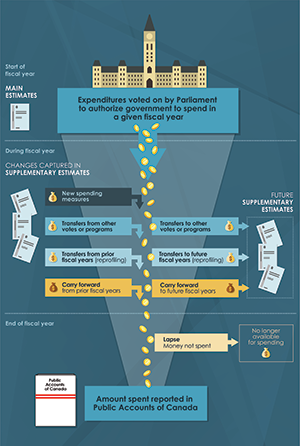

Exhibit 9—How voted expenditures are managed in a fiscal year

Exhibit 9—text version

This graphic shows how voted expenditures are managed from the start of a fiscal year to the end of a fiscal year.

At the start of a fiscal year, the Main Estimates report the expenditures voted on by Parliament to authorize the government to spend in a given fiscal year.

During the fiscal year, the changes are captured in the supplementary estimates. Several changes affect the amount spent that is reported at the end of the fiscal year in the Public Accounts of Canada. These changes are new spending measures, transfers from other votes or programs, transfers from prior fiscal years (also known as reprofiling), and amounts carried forward from prior fiscal years.

Several changes during the fiscal year will affect the amount of future supplementary estimates. These changes are transfers to other votes or programs, transfers to future fiscal years (also known as reprofiling), and amounts carried forward to future fiscal years.

At the end of the fiscal year, any money not spent lapses, meaning that it is no longer available for spending.

Public sector pension plans

The Government of Canada sponsors a number of defined benefit pension plans covering substantially all federal public service employees, as well as members of the Canadian Armed Forces, members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, members of Parliament, and others. In addition, some Crown corporations and other federal organizations maintain their own defined benefit pension plans covering substantially all of their employees.

The federal public sector pension plans have a large impact on the government’s financial statements. In the government’s 2018–2019 statement of financial position, the public sector pension liability totalled close to $169 billion.

Given the size of these liabilities and their potential impact on the government’s finances, it is important to understand how they are presented in the financial statements, which have a wealth of information about pension plans. We created a video that explains basic concepts about pension plans and how defined benefit pension plans are presented in the financial statements.

Life cycle of a government loan receivable

The federal government provides loans to individuals, organizations, and other governments. The government’s 2018–2019 consolidated statement of financial position shows $26 billion in loans, investments, and advances (other than those to other Government of Canada–related organizations), with a provision for bad debt of more than half of that amount (Exhibit 10).

Exhibit 10—Amounts of government lending reported in the statement of financial position

| Type of lending reported | Amount of lending (in $ billions) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 2018–2019 fiscal year | 2017–2018 fiscal year | |

| Loans and advances to national governments and international organizations | $25 | $24 |

| Other loans | $9 | $9 |

| Loans under the Canada Student Loans Program | $21 | $20 |

| Less: provision for bad debt (also known as valuation allowance) | $29 | $27 |

| Total other loans, investments, and advances | $26 | $26 |

Source: 2018–2019 Public Accounts of Canada—Volume 1, Section 9

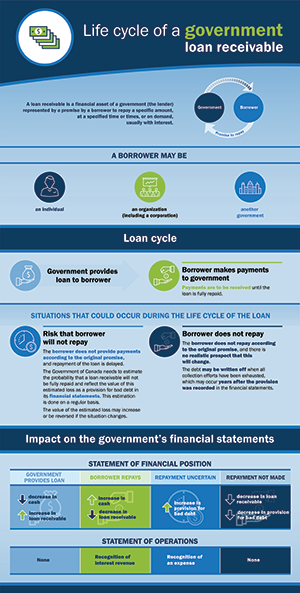

Exhibit 11 provides an overview of the life cycle of a loan receivable, including the impact of the provision for bad debt and the write-off of a loan receivable on the financial statements of the Government of Canada. For example, loans issued under the Canada Student Loans Program represented a significant balance. In the 2018–2019 fiscal year, loans and interest receivable for this program totalling $579 million were written off or forgiven.

Exhibit 11—How a government loan receivable affects the government’s financial statements

Exhibit 11—text version

The graphic shows an overview of the life cycle of a loan receivable, including the impact of the provision for bad debt and the write-off of a loan receivable on the financial statements of a government.

A loan receivable is a financial asset of a government (the lender) represented by a promise by a borrower to repay a specific amount, at a specified time or times, or on demand, usually with interest. A borrower may be an individual, an organization (including a corporation), or another government.

A loan cycle includes a government providing a loan to a borrower, and the borrower making payments to the government. The payments are to be received until the loan is fully repaid.

During the life cycle of the loan, two situations may occur: the risk that the borrower will not repay, or the borrower does not repay.

- With the risk that the borrower will not repay, the borrower does not provide payments according to the original promise, and the repayment of the loan is delayed. The Government of Canada needs to estimate the probability that a loan receivable will not be fully repaid and reflect the value of this estimated loss as a provision for bad debt in its financial statements. This estimation is done on a regular basis. The value of the estimated loss may increase or be reversed if the situation changes.

- In the other situation, the borrower does not repay according to the original promise, and there is no realistic prospect that this will change. The debt may be written off when all collection efforts have been exhausted, which may occur years after the provision was recorded in the financial statements.

The impact on the government’s financial statements of a loan cycle is the following.

When the government provides a loan, the statement of financial position shows a decrease in cash and an increase in the loan receivable. There is no impact on the statement of operations.

When the borrower repays, the statement of financial position shows an increase in cash and a decrease in loan receivable. The statement of operations recognizes interest revenue.

When repayment is uncertain, the statement of financial position shows an increase in the provision for bad debt, and the statement of operations recognizes an expense.

When repayment is not made, the statement of financial position shows a decrease in the loan receivable and a decrease in the provision for bad debt. There is no impact on the statement of operations.