2018 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 3—Conserving Biodiversity

2018 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Report 3—Conserving Biodiversity

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- National leadership

- Environment and Climate Change Canada did not provide effective leadership and did not effectively coordinate the actions required to achieve Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets

- Environment and Climate Change Canada did not compile comprehensive information to report on performance and progress toward the 2020 biodiversity targets

- Progress and results

- National leadership

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 3.1—Species populations declined in Canada over three decades

- 3.2—Some ecosystems vital to plants and animals in Canada have declined significantly

- 3.3—Performance indicators were established for the six national biodiversity targets examined

- 3.4—Responsible federal departments and agencies were unlikely to fully meet the biodiversity target for protected areas (target 1)

- 3.5—The Government of Canada launched a new management approach to improve quantitative and qualitative results for land and water protection in Canada

- 3.6—Delays in implementing the Species at Risk Act increased threats to the boreal woodland caribou

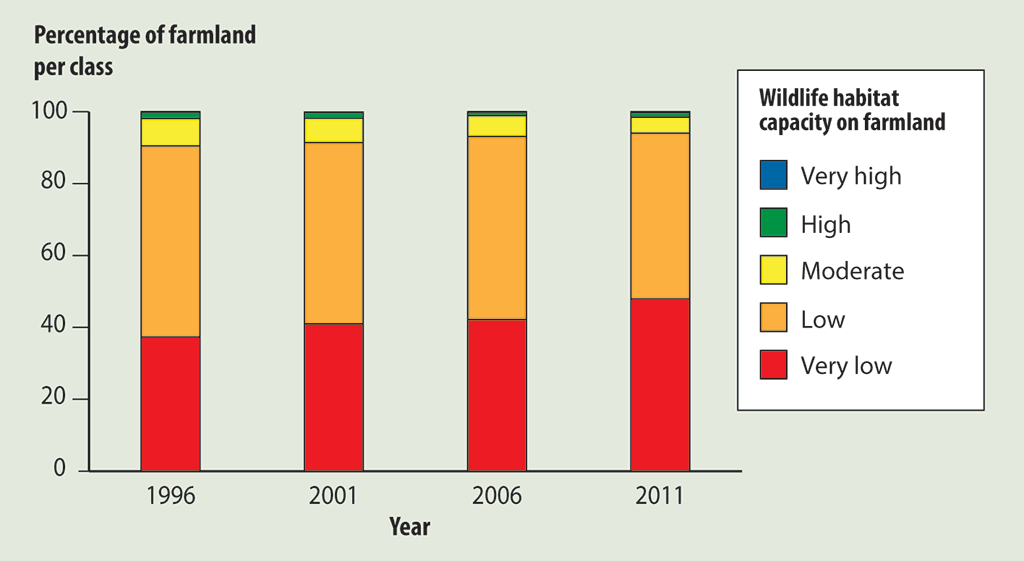

- 3.7—Wildlife habitat capacity on farmlands declined by 10% between 1996 and 2011

- 3.8—Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada did not assess the effect of environmental farm plans on biodiversity conservation

Introduction

Background

3.1 Biological diversity (or biodiversity) refers to the variety of species, ecosystemsDefinition i, and ecological processes found on Earth. Canada is home to approximately 80,000 species of plants and animals. Canadian biodiversity is spread across a wide range of landscapes and ecosystems, but the greatest biodiversity is found in the southern areas where most Canadians live.

3.2 Biodiversity is one of the foundations for Canada’s social and economic prosperity. Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and ecotourism rely on healthy ecosystems and contribute billions of dollars to the Canadian economy. Biodiversity provides ecosystem servicesDefinition ii that contribute to Canadians’ health through food, medications derived through natural sources, and recreation in natural settings.

3.3 Canada’s biodiversity is under pressure from urbanization, economic growth, climate change, and our reliance on natural resources. A key challenge for all stakeholders is to balance conserving biodiversity with economic development.

3.4 In 1992, Canada signed the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. This legally binding treaty recognized that the global decline of biodiversity is one of the most serious environmental issues facing humanity. Countries that signed the Convention committed to conserving biological diversity, using its components sustainably, and sharing the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources fairly and equitably.

3.5 As a signatory to the Convention, Canada had to prepare a national strategy for conserving biodiversity. The Canadian Biodiversity Strategy, developed in 1995, was Canada’s response to this obligation. The strategy recognized existing constitutional and legislative responsibilities for biodiversity in Canada. It emphasized

- the importance of intergovernmental cooperation to create policy, and

- management and research conditions that were needed to advance ecological management.

Federal, provincial, and territorial governments committed to pursuing the strategy’s implementation according to their policies, plans, priorities, and fiscal capabilities.

3.6 In April 2002, the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity made a commitment to significantly reducing the rate of biodiversity loss at the global, regional, and national levels by 2010. The 2010 target was not achieved. In 2010, in the Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 report, the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity stressed the importance of taking timely action, over the next decade or two, to protect the stability of environmental conditions critical to human life. The Parties to the Convention set new targets for 2020, called the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. These targets form part of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020, adopted as a global framework for action on biodiversity.

3.7 The Convention on Biological Diversity encouraged countries to set national targets based on the Aichi targets. In 2015, Canada announced 19 national biodiversity targets, under four overarching goals:

- Goal A: “By 2020, Canada’s lands and waters are planned and managed using an ecosystem approach to support biodiversity conservation outcomes at local, regional, and national scales.”

- Goal B: “By 2020, direct and indirect pressures as well as cumulative effects on biodiversity are reduced, and production and consumption of Canada’s biological resources are more sustainable.”

- Goal C: “By 2020, Canadians have adequate and relevant information about biodiversity and ecosystem services to support conservation planning and decision-making.”

- Goal D: “By 2020, Canadians are informed about the value of nature and more actively engaged in its stewardship.”

3.8 Recent public reports have highlighted some of Canada’s biodiversity challenges (Exhibit 3.1).

- In 2016, the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, created by the governments of Canada, the United States, and Mexico, reported that one third of all North American bird species needed urgent conservation action. Some species had declined by nearly 70% since 1970.

- In 2017, Environment and Climate Change Canada stated that more than 500 plant and animal species were listed under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, and the list was growing.

- In 2017, the World Wildlife Fund reported declines in Canada’s wildlife since 1970. The report also stated that wildlife populations listed as at risk declined at a faster rate between 2002 and 2014 than between 1970 and 2002, despite new protections under the Species at Risk Act.

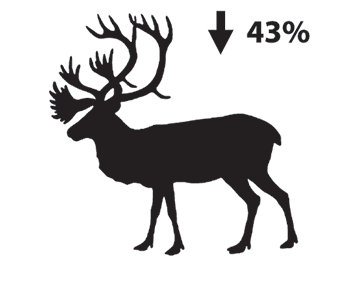

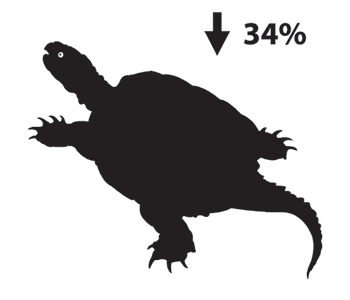

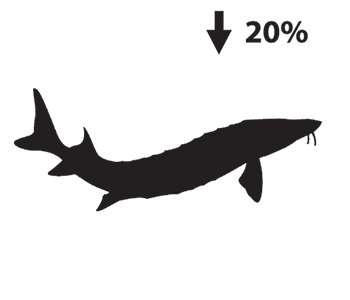

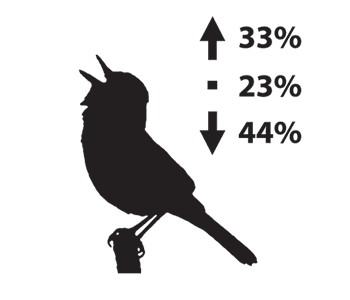

Exhibit 3.1—Species populations declined in Canada over three decades

Mammal populations declined 43% on average between 1970 and 2014Note 1

Amphibian and reptile populations declined 34% on average between 1970 and 2014Note 1

Fish populations declined 20% on average between 1970 and 2014Note 1

On average, for all bird species that could be monitored, 44% declined, 33% increased, and 23% showed little overall change between 1970 and 2010Note 2

3.9 Some declines in plant and animal species can be attributed to declines in the ecosystems that are important habitats for the species (Exhibit 3.2).

Exhibit 3.2—Some ecosystems vital to plants and animals in Canada have declined significantly

Wetlands In general, wetlands have declined because the land has been converted for agriculture or other development. Wetlands near urban areas are particularly threatened, with 80% to 90% of original wetlands converted to other uses in or near Canada’s large urban centres.Note 1 Photo: © Environment Canada |

Grasslands Native grasslands have been reduced to a fraction of their original size. Although the declines are slowing, they continue in some areas in the Prairies.Note 1 Grasslands are an important habitat for many species, including species at risk.Note 1 For example, since 1970, grassland birds have declined by about 70%. Note 2, Note 3 Photo: © Parks Canada / Max Finkelstein |

Deciduous Carolinian forests The deciduous Carolinian forests of southwestern Ontario support a greater variety of wildlife than any other ecosystem in the country. This variety includes 40% of Canada’s breeding birds. An estimated 40% of Canada’s species at risk, including birds, live in this zone. More than 90% of the land has been transformed by forestry, agriculture, and urbanization. Less than 5% of the original woodland remains. Note 4, Note 5 Photo: © Nature Conservancy of Canada |

3.10 As Canada’s National Focal Point for the Convention on Biological Diversity, Environment and Climate Change Canada has the role of coordinating the efforts of federal government departments, provinces and territories, and others to implement the Convention. The Department also liaises with the Convention Secretariat and other parties to the Convention and represents Canada at international meetings.

3.11 The Government of Canada is responsible for protecting, conserving, and recovering the biodiversity of oceans, lands, and waters under its jurisdiction. This responsibility includes protecting and preserving aquatic species, migratory birds, and federally listed species at risk. The federal government must engage with provinces and territories because they have jurisdiction over many lands and waters within their boundaries.

3.12 Many federal departments and agencies have specific responsibilities related to Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets.

3.13 In 1998, 2000, 2005, and 2013, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development audited the Government of Canada’s work related to biodiversity. The following reports contain the results of these audits and note the lack of a plan to achieve Canada’s goals:

- 1998 May Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 4—Canada’s Biodiversity Clock Is Ticking;

- 2000 May Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 9—Follow-Up of Previous Audits: More Action Needed;

- 2005 September Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 3—Canadian Biodiversity Strategy: A Follow-Up Audit; and

- 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting the Goals of the International Convention on Biological Diversity.

3.14 In the 2013 report, we expressed our concern that without clear planning, Canadians would not know how Environment and Climate Change Canada intended to lead Canada’s response to the Convention.

3.15 The Commissioner also reported on audits of specific aspects of biodiversity, including species at risk and federal protected areas, in 2001, 2008, and 2013. The following reports contain the results of these audits:

- 2001 October Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 1—A Legacy Worth Protecting: Charting a Sustainable Course in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River Basin;

- 2008 March Status Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 4—Ecosystems—Federal Protected Areas for Wildlife;

- 2008 March Status Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 5—Ecosystems—Protection of Species at Risk;

- 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 4—Protected Areas for Wildlife; and

- 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 6—Recovery Planning for Species at Risk.

Focus of the audit

3.16 This audit focused on whether Environment and Climate Change Canada provided national leadership and coordination to conserve Canada’s biodiversity. It also examined whether responsible federal departments and agencies were working to meet selected biodiversity conservation targets.

3.17 The federal departments and agencies included in the audit were

- Environment and Climate Change Canada,

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada,

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada,

- Parks Canada, and

- Statistics Canada.

3.18 This audit is important because biodiversity underpins the functioning of the ecosystems on which we depend for food and fresh water, health and recreation, and protection from natural disasters. Biodiversity is at risk nationally and globally. In recognition of the urgent need for action to support biodiversity, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2011–2020 as the United Nations Decade on Biodiversity.

3.19 More details about the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

National leadership

Overall message

3.20 Overall, we found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not provide effective leadership and did not effectively coordinate the actions required to achieve Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets. The Department focused its leadership efforts on broad administrative activities, such as representing Canada at international meetings, creating national committees, and coordinating national reports. The Department worked with federal, provincial, and territorial partners to identify specific actions and initiatives that could support Canada’s biodiversity targets but did not analyze whether these actions and initiatives would be sufficient to achieve the targets. Furthermore, the Department did not compile comprehensive information to report on performance and progress toward the 2020 biodiversity targets.

3.21 These findings matter because without strong national leadership, Canada’s actions may not be effective in meeting the country’s targets by 2020. An integrated national approach ensures that actions to conserve biodiversity are coordinated across the country, that progress is tracked, and that any required corrections or improvements can be identified and implemented in time to achieve the biodiversity targets by 2020.

3.22 In previous audits, we found that the Government of Canada had no plan to implement the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy developed in 1995. Our findings can be found in the following reports:

- 1998 May Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 4—Canada’s Biodiversity Clock Is Ticking;

- 2000 May Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 9—Follow-Up of Previous Audits: More Action Needed; and

- 2005 September Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 3—Canadian Biodiversity Strategy: A Follow-Up Audit.

3.23 In our 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting the Goals of the International Convention on Biological Diversity, we stated that it was not clear how Canada would achieve its proposed 2020 targets. We found that Environment Canada (currently Environment and Climate Change Canada) did not have a clear definition of, or a concrete plan for, what it wanted to achieve as Canada’s National Focal Point for the Convention on Biological Diversity.

3.24 National leadership and coordination is necessary because federal, provincial, and territorial governments share responsibility for conserving biodiversity and ensuring the sustainable use of biological resources. In addition, many different stakeholders must be engaged, including

- private property owners;

- businesses;

- First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities;

- conservation organizations;

- municipalities; and

- research institutions and foundations.

It is important that all contributors understand what they are expected to do to meet Canada’s biodiversity commitments.

3.25 Canada’s 2016–2019 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy included targets that supported the conservation and protection of biodiversity. Following its study of the Federal Sustainable Development Act, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development stated that a government-wide coordinated approach is needed for Canada’s sustainable development efforts.

3.26 In 2015, 193 United Nations member states, including Canada, unanimously adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The 2030 Agenda contains 17 goals to achieve social, economic, and environmental sustainable development worldwide. According to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, biodiversity and ecosystems are essential considerations as countries implement the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. In total, 14 of the 19 biodiversity targets relate to targets for the sustainable development goals.

Environment and Climate Change Canada did not provide effective leadership and did not effectively coordinate the actions required to achieve Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets

3.27 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not provide effective leadership and did not effectively coordinate the actions required to achieve Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets. The Department narrowly defined its role as Canada’s National Focal Point for the Convention on Biological Diversity. We also found that the Department had no plan for achieving Canada’s biodiversity targets.

3.28 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

3.29 This finding matters because without effective leadership and coordination, Canada’s ability to achieve the national biodiversity targets is at risk.

3.30 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.41.

3.31 What we examined. We examined whether Environment and Climate Change Canada led and coordinated actions in support of achieving Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets. This examination work followed up on recommendations from the 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting the Goals of the International Convention on Biological Diversity.

3.32 Our observations in this section apply to the Department’s activities for all 19 targets.

3.33 National leadership. In the 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting the Goals of the International Convention on Biological Diversity, we recommended that the Department define its priorities as the National Focal Point and develop a concrete plan for what it wanted to achieve. The Department agreed and responded that it would identify its priorities as National Focal Point along with a plan to achieve them.

3.34 We found that the Department narrowly defined its role as Canada’s National Focal Point. In this role, the Department’s priorities and efforts concentrated on

- fulfilling responsibilities to the international Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (attending meetings, responding to requests, and providing financial support);

- organizing the federal, provincial, and territorial committees on biodiversity;

- coordinating the national reports; and

- maintaining the biodivcanada.ca website.

3.35 The Department’s priorities and efforts as National Focal Point did not include working with federal, provincial, and territorial partners to identify specific actions and initiatives required to achieve Canada’s biodiversity targets.

3.36 We found that the Department did not establish an overall plan to meet Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets. The Department emphasized that the targets were not firm commitments, but rather aspirational objectives that were intended to encourage and promote collective action. Past audits also found that the Department had not established plans for previous biodiversity goals or strategies.

3.37 We also found that the Department did not define the actions and initiatives needed to achieve the targets. The Department compiled a list of actions and initiatives under way from all levels of government and from non-governmental organizations. However, we found that the Department did not analyze how these initiatives would help achieve the targets or whether they would be sufficient to do so. Department officials told us that, in 2018, they planned to assess whether these actions and initiatives were adequate. In our view, this did not leave much time to make adjustments to meet the targets.

3.38 In 2013, we recommended that the Department define milestones to help ensure Canada was on track to meet its 2020 targets. We found that the Department did not establish milestones to assess progress toward 12 of the 19 national biodiversity targets. It did, however, set short-term milestones for the other 7 biodiversity targets in the 2016–2019 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy.

3.39 In our view, the lack of a national plan left the federal, provincial, and territorial organizations and stakeholders responsible for conserving biodiversity without essential information to identify, direct, and coordinate their efforts.

3.40 Committee leadership. We found that the Department organized various committees, including interdepartmental committees, and federal, provincial, and territorial committees. These committees met regularly but only focused on 5 of the 19 targets (protected areas, species at risk, climate change impacts, alien invasive species, and biodiversity science). Department officials told us that they focused on these targets first because the targets required a high degree of collaboration and senior management engagement. Officials also told us that other mechanisms existed to support collaboration with partners on some of the other targets. We did not examine the effectiveness of these other mechanisms.

3.41 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should work with other responsible federal departments and agencies to establish the federal government’s priorities, actions, and milestones to achieve Canada’s national biodiversity targets.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will work with other responsible federal departments and agencies to identify relevant actions and milestones to support further progress toward Canada’s national biodiversity targets.

Environment and Climate Change Canada notes that achieving these targets in Canada requires action and support from across all levels of government and from Indigenous people, municipalities, businesses, the scientific community, non-governmental organizations, and individual Canadians.

Environment and Climate Change Canada did not compile comprehensive information to report on performance and progress toward the 2020 biodiversity targets

3.42 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not provide timely and meaningful comprehensive information on Canada’s progress toward the national biodiversity targets. Canada’s most recent comprehensive report to the Convention on Biological Diversity was in 2014, before the country’s national targets and indicatorsDefinition iii were finalized. Since 2014, the Department has compiled some reports that focused on specific targets, including species at risk and protected areas. We found, however, that the Department did not compile any comprehensive reports to assess progress or identify where adjustments might be needed to reach Canada’s 2020 targets.

3.43 Canada will provide its next comprehensive national report to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2018. In our view, it will be difficult to correct problems identified in 2018 before the 2020 deadline.

3.44 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Canada’s 5th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

- Biodiversity website

- Other reporting

3.45 This finding matters because transparent, regular, and current monitoring and reporting on progress helps parliamentarians and Canadians understand whether Canada is meeting its biodiversity commitments. Progress reports also help stakeholders and contributors adjust their activities or approaches to improve results.

3.46 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.54.

3.47 What we examined. Two reporting mechanisms are required under the Convention on Biological Diversity—a national progress report about every four years and a national website. We examined the Department’s reporting on Canada’s progress on biodiversity conservation through Canada’s 5th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity and the biodivcanada.ca website. We also examined reporting on indicators that was published elsewhere, such as departmental reports.

3.48 Canada’s 5th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Canada last reported to the Convention Secretariat in 2014, before finalizing national biodiversity targets and indicators. As a result, the 2014 report did not use some of the indicators that were finalized in 2015 to identify progress toward Canada’s national targets. However, we found that the report included other useful information, such as quantitative and qualitative results for, and case studies of, certain conservation activities.

3.49 As there was no further reporting to the Convention after 2014, progress toward several national targets was never reported internationally. Canada’s next report to the Convention on Biological Diversity is expected at the end of 2018. In our view, it will be difficult to make corrections or improvements before 2020.

3.50 Biodiversity website. The Department’s other main reporting mechanism is the biodivcanada.ca website. It provides public access to information from the federal, provincial, and territorial working group on biodiversity, including news, events, and general biodiversity information.

3.51 Following the 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting the Goals of the International Convention on Biological Diversity, Environment and Climate Change Canada developed an action plan that included a commitment to adding information to this website. We found that the website was not updated regularly. We noted, however, that the Department added links to data for some of the indicators in November 2017.

3.52 Other reporting. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not compile the comprehensive information and data needed to assess progress toward Canada’s 2020 biodiversity goals and targets since they were announced in 2015.

3.53 However, we found that some information on specific targets was updated regularly in publicly available sources, such as departmental reports and the Government of Canada’s website on environmental sustainability indicators. These sources provided information about progress on priorities, including species at risk and protected areas. However, data on other targets was never publicly reported or was outdated. For example, an Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada report published in 2016 contained agricultural information—related to the 2020 biodiversity target for agricultural lands (target 7)—that was based on 2011 data. We found that data collected in 2016 was not published.

3.54 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should regularly compile current and comprehensive information on Canada’s performance and progress toward the 2020 biodiversity targets and make that information publicly available in one accessible location.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will compile information on the progress toward the 2020 biodiversity targets and make it publicly available through public reporting and regular website updates.

Progress and results

Overall message

3.55 Overall, we found uneven progress by the five audited federal departments and agencies in their efforts to meet the six 2020 biodiversity targets we examined. We found that the federal organizations met, or would meet by 2020, the two targets on collecting adequate and relevant information about biodiversity and ecosystem services. We also found that the federal organizations made progress toward two targets pertaining to planning and managing lands and waters, but they were unlikely to fully meet these targets by the 2020 deadline. Lastly, we found that the federal organizations were not working to meet the targets intended to reduce pressures and cumulative effects on biodiversity and promote sustainability in the production and consumption of Canada’s biological resources.

3.56 These findings matter because much of Canada’s biodiversity is in decline and needs urgent attention. In our view, the work and efforts of the federal organizations we audited will not be sufficient to reverse this decline.

3.57 Exhibit 3.3 shows the indicators for each of the six targets examined in this audit.

Exhibit 3.3—Performance indicators were established for the six national biodiversity targets examined

Goal A: Planning and managing lands and waters using an ecosystem approach

| Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Target 1 By 2020, at least 17% of terrestrial areas and inland water, and 10% of coastal and marine areas, are conserved through networks of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. |

|

|

Target 2 By 2020, species that are secure remain secure, and populations of species at risk listed under federal law exhibit trends that are consistent with recovery strategies and management plans. |

|

Goal B: Reducing pressures and cumulative effects on biodiversity and promoting sustainability in the production and consumption of Canada’s biological resources

| Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Target 7 By 2020, agricultural working landscapes provide a stable or improved level of biodiversity and habitat capacity. |

|

|

Target 10 By 2020, pollution levels in Canadian waters, including pollution from excess nutrients, are reduced or maintained at levels that support healthy aquatic ecosystems. |

|

Goal C: Collecting adequate and relevant information about biodiversity and ecosystem services

| Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Target 16 By 2020, Canada has a comprehensive inventory of protected spaces that includes private conservation areas. |

|

|

Target 17 By 2020, measures of natural capitalnote * related to biodiversity and ecosystem services are developed on a national scale, and progress is made in integrating them into Canada’s national statistical system. |

|

Source: Adapted from 2020 Biodiversity Goals and Targets for Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2015

3.58 The Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 report, published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, stated that the best way to protect biodiversity is to ensure that it is a significant factor in decision making across

- sectors, departments, and economic activities;

- land use planning systems;

- spatial planning for freshwater and sea areas; and

- policies to reduce poverty and adapt to climate change.

The report added that this approach, referred to as mainstreaming, was being used in some countries in relation to climate change. In our view, federal departments and agencies can support mainstreaming by consistently applying the Cabinet Directive on Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. This Cabinet directive requires federal departments and agencies to consider environmental concerns early in the planning of policy, plan, and program proposals.

The five audited federal departments and agencies made uneven progress in their efforts to meet the six 2020 biodiversity targets we examined

3.59 We found that the five federal departments and agencies we audited met, or would meet by 2020, the targets for protected areas inventory (target 16) and natural capitalDefinition iv (target 17). We also found that they made progress toward the targets for protected areas (target 1) and species at risk (target 2), but that they were unlikely to fully meet these targets by the 2020 deadline. Lastly, we found that they were not working to meet the targets for agricultural lands (target 7) and water pollution (target 10).

3.60 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Results for target 1 (protected areas)

- Results for target 2 (species at risk)

- Results for target 7 (agricultural lands)

- Results for target 10 (water pollution)

- Results for target 16 (protected areas inventory)

- Results for target 17 (natural capital)

3.61 This finding matters because Canada set national targets for biodiversity conservation to be achieved by 2020. It is also important for Canada to protect its lands and waters and address the pressures on our national biodiversity to maintain the economic and social benefits Canadians derive from natural resources and ecosystems.

3.62 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.87.

3.63 What we examined. We examined the latest available results for the six targets selected for this audit. Our goal was to determine whether responsible federal departments and agencies were working to meet these targets by 2020. We also examined whether the selected departments and agencies had plans in place for each target and established initiatives that could contribute to meeting the targets.

3.64 Results for target 1 (protected areas). Target 1 consisted of two components:

- coastal and marine areas, and

- terrestrial and inland waters.

We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada were working to meet both components. They informed us that they were determined to meet the targets for both components under target 1 by 2020 (Exhibit 3.4).

Exhibit 3.4—Responsible federal departments and agencies were unlikely to fully meet the biodiversity target for protected areas (target 1)

3.65 Fisheries and Oceans Canada is responsible for leading efforts to protect coastal and marine areas. The Prime Minister mandated the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard to increase the proportion of Canada’s marine and coastal protected areas to 5% by 2017 and 10% by 2020. In June 2016, the Department launched a five-point plan to achieve these targets. We found that the Department had met the milestones under this plan.

3.66 On the basis of progress made at the time of this audit, we found that the Government of Canada would likely meet the coastal and marine component of target 1 by 2020. We noted that the government established new marine protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, such as marine refugesDefinition v. With respect to the Tallurutiup Imanga area, located in Lancaster Sound in Nunavut, Parks Canada expected that it would receive an official designation as a national marine conservation area, a specific type of protected area, upon the completion of an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement in March 2019.

3.67 For each marine protected area proposed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Department told us that it undertook a risk assessment to determine how human activities might affect conservation objectives. The Department also told us that it used these risk assessments, along with other studies and consultations, to identify whether activities, such as oil and gas exploration, should be allowed or prohibited.

3.68 The target for protecting Canada’s terrestrial areas and inland waters was 17% by 2020. At the end of 2016, only 10.5% was protected. To reach the 2020 target, Canada must increase the extent of its protected areas by 6.5%.

3.69 The majority of Canada’s terrestrial lands and inland waters are managed by non-federal entities, including provincial and territorial governments. We found that the Government of Canada developed a new management approach in 2017, called the Pathway to Canada Target 1, to coordinate and encourage protected area efforts (Exhibit 3.5).

Exhibit 3.5—The Government of Canada launched a new management approach to improve quantitative and qualitative results for land and water protection in Canada

Floral display in a meadow of the upper subalpine zone, Mount Revelstoke National Park.

Photo: © Parks Canada / R.D. Muir

In February 2017, the Government of Canada launched the Pathway to Canada Target 1 initiative to coordinate and encourage efforts by all relevant partners. The initiative focused on creating new conditions to improve both quantitative and qualitative results for land and water protection. Examples of qualitative elements include the effectiveness of management within parks and connected areas between parks.

At the time of this audit, the initiative

- was being co-led by Parks Canada and Alberta Parks;

- was being guided by a national steering committee;

- involved all relevant federal, provincial, and territorial departments and agencies;

- included a national advisory panel and an Indigenous circle of experts to provide Indigenous perspectives; and

- had expert groups to address the quality of protection within established protected areas.

3.70 On the basis of the progress made at the time of this audit, we found that, without the full implementation of commitments, new funding and tools, and the collaboration that could be achieved through the Pathway to Canada Target 1 initiative, Canada would be unlikely to meet the target of 17% for protecting Canada’s terrestrial areas and inland waters by 2020.

3.71 In 2015, the Prime Minister mandated the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change to manage and expand national wildlife areas and migratory bird sanctuaries, which include marine and terrestrial protected areas. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not create any new national wildlife areas or migratory bird sanctuaries since 2010. We also found that the Department did not assess whether any of the current national wildlife areas and migratory bird sanctuaries should be delisted because they no longer met the criteria for protected areas.

3.72 In 2016, Environment and Climate Change Canada evaluated 80% of its protected areas using a tool developed by the World Commission on Protected Areas. The Department found that only 10% of these areas had adequate management, and there were significant deficiencies because of insufficient resources and personnel. The Department’s evaluation concluded that it was difficult to estimate whether Canadians were benefiting from the investment in protected areas.

3.73 Results for target 2 (species at risk). Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada stated that it was too early to determine whether the species at risk target would be met. Recovery strategies and management plans have recovery objectives for each species at risk. These objectives can involve keeping a species stable, stopping the decline of a species, or improving populations of at-risk species.

3.74 We found that results did not improve, despite actions taken between 2014 and 2016. We found that, in 2014, the objectives set out in the recovery strategies and management plans were not met for 32% of species at risk (or 30 out of 94 species). We found that, in 2016, the objectives set out in the recovery strategies and management plans were not met for 37% of species at risk (or 46 out of 123 species). Environment and Climate Change Canada noted that it takes time to recover species at risk and that two years was not enough time to demonstrate that recovery actions were working for the vast majority of species.

3.75 To meet the species at risk target, recovery strategies and management plans must be in place for all the species listed under the Species at Risk Act. In their responses to the 2013 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 6—Recovery Planning for Species at Risk, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Parks Canada, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada agreed to complete the outstanding recovery strategies and management plans. The 2016–2019 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy set a target for the Government of Canada to eliminate the backlog of outstanding recovery strategies and management plans by 2018.

3.76 We found that the three organizations developed recovery strategies and management plans for 95% of species at risk where legislated timelines for completion had been reached. We found that Parks Canada completed all of its required recovery strategies and management plans. At the time of our audit, we found that Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not complete overdue recovery strategies and management plans for 25 species.

3.77 After developing recovery strategies and management plans, federal departments and agencies are required by the Species at Risk Act to provide progress reports every five years on recovery efforts to improve the status of each species. We found the following:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada provided 1 of its 143 required progress reports. More than one third of these progress reports were more than four years late.

- Parks Canada provided 1 of its required 7 progress reports, and 2 of these reports were more than four years late.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada completed 45 of 68 required progress reports. We also found that the Department used some of its completed reports to update information on the population of species at risk. The remaining 23 progress reports were, on average, one year overdue.

3.78 We found that delays in planning for the recovery of species can affect the implementation of recovery efforts (Exhibit 3.6).

Exhibit 3.6—Delays in implementing the Species at Risk Act increased threats to the boreal woodland caribou

Caribou at Ramah Bay in Torngat Mountains National Park.

Photo: © Parks Canada / H. Wittenborn

Canada is home to 51 herds of the boreal woodland caribou, whose habitat extends across nine provinces and territories, from Newfoundland and Labrador to Yukon, on both federal and non-federal lands. In 2014, 37 out of 51 caribou herds were identified as declining. The main reasons for the decline were increased numbers of predators and habitat loss resulting from fires and natural resource extraction. In 2017, Environment and Climate Change Canada stated that the species was continuing to decline.

Recognizing that urgent conservation efforts were needed to save the woodland caribou from becoming extinct, Canada listed it as a threatened species in 2003. However, there have been many delays in implementing the Species at Risk Act for this species. Here are some examples:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada did not develop a recovery strategy for the species until 2012, five years later than required.

- The Department did not report on steps taken to protect critical habitat, although it was required to do so every 180 days following the development of the recovery strategy. In 2017, the Department committed to reporting on steps taken to protect critical habitat by April 2018.

- The Department was scheduled to release an action plan for recovery measures in 2015. It released a proposed action plan in 2017, but the plan was not finalized at the time of this audit.

- The Department did not receive range plans from the provinces and territories. The Department still needs to assess these plans and report on steps taken to protect critical habitat.

- The Department met the October 2017 deadline for reporting on progress to implement the recovery strategy.

Parks Canada provided legal protection to some caribou habitat that it administered, but the protection covers only a small fraction of the caribou habitat. Provinces and territories are responsible for managing lands, natural resources, and wildlife within the boreal woodland caribou’s habitat.

Planning for the recovery of this species took more than a decade. Implementing recovery actions and assessing and reporting on steps taken to protect critical habitat are the next important steps for Environment and Climate Change Canada.

3.79 Results for target 7 (agricultural lands). We found that Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada was not working to meet target 7, which is related to ensuring that agricultural working landscapes provide a stable or improved level of biodiversity and habitat capacity.

3.80 Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada reported that wildlife habitat capacity of 85% of farmland remained stable between 1996 and 2011. We noted, however, that most of the farmlands in Canada had a low to very low capacity to support wildlife habitat (Exhibit 3.7). We found that wildlife habitat capacity declined on farmland by 10% against the national indicator during that same period. This can be largely attributed to a decline in the ability of farmlands from Windsor, Ontario, to Québec City, Quebec, to support wildlife. In our view, the target will not be met unless the declining trends change.

Exhibit 3.7—Wildlife habitat capacity on farmlands declined by 10% between 1996 and 2011

Source: Adapted from Environmental Sustainability of Canadian Agriculture: Agri-Environmental Indicator Report Series—Report #4, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 2016

Exhibit 3.7—text version

This bar chart shows changes in the levels of wildlife habitat capacity of Canadian farmland from 1996 to 2011. In general, wildlife habitat capacity on farmlands declined by 10 percent over this time period. In particular,

- the percentage of farmland having a very low wildlife habitat capacity increased,

- the percentage of farmland having low to high wildlife capacity decreased, and

- the percentage of farmland having very high wildlife capacity stayed almost the same (a slight increase).

The following table lists the wildlife habitat capacity on farmland in 1996, 2001, 2006, and 2011.

| Level of wildlife habitat capacity | Percentage of farmland | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 | |

| Very high | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| High | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| Moderate | 7.6 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 4.5 |

| Low | 53.2 | 50.4 | 50.9 | 46.1 |

| Very low | 37.3 | 41.0 | 42.2 | 47.9 |

Source: Adapted from Environmental Sustainability of Canadian Agriculture: Agri-Environmental Indicator Report Series—Report #4, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 2016

3.81 Results for target 10 (water pollution). We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada was not working to meet target 10. According to the Department, target 10 will be supported by work outlined in the Pristine Lakes and Rivers chapter of Canada’s 2016–2019 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy.

3.82 We found that it was not clear how progress toward target 10 by 2020 would be supported by the federal strategy. For example, the first indicator for target 10 is to reduce phosphorus levels in the Great Lakes. The federal strategy initially set a target for reducing phosphorus in Lake Erie by 2025, but this deadline was later removed from the strategy.

3.83 Results for target 16 (protected areas inventory). We found that the Government of Canada was likely to meet target 16. In this regard, we found that Environment and Climate Change Canada prepared an inventory of protected spaces, and federal departments and agencies were working on new definitions and criteria for adding other types of protected areas to the inventory.

3.84 Results for target 17 (natural capital). We found that Statistics Canada met target 17. We found that the agency published new national-scale data and maps related to biodiversity and ecosystem services, usually on an annual basis, on different environmental topics. We noted, however, that the indicators developed for this target were not specific, as they did not indicate how much change was required to meet the target (see paragraph 3.97).

3.85 We found that Statistics Canada’s efforts to measure natural capital and ecosystem services were largely driven by departmental priorities and not the 2020 target. In 2012, Statistics Canada developed a framework, based on the concept of natural capital, to identify aspects of the environment that should be measured, together with how the data should be collected and organized. In 2013, Statistics Canada published the results of a two-year research project with six other federal departments and agencies that measured some of Canada’s ecosystem goods and services.

3.86 At the time of this audit, Statistics Canada was working on a proposal for a census of the environment, which would

- compile and integrate environmental data to measure ecosystems,

- quantify the services they provide, and

- evaluate the benefits to people.

In our view, this census could provide consistent information to Canadians on the value of our ecosystems.

3.87 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada should identify the improvements and adjustments needed to achieve the 2020 biodiversity targets for which they are responsible.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. When it is the federal lead agency responsible for a target, Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with other federal departments and agencies as appropriate, will identify the additional actions needed to make further progress toward Canada’s 2020 biodiversity goals and targets.

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Now that it has established a partnership framework and received draft recommendations through the Pathway to Canada Target 1 initiative, Parks Canada and other federal partner departments are in a position to continue federal leadership to the 2020 target and beyond. This will include working with the provinces and territories to develop a pan-Canadian plan that specifies a governance structure, as well as new conservation tools and a collective accounting framework to report on quantitative and qualitative aspects of target 1 (protected areas).

For target 2 (species at risk), Parks Canada will continue its ecosystem approach to protect species listed under the Species at Risk Act and other species of conservation concern through multi-species action planning. Given its ecological integrity mandate in the management of national parks, Parks Canada believes that the ecosystem-based approach is the most efficient and effective way to achieve recovery objectives and progress reporting. Parks Canada will continue to develop and share approaches for the recovery of species at risk with other land managers and partners.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. As the lead department for Canada’s marine protected area (MPA) network, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to work with federal partners to identify opportunities to improve interdepartmental coordination and collaboration on the development and management of MPAs for target 1 (protected areas). To formalize relationships, terms of reference will be established for the Federal Interdepartmental MPA Strategy Director General’s Committee, the Directors General Interdepartmental Committee on Oceans, and the Assistant Deputy Ministers Interdepartmental Committee on Oceans. The implementation date will be 31 March 2018.

Under Environment and Climate Change Canada’s lead, Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s contribution toward meeting target 2 (species at risk) will focus on aquatic species. To improve the percentage of listed aquatic species that show improvement when reported under the Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators program, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to address any backlogs of outstanding recovery strategies and management plans, as well as action plans and critical habitat orders, for aquatic species listed under the Species at Risk Act. It will also focus on the implementation of recovery actions. The implementation date will be according to Environment and Climate Change Canada’s lead.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Achieving the target on largely privately owned agricultural lands in Canada is a shared responsibility of multiple departments, ministries, and levels of government, in collaboration with non-governmental organizations and private landowners. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s contribution toward the 2020 biodiversity target will be as follows:

- Lead the development, improvement, and reporting of the target 7 (agricultural lands) indicators, in collaboration with Environment and Climate Change Canada and the provinces. Complete negotiations and sign the Canadian Agricultural Partnership (CAP), a joint federal-provincial-territorial agreement for 2018–2023, which identifies biodiversity as an environmental priority. Report on the list of practices eligible for funding under the CAP that support on-farm biodiversity. The due date will be December 2018.

- Report on Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s biodiversity-related science projects funded under the CAP and the new investment of $70 million over six years to further support agricultural science and innovation. Develop a summary of government and non-government funded projects that support on-farm biodiversity. Hold, at minimum, one annual meeting of federal-provincial-territorial agriculture ministries to discuss ways of improving biodiversity-related issues on farmland. The due date will be March 2019.

There were limitations with the performance indicators used to track progress toward Canada’s biodiversity targets

3.88 We found that some of the indicators Environment and Climate Change Canada used to monitor, track, and report on performance and progress did not provide a clear picture of whether Canada was effective at conserving biodiversity. We found cases where indicators were not specific, did not measure quality of progress made, or did not include enough information to accurately measure progress.

3.89 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

3.90 This finding matters because clear and specific information is needed to monitor, track, and report on Canada’s performance and progress toward its 2020 national biodiversity targets. To measure progress, federal departments and agencies use performance indicators. If the indicators have limitations, results may be misleading.

3.91 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.101.

3.92 What we examined. We examined all indicators for each of the six targets we selected in Exhibit 3.3. Our goal was to determine whether these performance indicators provided effective and relevant measures for federal departments and agencies to track progress toward the biodiversity targets.

3.93 Quality of national biodiversity indicators. Indicators are used to provide information to monitor, track, and report on performance and progress toward Canada’s biodiversity targets. We found that there were indicators to support each of the targets, but some of the indicators had limitations. As a result, it was not clear that progress measured by the indicators would actually reflect the conservation of biodiversity.

3.94 Environment and Climate Change Canada worked with federal departments and agencies, provinces, territories, and Indigenous organizations to choose indicators to help measure the progress toward the 19 targets. Department officials told us that most of the current indicators were chosen from sources that existed before the national biodiversity targets and indicators were finalized in 2015. In 2013, the Department held consultations with stakeholders working on biodiversity. Despite feedback from stakeholders that identified limitations with the indicators and potential improvements, we found that the Department made minimal changes to the indicators.

3.95 For example, target 7 (agricultural lands) aims to ensure that agricultural working landscapes provide a stable or improved level of biodiversity and wildlife habitat capacity. Stakeholders noted that the proposed indicators under this target were unclear and suggested including an indicator on pollination, as it was a key issue. However, we found that the Department made no changes despite the recommendation to do so. According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, adding a pollinator indicator was not feasible because there is a lack of comprehensive data available on pollinators.

3.96 We also found that targets for protected areas, agricultural lands, and water pollution (targets 1, 7, and 10, respectively) did not include many of the indicators suggested by the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. For example, the Aichi targets suggested an indicator related to connecting different protected areas, but Canada did not include this indicator.

3.97 We found that the indicators for some targets were not specific. For example, we found that the indicators for target 17 (natural capital) did not specify how much change was required to achieve the target. Federal departments noted this limitation in 2012, observing that the indicators did not define what Statistics Canada should be working toward. Nonetheless, we found that no changes were made.

3.98 Some indicators failed to address quality. Here are two examples:

- For target 1 (protected areas), Environment and Climate Change Canada acknowledged that the indicators focused solely on the amount and proportion of what was protected, not the quality of protection.

- For target 7 (agricultural lands), Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada acknowledged that one indicator (the number of environmental farm plans) could not be used to assess environmental performance or conservation of biodiversity (Exhibit 3.8).

Exhibit 3.8—Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada did not assess the effect of environmental farm plans on biodiversity conservation

Since 2003, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada has participated in cost-sharing programs with the provinces and territories to provide funds to farmers who develop environmental farm plans. An environmental farm plan is a voluntary self-assessment tool for farmers to identify the agri-environmental risks and benefits associated with their farming operations and to establish ways to mitigate these risks. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada reported that farmers with an environmental farm plan were more likely to adopt management practices that benefit the environment.

Although the Department collected data on the number of environmental farm plans produced, we found that it did not know what effect the plans were having on the environment or on biodiversity conservation. In fact, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada reported that wildlife habitat quality had declined on farmland since 1996.

3.99 We found that some performance indicators were too narrow in scope to be effective. For example, for target 10 (water pollution), we found that two of four indicators focused on only one pollutant (phosphorus) in two regions in Canada (the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River). For the other two indicators (which were intended to cover the entire country), we found that

- the North was under-represented;

- not all water quality issues were included; and

- data was gathered only for fresh water, not ocean water.

3.100 Work to develop new national indicators. We found that federal departments and agencies were working to develop new qualitative indicators for target 1 (protected areas), through the Pathway to Canada Target 1 initiative.

3.101 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada, in collaboration with other responsible federal departments and agencies, should review the indicators used to measure performance and progress toward Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets to determine whether they are effective. It should also implement improvements where necessary.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will continue to work with responsible departments and agencies to review the indicators used to measure performance and progress toward Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets. It will make improvements to existing national indicators where appropriate.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada will continue to work with Environment and Climate Change Canada to review and improve, where possible, the current indicator (the wildlife habitat capacity indicator) and explore the use of additional indicators that may better reflect on-farm action and specific biodiversity issues.

Statistics Canada’s response. Agreed. Statistics Canada will continue to work with Environment and Climate Change Canada to review and improve the current indicators (natural capital) to make them more useful and specific.

Conclusion

3.102 We concluded that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not provide effective national leadership and coordination of actions required to meet the 2020 targets to conserve Canada’s biodiversity.

3.103 We also concluded that the five audited departments and agencies made uneven progress in their efforts to meet the six 2020 biodiversity targets we examined.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on Environment and Climate Change Canada’s national leadership and coordination, and the progress by selected federal departments and agencies in working to meet selected Canadian biodiversity targets. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the work by Environment and Climate Change Canada and selected federal departments and agencies in relation to Canada’s biodiversity targets complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Environment and Climate Change Canada provided national leadership and coordination and whether responsible federal departments and agencies were working to meet selected targets to conserve Canada’s biodiversity for present and future generations.

Scope and approach

The following departments and agencies were included in the scope of the audit:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada,

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada,

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada,

- Parks Canada, and

- Statistics Canada.

For this audit, we selected six targets that had a clear federal responsibility. We also considered recently completed audits and potential future audits.

The audit team interviewed responsible officials, analyzed documents and information sources, and examined systems and processes.

Criteria

To determine whether Environment and Climate Change Canada provided national leadership and coordination to conserve Canada’s biodiversity for present and future generations, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with others, prepared an action plan that describes how the federal, provincial, and territorial partners will support the achievement of the 2020 biodiversity goals and targets for Canada. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada coordinated actions with other federal, provincial, and territorial partners in support of achieving the 2020 biodiversity goals and targets. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada coordinated reporting on progress toward the 2020 biodiversity goals and targets. |

|

To determine whether responsible federal departments and agencies were working to meet selected targets to conserve Canada’s biodiversity for present and future generations, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Selected departments and agenciesNote * defined roles and responsibilities related to the selected targets. |

|

|

Selected departments and agenciesNote * identified and implemented actions that make progress toward selected targets. |

|

|

Selected departments and agenciesNote * identified valid and reliable indicators to measure progress toward achieving the selected targets. |

|

|

Selected departments and agenciesNote * assessed and reported on progress toward achieving the selected targets. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between May 2013 and December 2017. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 31 December 2017, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Andrew Hayes

Director: Marc Riopel

Paul Csagoly

Kristin Lutes

Kajal Patel

Nathan Adams

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

National leadership

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.41 Environment and Climate Change Canada should work with other responsible federal departments and agencies to establish the federal government’s priorities, actions, and milestones to achieve Canada’s national biodiversity targets. (3.31 to 3.40) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will work with other responsible federal departments and agencies to identify relevant actions and milestones to support further progress toward Canada’s national biodiversity targets. Environment and Climate Change Canada notes that achieving these targets in Canada requires action and support from across all levels of government and from Indigenous people, municipalities, businesses, the scientific community, non-governmental organizations, and individual Canadians. |

|

3.54 Environment and Climate Change Canada should regularly compile current and comprehensive information on Canada’s performance and progress toward the 2020 biodiversity targets and make that information publicly available in one accessible location. (3.47 to 3.53) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will compile information on the progress toward the 2020 biodiversity targets and make it publicly available through public reporting and regular website updates. |

Progress and results

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.87 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada should identify the improvements and adjustments needed to achieve the 2020 biodiversity targets for which they are responsible. (3.63 to 3.86) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. When it is the federal lead agency responsible for a target, Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with other federal departments and agencies as appropriate, will identify the additional actions needed to make further progress toward Canada’s 2020 biodiversity goals and targets. Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Now that it has established a partnership framework and received draft recommendations through the Pathway to Canada Target 1 initiative, Parks Canada and other federal partner departments are in a position to continue federal leadership to the 2020 target and beyond. This will include working with the provinces and territories to develop a pan-Canadian plan that specifies a governance structure, as well as new conservation tools and a collective accounting framework to report on quantitative and qualitative aspects of target 1 (protected areas). For target 2 (species at risk), Parks Canada will continue its ecosystem approach to protect species listed under the Species at Risk Act and other species of conservation concern through multi-species action planning. Given its ecological integrity mandate in the management of national parks, Parks Canada believes that the ecosystem-based approach is the most efficient and effective way to achieve recovery objectives and progress reporting. Parks Canada will continue to develop and share approaches for the recovery of species at risk with other land managers and partners. Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. As the lead department for Canada’s marine protected area (MPA) network, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to work with federal partners to identify opportunities to improve interdepartmental coordination and collaboration on the development and management of MPAs for target 1 (protected areas). To formalize relationships, terms of reference will be established for the Federal Interdepartmental MPA Strategy Director General’s Committee, the Directors General Interdepartmental Committee on Oceans, and the Assistant Deputy Ministers Interdepartmental Committee on Oceans. The implementation date will be 31 March 2018. Under Environment and Climate Change Canada’s lead, Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s contribution toward meeting target 2 (species at risk) will focus on aquatic species. To improve the percentage of listed aquatic species that show improvement when reported under the Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators program, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to address any backlogs of outstanding recovery strategies and management plans, as well as action plans and critical habitat orders, for aquatic species listed under the Species at Risk Act. It will also focus on the implementation of recovery actions. The implementation date will be according to Environment and Climate Change Canada’s lead. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Achieving the target on largely privately owned agricultural lands in Canada is a shared responsibility of multiple departments, ministries, and levels of government, in collaboration with non-governmental organizations and private landowners. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s contribution toward the 2020 biodiversity target will be as follows:

|

|

3.101 Environment and Climate Change Canada, in collaboration with other responsible federal departments and agencies, should review the indicators used to measure performance and progress toward Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets to determine whether they are effective. It should also implement improvements where necessary. (3.92 to 3.100) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will continue to work with responsible departments and agencies to review the indicators used to measure performance and progress toward Canada’s 2020 biodiversity targets. It will make improvements to existing national indicators where appropriate. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada will continue to work with Environment and Climate Change Canada to review and improve, where possible, the current indicator (the wildlife habitat capacity indicator) and explore the use of additional indicators that may better reflect on-farm action and specific biodiversity issues. Statistics Canada’s response. Agreed. Statistics Canada will continue to work with Environment and Climate Change Canada to review and improve the current indicators (natural capital) to make them more useful and specific. |