2019 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 2—Protecting Fish From Mining Effluent

2019 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 2—Protecting Fish From Mining Effluent

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Managing effects of mine waste and effluent on fish and their habitat

- Inspecting mine sites and addressing violations

- Environment and Climate Change Canada’s frequency of metal mine site inspections was significantly lower in Ontario than in other regions, and its reporting on compliance was incomplete

- Environment and Climate Change Canada inspected non-metal mines less often than metal mines

- Environment and Climate Change Canada addressed violations of regulations at both metal and non-metal mine sites

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 2.1—The Fisheries Act and its regulations form the legislative and regulatory framework for mining that affects fish

- 2.2—Mining companies use tailings impoundment areas to store harmful mining by-products

- 2.3—Environment and Climate Change Canada reviews proposals for mine waste disposal and consults with the public

- 2.4—Plans to offset loss of fish and their habitat must be assessed, authorized, and monitored

- 2.5—Regulations require mining companies to assess the effects of mining effluent on fish and their habitat

- 2.6—Between January 2013 and June 2018, Environment and Climate Change Canada inspected metal mines every 1.5 years on average, but less frequently in Ontario

- 2.7—Environment and Climate Change Canada took various types of enforcement actions to address alleged violations of regulations and legislation at mining sites from January 2013 to August 2018

Introduction

Background

2.1 The mining industry in Canada accounts for approximately $60 billion, or 3% of the national gross domestic product. Mining contributes positively to the economy, but mining activities must be carefully managed to avoid negative consequences to fish and their habitat.

2.2 In 2018, approximately 138 metal mines and 117 non-metal mines operated in Canada. Mining operations involve crushing large quantities of rock and using chemical processes to extract desired materials. This process creates mine waste, including a liquid sludge, or effluent, that may contain substances such as cyanide, zinc, and selenium, which are harmful to fish. The effluent is treated to reduce the concentrations of these substances before being released into the environment.

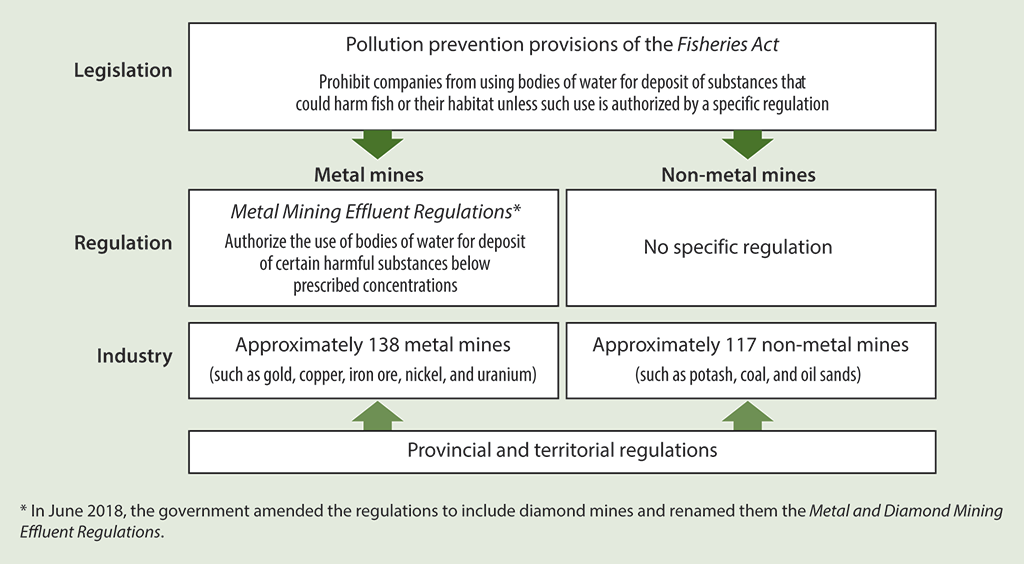

2.3 At the federal level, the Fisheries Act contains provisions to protect fisheries and prevent pollution from any source, including mining. In addition, the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations, under the Fisheries Act, allow effluent containing certain substances that can harm fish and their habitat to be deposited into bodies of water (Exhibit 2.1). The regulations also require reporting on the levels of these substances.

Exhibit 2.1—The Fisheries Act and its regulations form the legislative and regulatory framework for mining that affects fish

Source: Based on information from Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada

Exhibit 2.1—text version

This diagram outlines the legislative and regulatory framework intended to protect fish from harmful substances in metal and non-metal mining.

Legislation

The pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act cover both the metal and non-metal mining industries. The provisions prohibit companies from using bodies of water for deposit of substances that could harm fish or their habitat unless such use is authorized by a specific regulation.

Regulation

The Metal Mining Effluent Regulations authorize the use of bodies of water for deposit of certain harmful substances below prescribed concentrations, and they apply only to metal mines. In June 2018, the federal government amended the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations to include diamond mines and renamed them the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations.

Non-metal mines are not covered by a specific regulation.

Industry

The metal mining industry consists of approximately 138 mines of substances such as gold, copper, iron ore, nickel, and uranium. The non-metal mining industry consists of approximately 117 mines of substances such as potash, coal, and oil sands.

Provincial and territorial regulations

Provincial and territorial regulations also contribute to the regulatory framework for metal and non-metal mining that affects fish.

Source: Based on information from Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada

2.4 Non-metal mines, such as potash, coal, and oil sands mines, are not subject to specific regulations under the Fisheries Act. As in industries like agriculture and construction, non-metal mines other than diamond mines are not permitted to release any effluent containing harmful substances into a body of water where fish are present. The requirements for non-metal mines are therefore more stringent than those for metal mines.

2.5 The federal government has jurisdiction over fisheries. It regulates certain activities to manage the risks of mining effluent on fish and their habitat, primarily through two departments:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada administers and enforces the pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act and its regulations, including the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada has the authority to approve mining activities that may cause serious harm to fish and their habitat. Before undertaking any activities, mining companies must submit plans to compensate for the loss of fish habitat. The Department then monitors whether companies implemented these plans. The Department must also provide this information to Environment and Climate Change Canada.

2.6 Provincial and territorial governments impose other regulations on mining activities, because they are responsible for regulating the extraction of natural resources, such as minerals and coal.

2.7 In the 2009 Spring Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 1—Protecting Fish Habitat, we examined how Environment and Climate Change Canada (then named Environment Canada) and Fisheries and Oceans Canada carried out their responsibilities to protect fish habitat and prevent pollution under the Fisheries Act.

2.8 We reported that the departments could not demonstrate that they adequately protected fish habitat. We recommended that Environment and Climate Change Canada identify, assess, and address significant risks of non-compliance.

2.9 In 2015, Canada committed to achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This audit supports the goal of responsible consumption and production (Goal 12 of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals),Definition i which sets a target to significantly reduce the release of chemicals and waste into air, water, and soil by 2020, to minimize their adverse impact on human health and the environment.

Focus of the audit

2.10 This audit focused on whether Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada protected fish and their habitat from mining effluent at active mine sites, in accordance with the Fisheries Act and the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations. Our audit examined three key aspects of the departments’ mandates:

- oversight by both departments of metal mining companies’ actions to minimize harm to fish and their habitat from storage of mine waste,

- monitoring by Environment and Climate Change Canada of the environmental effects of metal mines on fish and their habitat, and

- enforcement by Environment and Climate Change Canada of metal and non-metal mining companies’ compliance with the Fisheries Act and mining regulations.

2.11 This audit is important because Canadians rely on the federal government to mitigate the effect of mining effluent on fish and their habitat.

2.12 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

2.13 Overall, we found that Environment and Climate Change Canada took steps to protect fish and their habitat from metal mining effluent. These steps included enforcement action to address non-compliance with requirements related to mining effluent.

2.14 However, we found that the frequency of on-site inspections was significantly lower in Ontario than in other regions. In addition, reporting on mine site compliance with requirements was incomplete. Furthermore, the Department had not carried out a comprehensive risk analysis to prioritize inspections of non-metal mines.

2.15 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada met requirements to protect fish and their habitat from mining effluent. Both departments reviewed mining companies’ plans to compensate for loss of fish and their habitat before recommending that mine waste be disposed of. However, we found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada needed to improve monitoring of these plans to ensure that they were actually carried out.

Managing effects of mine waste and effluent on fish and their habitat

Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not always monitor whether companies carried out their plans to offset harm to fish

2.16 We found that both Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada took steps to ensure that metal mining companies minimized or offset the harm to fish and their habitat when using bodies of water as tailings impoundment areas.Definition ii These steps included requiring mining companies to develop plans to compensate for the loss of fish habitat.

2.17 However, Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not always monitor whether mining companies carried out their plans to counteract harm to fish and their habitat when the companies built tailings impoundment areas.

2.18 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Reviewing alternatives for mine waste disposal

- Consulting with the public and Indigenous groups

- Assessing fish habitat compensation plans

- Monitoring implementation of fish habitat compensation plans

2.19 This finding matters because the use of natural bodies of water for mine waste disposal and the construction of mine waste facilities can be harmful to fish and their habitat. It is important to offset this harm, where possible, by creating new fish habitat or improving existing habitat.

2.20 Tailings impoundment areas. Storage of metal mine waste in a tailings impoundment area over a fish-bearing body of water is subject to certain conditions (Exhibit 2.2). A structural breach of a tailings impoundment area could release effluent that is lethal to fish.

Exhibit 2.2—Mining companies use tailings impoundment areas to store harmful mining by-products

Photo: Mathieu Dupuis / Agnico Eagle Mines Limited

2.21 Mining companies. In their proposals to use fish-bearing bodies of water for tailings impoundment areas, companies must demonstrate that depositing mine waste into a body of water is the best option. They must consider this option from an environmental, technical, and socio-economic perspective and compare it with other options, such as depositing mine waste on land.

2.22 Once a proposal is approved, an amendment must be made to the regulations. As of June 2018, mine waste disposal was allowed in 42 bodies of water ranging in size from parts of streams to small lakes. Their total combined surface area was about 39 square kilometres.

2.23 Mining companies must develop and implement fish habitat compensation plans to mitigate the loss of fish when fish habitat is used for mine waste disposal. These compensation plans must do the following:

- outline how mine waste may affect fish habitat,

- determine how to offset the loss of fish and their habitat,

- assess both the time and cost required to implement the plan, and

- include ways to verify the plan’s effectiveness.

2.24 Environment and Climate Change Canada. Environment and Climate Change Canada is required to consult with interested parties and with Indigenous groups. In particular, the Department must present the mining company’s proposal and plans to compensate for the loss of fish, must seek and consider comments, and must publicly report the results of the consultations (Exhibit 2.3).

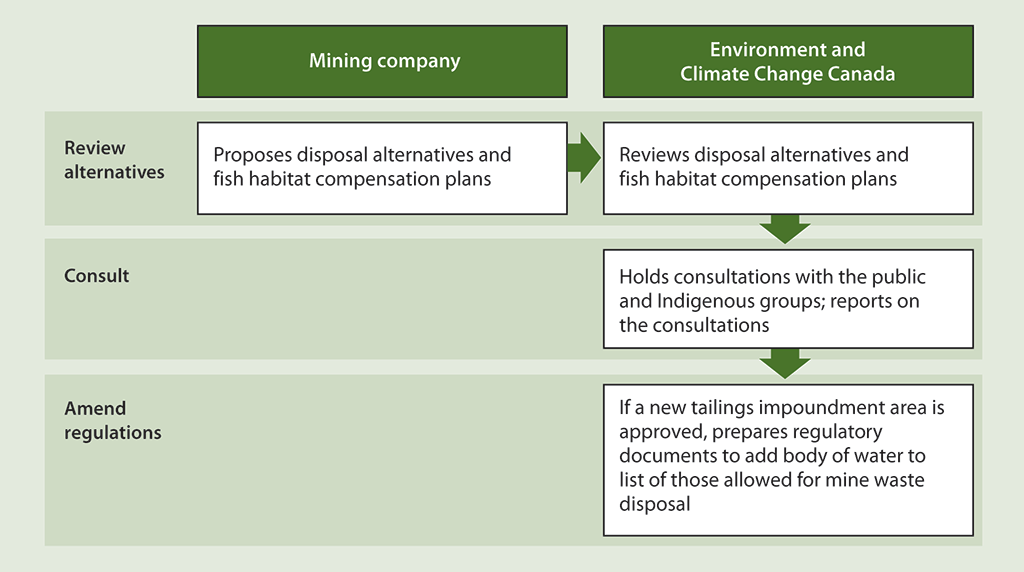

Exhibit 2.3—Environment and Climate Change Canada reviews proposals for mine waste disposal and consults with the public

Source: Based on information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Exhibit 2.3—text version

This diagram illustrates the process that a mining company and Environment and Climate Change Canada follow when a mining company submits a proposal for a new area for mine waste disposal.

- Review alternatives. The mining company proposes disposal alternatives and fish habitat compensation plans. Environment and Climate Change Canada then reviews these proposed alternatives and compensation plans.

- Consult. Environment and Climate Change Canada holds consultations with the public and Indigenous groups and then reports on the consultations.

- Amend regulations. If a new tailings impoundment area is approved, Environment and Climate Change Canada prepares regulatory documents to add the body of water to the list of those allowed for mine waste disposal.

Source: Based on information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

2.25 Both Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada must review fish habitat compensation plans.

2.26 Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Fisheries and Oceans Canada assesses the impact that the tailings impoundment areas and their construction will have on fish and their habitat. In these assessments, the Department reviews information on the fish species and the loss of habitat, mitigation measures to compensate for the loss, and allocation of funds to cover these measures.

2.27 Fisheries and Oceans Canada also approves construction work for new tailings impoundment areas. In addition, the Department monitors whether mining companies have implemented their fish habitat compensation plans. Exhibit 2.4 outlines the required processes and responsibilities.

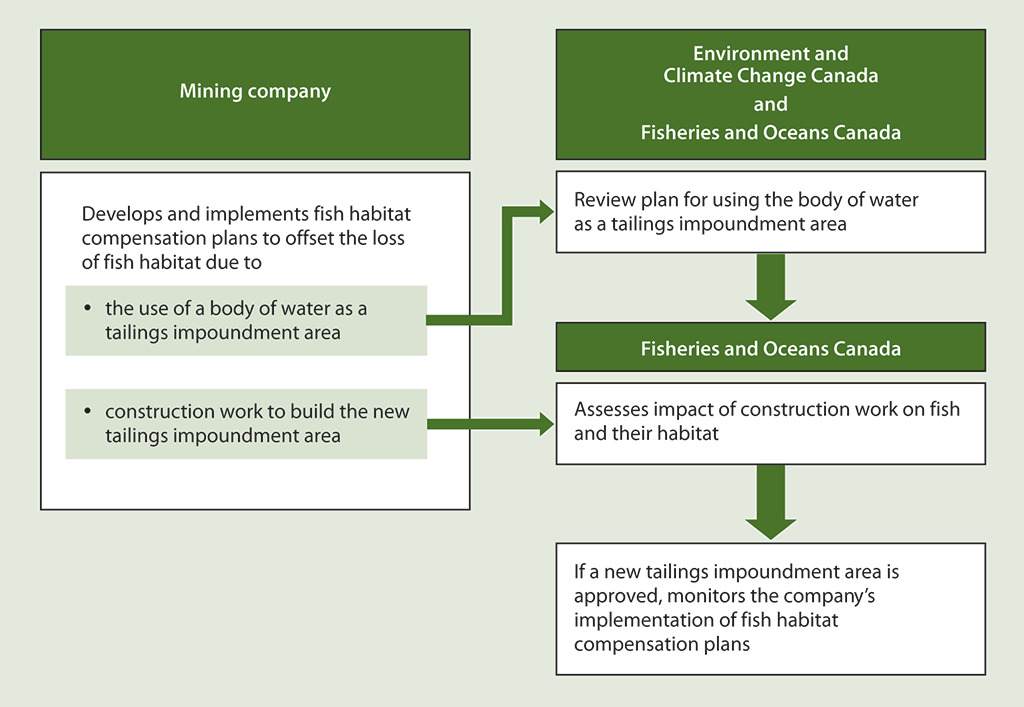

Exhibit 2.4—Plans to offset loss of fish and their habitat must be assessed, authorized, and monitored

Source: Based on information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Exhibit 2.4—text version

This diagram illustrates the process followed by Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada for assessing, authorizing, and monitoring a mining company’s plans for offsetting the loss of fish and their habitat.

- The mining company develops and implements fish habitat compensation plans to offset the loss of fish habitat that would result from using a body of water as a tailings impoundment area, and from the impact of construction work needed to build this new area.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada then review the plan for using the body of water as a tailings impoundment area.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada assesses the impact of construction work on fish and their habitat.

- If a new tailings impoundment area is approved, Fisheries and Oceans Canada monitors the company’s implementation of fish habitat compensation plans.

Source: Based on information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

2.28 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.39.

2.29 What we examined. We examined seven metal mine projects to determine whether Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada conducted the required reviews and consultations before recommending that waters with fish be used as new tailings impoundment areas. We also assessed whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada monitored the mining companies’ implementation of their fish habitat compensation plans.

2.30 Reviewing alternatives for mine waste disposal. We found that in all seven projects, Environment and Climate Change Canada reviewed mining companies’ assessments of alternatives for metal mine waste disposal. Often, the Department asked for additional information when the proposals for alternatives for mine waste disposal did not meet the guidelines. The Department then publicly reported on the mining companies’ proposed alternatives for mine waste disposal and the fish habitat compensation plans.

2.31 Consulting with the public and Indigenous groups. We found that, as required, Environment and Climate Change Canada consulted the public and Indigenous groups before recommending the use of bodies of water for tailings impoundment areas. In most cases, these consultations occurred during, or overlapped with, the environmental assessment. These consultations were an opportunity for the public and Indigenous groups to comment early in the process on the proposed alternatives for mine waste disposal.

2.32 For example, we found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did the following:

- invited Indigenous groups and interested parties to meetings to outline the process and discuss the impact of proposed tailings impoundment areas,

- advertised the meetings in local newspapers and informed the public where to find relevant information,

- provided responses to comments raised by interested parties, and

- publicly reported the results of the consultation.

2.33 Some interested parties continued to oppose the disposal of mine waste in bodies of water. However, we found that the Department was able to provide a rationale for its decisions.

2.34 Assessing fish habitat compensation plans. We found that both Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada reviewed fish habitat compensation plans, as required.

2.35 We also found that Environment and Climate Change Canada intervened when requirements for fish habitat compensation plans were not met. The Department did not authorize the deposit of mine waste into bodies of water when mining companies did not fulfill all conditions.

2.36 We found that in all required cases, Fisheries and Oceans Canada authorized construction of tailings impoundment areas only after the mine sites had submitted fish habitat compensation plans. However, we found that half of the compensation plans that were related to construction work missed some detailed measures to address the loss of fish and their habitat. For example, some plans lacked measures to verify their effectiveness and cost. Others lacked details on contingency actions to take if measures were not successful. These detailed measures are important elements in fish habitat compensation plans.

2.37 Monitoring implementation of fish habitat compensation plans. We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada monitored only 60% of the compensation plans for the tailings impoundment areas that used existing bodies of water. The Department monitored 90% of compensation plans for new construction work.

2.38 For the cases in which Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not conduct monitoring, it also did not review the mining companies’ reports or conduct site visits. As a result, the Department did not always know whether the mining companies performed their planned actions to offset the loss of fish and their habitat.

2.39 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should ensure that all fish habitat compensation plans include detailed measures to address the loss of fish and their habitat, and it should monitor mining companies’ implementation of these plans.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Since 2012, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has had in place the Applications for Authorization under Paragraph 35(2)(b) of the Fisheries Act Regulations which, among other things, set out minimum information requirements to deem an application complete. Since the coming into force of these regulations, proponents seeking a Fisheries Act authorization are legally required to provide the Department with detailed information on their proposed offsetting plan or plans, including contingency measures and an estimate of implementing each element of an offsetting plan.

With regard to monitoring, over the past number of years, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has made efforts to monitor projects near water to ensure compliance with legislation and regulations. Although much progress has been made, the Department recognizes that there is still work to be done with respect to monitoring the adequacy of the offsetting for works, undertakings, or activities that required an authorization under the Fisheries Act or its regulations, such as tailings impoundment areas. As a first step, Fisheries and Oceans Canada is currently revitalizing its monitoring program to ensure the sustainability and ongoing productivity of commercial, recreational, and Indigenous fisheries. Moreover, Fisheries and Oceans Canada also struck in 2017 an agreement with Environment and Climate Change Canada that establishes clear roles and responsibilities and provides operational guidance with regard to the administration and implementation of the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations. The target for implementation of the revitalized monitoring program is April 2020.

Environment and Climate Change Canada monitored the effects of metal mining effluent on fish and their habitat

2.40 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada met its requirements to monitor metal mining effluent. The Department ensured that mining companies submitted data on the environmental effects of metal mining effluent on fish and their habitat, and on the cause of these effects. It also verified that the data was complete and accurate.

2.41 We also found that the Department used this information to help change limits for harmful substances. For example, in response to data showing that certain substances affected the growth and reproduction rates of fish downstream of mines, the Department proposed stricter limits on these substances.

2.42 However, we found that although the Department reported on environmental effects, it did not identify specific mine sites. As a result, Canadians did not know how mining effluent might be affecting their communities.

2.43 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Monitoring environmental effects of metal mines

- Using monitoring information to update regulations

- Reporting environmental effects

- No requirement for companies to fix the problems

2.44 This finding matters because complete and accurate information on the environmental effects of mining effluent is important in assessing how well the regulations protect fish and their habitat. Identifying and reporting on effects by mine site would give Canadians information on potential effects in their communities.

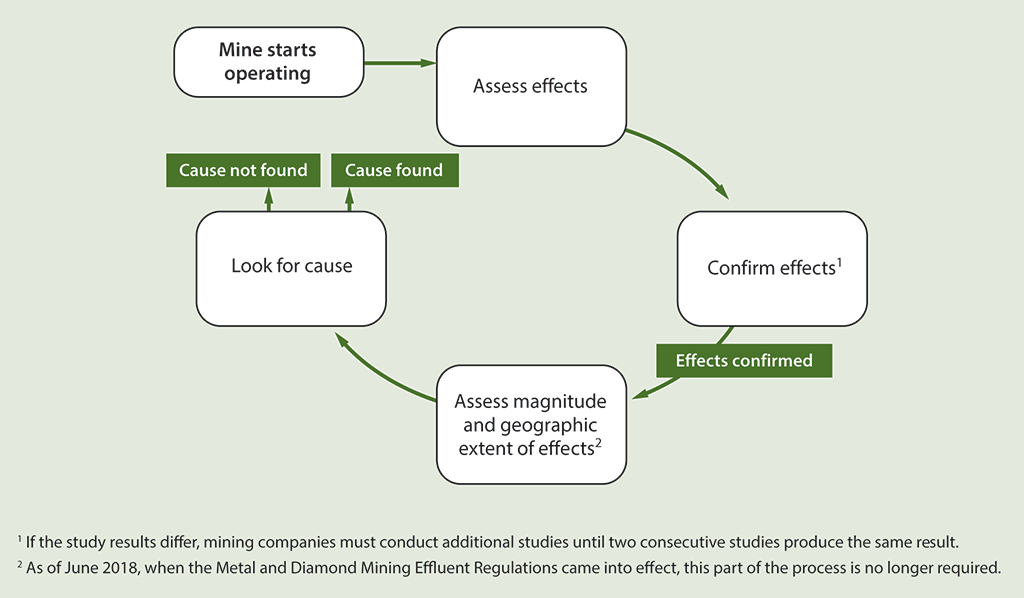

2.45 Regulations require metal mining companies to conduct studies to determine how fish and their habitat are affected by exposure to mining effluent. Environment and Climate Change Canada collects this data and confirms that a minimum of two consecutive studies have the same results. If the results differ, mining companies must conduct additional studies until two consecutive studies produce the same results (Exhibit 2.5).

Exhibit 2.5—Regulations require mining companies to assess the effects of mining effluent on fish and their habitat

Source: Based on information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Exhibit 2.5—text version

This diagram shows the sequence of steps followed by government regulations for assessing the effects of mining effluent on fish and their habitat.

After a mine starts operating, the mining company must conduct a study to assess the effects of mining effluent. The company must then confirm the results of the first assessment. If the study results differ, mining companies must conduct additional studies until two consecutive studies produce the same result.

Once the effects are confirmed, the company can assess the magnitude and geographic extent of the effects and look for their cause. However, as of June 2018, when the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations came into effect, this part of the process is no longer required.

Source: Based on information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

2.46 Monitoring of environmental effects is not required for non-metal mines. An exception exists for diamond mines, which are now included in the amended regulations.

2.47 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 2.56 and 2.58.

2.48 What we examined. We examined whether Environment and Climate Change Canada monitored the environmental effects of metal mining effluent on fish and their habitat, as regulations required, and whether it took action to mitigate the effects.

2.49 Monitoring environmental effects of metal mines. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada developed technical guidelines for companies to study the effects of metal mining effluent on fish. The Department also collected data on environmental effects and verified that it was complete and accurate.

2.50 Using monitoring information to update regulations. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada used the data it collected through its monitoring of environmental effects to propose changes to metal mining regulations.

2.51 For example, the data indicated effects on the growth and reproduction rates of fish downstream of some metal mines. As a result, the Department proposed changes to the allowable limits for several harmful substances in mining effluent. The 2018 Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations introduced stricter limits for some substances that already had limits in place. The regulations also added a substance to the list of substances with authorized limits and imposed even stricter limits for new mines for substances already on the list.

2.52 The amended regulations also introduced additional monitoring requirements for selenium, a by-product of metal and coal mining with probable effects on fish. Department officials told us that they would take into account the information collected from this monitoring when determining whether additional controls were needed for selenium.

2.53 Reporting environmental effects. We found that in 2007, 2012, and 2015, Environment and Climate Change Canada published assessments of the effects of metal mining effluent on the environment. These reports summarized observations at a national level.

2.54 We found, however, that mine sites were not identified by name. As a result, residents of a specific community could not know whether mining effluent affected fish and their habitat in their area.

2.55 In our view, more complete reporting on environmental monitoring of mining effluent would help Canadians understand the effects of mining effluent on fish and their habitat. Increased transparency is also important to support public confidence in government regulation of the mining industry.

2.56 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should publish information on environmental effects with clear identification of mine sites, so that Canadians can know about the effects of mining effluent in specific locations.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is committed to making the data and information it collects, including environmental effects monitoring data, publicly available on the Government of Canada Open Data portal, while meeting its legal obligations related to confidential business information.

2.57 No requirement for companies to fix the problems. We found that the Department did not require mining companies to address the environmental effects identified through monitoring. When companies determined that their effluent affected fish and their habitat, there was no corresponding requirement—including in the amended regulations—to find and implement a solution.

2.58 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should consider measures to address the negative environmental effects of effluent on fish and their habitat when these effects are confirmed through the environmental effects monitoring process.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will develop a paper for consideration by the Minister, by spring 2020, considering options about how to address the residual effects of mining effluent on fish and fish habitat that are identified by the environmental effects monitoring that takes place pursuant to certain Fisheries Act regulations.

Inspecting mine sites and addressing violations

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s frequency of metal mine site inspections was significantly lower in Ontario than in other regions, and its reporting on compliance was incomplete

2.59 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada’s inspections of metal mines were significantly less frequent in Ontario, the region with the highest number of mines in Canada, than in other regions, without any corresponding risk-based rationale. We also discovered that the Department did not usually track its metal mine inspections by mine site. It tracked the inspections by company name—even when a company had several mine sites.

2.60 In addition, we found that the Department did not use complete information when reporting on compliance of metal mines with effluent limits. Reports did not include data on unauthorized effluent discharge from other than the final discharge point, and many mines were excluded because of lack of data.

2.61 Finally, we found that the Department lacked some important controls to ensure the accuracy of companies’ self-reported compliance data.

2.62 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Inspections of metal mines

- Reporting on compliance

- Controls to ensure accuracy of self-reported data

2.63 This finding matters because enforcement activities help to ensure that the metal mining industry complies with requirements designed to protect fish and their habitat. Tracking information by mine site is important because compliance rates can vary by site, even for the same company.

2.64 Environment and Climate Change Canada is responsible for enforcing regulations for metal mining effluent. Enforcement officers review quarterly data submitted by metal mining companies on the concentrations of harmful substances in mining effluent at metal mining sites. They also carry out on-site inspections and conduct their own testing.

2.65 Many mining sites are located in remote locations, and weather conditions limit on-site inspections for much of the year.

2.66 Mining companies submit weekly samples of effluent from mine sites to accredited third-party laboratories for testing. Mining companies are required to immediately notify the Department when monitoring results show that harmful substances exceed the allowed limits, or when a non-authorized release occurs, such as an effluent spill or overflow from containment structures.

2.67 The Department periodically publishes a status report with information on metal mining companies’ compliance with the regulations. It also publishes environmental indicators, such as amount and type of harmful substances in mining effluent.

2.68 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 2.74, 2.78, and 2.81.

2.69 What we examined. We examined whether Environment and Climate Change Canada enforced the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations and reported accurately on whether harmful substances in effluent from metal mines were within the prescribed limits.

2.70 Inspections of metal mines. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not usually track how frequently it carried out on-site inspections of each mine site. It typically tracked this information by company name instead. However, it is important to track the information by site, because one company can have several mining sites with different levels of compliance.

2.71 Using raw data provided by the Department, we calculated that the Department conducted 490 on-site inspections of metal mines between January 2013 and June 2018. On average, this represented one inspection per site every 1.5 years (Exhibit 2.6).

Exhibit 2.6—Between January 2013 and June 2018, Environment and Climate Change Canada inspected metal mines every 1.5 years on average, but less frequently in Ontario

| Region | Number of mine sites | Number of on-site inspections | Average frequency of on-site inspections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario Region | 47 | 71 | Every 3.6 years |

| Quebec Region | 35 | 214 | Every 0.9 years |

| Prairie and Northern Region | 25 | 99 | Every 1.4 years |

| Pacific and Yukon Region | 16 | 59 | Every 1.5 years |

| Atlantic Region | 15 | 47 | Every 1.8 years |

| Total | 138 | 490 | Every 1.5 years |

Source: Based on data from Environment and Climate Change Canada

2.72 We found that the frequency of on-site inspections was significantly lower in Ontario than in other regions. We did not find any risk-based rationale for the lower frequency.

2.73 We also found that during this five-and-a-half-year period, 5 of the 47 Ontario mine sites received no inspections, and an additional 18 mine sites were inspected only once.

2.74 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should review its enforcement plan to ensure that it conducts sufficient on-site inspections of metal mines, and it should track inspections by mine site.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is developing a risk framework that takes into account risks to the environment and human health, including from non-compliance with the Department’s laws and regulations. The risk framework will be completed in 2020 and will be used to inform the Department’s enforcement planning and priorities, including metal and non-metal mines.

The Department can track inspections by mine site, and it is being done when warranted. By 2021, the Department will develop a more effective way to track data on metal and non-metal mines at the site.

2.75 Reporting on compliance. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not have complete and up-to-date information on metal mines’ compliance with effluent limits. Its 2016 status report indicated high compliance (94% to 99%) for mines that provided effluent monitoring data. However, this information does not present an accurate picture of the overall compliance rate, because 35% of mines did not provide complete information, and some mines in this group did not submit any effluent monitoring reports.

2.76 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada reported only on data from effluent samples taken from the final discharge point of each site. The Department provided no information about spills and unauthorized effluent discharge other than from the final discharge point. As a result, the Department’s reports lacked a complete picture of the mining sites’ effects on fish and their habitat.

2.77 We also found that Environment and Climate Change Canada’s reporting was not up to date. For example, the 2016 status report on metal mine compliance was not issued until 2018. At the time of the audit, the Department had its 2017 data but had not yet analyzed it.

2.78 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should use complete and up-to-date information to report on compliance with the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will develop a paper, by spring 2020, on options for collecting and communicating additional information related to compliance from regulated mines (for example, reports of releases of unauthorized effluent).

2.79 Controls to ensure accuracy of self-reported data. We found that mining companies input data on harmful substances into Environment and Climate Change Canada’s system manually, which increased the potential for error. The system flagged figures that exceeded the set limits for these substances, and the Department’s enforcement officers then reviewed these figures. However, the officers did not usually review figures below the set limits.

2.80 We also found that enforcement officers did not systematically review laboratory analysis results. Although some officers checked the data to ensure consistency, others did not. Consequently, the Department’s reporting could have incorporated erroneous information.

2.81 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should improve the method of data entry in its system and implement consistent approaches to validating information provided by metal mines.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is developing a new Mining Effluent Reporting System. As part of that work, the Department is considering options for the electronic uploading of data, with a view to minimizing data entry errors and reducing the administrative burden on regulatees.

The Department will also develop standard operating procedures to accompany the new reporting system.

Environment and Climate Change Canada inspected non-metal mines less often than metal mines

2.82 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada had no comprehensive risk analysis as the basis for inspecting non-metal mines. Therefore, the Department lacked sufficient information to determine the appropriate number and frequency of non-metal mine inspections. Inspections of non-metal mines occurred mostly in response to reports of spills and releases of harmful substances.

2.83 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

2.84 This finding matters because companies are not permitted to release any harmful substances from non-metal mines into any body of water with fish.

2.85 Mining companies do not need to submit any reports that monitor effluent release from non-metal mines into bodies of water with fish, because no such release is permitted. Environment and Climate Change Canada may inspect non-metal mines to ensure that releases of harmful substances do not occur.

2.86 Environment and Climate Change Canada has an annual process to set national priorities for all of its environmental enforcement work. This work includes enforcing the regulations and applicable provisions of both the Fisheries Act and the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. Given that more than 40 regulations have been made under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, this process can be complex.

2.87 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.97.

2.88 What we examined. We examined whether Environment and Climate Change Canada enforced the pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act for non-metal mines.

2.89 Analyzing risk for non-metal mines. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada established national enforcement priorities, but that it did so without a comprehensive risk analysis for non-metal mines. Between 2013 and 2015, the Department identified the need to establish a risk-based strategy for non-metal mines, but it did not develop such a strategy.

2.90 We also found that between 2013 and 2015, the Department launched a project targeting 67 non-metal mines across Canada. However, the Department completed only 44 (66%) of the planned inspections.

2.91 Department officials told us that they had stopped inspections of non-metal mines because they had found a high level of compliance. However, in our view, completing the planned inspections and documenting the results could have been useful to identify risk levels for different non-metal subsectors, such as potash and coal. It also could have been useful in prioritizing future enforcement activities for non-metal mines.

2.92 We also found that the Department had no consolidated information about the overall non-metal mining sector and its subsectors in Canada. This lack of information made it difficult for the Department to understand the overall non-metal sector and to carry out comprehensive risk analyses. This information is critical to identifying priorities to protect fish and their habitat.

2.93 Tracking inspections of non-metal mines. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada’s enforcement database did not track inspections for non-metal mines as a separate group. Data from these inspections was included together with information from inspections of other sectors, such as agriculture and construction.

2.94 According to our analysis, we found that the Department conducted approximately 270 on-site inspections of Canada’s 117 non-metal mines during our audit period. This meant that on average, each mine was inspected only once every 2.4 years. This frequency was lower than the average inspection frequency for metal mines, which was once every 1.5 years.

2.95 Department officials said that their priority was to enforce sectors subject to specific regulations, such as metal mining. Therefore, enforcement expectations were not the same for non-metal mining, even though both sectors were subject to Fisheries Act requirements.

2.96 In our view, inspecting non-metal mines regularly is important because the release of effluent with substances harmful to fish is prohibited for these mines, and the companies are not required to submit any effluent monitoring reports.

2.97 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should undertake the following activities in administering and enforcing the pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act for non-metal mines:

- maintain consolidated information for the non-metal mine sector and its subsectors,

- carry out a full risk-based analysis of non-metal mines to determine how to prioritize this sector’s enforcement,

- conduct inspections based on this analysis, and

- track enforcement activities by type of mine.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is developing a risk framework that takes into account risks to the environment and human health, including from non-compliance with the Department’s laws and regulations. The risk framework will be completed in 2020 and will be used to inform the Department’s enforcement planning and priorities, including metal and non-metal mines.

Modifications as to how the Enforcement Branch tracks activities by type of mine and maintains information will be consistent with the risk framework.

Environment and Climate Change Canada addressed violations of regulations at both metal and non-metal mine sites

2.98 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada addressed violations of regulations at metal and non-metal mine sites. Enforcement actions ranged from written warnings to prosecutions, which in some cases resulted in large penalties.

2.99 We found, however, that the Department usually tracked violations by company rather than by mine site, although tracking by mine site would have yielded more useful data. We also found that before 2017, the Department rarely recorded dates of alleged violations.

2.100 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

2.101 This finding matters because violations of regulations and legislation must be addressed to ensure that mining companies protect fish and their habitat from mining effluent.

2.102 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 2.108 and 2.110.

2.103 What we examined. We examined whether Environment and Climate Change Canada responded to alleged violations of regulations and legislation.

2.104 Enforcement actions. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada had a range of enforcement actions to address non-compliance with mining effluent requirements. For minor violations, enforcement officers could issue written warnings. For severe violations, court action was available (Exhibit 2.7).

Exhibit 2.7—Environment and Climate Change Canada took various types of enforcement actions to address alleged violations of regulations and legislation at mining sites from January 2013 to August 2018

Enforcement measures if a violation is found

| Enforcement action | Description | Number of actionsnote a |

|---|---|---|

|

Written warnings |

Written warnings are formal written notices to inform mining companies of minor violations and to request corrective action. A warning is issued in cases of minimal harm when the alleged violator has made reasonable efforts to fix the negative impact. |

590note b |

|

Written directions |

Written directions are official instructions that oblige mining companies to take all reasonable actions to remedy the negative effects of harmful substances or reduce environmental damages. Written directions are issued when immediate action is necessary to counteract adverse effects of a deposit of a harmful substance, or to prevent a serious and imminent deposit of a harmful substance. |

267 |

Court actions resulting from enforcement activities

| Enforcement action | Description | Number of actionsnote a |

|---|---|---|

|

Prosecutions |

Prosecution is a legal proceeding to determine whether the accused is guilty of committing an offence under the Fisheries Act. |

136note c |

|

Convictions |

Convictions are the number of counts for which a subject has been found guilty or pleaded guilty as a result of prosecutions. |

97 |

Source: Based on information from Environment and Climate Change Canada

2.105 We found that from April 2014 to June 2018, mining companies convicted under the Fisheries Act were required by court orders to pay approximately $16.6 million in penalties to Environment and Climate Change Canada. The penalties ranged from $10,000 to $7.5 million. We noted a recent trend toward larger penalties.

2.106 However, for both metal and non-metal mines, we found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not track data on alleged violations by mine site—it usually tracked this data by company. This meant that the Department could not clearly pinpoint areas for follow-up.

2.107 In addition, before 2017, the Department’s data rarely indicated when the alleged violations occurred. Without this specific information, the Department could not easily determine the frequency of repeated alleged violations by mine site and respond appropriately.

2.108 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should track alleged violations by specific mine site in order to have a comprehensive understanding of compliance by mine site.

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada can track alleged violations by mine site, and it is being done when warranted. By 2021, the Department will develop a more systematic and effective way to track data on compliance by metal and non-metal mines at the site level.

2.109 Additional enforcement measures. We found that further enforcement measures were needed to address administrative violations. For example, under other environmental legislation, some enforcement officers can issue fines, tickets, or administrative monetary penalties when appropriate. The authority to use additional enforcement measures would require legislative amendments to the Fisheries Act.

2.110 Recommendation. Environment and Climate Change Canada should work with Fisheries and Oceans Canada to identify additional types of enforcement measures that could effectively address violations of the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations.

The departments’ response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada will work together to determine whether additional enforcement measures would better address violations of the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations and, more generally, under the pollution prevention regime of the Fisheries Act.

Conclusion

2.111 We concluded that Environment and Climate Change Canada protected fish and their habitat from metal mining effluent, in accordance with the Fisheries Act and Metal Mining Effluent Regulations. This protection included enforcement action to address non-compliance with requirements related to mining effluent. However, the frequency of inspections in Ontario, the region with the highest number of metal mines in Canada, was significantly lower than in other regions. In addition, reporting on mine site compliance with requirements was incomplete. Furthermore, the Department did not carry out a comprehensive risk-based analysis for non-metal mines.

2.112 We also concluded that Fisheries and Oceans Canada met requirements to protect fish and their habitat from mining effluent. Both departments reviewed mining companies’ plans to compensate for loss of fish and their habitat before allowing the companies to dispose of mine waste in tailings impoundment areas. However, Fisheries and Oceans Canada needed to improve its monitoring of these plans to ensure that the plans were actually carried out.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on protecting fish from mining effluent. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the departments’ actions in protecting fish from mining effluent complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada protected fish and their habitat from mining effluent, in accordance with the Fisheries Act and the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations.

Scope and approach

The federal organizations included in this audit were Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

We gathered audit evidence by reviewing documents; interviewing federal officials, industry representatives, and third-party stakeholders; reviewing files; and visiting selected mining facilities. Our analysis focused on data that preceded the amendment of the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations on 1 June 2018.

This audit did not examine inactive and abandoned mines, nor did it assess the impact of mining effluent on groundwater and land, or how mining effluent might directly affect human health. We also did not examine financial guarantees in case of unexpected spills or accidents, including financial assurances to close or remediate mines.

This audit contributed to Canada’s actions in relation to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 16, which is to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.”

Criteria

To determine whether Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada protected fish and their habitat from mining effluent, in accordance with the Fisheries Act and the Metal Mining Effluent Regulations, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada has adequately enforced the pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act for mining effluent. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada has adequately monitored the environmental effects of mining effluent. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada have effectively administered and monitored tailings impoundment areas that include water bodies frequented by fish. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between January 2009 and November 2018. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 14 December 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Sharon Clark

Director: Milan Duvnjak

Arethea Curtis

Kristin Lutes

Kajal Patel

Ludovic Silvestre

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Managing effects of mine waste and effluent on fish and their habitat

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.39 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should ensure that all fish habitat compensation plans include detailed measures to address the loss of fish and their habitat, and it should monitor mining companies’ implementation of these plans. (2.34 to 2.38) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Since 2012, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has had in place the Applications for Authorization under Paragraph 35(2)(b) of the Fisheries Act Regulations which, among other things, set out minimum information requirements to deem an application complete. Since the coming into force of these regulations, proponents seeking a Fisheries Act authorization are legally required to provide the Department with detailed information on their proposed offsetting plan or plans, including contingency measures and an estimate of implementing each element of an offsetting plan. With regard to monitoring, over the past number of years, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has made efforts to monitor projects near water to ensure compliance with legislation and regulations. Although much progress has been made, the Department recognizes that there is still work to be done with respect to monitoring the adequacy of the offsetting for works, undertakings, or activities that required an authorization under the Fisheries Act or its regulations, such as tailings impoundment areas. As a first step, Fisheries and Oceans Canada is currently revitalizing its monitoring program to ensure the sustainability and ongoing productivity of commercial, recreational, and Indigenous fisheries. Moreover, Fisheries and Oceans Canada also struck in 2017 an agreement with Environment and Climate Change Canada that establishes clear roles and responsibilities and provides operational guidance with regard to the administration and implementation of the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations. The target for implementation of the revitalized monitoring program is April 2020. |

|

2.56 Environment and Climate Change Canada should publish information on environmental effects with clear identification of mine sites, so that Canadians can know about the effects of mining effluent in specific locations. (2.53 to 2.55) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is committed to making the data and information it collects, including environmental effects monitoring data, publicly available on the Government of Canada Open Data portal, while meeting its legal obligations related to confidential business information. |

|

2.58 Environment and Climate Change Canada should consider measures to address the negative environmental effects of effluent on fish and their habitat when these effects are confirmed through the environmental effects monitoring process. (2.57) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will develop a paper for consideration by the Minister, by spring 2020, considering options about how to address the residual effects of mining effluent on fish and fish habitat that are identified by the environmental effects monitoring that takes place pursuant to certain Fisheries Act regulations. |

Inspecting mine sites and addressing violations

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.74 Environment and Climate Change Canada should review its enforcement plan to ensure that it conducts sufficient on-site inspections of metal mines, and it should track inspections by mine site. (2.70 to 2.73) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is developing a risk framework that takes into account risks to the environment and human health, including from non-compliance with the Department’s laws and regulations. The risk framework will be completed in 2020 and will be used to inform the Department’s enforcement planning and priorities, including metal and non-metal mines. The Department can track inspections by mine site, and it is being done when warranted. By 2021, the Department will develop a more effective way to track data on metal and non-metal mines at the site. |

|

2.78 Environment and Climate Change Canada should use complete and up-to-date information to report on compliance with the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations. (2.75 to 2.77) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will develop a paper, by spring 2020, on options for collecting and communicating additional information related to compliance from regulated mines (for example, reports of releases of unauthorized effluent). |

|

2.81 Environment and Climate Change Canada should improve the method of data entry in its system and implement consistent approaches to validating information provided by metal mines. (2.79 to 2.80) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is developing a new Mining Effluent Reporting System. As part of that work, the Department is considering options for the electronic uploading of data, with a view to minimizing data entry errors and reducing the administrative burden on regulatees. The Department will also develop standard operating procedures to accompany the new reporting system. |

|

2.97 Environment and Climate Change Canada should undertake the following activities in administering and enforcing the pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act for non-metal mines:

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada is developing a risk framework that takes into account risks to the environment and human health, including from non-compliance with the Department’s laws and regulations. The risk framework will be completed in 2020 and will be used to inform the Department’s enforcement planning and priorities, including metal and non-metal mines. Modifications as to how the Enforcement Branch tracks activities by type of mine and maintains information will be consistent with the risk framework. |

|

2.108 Environment and Climate Change Canada should track alleged violations by specific mine site in order to have a comprehensive understanding of compliance by mine site. (2.104 to 2.107) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada can track alleged violations by mine site, and it is being done when warranted. By 2021, the Department will develop a more systematic and effective way to track data on compliance by metal and non-metal mines at the site level. |

|

2.110 Environment and Climate Change Canada should work with Fisheries and Oceans Canada to identify additional types of enforcement measures that could effectively address violations of the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations. (2.109) |

The departments’ response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada will work together to determine whether additional enforcement measures would better address violations of the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations and, more generally, under the pollution prevention regime of the Fisheries Act. |