2015 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 4—Access to Health Services for Remote First Nations Communities

2015 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 4—Access to Health Services for Remote First Nations Communities

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Nursing stations

- Health Canada did not ensure that nurses had completed mandatory training courses

- Health Canada had not put in place supporting mechanisms for nurses who performed some activities beyond their legislated scope of practice

- Health Canada could not demonstrate whether it had addressed nursing station deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes

- Health Canada had not assessed the capacity of nursing stations to provide essential health services

- Medical transportation benefits

- Support allocation and comparable access

- Coordination of health services among jurisdictions

- Nursing stations

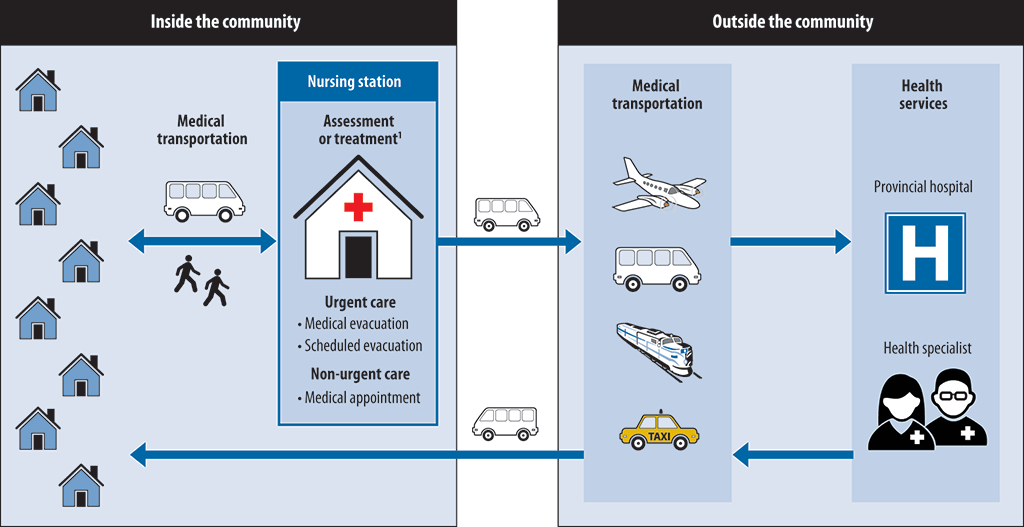

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 4.1—Nursing stations provide the first point of contact for health services in remote First Nations communities

- 4.2—Only 1 of 45 nurses had completed all five of Health Canada’s mandatory training courses selected for examination

- 4.3—Health Canada lacked sufficient documentation to demonstrate that medical transportation benefits were administered in accordance with selected principles of the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework

Performance audit reports

This report presents the results of a performance audit conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada under the authority of the Auditor General Act.

A performance audit is an independent, objective, and systematic assessment of how well government is managing its activities, responsibilities, and resources. Audit topics are selected based on their significance. While the Office may comment on policy implementation in a performance audit, it does not comment on the merits of a policy.

Performance audits are planned, performed, and reported in accordance with professional auditing standards and Office policies. They are conducted by qualified auditors who

- establish audit objectives and criteria for the assessment of performance;

- gather the evidence necessary to assess performance against the criteria;

- report both positive and negative findings;

- conclude against the established audit objectives; and

- make recommendations for improvement when there are significant differences between criteria and assessed performance.

Performance audits contribute to a public service that is ethical and effective and a government that is accountable to Parliament and Canadians.

Introduction

Background

Remote First Nations communities—First Nations communities for which year-round access to provincial health care services is either non-existent or severely limited.

Contribution—A transfer payment subject to performance conditions specified in a funding agreement. A contribution is to be accounted for and is subject to audit.

Source: Policy on Transfer Payments, Treasury Board, 2012

Clinical and client care services—Services provided by Health Canada that consist of urgent and non-urgent care.

- Urgent care involves immediately assessing a patient to determine the severity of a serious illness or injury and the type of care needed. The patient may be given stabilizing treatment and be immediately transported outside the community to a provincial hospital or other facility, or may be kept under observation at the nursing station.

- Non-urgent care involves assessing, identifying problems, and generating a case management plan for a patient seeking treatment for a specific, non-life-threatening health concern. This type of care may involve transportation to a facility outside the community.

4.1 Health Canada (the Department) supports First Nations through various health programs based on the 1979 Indian Health Policy. Under these programs, the Department provides funding for the delivery of health services in remote First Nations communities, where individuals face significant health challenges and have limited access to provincial health services. According to the Department, support to these communities extends to 85 health facilities, where health services are delivered through collaborative health care teams, led by approximately 400 nurses. These health facilities serve approximately 95,000 First Nations individuals.

4.2 Health Canada also supports First Nations individuals by providing medical transportation benefits when health services are not available within the community. The benefits may be administered through the Department’s regional offices, by First Nations health authorities, or by organizations that have assumed this responsibility under a contribution agreement with the Department.

4.3 According to Department records, Health Canada provided $103 million in the 2013–14 fiscal year for clinical and client care services in Manitoba and Ontario to support nursing stations in which Health Canada nurses are employed. It also provided about $175 million for medical transportation benefits in the two provinces during the same period.

4.4 According to Health Canada, the life expectancy of the First Nations population increased between 1980 and 2010; however, it was about eight years shorter than the life expectancy of other Canadians in 2010. Furthermore, the health status of the First Nations population remained considerably poorer than that of the rest of the Canadian population. For example, First Nations communities face higher rates of chronic and infectious disease, and mental health and substance abuse issues. Poor social determinants in these communities—such as overcrowded housing, high unemployment, and unsafe drinking water—contribute to poorer health outcomes.

Focus of the audit

4.5 This audit focused on whether Health Canada had reasonable assurance that eligible First Nations individuals living in remote communities in Manitoba and Ontario had access to clinical and client care services, and medical transportation benefits.

4.6 This audit is important because First Nations individuals living in remote communities face unique challenges in obtaining essential health services. They rely on the federal government’s support to access health services within their communities, and on federally supported transportation benefits to access health services outside their communities.

4.7 We did not examine the quality of health services and benefits provided, or the adequacy of federal resources spent on supporting First Nations individuals’ access to health services and benefits. Although we spoke to non-federal stakeholders during the audit, we do not comment on their performance.

4.8 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Nursing stations

4.9 Overall, we found that Health Canada nurses working in nursing stations were properly registered with their provincial regulatory bodies, but only 1 of the 45 nurses in our sample had completed all five of Health Canada’s mandatory training courses that we selected for examination.

4.10 Health Canada (the Department) acknowledges that its nurses sometimes work outside their legislated scope of practice in order to provide essential health services in remote First Nations communities. However, we found that Health Canada had not put in place supporting mechanisms that would authorize the nurses to perform activities outside their legislated scope of practice, such as medical directives to allow nurses to perform specific tasks under particular circumstances.

4.11 We also found that Health Canada had identified numerous deficiencies in nursing stations related to health and safety requirements or building codes. For a sample of 30 deficiencies, the Department could not provide evidence that the deficiencies had been addressed. Furthermore, one of the residences at a nursing station that we visited had been unusable for more than two years because the septic system had not been repaired. Consequently, health specialists cancelled their visits to the community.

4.12 Lastly, we found that Health Canada had recently defined essential health services that should be provided in nursing stations. However, the Department had not assessed whether each nursing station had the capacity to provide these services, nor had it informed First Nations individuals what essential services were provided at the station.

4.13 These findings are important because First Nations individuals in remote communities should have access to essential health services from qualified nurses who have the authority to provide these services. Nursing stations that are non-compliant with health and safety requirements or building codes can put patients and staff at risk and may limit access to health services.

4.14 For individuals living in remote First Nations communities, the nursing stations supported by Health Canada are typically the first point of contact for accessing clinical and client care services both inside and outside these communities (Exhibit 4.1). These services are usually provided by nurses working in a challenging environment (that is, remote and isolated communities with significant health needs) and involve

- assessing the patient’s health condition,

- determining whether the need for care is urgent or non-urgent, and

- identifying and taking necessary actions.

Exhibit 4.1—Nursing stations provide the first point of contact for health services in remote First Nations communities

1 To help them with assessment or treatment, nurses may be required to consult a physician directly, either by telephone or by video conference.

Source: Based on Health Canada information

4.15 Clinical and client care services are complemented by a wide range of services funded by Health Canada such as home care, diabetes management, and other public health services such as immunization and maternal-child health.

4.16 According to Health Canada, in Manitoba, there are 22 federally funded nursing stations: 21 operated with Health Canada nurses and 1 operated by the First Nations community. In Ontario, there are 29 federally funded nursing stations: 25 operated with Health Canada nurses and 4 operated by the First Nations communities.

4.17 In the 2013–14 fiscal year, Health Canada’s support for clinical and client care services at nursing stations in Manitoba and Ontario totalled about $55 million and $48 million, respectively.

Health Canada did not ensure that nurses had completed mandatory training courses

4.18 We found that all of the 45 nurses in our sample were registered with their provincial regulatory bodies. We also found that Health Canada had specified mandatory training courses for its nurses to complete; however, only 1 nurse in our sample of 45 had completed all five of the mandatory training courses we selected for examination.

4.19 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.20 This finding matters because the registration of nurses with their provincial regulatory bodies and the completion of mandatory training by nurses provide assurance that First Nations individuals living in remote communities receive care from competent, qualified nurses.

4.21 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.27.

4.22 What we examined. We selected a sample of 45 Health Canada nurses (24 in Manitoba and 21 in Ontario) and reviewed documentation to determine whether these nurses

- were registered with the College of Nurses of Ontario or the College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba (the provincial regulatory bodies), and

- had completed all five of the mandatory training courses specified by Health Canada that we selected for examination.

4.23 Provincial registration of nurses. The College of Nurses of Ontario and the College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba are responsible for establishing standards of practice and the registration of nurses. Standards are aimed at protecting public safety by assuring that nurses are qualified to provide quality and safe care. Health Canada requires nurses who work in remote First Nations communities to be registered in the province in which they work. We found that all 45 nurses in our sample met this requirement.

4.24 Mandatory training courses specified by Health Canada. Health Canada recognizes that, in remote First Nations communities, nurses may face emergency situations that require training beyond what basic nursing education programs provide. The Department specifies mandatory training for these nurses to complete, including courses in areas such as immunization, cardiac life support, and the handling of controlled substances in First Nations health facilities. These courses are provided by external organizations, such as the University of Ottawa’s School of Nursing or the Heart and Stroke Foundation.

4.25 We found that only 1 nurse in our sample of 45 nurses had completed all five of the mandatory training courses we selected for examination (Exhibit 4.2).

Exhibit 4.2—Only 1 of 45 nurses had completed all five of Health Canada’s mandatory training courses selected for examination

| Mandatory training courses specified by Health Canada | Number and percentage of nurses who completed mandatory training courses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manitoba (24 nurses) |

Ontario (21 nurses) |

Total (45 nurses) |

|

| Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) | 8 (33%) | 9 (43%) | 17 (38%) |

| International Trauma Life Support (ITLS) | 10 (42%) | 2 (10%) | 12 (27%) |

| Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) | 10 (42%) | 6 (29%) | 16 (36%) |

| Health Canada’s Nursing Education Module on Controlled Substances in First Nations Health Facilities | 19 (79%) | 12 (57%) | 31 (69%) |

| Immunization Competencies Education Modules | 19 (79%) | 18 (86%) | 37 (82%) |

| Total Health Canada nurses who completed all five courses | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

4.26 The issue of nurses not having completed mandatory training specified by Health Canada was previously raised in a 2010 Health Canada internal audit report. We are concerned that this issue persists and that it could negatively affect the health services provided to First Nations individuals.

4.27 Recommendation. Health Canada should ensure that its nurses working in remote First Nations communities successfully complete the mandatory training courses specified by the Department.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada recognizes that training is very important. Going forward, the Department will strengthen its efforts to meet mandatory training for its nurses and establish processes to monitor compliance and completion rates.

One of the challenges in meeting these requirements has been the significant vacancy and turnover rates in nursing. The first order of priority has been to assign adequate levels of nurses in all nursing stations. Health Canada’s Nurse Recruitment and Retention Strategy (October 2013) is striving to augment and stabilize its nursing workforce in efforts to address these shortages.

Health Canada will work to balance training needs and service to communities, ensuring that training does not result in a loss of services in a community.

Health Canada had not put in place supporting mechanisms for nurses who performed some activities beyond their legislated scope of practice

4.28 According to Health Canada, nurses sometimes work outside their legislated scope of practice in order to provide essential health services in remote First Nations communities. However, we found that the Department had not put in place supporting mechanisms that allowed the nurses to perform these activities.

4.29 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.30 This finding matters because the provincial regulatory framework for nurses defines the activities that they are allowed to perform when providing health services. The purpose of the framework is to protect the public interest by ensuring that nurses provide care within a defined scope of practice.

4.31 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.37.

4.32 What we examined. We reviewed documentation and conducted interviews to determine whether Health Canada nurses working in remote First Nations communities performed activities that were beyond their scope of practice as defined by provincial legislation.

4.33 Nurses’ scope of practice. A nurse’s scope of practice encompasses the activities that a nurse is authorized to perform, which are defined by provincial legislation. The College of Nurses of Ontario and the College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba (the provincial regulatory bodies) govern their nursing practices within the parameters set by provincial laws. According to these bodies, nurses are accountable for practising in compliance with current College standards, and the employer’s role is to establish policies that allow nurses to do so.

4.34 According to Health Canada, while most activities carried out by nurses in their day-to-day work were within their scope of practice, sometimes they worked outside of their scope of practice in order to provide essential health services. Examples of activities that were outside the nurses’ legislated scope of practice included

- prescribing and dispensing certain drugs, such as broad spectrum antibiotics, intravenous medications for cardiac arrest or seizures, and intramuscular injection medications for nausea and vomiting; and

- performing X-ray imaging of the chest and limbs of patients over two years of age.

Nurse practitioners—Registered nurses who have additional education and experience, and are authorized to order and interpret diagnostic tests, communicate diagnoses, prescribe medications, and perform specific medical procedures.

4.35 In 2014, Health Canada had contacted both the College of Nurses of Ontario and the College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba to explore options. According to the Department, the following options were discussed:

- Ensure medical directives are in place so that nurses’ activities beyond the scope of practice are delegated by an appropriate medical professional.

- Work with the provinces to amend the relevant provincial nursing acts and regulations.

- Hire more nurse practitioners.

4.36 We found that, for Health Canada’s nurses, working outside their legislated scope of practice in remote First Nations communities has been a long-standing issue. We also found that the Department had not put in place supporting mechanisms (for example, medical directives) that would allow nurses to provide essential health services that are outside their legislated scope of practice.

4.37 Recommendation. Health Canada should ensure that its nurses are provided with appropriate supporting mechanisms that allow them to provide essential health services that are outside their legislated scope of practice.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada agrees that nurses need appropriate supporting mechanisms to perform their important duties, and a number of mechanisms are already in place.

Health Canada will continue to strengthen and formalize its management and risk control framework for clinical care. Elements of this framework include

- clinical guidelines, standards, and accreditation;

- the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch Nursing Station Formulary and Drug Classification System;

- mandatory nursing training courses;

- formalized access to physicians and nurse practitioners when the situation requires interventions outside the nurses’ legislated scope of practice;

- appropriate medical delegation mechanisms;

- nurse registration; and

- working with the provinces and the nurse regulatory bodies to explore potential strategies to support nurses in remote and isolated First Nations communities.

Health Canada could not demonstrate whether it had addressed nursing station deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes

4.38 Health Canada’s 2005 Framework for Capital Planning and Management requires each nursing station facility to undergo an inspection at least once every five years. Of the eight nursing stations built before 2009 that we reviewed, we found that five had been inspected within the required time period, two had been inspected outside the required time period, and one had not been inspected.

4.39 For the seven inspected facilities, the facility condition reports identified deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes. Of the 30 deficiencies that we reviewed, we found that 26 had not been addressed. According to Health Canada, the remaining 4 had been addressed, but the Department did not provide supporting documentation.

4.40 We also found that Health Canada could not demonstrate whether nursing stations built since 2009 had been constructed according to applicable building codes.

4.41 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.42 This finding matters because compliance with building codes during construction helps avoid errors or omissions that may not be detectable during subsequent inspections. Nursing stations that are non-compliant with health and safety requirements or building codes can put patients and nursing station staff at risk, and may ultimately limit access to health services in remote First Nations communities.

4.43 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 4.53 and 4.56.

4.44 What we examined. We examined a sample of eight nursing stations built before 2009 in remote First Nations communities to determine whether these nursing nations had been inspected within Health Canada’s five-year cycle. Three were in Manitoba, and five were in Ontario. For the inspected nursing stations, we reviewed the most recent facility condition report, from which we selected a sample of 30 identified deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes. We examined these deficiencies (7 in Manitoba and 23 in Ontario) to determine whether Health Canada could demonstrate that actions had been taken to address them.

4.45 We also reviewed documentation for nine nursing stations built or significantly renovated since 2009 in remote First Nations communities to determine whether Health Canada could demonstrate that these facilities had been constructed according to applicable building codes. Seven were in Manitoba, and two were in Ontario.

4.46 Nursing stations built before 2009. Health Canada requires each nursing station facility to undergo an inspection at least once every five years. Health Canada engaged Public Works and Government Services Canada to inspect these facilities and provide a facility condition report. The aim of these reports is to

- identify and describe existing building systems;

- assess the current condition of the systems;

- identify deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes;

- provide recommendations on the need for maintenance and repairs, or for work required to address these deficiencies; and

- provide an estimated cost of the recommended work.

4.47 According to Health Canada, the Department provided about $14 million for minor capital projects and approximately $16 million for operations and maintenance to all First Nations communities in Manitoba and Ontario for the 2013–14 fiscal year.

4.48 Of the eight nursing stations built before 2009, we found that all five nursing stations in Ontario had been inspected within the required time frame. In Manitoba, none of the three nursing stations had been inspected within the last five years: two were last inspected in 2004 and one had never been inspected.

4.49 We found that a facility condition report had been prepared for each of the seven facilities that had been inspected. All seven facility condition reports identified deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes. Our sample of 30 deficiencies included the following:

- elements of the fire alarm or emergency power systems that did not meet the applicable codes;

- cooling and ventilation systems that did not manage temperature and moisture levels to support a safe environment for staff and patients;

- stairs, ramps, and doors that were unsafe or did not meet required codes; and

- accessibility that was inadequate for mobility-impaired individuals.

4.50 According to Health Canada, 26 of the 30 deficiencies that we reviewed had not been addressed. In Ontario, 23 deficiencies related to five nursing stations—and in Manitoba, 3 deficiencies related to two nursing stations—had not been addressed. Health Canada told us that 4 of the 30 deficiencies had been addressed, but the Department did not provide supporting documentation.

4.51 During our community visits, nursing staff informed us of health and safety issues at their facilities, including

- the lack of an emergency back-up generator,

- improper door seals for the X-ray room, and

- defective locks controlling access to the nursing station.

4.52 In one community we visited, we found unaddressed health and safety issues in the nursing station and in the residences used to accommodate visiting health care providers. The ventilation and air conditioning in both the nursing station and residences needed to be repaired. According to Health Canada officials, these deficiencies were causing heat-related symptoms for staff and patients. Furthermore, one of the residences had been unusable for more than two years because the septic system had not been repaired. Consequently, health specialists cancelled their visits to the community.

4.53 Recommendation. Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to ensure that nursing stations are inspected on a regular basis and that deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes are addressed in a timely manner.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada will continue to work with First Nations to ensure that buildings are inspected on a regular basis and that deficiencies are addressed in a timely manner. In particular, Health Canada will standardize procedures to ensure facility condition reports are systematically shared with building owners. Health Canada will also make more explicit the requirements and timelines for routine inspections and corresponding repairs, by including relevant requirements in the Health Infrastructure and Capital Protocol.

4.54 Nursing stations built since 2009. Health Canada’s contribution agreements with First Nations communities require that nursing stations be constructed according to applicable building codes. Compliance with building codes during construction is important because errors or omissions may not be detectable during subsequent inspections. According to Health Canada, the Department relies on certificates of substantial completion from an architect or engineer to satisfy itself that the constructed facilities meet applicable code requirements.

4.55 Department records showed that since 2009, Health Canada provided about $55 million to nine First Nations communities (seven in Manitoba and two in Ontario) for the new construction or significant renovation of nine nursing stations. We asked Health Canada officials to provide us with documentation showing that these facilities met the applicable building code requirements. The Department provided certificates of substantial completion for five of the nine facilities. However, we found that these documents

- mainly pertained to the readiness of the facilities for use and to payments under the contracts, and

- did not specify whether the facility had been constructed according to applicable building codes.

4.56 Recommendation. Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to ensure that new nursing stations are built according to applicable building codes.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Ensuring buildings are to code is a priority for Health Canada. The Department has a long-standing process that requires an attestation by an architect or engineer to provide assurance that the construction is completed and is compliant with the applicable building codes. To increase clarity going forward, Health Canada will make adjustments to the process to ensure that the scope of this attestation is clear for all parties involved in a construction project.

Health Canada had not assessed the capacity of nursing stations to provide essential health services

4.57 We found that Health Canada had not assessed whether each nursing station was capable of providing all the health services that the Department had defined as essential in 2013. We also found that Health Canada had not communicated to First Nations individuals what essential services each nursing station provides.

4.58 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.59 This finding matters because Health Canada needs to know whether nursing stations in remote First Nations communities can provide the services it has defined as essential. In addition, First Nations individuals need to know what services nursing stations in their communities provide.

4.60 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 4.64 and 4.65.

4.61 What we examined. We examined whether Health Canada had defined the essential services provided at nursing stations. We also examined whether Health Canada had communicated to First Nations individuals what essential services each nursing station provided.

4.62 Definition and communication of essential health services. In 2013, Health Canada defined the essential health services that each of its nursing stations should provide. According to the Department, the essential services required in each community vary according to the community’s size, geographic location, and health needs. These essential services comprised triage, emergency services, and outpatient non-urgent services.

4.63 We found that the Department had not assessed whether each nursing station was capable of providing all of these essential services. We also found that Health Canada had not communicated to First Nations individuals what essential services the community’s nursing station provided.

4.64 Recommendation. Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to ensure that nursing stations are capable of providing Health Canada’s essential health services.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Allocating nursing resources to support the safe, supportive, and culturally appropriate delivery of health services is a priority for Health Canada. In collaboration with First Nations, Health Canada will review the clinical care complement in an effort to progressively move toward the creation of interprofessional teams where possible to support the culturally appropriate, safe, and effective delivery of essential services.

4.65 Recommendation. Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to communicate what services each nursing station provides.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada, in collaboration with First Nations, will provide a list of all clinical care services offered at each nursing station for communication to community members.

Medical transportation benefits

4.66 Overall, we found that medical transportation benefits were available to First Nations individuals registered in the Indian Registration System, but that those who had not registered may be denied access to these benefits. This is important because First Nations individuals who are denied access to medical transportation benefits may not be able to receive health services that are only available outside their community.

4.67 We also found that Health Canada’s documentation concerning the administration of medical transportation benefits was insufficient. For example, there was lack of documentation to demonstrate that the requested transportation was medically necessary and to confirm that individuals attended the appointments for which they had requested transportation. Sufficient documentation is needed to document decision making and facilitate consistent delivery of benefits.

4.68 Health Canada provides medical transportation benefits so that eligible First Nations individuals can access medically required health services. In 2005, Health Canada released its Medical Transportation Policy Framework, which set out the available benefits and the funding criteria. Under the framework, Health Canada covers the cost of transporting First Nations individuals to the nearest appropriate health professional or health facility to meet their medical needs. Transportation benefits consist of

- ground, air, and water travel;

- living expenses (meals and accommodations);

- transportation costs for health professionals;

- emergency transportation;

- transportation and living expenses for an escort; and

- transportation to addictions treatment and traditional healers.

4.69 Medical transportation benefits are administered either by Health Canada’s regional offices or by First Nations communities under contribution agreements. Health Canada’s expenditures for medical transportation benefits in the 2013–14 fiscal year were $112 million in Manitoba and $63 million in Ontario.

Some First Nations individuals had not registered and were therefore ineligible for Health Canada’s medical transportation benefits

4.70 We found that Health Canada’s medical transportation benefits were available to registered First Nations individuals but that individuals over one year old and not registered in the Indian Registration System may be denied access to these benefits.

4.71 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.72 This finding matters because First Nations individuals who are denied access to medical transportation benefits may not be able to receive health services that are only available outside their community.

4.73 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.81.

4.74 What we examined. We examined a sample of 50 requests to access Health Canada’s medical transportation benefits (25 in Manitoba and 25 in Ontario) during the 2013–14 fiscal year to determine whether First Nations individuals were registered in Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s Indian Registration System and in Health Canada’s Status Verification System. We also examined a sample of 21 births reported in Manitoba during the 2013 calendar year to determine whether these children had been registered in the Indian Registration System.

4.75 Registration of First Nations individuals. The 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework states that to be eligible for medical transportation benefits, an individual must be

- a registered Indian according to the Indian Act, or a child up to one year of age who has an eligible parent; and

- currently registered, or eligible for registration, under a provincial health insurance plan.

4.76 Under the Indian Act, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada is responsible for maintaining the Indian Register, which is the official record identifying all Registered Indians in Canada. First Nations individuals can register as Registered Indians, and record “life events” such as births and deaths, through the Indian Registration System. Registration is voluntary, and First Nations individuals are responsible for providing this information to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

4.77 Health Canada uses information from the Indian Registration System to update the information in its Status Verification System. Health Canada uses its system to determine whether First Nations individuals are eligible for medical transportation benefits.

4.78 We found that all 50 requests for medical transportation benefits were made for First Nations individuals who were registered in Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s Indian Registration System and in Health Canada’s Status Verification System.

4.79 Of the 21 births in Manitoba during 2013 that we sampled, we found that 10 children were registered by their parent(s) and 11 were not. In Ontario, we were not able to determine whether children were registered because Health Canada did not have equivalent detailed birth information. However, in one First Nations community that we visited in Northern Ontario, we were informed that about 50 First Nations individuals had not been registered.

4.80 According to the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework, First Nations individuals over one year old and not registered in the Indian Registration System may be denied access to medical transportation benefits. For example, in emergency situations, a non-registered First Nations individual transported outside the community may be denied transportation benefits to return home.

4.81 Recommendation. Health Canada should work with First Nations communities, and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, to facilitate the registration of First Nations individuals.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada will ensure that information materials about the Indian registration process are available in all nursing stations and will continue to work with partners to improve the availability of information in health facilities.

Health Canada did not sufficiently document the administration of medical transportation benefits

4.82 We found that Health Canada maintained insufficient documentation to demonstrate that medical transportation benefits were administered according to selected principles of the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework. We also found that Health Canada did not analyze denied requests for medical transportation benefits.

4.83 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.84 This finding matters because proper records support effective decision making and facilitate the delivery of benefits. Documented decisions and analysis regarding approved and denied medical transportation benefits also demonstrate that these benefits are administered according to the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework and in compliance with the Treasury Board’s 2009 Directive on Recordkeeping.

4.85 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.91.

4.86 What we examined. We examined the same sample of 50 requests described in paragraph 4.74 to determine whether Health Canada’s regional offices maintained sufficient documentation to demonstrate that medical transportation benefits were administered

- in accordance with selected principles of the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework, and

- in compliance with the Treasury Board’s 2009 Directive on Recordkeeping.

4.87 Documentation and analysis of medical transportation benefits. According to the directive, departments are required to identify and maintain records that support the decision making and delivery of the department’s programs, services, or benefits. Departments are also responsible for establishing and carrying out retention periods for their records. If the department does not have internal guidance on records retention, then Library and Archives Canada’s 2011 Retention Guidelines for Common Administrative Records for the Government of Canada apply. These guidelines state that departments should retain administrative documents, such as those used to administer medical transportation benefits, for at least two years.

4.88 We found that neither Health Canada’s 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework nor its 2008 Medical Transportation Operations Manual specified which documents needed to be retained or for how long.

4.89 We also found that Health Canada’s Manitoba and Ontario regional offices had insufficient documentation to demonstrate that these benefits were administered according to selected principles of the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework. Exhibit 4.3 provides the results of our testing in Manitoba and Ontario. In particular, we found that the regional offices did not have sufficient documentation to confirm the following:

- The medical referral showed the medical necessity of the appointment.

- The required health services were not available in the community.

- The request for a non-medical escort was signed by a medical professional.

- The individual attended the medical appointment.

Exhibit 4.3—Health Canada lacked sufficient documentation to demonstrate that medical transportation benefits were administered in accordance with selected principles of the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework

| Documentation required to support selected principles of 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework | Number and percentage of medical transportation requests that had supporting documentation (2013–14 fiscal year) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Manitoba (25 requests) |

Ontario (25 requests) |

||

| Medically necessary transportation | Medical referral to show that requested medical transportation was required for medical reasons | 0 of 21 a (0%) | 4 of 22 a (18%) |

| Evidence that services obtained outside First Nations communities were not available in community of residence | 0 of 21 a (0%) | 0 of 22 a (0%) | |

| Non-medical escort | Preauthorization of non-medical escort | 18 of 18 b (100%) | 14 of 14 b (100%) |

| Request for non-medical escort, signed by doctor or community health professional | 0 of 13 c (0%) | 5 of 12 c (42%) | |

| Attendance confirmation | Written confirmation from health care professional on whether First Nations individual attended medical appointment | 0 of 24 d (0%) | 9 of 25 (36%) |

a Medical referrals and evidence that services are not available in the community are not required during emergency situations. These requests were not required in 4 cases in Manitoba and in 3 cases in Ontario.

b Among the 50 requests, 18 cases in Manitoba and 14 cases in Ontario requested non-medical escorts. All 32 cases were approved.

c Medical requests for non-medical escorts are not required for minors. These requests were not required in 5 cases in Manitoba and 2 cases in Ontario.

d Because 1 of the 25 requests in Manitoba was denied, an attendance confirmation was required for 24 of them.

4.90 We also found that in Manitoba, approximately 4,700 of 109,000 medical transportation benefit requests (4 percent) were denied by Health Canada’s administrative staff during the 2013–14 fiscal year. In Ontario, we found that about 300 of 61,000 requests (0.5 percent) were denied during the same period. Neither regional office analyzed the overall number of denied requests or the reasons for denial to ensure that these denials were justified according to Health Canada’s 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework.

4.91 Recommendation. Health Canada should maintain sufficient documentation to comply with the Treasury Board’s 2009 Directive on Recordkeeping and to demonstrate that medical transportation benefits are administered according to Health Canada’s 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada’s goal is to ensure that eligible clients receive timely coverage for medical transportation benefits in accordance with the provision of the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework. At the same time, the Department is making efforts to adapt its processes to avoid undue burden on clients and health care professionals. As part of this effort, Health Canada will modify its current guidelines to better align with current operating practices related to the assertion of medical needs and confirmation of attendance.

As recommended, Health Canada will disseminate to its staff clear instructions on the processing and retaining of transitional records necessary for the adjudications of benefits.

Support allocation and comparable access

4.92 Overall, we found that Health Canada (the Department) did not take into account the health needs of remote First Nations communities when allocating its support. Taking into account communities’ health needs is important because it would help to ensure that available departmental support is allocated to areas with the greatest needs and that it contributes to improving the health status of First Nations.

4.93 We also found that Health Canada had not implemented its objective of ensuring that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations. Health Canada needs to know whether its support is providing comparable access so it can make adjustments that may be necessary to ensure its support provides access to an appropriate level of service.

4.94 According to Health Canada’s 2012 First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan, First Nations communities should receive health services and benefits that are responsive to their needs and improve their health status. In our view, to be consistent with this strategic outcome, Health Canada should take into account the needs of remote First Nations communities when allocating its support.

4.95 Health Canada’s stated objective is to ensure that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to the clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations.

Health Canada did not take into account community health needs when allocating its support

4.96 We found that Health Canada did not take into account the health needs of remote First Nations communities when allocating its support for clinical and client care services.

4.97 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.98 This finding matters because taking into account the health needs of communities helps to ensure that available departmental support is allocated to the areas of highest need and contributes to improving the health status of First Nations.

4.99 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.107.

4.100 What we examined. We reviewed Health Canada documentation and a sample of First Nations community health plans. We also interviewed Department officials to determine whether Health Canada had taken into account the health needs of remote First Nations communities when allocating support for clinical and client care services, and medical transportation benefits.

4.101 Community health plans. According to Health Canada, a key objective of a First Nations community health plan is to provide an assessment of the community’s current and future health needs. We selected a sample of 12 remote communities (7 in Ontario and 5 in Manitoba) that received Health Canada support to see whether the Department had used the community health plans when allocating its support.

Block funding—A type of contribution agreement under which recipients determine their health priorities, prepare a health plan, and establish their health management structure. Recipients are allowed to reallocate funds and retain surpluses to reinvest in their health priorities. Annual reports and year-end audit reports are required.

4.102 According to Health Canada, community health plans are required only from communities that receive multi-year block funding for health services. Out of the 12 communities that we reviewed, 3 received block funding (2 in Manitoba and 1 in Ontario) and had provided a copy of their community health plans to Health Canada. In our view, Health Canada could use community health plans to take into account the health needs of the community when allocating funds.

4.103 Levels of nursing staff. Nurses working in nursing stations are employees of Health Canada, providers of services under contract with the Department, or employed by First Nations. We found that the existing complement of nurses in both Manitoba and Ontario was not allocated to First Nations communities on the basis of established community needs.

4.104 According to a 2007 draft report commissioned by Health Canada and the Assembly of First Nations, Health Canada used the Community Workload Increase System as a workload analysis and resource allocation tool from 1991 to 1996. It served as a mechanism to transfer more resources to communities that had demonstrated a high level of need for health providers. The report recommended that Health Canada carry out a similar needs-based approach and that funding be allocated accordingly.

4.105 Health Canada’s regional officials in both Manitoba and Ontario told us that the levels of nursing staff assigned to each nursing station in remote First Nations communities are based on what had been allocated in the past plus increments, rather than on the basis of current needs. We were also told that nurses have been redeployed in crisis situations to provide additional nursing capacity to affected communities.

4.106 In summary. Our review of the available community health plans and levels of nursing staff showed that Health Canada did not take into account the health needs of remote First Nations communities when allocating support.

4.107 Recommendation. When allocating nursing staff levels and other support, Health Canada should work with First Nations communities, and take into account their health needs.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada will work with First Nations communities to better integrate clinical care with culturally appropriate community health planning. This will ensure that Health Canada’s services are further aligned with other health services under the control of the First Nations community.

Health Canada is funding a number of community-based programs that aim to respond to community needs in the areas of mental health, maternal and child health, public health, and home and community care in addition to clinical care. These community-based programs are funded to support community health needs and are most of the time managed by the communities themselves.

The allocation of nursing resources is complex, and depending on the community, different approaches are required. The allocation process takes into account the population size, the geographic location, the accessibility of other health care services, and other specific operational considerations as identified with the communities. As recommended, Health Canada will enhance its practices through the community health planning process.

Health Canada did not compare access to health services in remote First Nations communities to access in other remote communities

4.108 We found that Health Canada did not compare access to clinical and client care services in remote First Nations communities to the access in other remote communities. The Department had not carried out its objective of ensuring that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to the clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations.

4.109 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.110 This finding matters because the objective of Health Canada’s support is to ensure that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to the clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations. The lack of information on whether Health Canada is meeting its objective makes it difficult to hold the Department accountable for the support it provides to remote First Nations individuals or communities.

4.111 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.116.

4.112 What we examined. We examined whether Health Canada had reasonable assurance that First Nations individuals in remote communities had comparable access to the clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations.

4.113 Health Canada’s objective of comparable access. We found that Health Canada had not established specific and measurable criteria for its objective of comparable access to clinical and client care services. Health Canada’s regional officials in Manitoba and Ontario told us that, in these two provinces, they did not have information on whether First Nations had comparable access to the clinical and client care services as other residents living in similar geographic locations.

4.114 We found that the provinces of Manitoba and Ontario provided health services and benefits to residents living in locations geographically similar to remote First Nations communities. In our view, Health Canada could use information about these provincial health services to determine whether remote First Nations have comparable access to the clinical and client care services as other provincial residents. To conduct this analysis, Health Canada would need to work with First Nations communities, provinces, and health service providers.

4.115 The need to measure whether Health Canada provides comparable access was also raised in the Department’s internal audit report in 2010. We are concerned that more than four years after this report, the Department has made little progress in this area.

4.116 Recommendation. Health Canada should work with First Nations communities, provinces, and health service providers to ensure that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada’s priority is to support First Nations communities in receiving health services and benefits that are responsive to their needs and improve their health status.

Health Canada will work with First Nations communities to build health service delivery models for remote and isolated communities, which will better respond to the community’s needs and contribute to ensure First Nations have comparable access to health services.

Coordination of health services among jurisdictions

Committees to resolve interjurisdictional challenges have generally not been effective

4.117 We found that committees comprising representatives of Health Canada and other stakeholders in Manitoba have not proven effective in developing workable solutions to interjurisdictional challenges that negatively affect First Nations individuals’ access to health services. In Ontario, two formal coordinating committees were either recently established or in the process of being established, but it was too early to assess their effectiveness.

4.118 This is important because the lack of coordination among jurisdictions can lead to inefficient delivery of health care services to First Nations individuals and to poorer health outcomes for them. Workable solutions are needed to improve accountability and ensure that individuals in remote First Nations communities have comparable access to health services.

4.119 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

4.120 The responsibility for providing health services to First Nations individuals is shared among federal departments, other levels of government, First Nations organizations and communities, and third-party service providers. According to various reports on First Nations individuals’ access to health services, the failure to clearly delineate the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders has resulted in service gaps, and access problems continued to exist for both federally and provincially funded health services. The reports recognized that effective coordinating mechanisms are needed to identify and resolve these challenges impeding First Nations individuals’ access to health services.

4.121 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.131.

4.122 What we examined. We reviewed documentation to determine whether formal coordinating committees and their working groups in Manitoba and Ontario had identified workable solutions to interjurisdictional challenges negatively affecting First Nations individuals’ access to health services.

4.123 Examples of known but unresolved interjurisdictional challenges included

- lack of integrated health services when First Nations individuals are receiving services both inside and outside their communities,

- difficulties in sharing medical information among health care providers,

- unclear responsibility for funding the transfer of First Nations individuals between medical facilities in Manitoba, and

- unclear responsibility for determining the level and timing of visits from doctors to remote First Nations communities in Manitoba.

4.124 Coordinating mechanisms. Both Manitoba and Ontario had formal committees and working groups in place during our audit.

4.125 In Manitoba, a tripartite senior officials’ committee was established in 2003, as well as several working groups, to

- identify key challenges,

- investigate and inform policy,

- encourage decision makers to act on sustainable strategies and solutions, and

- explore opportunities to ensure First Nations individuals’ health outcomes are comparable to those of other Canadians.

Since the 2003–04 fiscal year, the federal government has provided about $1.8 million to support the work of the senior officials’ committee and its working groups.

4.126 We reviewed the work plans and records of discussions of the senior officials’ committee in Manitoba from January 2013 to June 2014 to assess whether they had identified interjurisdictional challenges and had proposed workable solutions.

4.127 We found that although some draft reports were produced on behalf of the senior officials’ committee in Manitoba, only one report was finalized. We also found no evidence that Health Canada representatives on this committee had recommended workable solutions to interjurisdictional challenges.

4.128 At the end of our audit work, Health Canada officials informed us that recent progress has been made in Manitoba, but results for First Nations individuals had not yet been achieved.

4.129 In Ontario, a tripartite committee at a senior level was established in 2011. This committee was supported by working groups to address options, alternatives, and recommendations for health priorities, which included but were not limited to diabetes and chronic disease prevention and management; mental health and addictions; public health; and data management. According to Health Canada officials, progress has been made in the area of mental health and prescription drug abuse.

4.130 In 2014, another tripartite committee was formed to address health issues in First Nations communities in Northern Ontario. This committee’s priorities are similar to those of the above-mentioned tripartite committee. It was too early to assess the effectiveness of either tripartite committee at the time of our audit.

4.131 Recommendation. Working with First Nations organizations and communities, and the provinces, Health Canada should play a key role in establishing effective coordinating mechanisms with a mandate to respond to priority health issues and related interjurisdictional challenges.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada is committed to working with partners to better coordinate its actions and effective interventions where possible. Health Canada will continue to work with First Nations organizations and communities, and the provinces to explore opportunities for enhanced integration and coordination of health services based on joint priorities. Though these partnerships, due to their multilateral nature, can take time to develop, this should in no way indicate that they are not productive or effective. In fact, experience to date has demonstrated that some of the strongest and most productive relationships require a significant start-up phase to lay the foundation for future collaboration.

Conclusion

4.132 Overall, we concluded that Health Canada did not have reasonable assurance that eligible First Nations individuals living in remote communities in Manitoba and Ontario had access to clinical and client care services and medical transportation benefits as defined for the purpose of this performance audit.

4.133 Nursing stations. We found that Health Canada’s nursing stations were operated with registered nurses, but only one of the nurses in our sample had completed all of the mandatory training courses specified by Health Canada that we selected for review. We also found that Health Canada had not put in place supporting mechanisms to allow nurses to perform some activities outside their legislated scope of practice. We also found that nursing stations had unaddressed health and safety requirements or building code deficiencies. Lastly, we found that Health Canada had not assessed whether each nursing station was capable of providing essential health services or communicated to First Nations individuals what essential services were provided at each nursing station.

4.134 Medical transportation benefits. We found that some First Nations individuals had not registered in the Indian Registration System and were therefore ineligible for Health Canada’s medical transportation benefits. We also found that Health Canada maintained insufficient documentation to demonstrate that medical transportation benefits were administered according to selected principles of Health Canada’s 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework and in compliance with the Treasury Board’s 2009 Directive on Recordkeeping. Lastly, we found that Health Canada was not analyzing the reasons why about 5,000 requests for medical transportation benefits were denied.

4.135 Support allocation and comparable access. We found that Health Canada did not take into account community health needs when allocating its support to remote First Nations communities. We also found that the Department had not implemented its objective of ensuring that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of access to the clinical and client care services and medical transportation benefits for First Nations individuals in remote communities in Manitoba and Ontario to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

The audit objective was to determine whether Health Canada had reasonable assurance that eligible First Nations individuals living in remote communities in Manitoba and Ontario had access to clinical and client care services and medical transportation benefits.

For the purposes of this performance audit, “access” means the following:

- Information about clinical and client care services and medical transportation benefits is readily available and communicated to eligible First Nations individuals.

- Clinical and client care services are available to eligible First Nations individuals and are comparable to those available to other provincial residents in similar geographic locations.

- Clinical and client care services are provided by regulated health professionals who meet registration and licensing requirements of the province in which they practice.

- Medical transportation benefits are available to eligible First Nations individuals who need medically necessary insured health services that are not provided in their community of residence.

Scope and approach

The audit examined the management of Health Canada’s support in Manitoba and Ontario to First Nations individuals’ access to

- health services in remote communities, and

- medical transportation benefits required for accessing health services both inside and outside these communities.

According to Health Canada, there are 25 remote First Nations communities in Manitoba and 29 in Ontario, which represent 64 percent of the 85 remote First Nations communities in Canada.

For the purposes of the audit:

Clinical and client care services consist of

- Urgent care, which involves immediately assessing a patient to determine the severity of a serious illness or injury and the type of care needed. The patient may be given stabilizing treatment and be immediately transported outside the community to a provincial hospital or other facility, or may be kept under observation at the nursing station.

- Non-urgent care, which involves assessing, identifying problems, and generating a case management plan for a patient seeking treatment for a specific, non-life-threatening health concern. This type of care may involve transportation to a facility outside the community.

Medical transportation benefits consist of

- ground, air, and water travel;

- living expenses (meals and accommodations);

- transportation costs for health professionals;

- emergency transportation;

- transportation and living expenses for an escort; and

- transportation to addictions treatment and traditional healers.

The audit included seven First Nations community visits and discussions with representatives from First Nations communities and organizations. We also interviewed provincial officials and officials of professional health organizations to obtain their views and perspectives. However, this report does not comment on their performance.

The audit involved reviewing and analyzing key documents, interviewing department officials, and testing samples of files pertaining to First Nations communities and individuals, health professionals, and agreements.

The audit scope did not include

- a detailed review of the quality of health services and benefits provided to First Nations communities and individuals,

- an assessment of the adequacy of federal resources spent on health services and benefits, and

- a review of health services and benefits provided to Inuit and Métis communities and individuals.

Criteria

To determine whether Health Canada had reasonable assurance that eligible First Nations individuals living in remote communities in Manitoba and Ontario had access to clinical and client care services and medical transportation benefits, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Health Canada has reasonable assurance that information used to determine eligibility for clinical and client care services and medical transportation benefits is reliable. |

|

|

Health Canada has reasonable assurance that information about clinical and client care services and medical transportation benefits is readily available and clearly communicated to eligible First Nations individuals. |

|

|

Health Canada has reasonable assurance that clinical and client care services are available to eligible First Nations individuals and are comparable to those available to other provincial residents in similar geographic locations. |

|

|

Health Canada has reasonable assurance that clinical and client care services are provided by regulated health professionals who meet registration and licensing requirements of the province in which they practice. |

|

|

Health Canada has reasonable assurance that eligible First Nations individuals, who need medically necessary insured health services not provided in their communities of residence, have access to medical transportation benefits. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between April 2013 and December 2014. Audit work for this report was completed on 20 January 2015. The audit involved the examination of material from earlier periods, as required, to gather evidence to conclude against specific criteria.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Ronnie Campbell

Principal: Joe Martire

Director: Ivar Upitis

Julie Hudon

Kathryn Nelson

Mathieu Tremblay

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Nursing stations

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.27 Health Canada should ensure that its nurses working in remote First Nations communities successfully complete the mandatory training courses specified by the Department. (4.18–4.26) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada recognizes that training is very important. Going forward, the Department will strengthen its efforts to meet mandatory training for its nurses and establish processes to monitor compliance and completion rates. One of the challenges in meeting these requirements has been the significant vacancy and turnover rates in nursing. The first order of priority has been to assign adequate levels of nurses in all nursing stations. Health Canada’s Nurse Recruitment and Retention Strategy (October 2013) is striving to augment and stabilize its nursing workforce in efforts to address these shortages. Health Canada will work to balance training needs and service to communities, ensuring that training does not result in a loss of services in a community. |

|

4.37 Health Canada should ensure that its nurses are provided with appropriate supporting mechanisms that allow them to provide essential health services that are outside their legislated scope of practice. (4.28–4.36) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada agrees that nurses need appropriate supporting mechanisms to perform their important duties, and a number of mechanisms are already in place. Health Canada will continue to strengthen and formalize its management and risk control framework for clinical care. Elements of this framework include

|

|

4.53 Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to ensure that nursing stations are inspected on a regular basis and that deficiencies related to health and safety requirements or building codes are addressed in a timely manner. (4.38–4.52) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada will continue to work with First Nations to ensure that buildings are inspected on a regular basis and that deficiencies are addressed in a timely manner. In particular, Health Canada will standardize procedures to ensure facility condition reports are systematically shared with building owners. Health Canada will also make more explicit the requirements and timelines for routine inspections and corresponding repairs, by including relevant requirements in the Health Infrastructure and Capital Protocol. |

|

4.56 Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to ensure that new nursing stations are built according to applicable building codes. (4.38–4.45, 4.54–4.55) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Ensuring buildings are to code is a priority for Health Canada. The Department has a long-standing process that requires an attestation by an architect or engineer to provide assurance that the construction is completed and is compliant with the applicable building codes. To increase clarity going forward, Health Canada will make adjustments to the process to ensure that the scope of this attestation is clear for all parties involved in a construction project. |

|

4.64 Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to ensure that nursing stations are capable of providing Health Canada’s essential health services. (4.57–4.63) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Allocating nursing resources to support the safe, supportive, and culturally appropriate delivery of health services is a priority for Health Canada. In collaboration with First Nations, Health Canada will review the clinical care complement in an effort to progressively move toward the creation of interprofessional teams where possible to support the culturally appropriate, safe, and effective delivery of essential services. |

|

4.65 Health Canada should work with First Nations communities to communicate what services each nursing station provides. (4.57–4.63) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada, in collaboration with First Nations, will provide a list of all clinical care services offered at each nursing station for communication to community members. |

Medical transportation benefits

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.81 Health Canada should work with First Nations communities, and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, to facilitate the registration of First Nations individuals. (4.70–4.80) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada will ensure that information materials about the Indian registration process are available in all nursing stations and will continue to work with partners to improve the availability of information in health facilities. |

|

4.91 Health Canada should maintain sufficient documentation to comply with the Treasury Board’s 2009 Directive on Recordkeeping and to demonstrate that medical transportation benefits are administered according to Health Canada’s 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework. (4.82–4.90) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada’s goal is to ensure that eligible clients receive timely coverage for medical transportation benefits in accordance with the provision of the 2005 Medical Transportation Policy Framework. At the same time, the Department is making efforts to adapt its processes to avoid undue burden on clients and health care professionals. As part of this effort, Health Canada will modify its current guidelines to better align with current operating practices related to the assertion of medical needs and confirmation of attendance. As recommended, Health Canada will disseminate to its staff clear instructions on the processing and retaining of transitional records necessary for the adjudications of benefits. |

Support allocation and comparable access

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.107 When allocating nursing staff levels and other support, Health Canada should work with First Nations communities, and take into account their health needs. (4.96–4.106) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada will work with First Nations communities to better integrate clinical care with culturally appropriate community health planning. This will ensure that Health Canada’s services are further aligned with other health services under the control of the First Nations community. Health Canada is funding a number of community-based programs that aim to respond to community needs in the areas of mental health, maternal and child health, public health, and home and community care in addition to clinical care. These community-based programs are funded to support community health needs and are most of the time managed by the communities themselves. The allocation of nursing resources is complex, and depending on the community, different approaches are required. The allocation process takes into account the population size, the geographic location, the accessibility of other health care services, and other specific operational considerations as identified with the communities. As recommended, Health Canada will enhance its practices through the community health planning process. |

|

4.116 Health Canada should work with First Nations communities, provinces, and health service providers to ensure that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations. (4.108–4.115) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Health Canada’s priority is to support First Nations communities in receiving health services and benefits that are responsive to their needs and improve their health status. Health Canada will work with First Nations communities to build health service delivery models for remote and isolated communities, which will better respond to the community’s needs and contribute to ensure First Nations have comparable access to health services. |

Coordination of health services among jurisdictions

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.131 Working with First Nations organizations and communities, and the provinces, Health Canada should play a key role in establishing effective coordinating mechanisms with a mandate to respond to priority health issues and related interjurisdictional challenges. (4.122–4.130) |