2016 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 3—Preparing Indigenous Offenders for Release—Correctional Service Canada

2016 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of CanadaReport 3—Preparing Indigenous Offenders for Release—Correctional Service Canada

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 3.1—Indigenous offenders make up a growing proportion of offenders in federal custody

- 3.2—Offenders are eligible for conditional release before the ends of their sentences

- 3.3—Indigenous offenders continue to be released more frequently at statutory release than non-Indigenous offenders

- 3.4—Healing Lodges offer a holistic and spiritual approach in accordance with Indigenous values, traditions, and beliefs

- 3.5—The Aboriginal Corrections Continuum of Care model uses a variety of interventions to prepare Indigenous offenders for successful reintegration

- 3.6—Most Indigenous offenders did not complete correctional programs before becoming eligible for parole

- 3.7—In the 2015–16 fiscal year, the number of Indigenous offenders in custody greatly exceeded the capacities of Healing Lodges and Pathways Initiatives

Introduction

Background

3.1 The mission of Correctional Service Canada (CSC) is to “contribute to public safety by actively encouraging and assisting offenders to become law-abiding citizens, while exercising reasonable, safe, secure and humane control.” One of its main legislated responsibilities is to support the successful reintegration of offenders into the community. This involves evaluating an offender’s risk and rehabilitation needs upon admission into custody and providing correctional interventions to mitigate risk throughout the sentence. It also involves assessing an offender’s suitability for parole and developing a plan for his or her successful transition to the community until the end of the sentence.

3.2 The Corrections and Conditional Release Act requires CSC to adopt correctional programs and policies that are responsive to Indigenous offenders’ unique needs. This requires correctional authorities to have a good understanding of Indigenous offenders’ particular circumstances, and to consider culturally appropriate options for rehabilitation in the decision-making process. Offenders in custody who identify as Indigenous (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) differ from the general offender population in several ways. For example, they tend to be younger and more likely to have been convicted of a violent offence.

3.3 For Indigenous offenders admitted into custody in the 2015–16 fiscal year,

- 27 percent were aged 25 or under,

- 64 percent were incarcerated for violent offences,

- 35 percent had served previous sentences,

- 74 percent were serving sentences of four years or less, and

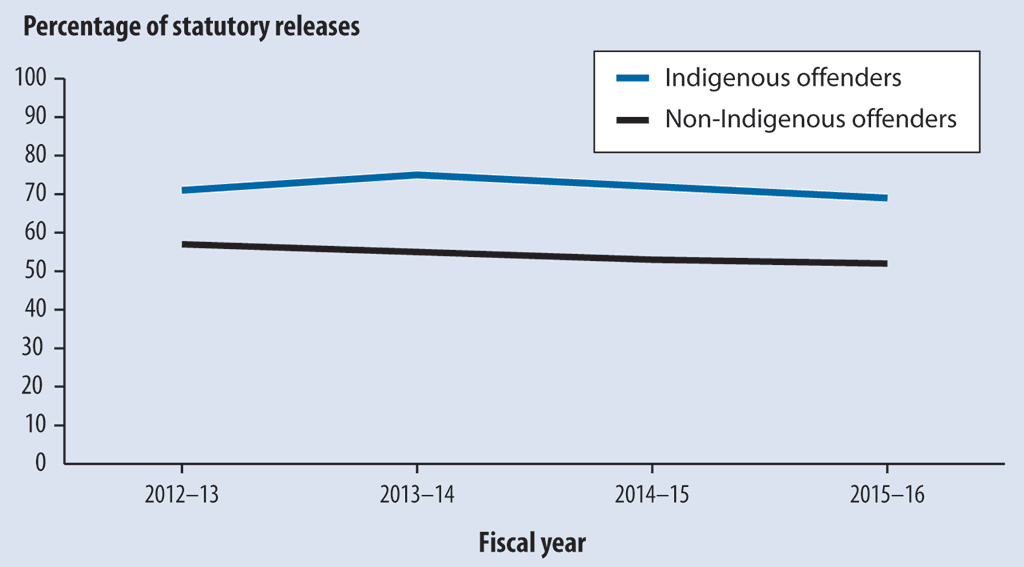

- 89 percent were men and 11 percent were women.

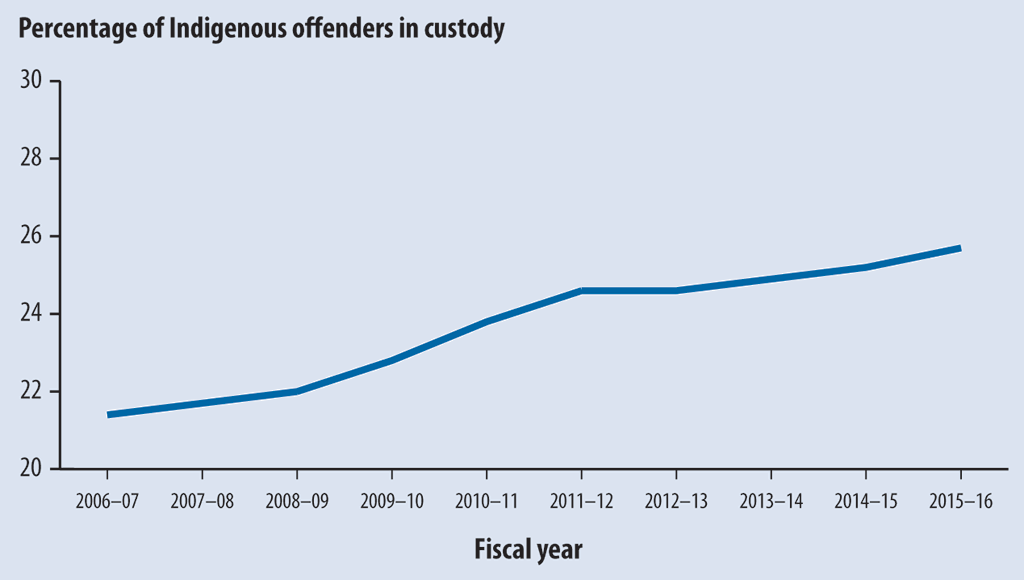

3.4 Indigenous offenders make up a growing and significant proportion of the federal offender population. While Indigenous peoples make up an estimated 3 percent of the Canadian adult population, Indigenous offenders accounted for 26 percent of all offenders in custody in the 2015–16 fiscal year (Exhibit 3.1). In particular, Indigenous women make up 36 percent of female offenders in custody and are the fastest-growing population in the federal correctional system. In the Prairie region, almost half of offenders in custody are Indigenous. The overall population of Indigenous offenders is also growing: From April 2006 to March 2016, the number of Indigenous offenders in custody grew by more than 25 percent, while the number of non-Indigenous offenders in custody declined slightly.

Exhibit 3.1—Indigenous offenders make up a growing proportion of offenders in federal custody

Exhibit 3.1—text version

This is a graphic showing the percentage of Indigenous offenders in federal custody over the last 10 fiscal years.

In the 2006–07 fiscal year, Indigenous offenders were approximately 21 percent of the offenders in custody. This number increased each following fiscal year. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, Indigenous offenders were about 26 percent of the offenders in custody.

| Fiscal year | Population portion |

|---|---|

| 2006–07 | 21.4% |

| 2007–08 | 21.7% |

| 2008–09 | 22.0% |

| 2009–10 | 22.8% |

| 2010–11 | 23.8% |

| 2011–12 | 24.6% |

| 2012–13 | 24.6% |

| 2013–14 | 24.6% |

| 2014–15 | 24.9% |

| 2015–16 | 25.7% |

3.5 CSC has identified the enhancement of correctional interventions for Indigenous offenders as a corporate priority. In 2006, CSC established a Strategic Plan for Aboriginal Corrections to address the specific needs of Indigenous offenders in the correctional system. The Plan included developing culturally specific correctional programs and interventions, and enhancing the cultural competence of staff working with Indigenous offenders. Longer-term objectives involved closing the gap in correctional outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous offenders.

3.6 CSC policies require decisions concerning Indigenous offenders to take into account their unique circumstances, as described in their Aboriginal social history. This history refers to the various circumstances that have affected Indigenous people in Canada, including

- the effects of the Indian Residential Schools system;

- family or community history of suicide, substance abuse, victimization, and fragmentation;

- poverty; and

- loss of or struggle with cultural and spiritual identity.

Culturally appropriate options for rehabilitation must also be considered in the decision-making process.

3.7 The 2015 report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recognized that the criminal convictions of Indigenous offenders frequently resulted from an interplay of many factors, including the intergenerational legacy of residential schools. The report called on the federal government to eliminate the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in custody over the next decade, and to issue detailed annual reports that monitor and evaluate its progress in doing so. It also called for the government to eliminate barriers to the creation of additional Healing Lodges within the federal correctional system. In December 2015, the government committed to implementing all of the Commission’s recommendations. As part of the criminal justice system, CSC has a role to play in addressing recommendations directed toward the successful reintegration of Indigenous offenders in federal custody.

Focus of the audit

3.8 This audit focused on whether Correctional Service Canada provided correctional interventions in a timely manner to Indigenous offenders to assist with their successful reintegration into the community.

3.9 This audit is important because Correctional Service Canada is mandated to provide programs and interventions that are responsive to the unique needs of Indigenous offenders.

3.10 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Releases into the community

Overall message

3.11 Overall, we found that of the Indigenous offenders who were first released from custody to serve the remainder of their sentences in the community in the 2015–16 fiscal year, very few had been released on parole: 69 percent were released at their statutory release dates. Moreover, we found that three quarters of Indigenous offenders who were released at their statutory release dates were released directly into the community from maximum-security (14 percent) and medium-security (65 percent) institutions, limiting their ability to benefit from a gradual release supporting successful reintegration.

3.12 We found that significantly fewer Indigenous offenders were released on parole relative to non-Indigenous offenders. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, 31 percent of Indigenous offenders were released on parole, compared with 48 percent of non-Indigenous offenders.

3.13 These findings are important because Correctional Service Canada is required to support the successful reintegration of offenders into the community. Offenders who have more time to benefit from a gradual and structured release into the community under supervision to the end of their sentences are less likely to reoffend.

3.14 Indigenous offenders make up a significant and growing proportion of offenders in custody. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, Indigenous offenders grew to 26 percent of the total federal offender population (3,513 Indigenous men and 247 Indigenous women of the 14,612 offenders in custody). The Prairie region had the highest proportion of Indigenous offenders, and there were growing numbers in most regions. While there are many factors that contribute to the number of Indigenous offenders in custody, Correctional Service Canada (CSC) can influence the size of the offender population by providing programs and interventions to prepare offenders for conditional release before the end of their sentences.

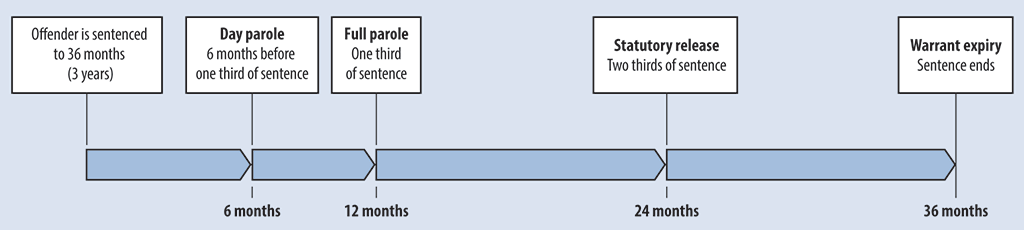

3.15 Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, offenders may be released from a penitentiary to serve the remainder of their sentences under supervision in the community through day parole, full parole, or statutory release (Exhibit 3.2). Parole, or conditional release, is granted by the Parole Board of Canada (Parole Board) and permits offenders to serve the remainder of their sentence in the community under CSC supervision, with specific conditions. If not granted parole, most offenders serving fixed-term sentences are eligible for statutory release after serving two thirds of their sentences in custody.

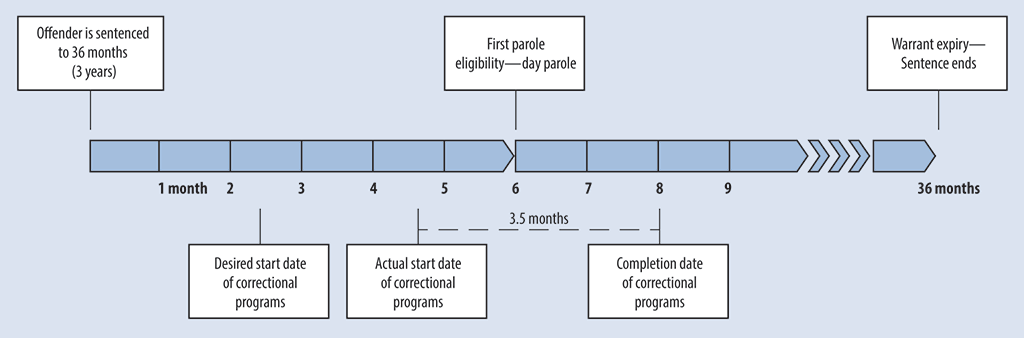

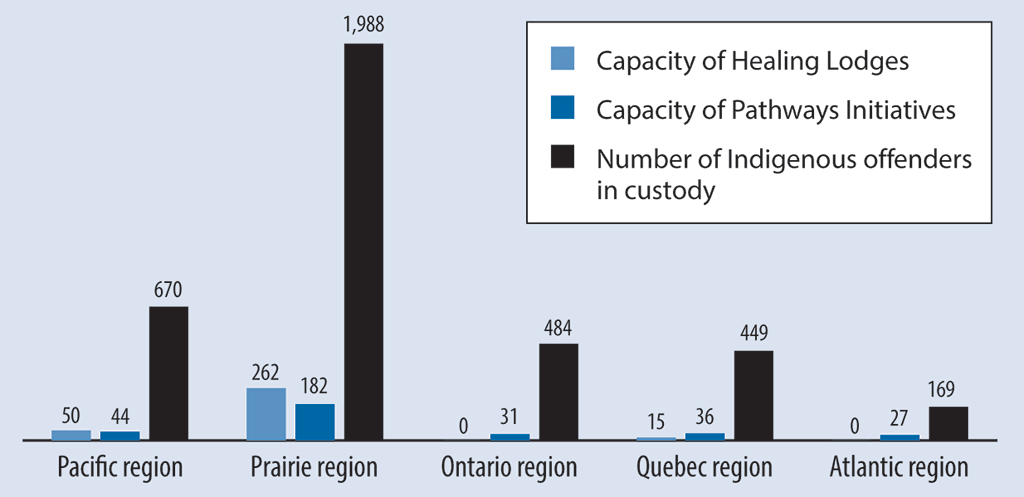

Exhibit 3.2—Offenders are eligible for conditional release before the ends of their sentencesNote *

* Shown for a 3-year sentence, which is the average sentence length for Indigenous offenders admitted into federal custody in the 2015–16 fiscal year, not including life sentences.

Day parole: Day parole is a conditional release that is granted or denied by the Parole Board. Offenders serve the remainder of their sentences under Correctional Service Canada supervision in community facilities.

Full parole: Full parole is a conditional release that is granted or denied by the Parole Board. Offenders serve the remainder of their sentences in locations of their choice in the community, and must report to parole officers or the police.

Statutory release: Statutory release refers to the legal requirement that offenders serving fixed-term sentences must be released after serving two thirds of their sentence in custody, unless found to pose a threat of serious harm or violence.

Warrant expiry: In exceptional circumstances, offenders who pose a threat of serious harm or violence may be held in custody until warrant expiry, when their sentences end.

Exhibit 3.2 graphic—text version

This graphic shows a timeline of when offenders are eligible for different types of release, including conditional release, during a three-year sentence. (Three years is the average sentence length for Indigenous offenders admitted into federal custody in the 2015–16 fiscal year; this does not include life sentences.)

At the start of the timeline, the offender is sentenced to 36 months (or 3 years).

At 6 months before one third of their sentence, offenders are eligible for day parole. Day parole is a conditional release that is granted or denied by the Parole Board. Offenders serve the remainder of their sentences under Correctional Service Canada supervision in community facilities.

At 12 months or one third of their sentence, offenders are eligible for full parole. Full parole is a conditional release that is granted or denied by the Parole Board. Offenders serve the remainder of their sentences in locations of their choice in the community, and must report to parole officers or the police.

At 24 months or two thirds of their sentence, offenders are eligible for statutory release. Statutory release refers to the legal requirement that offenders serving fixed-term sentences must be released after serving two thirds of their sentence in custody, unless found to pose a threat of serious harm or violence.

At 36 months, the warrant expires and the offender’s sentence ends. In exceptional circumstances, offenders who pose a threat of serious harm or violence may be held in custody until warrant expiry, when their sentences end.

3.16 CSC cannot control the number of offenders admitted to its penitentiaries. However, it can influence the length of time that an offender remains in custody, and at what security levels, by providing correctional programs and interventions designed to reduce the offender’s risk to public safety. Rehabilitation efforts while an offender is in custody can also reduce the likelihood that the individual will reoffend after release and be returned into custody.

3.17 CSC assesses whether an offender would be a good candidate for conditional release and provides the assessment information, along with a recommendation, to the Parole Board. Considerations include the offender’s assessed risk to reoffend and the extent to which that risk can be managed in the community. The Parole Board decides whether to grant parole to an offender and sets the conditions of his or her release.

3.18 The timely release of offenders on parole has a direct bearing on public safety: CSC research indicates that offenders released on parole have lower rates of reoffending before their sentences end than do those on statutory release. As well, it also indicates that offenders who have a gradual and structured return to the community under supervision before the end of their sentences are less likely to reoffend.

Most releases of Indigenous offenders were directly from maximum- or medium-security institutions

3.19 We found that in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 69 percent of the 1,066 Indigenous offenders who were released from custody were released at their statutory release dates. This is a significantly higher rate than for non-Indigenous offenders, and it has persisted over several years.

3.20 Of the Indigenous offenders released on statutory release in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 79 percent entered the community directly from maximum- or medium-security institutions.

3.21 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

3.22 This finding matters because CSC can influence the number of Indigenous offenders in custody by ensuring that offenders are prepared for presentation to the Parole Board by their first parole eligibility dates. Moving offenders to lower levels of security while they are still in custody, if appropriate, can also support their successful transition to the community.

3.23 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.27.

3.24 What we examined. We examined when Indigenous offenders were first released from penitentiaries, their type of release, and their level of security over the past three fiscal years.

3.25 Releases by type and level of security. We found that 740 of the 1,066 Indigenous offenders released in the 2015–16 fiscal year (69 percent) were released at their statutory release dates. We found similar rates of statutory release for Indigenous offenders in each of the previous three years; these rates were at persistently higher levels (an average of 18 percent higher) than for non-Indigenous offenders (Exhibit 3.3). As a result, Indigenous offenders served longer portions of their sentences in custody than did non-Indigenous offenders, limiting the time available for them to benefit from a gradual and structured return to the community under supervision to the end of their sentences.

Exhibit 3.3—Indigenous offenders continue to be released more frequently at statutory release than non-Indigenous offenders

Exhibit 3.3—text version

This graphic compares the percentage of Indigenous offenders to the percentage on non-Indigenous offenders who were released at their statutory release dates for each fiscal year between the 2012–13 and the 2015–16 fiscal years. The percentage of Indigenous offenders released at their statutory release dates was higher each fiscal year than for non-Indigenous offenders—an average of 18 percent higher for the four fiscal years.

| Fiscal year | Indigenous offenders | Non-Indigenous offenders |

|---|---|---|

| 2012–13 | 71% | 57% |

| 2013–14 | 75% | 55% |

| 2014–15 | 72% | 53% |

| 2015–16 | 69% | 52% |

3.26 Of the 740 Indigenous offenders released on statutory release in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 102 (14 percent) were released directly into the community from maximum-security institutions, and 483 (65 percent) were released from medium-security institutions. There were similar rates of release from higher-security institutions in each of the previous three years. CSC policy does not require an offender at a higher level of security to be assessed for a possible reduction in security level following a significant event, such as the successful completion of a correctional program. We found that only 13 percent of Indigenous offenders at maximum- and medium-security levels had been assessed for reductions in their security levels after successfully completing a correctional program in the 2015–16 fiscal year.

3.27 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should ensure that Indigenous offenders are assessed for a possible reduction in their security level following a significant event—such as the successful completion of a correctional program—to support their reintegration.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will ensure that each offender’s initial correctional plan clearly outlines the significant events—such as the successful completion of correctional programs and the Pathways Initiative—that will require a reassessment of an offender’s security level and facilitate an offender’s safe transition to lower security and eventual community reintegration. Correctional Service Canada will revise policy as necessary, communicate expectations, and monitor results.

Relatively few Indigenous offenders were released on parole

3.28 We found that significantly fewer Indigenous offenders were released on parole than were non-Indigenous offenders. Of the 1,066 Indigenous offenders released in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 31 percent were released on parole, compared with 48 percent of non-Indigenous offenders. Few Indigenous offenders (12 percent) had their cases prepared for a parole hearing by the time they were first eligible. We also found that 83 percent of Indigenous offenders delayed their parole hearings, reducing the time they could be supervised in the community before their sentences ended.

3.29 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

3.30 This finding matters because parole supervision has consistently proven to be an essential component of offenders’ successful reintegration into the community. The delay or cancellation of parole hearings can reduce the length of time that offenders could benefit from a gradual and structured release into the community before their sentences end; it could also hinder their successful reintegration into the community.

3.31 CSC studies show that offenders granted day or full parole had lower rates of reoffending before their sentences ended than did those released at statutory release. These studies also indicated that most offenders who were assessed as having a low risk of reoffending could be successfully supervised in the community, with a lower likelihood of reoffending before the end of their sentence.

3.32 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.37.

3.33 What we examined. We examined whether CSC ensured that complete and timely reports on Indigenous offenders’ readiness for release were provided to the Parole Board by their first parole eligibility date. We reviewed CSC data on the number of Indigenous offenders released from penitentiaries over the past three fiscal years by security level. We compared the actual release dates to the dates when offenders were first eligible for release.

3.34 Releases on parole. We found that few Indigenous offenders had been prepared for conditional release in a timely manner: 12 percent of the 1,066 Indigenous offenders who were released in the 2015–16 fiscal year had their cases prepared for a parole hearing by their first parole eligibility dates. On average, Indigenous offenders had been prepared for a parole hearing 11 months after the date when they were first eligible, compared with 9 months for non-Indigenous offenders. We also found that fewer Indigenous offenders had been released on parole: 31 percent of Indigenous offenders released from custody in the 2015–16 fiscal year had been granted parole, compared with 48 percent of non-Indigenous offenders.

3.35 Delays or waivers of parole hearings. We found that in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 83 percent of the 1,066 Indigenous offenders released had waived or postponed their parole hearings. Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, offenders have the right to a hearing before the Parole Board at the date they are eligible for full parole. Offenders waive or postpone their hearings for a variety of reasons; one is program non-completion due to CSC’s inability to provide them with timely access to correctional programs to ensure completion by their first parole eligibility date.

3.36 In our sample of 44 case files of Indigenous offenders released in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 40 offenders had waived or postponed their parole hearings. For 25 of these offenders, the inability to complete a correctional program by their parole eligibility date was listed as the reason they waived or postponed their parole hearings. We also found that among low-risk offenders released in the 2015–16 fiscal year, more Indigenous offenders (70 percent) than non-Indigenous offenders (54 percent) had waived or postponed their hearings.

3.37 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should ensure that low-risk Indigenous offenders are prepared for parole hearings when they are first eligible for conditional release.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will ensure that low-risk offenders have timely access to the correctional programs and interventions they require so that their case preparation is complete by the time they are first eligible for conditional release. Correctional Service Canada will further identify specific institutions where the intake assessment process and Aboriginal programming and interventions can be centralized to ensure timely pre-release case preparation.

Access to culturally specific correctional programs and interventions

Overall message

3.38 Overall, we found that Indigenous offenders did not have timely access to Correctional Service Canada’s correctional programs, including those specifically designed to meet their needs. We found that 20 percent of Indigenous offenders were able to complete their correctional programs by the time they were eligible to be considered for conditional release by the Parole Board. We also found that case files did not document how offenders’ participation in Indigenous correctional interventions, such as Healing Lodges or Pathways Initiatives, contributed to their potential for successful reintegration into the community.

3.39 These findings are important because Correctional Service Canada is required under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to provide programs and practices that address the unique needs of Indigenous offenders.

3.40 Correctional Service Canada can help offenders reintegrate successfully by offering correctional programs and interventions, including culturally specific ones. Even minor delays in moving offenders through their assigned correctional programs can lead to delays in parole hearings. Correctional Service Canada’s research indicates that offenders who participate in correctional programs during their time in custody are less likely to reoffend upon release.

3.41 The Corrections and Conditional Release Act requires Correctional Service Canada (CSC) to provide programs designed to address Indigenous offenders’ unique needs. CSC research indicates that participation in culturally specific programs and interventions, preferably delivered by Indigenous people, is a major factor contributing to Indigenous offenders’ success upon release. Culturally specific correctional programs and interventions are part of the Aboriginal Corrections Continuum of Care, which integrates Indigenous culture and spirituality within CSC operations (Exhibit 3.4).

Exhibit 3.4—The Aboriginal Corrections Continuum of Care model uses a variety of interventions to prepare Indigenous offenders for successful reintegration

The Aboriginal Corrections Continuum of Care model starts the path of healing in the institution and engages Indigenous communities to receive offenders upon their release into the community. Interventions included in the model are Aboriginal correctional programs, Healing Lodges, Pathways Initiatives, Elder services, and release plans provided under section 84 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act. The Continuum of Care model

- starts at admission and encourages Indigenous offenders to connect with their culture and communities,

- helps prepare Indigenous offenders for transfer to lower-security custody and for conditional release,

- engages Indigenous communities to receive offenders upon their release into the community and to support offenders’ reintegration, and

- ends with the establishment of community support to sustain offenders’ progress beyond the ends of their sentences and to help prevent reoffending.

Source: Correctional Service Canada

3.42 In general, correctional programs are designed to reduce an offender’s risk of reoffending; they address criminal behaviours, such as violence, substance abuse, and sexual abuse. CSC’s correctional programs for Indigenous offenders include Aboriginal social history considerations, traditional teachings and ceremonies, and cultural activities. CSC has tailored these programs to male and female offenders, as well as Inuit male offenders.

3.43 Alongside the Aboriginal correctional programs, CSC also provides several culturally specific correctional interventions:

- Elder services, whereby CSC contracts with Elders to help meet the spiritual needs of Indigenous offenders within its institutions;

- Healing Lodges, which are correctional institutions that provide traditional healing environments as a method of intervention (Exhibit 3.5);

- Pathways Initiatives, which operate within selected institutions to provide offenders with intensive one-on-one counselling and support, consistent with Indigenous values, traditions, and beliefs; and

- partnerships with Indigenous community groups and organizations in the release planning process and after the offender is released.

Exhibit 3.5—Healing Lodges offer a holistic and spiritual approach in accordance with Indigenous values, traditions, and beliefs

The Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge in Maple Creek, Saskatchewan.

Photo: Correctional Service Canada

Access to culturally specific correctional programs was limited

3.44 We found that Indigenous offenders waited almost five months, on average, to start correctional programs after admission to federal custody. As a result, few Indigenous offenders (20 percent) serving short-term sentences were able to complete their correctional programs by the time they were first eligible for release. We found that offenders completed their correctional programs in about the same amount of time whether they took general or culturally specific programs.

3.45 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- updated correctional programs,

- access to correctional programs, and

- participation in culturally specific correctional programs.

3.46 This finding matters because timely access to correctional programs is important to offenders’ potential for release on parole, so that they can maximize the time spent under supervision in the community. Most Indigenous offenders are serving sentences of four years or less and, on average, are eligible for parole within one year of admission. Furthermore, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act requires CSC to provide programs that are responsive to Indigenous offenders’ unique set of needs.

3.47 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.54.

3.48 What we examined. We examined whether correctional programs were provided to Indigenous offenders by the time they were first eligible for release. We focused on 843 Indigenous offenders who were serving short-term sentences (four years or less) and were released in the 2015–16 fiscal year.

3.49 Updated correctional programs. CSC has developed a range of culturally specific correctional programs for Indigenous offenders and provides them across all regions. CSC recently updated its correctional programs for male offenders and is in the process of rolling them out to all regions by 2017. In doing so, CSC consulted extensively with members of Indigenous communities and corrections experts to ensure that the program content would be effective and culturally relevant. Preliminary evaluations by CSC in the regions where the programs were first piloted indicate that the updated programs are effective in reducing offenders’ likelihood of reoffending while under community supervision. Offenders’ continued success three to five years after the end of a sentence has yet to be assessed. CSC is planning a follow-up evaluation of the outcomes of the correctional programs, including culturally specific correctional programs, in June 2018.

3.50 Access to correctional programs. We found that Indigenous offenders started their correctional programs an average of almost five months after their admission into custody. Early access to correctional programs is particularly important for Indigenous offenders, as about three quarters are serving sentences of four years or less and are eligible for parole within a year of admission. Because it takes an average of 3.5 months to complete correctional programs, the majority of Indigenous offenders would have to start their programs within 2.5 months of admission in order to complete them by their first parole eligibility date (Exhibit 3.6).

Exhibit 3.6—Most Indigenous offenders did not complete correctional programs before becoming eligible for paroleNote *

* Timeline for offenders serving three-year sentences, who are eligible for day parole six months after admission.

Exhibit 3.6—text version

This graphic shows a timeline for offenders serving three-year sentences, who are eligible for day parole six months after admission. It also shows the desired start date, the actual start date, and the completion date of correctional programs.

An offender’s first parole eligibility is day parole at 6 months. Between 4 and 5 months is the actual start date of correctional programs. Correctional programs are completed after 8 months; this means that there are 3.5 months between the actual start date and the completion date. Therefore, between 2 and 3 months into an offender’s sentence is the desired start date of correctional programs to allow offenders to complete their correction programs by their first parole eligibility at 6 months. At 36 months, the warrant expires and an offender’s sentence ends.

3.51 We found that few Indigenous offenders serving short sentences were able to complete their correctional programs by their first parole eligibility dates: Of the Indigenous offenders released into the community in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 20 percent of those who completed correctional programs had done so by their first parole eligibility dates. Indigenous offenders may participate in either general or culturally specific correctional programs. We found that offenders completed their correctional programs in about the same amount of time whether they took general or culturally specific programs.

3.52 Participation in culturally specific correctional programs. We found that about half of Indigenous offenders who participated in correctional programs and were released in the 2015–16 fiscal year took programs specifically designed for Indigenous offenders. In particular, 54 percent of released male offenders and 67 percent of released female offenders had taken culturally specific correctional programs. We found similar results whether offenders were released on parole or at statutory release. CSC officials told us that the small number of Indigenous offenders at some institutions makes it a challenge for CSC to provide timely access to culturally specific correctional programs. Some Indigenous offenders may prefer to take general correctional programs because they are offered more frequently, allowing them to complete their required programming earlier. Others might not be interested in taking a culturally specific correctional program.

3.53 We found that CSC had not examined why Indigenous offenders had taken general correctional programs rather than culturally specific ones, with a view to ensuring sufficient and timely access. Culturally specific correctional programs made up 11 percent of correctional programs provided to offenders and accounted for $8 million of CSC’s correctional program–related expenditures. CSC determined its culturally specific correctional program offerings at each institution on the basis of enrolment levels in previous years and on staff availability rather than on the number of offenders who expressed interest in taking them. As a result, CSC was not able to demonstrate that it had provided Indigenous offenders with sufficient access to culturally specific correctional programs.

3.54 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should ensure that Indigenous offenders have timely access to correctional programs—including culturally specific programs—according to their needs and preferences, to support their successful reintegration.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada has developed an integrated correctional program model for Indigenous offenders, which will be fully implemented next year. Further, Correctional Service Canada will ensure that correctional program resources are aligned with the overall Indigenous offender population need and preference to create timely access to Aboriginal programs. Ongoing monitoring of these initiatives will occur through performance planning and reporting indicators as well as a planned program evaluation.

The impact of culturally specific correctional interventions was not assessed

3.55 We found that access to correctional interventions varied considerably across institutions and regions. We also found that Correctional Service Canada had not examined whether it provided enough access to culturally specific correctional interventions to meet the needs of the Indigenous offender population. As well, offender casework files did not document the impact of the interventions provided to offenders or the extent to which the interventions contributed to the offenders’ successful reintegration into the community.

3.56 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- Elder services,

- Healing Lodges,

- Pathways Initiatives, and

- partnerships with community groups and organizations.

3.57 This finding matters because the Corrections and Conditional Release Act requires Correctional Service Canada to provide correctional interventions that respond to Indigenous offenders’ unique set of needs to support their successful reintegration.

3.58 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.71.

3.59 What we examined. We examined whether CSC provided culturally specific interventions to Indigenous offenders.

3.60 Elder services. CSC engages Elders on contract to provide spiritual counselling and guidance to Indigenous offenders within its institutions, and to deliver culturally specific correctional programs. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, CSC spent $8.2 million in contracting Elder services. Elders also provide CSC staff with an understanding of an offender’s Aboriginal social history to help determine the interventions needed to promote healing.

3.61 We found that CSC did not ensure that its culturally specific correctional programs operated with the required level of Elder involvement, potentially affecting the effectiveness of these programs. CSC policy requires that Elders participate in the delivery of 50 percent of culturally specific correctional programs to reinforce the cultural connection and provide guidance. However, CSC did not have Elders dedicated to the delivery of culturally specific correctional programs at all sites and did not monitor Elder participation. As a result, CSC was not able to demonstrate that programs for Indigenous offenders were delivered as intended.

3.62 Elders also meet with offenders upon request to develop a healing plan, which is documented in an Elder review. Aboriginal liaison officers were required to document Elder reviews and provide information about an offender’s participation in culturally specific interventions. In one third of the offender files we examined, we found that Elder reviews had not been documented. Nor was an offender’s progress in working with an Elder consistently documented. We also found that Aboriginal liaison officers had not received guidance or training on how to evaluate the impact of Elder reviews and interventions on an offender’s progress toward successful reintegration.

3.63 Healing Lodges. CSC funds nine Healing Lodges, two of which are specifically for female offenders. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, these cost $23 million to operate. Five were managed by Indigenous communities or organizations under section 81 of the Act; together, they could accommodate a total of 97 offenders. CSC managed the remaining four Healing Lodges, which had a total capacity of 230 offenders, in close collaboration with Indigenous communities.

3.64 We found that Healing Lodges for male Indigenous offenders operated only at minimum security; however, about 80 percent of male offenders were held in custody at medium- and maximum-security institutions. We also found that all Healing Lodges typically operated at 74 percent of their rated capacity, on average. However, the capacity of Healing Lodges was much lower than the number of Indigenous offenders in every region (Exhibit 3.7). CSC had not assessed the feasibility of expanding Healing Lodges to medium-security for men or to other regions.

Exhibit 3.7—In the 2015–16 fiscal year, the number of Indigenous offenders in custody greatly exceeded the capacities of Healing Lodges and Pathways Initiatives

Exhibit 3.7—text version

This graphic compares the capacities of Healing Lodges and Pathways Initiatives to the number of Indigenous offenders in custody across different regions of Canada in the 2015–16 fiscal year. In all regions, the number of Indigenous offenders exceeded the capacities of Healing Lodges and Pathways Initiatives. But, in the Prairie region, the number of Indigenous offenders exceeded the capacities of those culturally specific interventions by more than four times.

| Region | Healing Lodge capacity | Pathways Initiatives capacity | Number of Indigenous offenders in custody |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific | 50 | 44 | 670 |

| Prairie | 262 | 182 | 1,988 |

| Ontario | 0 | 31 | 484 |

| Quebec | 15 | 36 | 449 |

| Atlantic | 0 | 27 | 169 |

3.65 We also found that, on average, Indigenous offenders who were assessed as having a low risk of reoffending were granted parole from a Healing Lodge at about the same rate as other low-risk Indigenous offenders in minimum-security institutions. However, Indigenous offenders released from Healing Lodges were more likely to successfully complete their supervision (78 percent) than those released from other minimum-security institutions (63 percent).

3.66 Pathways Initiatives. We found that in the 2015–16 fiscal year, Indigenous offenders who participated in Pathways Initiatives at some point during their sentences had higher rates of conditional release than other Indigenous offenders. For example, among the offenders who participated in a Pathways Initiative while in custody and were first released in the 2015–16 fiscal year, 44 percent were released on parole, compared with 25 percent for non-participants. Pathways Initiatives participants were about half as likely to be involved in security incidents as were non-participants, which may have improved their potential for release on parole. However, fewer participants successfully completed their supervision (34 percent) than non-participants (37 percent).

3.67 Offenders who have demonstrated a commitment to their healing paths may participate in Pathways Initiatives. This intervention involves intensive Elder services, including both one-to-one counselling and sharing Indigenous values, traditions, and beliefs. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, CSC operated 26 Pathways Initiatives across 23 institutions, with a total capacity for 320 offenders, at a cost of $4.3 million. Most Pathways Initiatives were offered at a medium security level. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, there were 2,399 Indigenous offenders at a medium security level. In all regions, the capacity of Pathways Initiatives was much lower than the number of Indigenous offenders in custody (Exhibit 3.7).

3.68 CSC recognizes that culturally specific interventions can be effective in supporting the successful reintegration of Indigenous offenders. However, it has yet to develop tools to assess how these interventions contribute to an offender’s progress toward successful reintegration. In our sample of 44 offender case files, we found that the assessments prepared for conditional release by parole officers contained no documentation of the benefits of an offender’s participation in culturally specific correctional interventions, such as Pathways Initiatives or Healing Lodges. Only one assessment provided comments on the offender’s progress in following a healing path.

3.69 Partnerships with community groups and organizations. Under section 84 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, an Indigenous community has the opportunity to propose a release plan when an offender expresses an interest in being released into that community. Indigenous organizations may also participate in the development of these release plans.

3.70 In the 2015–16 fiscal year, we found that 274 offenders were released with a section 84 release plan, up from 143 in the 2011–12 fiscal year. We noted that Indigenous offenders with a section 84 release plan were twice as likely to be granted parole as other Indigenous offenders who applied for parole. Indigenous offenders released in the 2015–16 fiscal year with section 84 release plans were slightly more likely to successfully complete their supervision: 40 percent, compared with 37 percent of Indigenous offenders without such a plan. However, we also noted that parole officers had received little guidance or training on how to prepare a section 84 release plan, potentially limiting its further use.

3.71 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should examine the extent to which Pathways Initiatives and Healing Lodges contribute to the timely and successful release of offenders into the community and how they may be better utilized. Correctional Service Canada should develop guidelines and training for staff working with Indigenous offenders on how to demonstrate the impact of culturally specific interventions on an offender’s progress toward successful reintegration into the community.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will develop structured guidelines to assist case management staff in documenting the impact of culturally specific interventions, such as Pathways Initiatives, in decision-making reports. Further, Correctional Service Canada will ensure the maximum use of Elder services, Pathways Initiatives, and Healing Lodges for those offenders for whom they are most appropriate.

Consideration of an offender’s Aboriginal social history

Overall message

3.72 Overall, we found that Correctional Service Canada staff did not adequately consider Aboriginal social history factors in their case management decisions.

3.73 We also found that the information that Correctional Service Canada staff used to assess Indigenous offenders for their security levels and required correctional programs was limited. Correctional Service Canada had not obtained many of the relevant official documents related to the offenders or their offences before completing the intake assessments.

3.74 We found that, on average, Indigenous offenders were classified at higher security levels, and were more likely to be referred to correctional programs, than non-Indigenous offenders.

3.75 This is important because, to ensure accuracy, Correctional Service Canada is required to use objective and verifiable information to determine an offender’s security level and correctional plan. Moreover, Correctional Service Canada policy requires parole officers to consider an offender’s Aboriginal social history throughout the case management process.

3.76 Upon admission to the federal correctional system, all offenders are assessed for their security levels and rehabilitation needs. Key assessments involved in the intake process include the Custody Rating Scale and the correctional plan. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) is required to consider all relevant available information in completing the intake assessment. This information includes official documents, such as the police report on the offence, pre-sentence reports, and judges’ comments. For an Indigenous offender, an Aboriginal social history (Gladue) report may be available if requested during sentencing. CSC must obtain these official documents from provincial and territorial courts.

3.77 At the time of our audit, CSC used the Custody Rating Scale to determine an Indigenous offender’s security classification, which is a statistically based measure of the security risk an offender poses while inside an institution. CSC also primarily used the Custody Rating Scale to assign correctional programs to Indigenous offenders; however, the scale was not intended for this purpose.

3.78 CSC policy also requires that Aboriginal social history be given due consideration in initial assessments for security classification and correctional program referrals for Indigenous offenders. Furthermore, an Indigenous offender who has shown interest in working with an Elder or in following a traditional healing path can meet with an Elder and have his or her needs assessed and documented in an Elder review.

Administrative delays hindered offender assessments

3.79 We found that Correctional Service Canada had little information available on offenders entering federal penitentiaries. When an offender received a federal sentence, his or her history in the provincial or territorial court system was not automatically forwarded to the federal correctional system. It could take months for Correctional Service Canada to obtain this information from provincial or territorial authorities, delaying assessments and program referrals.

3.80 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

3.81 This finding matters because the assessment of an offender’s risk must be based on objective and verifiable information. With incomplete information, offenders may not be placed at the correct security levels or may not receive appropriate correctional programs to address their criminal risks.

3.82 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.86.

3.83 What we examined. We examined whether CSC obtained the official documents required for completing the offenders’ intake assessments in a timely manner. We reviewed a sample of offender files to determine whether CSC had requested and obtained key official documents to complete intake assessments. We also examined the timeliness of those assessments.

3.84 Information to complete intake assessments. We found that the initial assessments of offenders’ security levels and correctional plans were regularly completed on time, but without the required official documents. CSC policy identifies the key documents that, if available, should be obtained to complete assessments of offenders. In our sample of 45 offender intake assessments completed in the 2015–16 fiscal year, we found that only one file had all the key official documents by the time CSC completed the assessment. Several types of official documents were either not requested or not obtained:

- Police reports. In 5 of the 45 case files, CSC did not obtain police reports on the offender’s current offence. In one of these cases, the police report was not requested.

- Pre-sentence reports. In 10 of the 45 case files, CSC confirmed that the pre-sentence report was not available. It did not obtain pre-sentence reports in 14 other case files. In 11 of these cases, the report was not requested.

- Aboriginal social history report. In 41 of the 45 case files for Indigenous offenders, CSC did not obtain an Aboriginal social history report. While these reports are available only if requested during sentencing proceedings, the files contained no evidence that CSC had requested whether these reports were available.

- Judge’s comments. In 9 of the 45 case files, CSC did not obtain the judge’s comments. In one of these cases, CSC had not requested the judge’s comments.

3.85 We also found that CSC did not update its assessments when requested documents were later obtained.

3.86 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should work with its provincial and territorial partners to ensure that it has timely access to available offender criminal histories and court documents.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will continue to liaise with its territorial and provincial partners to improve timely access to offender criminal histories and court documents.

Assessment tools indicated higher risk for Indigenous offenders

3.87 We found that Indigenous offenders were more likely than non-Indigenous offenders to be classified at higher security levels and referred to correctional programs.

3.88 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

3.89 This finding matters because an offender’s initial security placement affects the security of both offenders and staff, as well as the offender’s potential for parole. Offenders classified at minimum security are more likely to be granted parole by the time they are first eligible for release than are offenders classified at higher levels. Offenders assigned correctional programs are also unlikely to be granted parole before they have successfully completed them.

3.90 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 3.94 and 3.97.

3.91 What we examined. We examined how CSC used the Custody Rating Scale to complete Indigenous offenders’ security classifications and referrals to correctional programming.

3.92 Offender security levels. We found that greater proportions of Indigenous offenders were classified at maximum- and medium-security levels upon admission than were non-Indigenous offenders. For each offender admitted into custody, corrections staff used the Custody Rating Scale and applied their professional judgment to determine the offender’s security level. For the 1,100 Indigenous offenders admitted into custody in the 2015–16 fiscal year:

- 16 percent were classified at a maximum-security level upon admission, compared with 11 percent of non-Indigenous offenders;

- 61 percent were classified at a medium-security level, compared with 47 percent of non-Indigenous offenders; and

- 23 percent were classified at a minimum-security level, compared with 42 percent of non-Indigenous offenders.

We found similar rates among male and female Indigenous offenders, and in each of the previous three fiscal years.

3.93 CSC examined the use of the Custody Rating Scale with Indigenous male and female offenders, and found that it was a valid and appropriate tool to determine an offender’s initial security classification, in conjunction with the professional judgment of staff. However, CSC research has also pointed to the potential value of additional measures to better address the unique risks of Indigenous offenders. We found that the scale does not include the consideration of Aboriginal social history factors. We also found that in applying their professional judgment in the determination of an Indigenous offender’s security level, staff were not provided with guidance on how to consider an offender’s social history appropriately.

3.94 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should explore additional tools and processes to assess the security classification of Indigenous offenders, including the development of structured guidance for the consideration of an offender’s Aboriginal social history.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will continue to conduct research on the validity of its current assessment tools with regard to Indigenous offenders. It will also examine the need for and feasibility of developing new culturally appropriate assessment measures founded on the Gladue principles.

3.95 Referrals to correctional programs. We found that the primary tool that CSC used to refer Indigenous offenders to correctional programs was the Custody Rating Scale. However, the Custody Rating Scale was designed as a security classification tool, not a program referral tool, and could lead to higher-than-necessary referrals to correctional programs. For example, 81 percent of Indigenous offenders released in the 2015–16 fiscal year had been referred to programs, compared with 60 percent of non-Indigenous offenders.

3.96 CSC uses a different tool, the Statistical Information on Recidivism (SIR-R1) scale, to refer non-Indigenous male offenders to correctional programs. Recent CSC research has found that a modified version of this tool is appropriate for use with Indigenous offenders and would result in more accurate assessments of the need for correctional programs. As well, CSC has been developing the Criminal Risk Index to be a more appropriate actuarial tool for the assignment of Indigenous offenders to correctional programs. However, by the end of the audit period, CSC continued to use the Custody Rating Scale to refer Indigenous offenders to correctional programs.

3.97 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should use the most appropriate assessment tools available to refer Indigenous offenders to correctional programs.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada has developed and will be implementing the Criminal Risk Index, a more appropriate actuarial tool for the assignment of Indigenous offenders to correctional programs.

Consideration of Aboriginal social history was insufficient

3.98 We found that Correctional Service Canada did not provide staff with sufficient guidance and training on how to consider an offender’s Aboriginal social history in case management decisions. We found that staff did not document their consideration of an offender’s Aboriginal social history in their assessments for conditional release.

3.99 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

3.100 This finding matters because CSC policy requires that unique systemic or background factors that may have influenced Indigenous offenders’ lives be considered in all case management decisions involving Indigenous offenders. Without proper documentation of how this information is considered, CSC did not meet its own requirements for Indigenous offenders.

3.101 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.106.

3.102 What we examined. We examined whether CSC provided sufficient guidance and training to its staff on how to consider Aboriginal social history in their case management decisions.

3.103 Guidance and training. We found that CSC staff had not received sufficient guidance or training on how to consider Aboriginal social history in their assessments.

3.104 For example, CSC policy requires a parole officer to consider an offender’s Aboriginal social history in an assessment for parole eligibility. However, the policy does not specify how these assessments are to be made. Moreover, our review of 44 Indigenous offender case files found that the consideration of offenders’ social history was not documented in CSC’s assessments for conditional release prepared for the Parole Board.

3.105 We also found that the training provided to parole officers on how to apply offenders’ Aboriginal social history in case management decisions was limited. For example, most of CSC’s 1,300 parole officers were given two days of training on Aboriginal social history in 2013. Since then, 57 newly hired parole officers have been provided about six hours of training on Aboriginal social history during their orientation. CSC has recognized the need to include more comprehensive training on Aboriginal social history in its case management training programs.

3.106 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should develop structured guidance to support the consideration of Aboriginal social history factors in case management decisions. It should then ensure that staff are adequately trained on how to consider Aboriginal social history in case management decisions.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Building on existing training initiatives, Correctional Service Canada will continue to integrate Aboriginal social history considerations into case management training and practices.

Conclusion

3.107 We concluded that Correctional Service Canada provided correctional programs to Indigenous offenders to assist with their rehabilitation and successful reintegration into the community, but did not do so in a timely manner. Correctional Service Canada staff did not adequately define or document how offenders’ participation in culturally specific correctional interventions contributed to their potential for successful reintegration into the community. As well, staff was not provided with sufficient guidance or training on how to apply Aboriginal social history factors in case management decisions.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of Correctional Service Canada’s reintegration activities, to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether Correctional Service Canada provided correctional interventions in a timely manner, and assessed their performance, to assist the successful reintegration of Indigenous offenders into the community.

Scope and approach

We reviewed the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and relevant Commissioner’s Directives for Indigenous offenders, including procedures relating to intake assessment, correctional interventions, and pre-release decision making.

We analyzed data extracted from Correctional Service Canada’s Offender Management System to identify dates of first release by day parole, full parole, and statutory release. We compared those with dates when Indigenous offenders were first eligible. Our data included all Indigenous offenders first released from custody during the 2011–12 through 2015–16 fiscal years. We assessed the quality of CSC data and found it sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our analysis.

Our work included reviewing the Offender Management System database records of 45 Indigenous offenders admitted into CSC custody on new sentences of four years or less during the last three months of 2015. The files were selected to ensure that the sample was proportional to the overall population with regard to admission type, geographical region, gender, and risk level. The files were also selected to determine whether CSC was following procedures when completing required intake assessments. We also analyzed the Offender Management System database records of 44 Indigenous offenders serving sentences of four years or less released from CSC custody during the last three months of 2015. The files were selected to ensure that the sample was proportional to the overall population with regard to geographical region, gender, and risk level. The files were also selected to identify the correctional interventions delivered to offenders and the timing of their release preparations.

For certain audit tests, results were based on probability sampling. Where probability sampling was used, sample sizes were sufficient to report on the sampled population with a confidence level of 90 percent and a margin of error of +10 percent.

Criteria

To determine whether Correctional Service Canada (CSC) provided correctional interventions in a timely manner, and assessed their performance, to assist the successful reintegration of Indigenous offenders into the community, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Correctional Service Canada has the information it needs to complete intake assessments and correctional plans for Indigenous offenders in a timely manner. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada ensures that its tools to complete intake assessments and correctional plans are appropriate for the unique needs of Indigenous offenders. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada has trained and qualified staff to complete the intake assessments and correctional plans for Indigenous offenders. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada provides correctional interventions designed to address the needs of Indigenous offenders. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada provides correctional interventions to Indigenous offenders in a timely manner. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada has trained and qualified staff to provide correctional interventions to Indigenous offenders. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada ensures that complete and timely reports are provided to the Parole Board of Canada at the first parole eligibility date. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada has trained and qualified staff to prepare release assessments of Indigenous offenders for the Parole Board of Canada. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between April 2013 and August 2016. Audit work for this report was completed on 23 July 2016. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of the audit.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Nancy Cheng

Principal: Frank Barrett

Director: Carol McCalla

Donna Ardelean

Daniele Bozzelli

Theresa Crossan

Marie-Claude Dionne

Jenna Lindley

Catherine Martin

Francis Michaud

Crystal St-Denis

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Releases into the community

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.27 Correctional Service Canada should ensure that Indigenous offenders are assessed for a possible reduction in their security level following a significant event—such as the successful completion of a correctional program—to support their reintegration. (3.19–3.26) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will ensure that each offender’s initial correctional plan clearly outlines the significant events—such as the successful completion of correctional programs and the Pathways Initiative—that will require a reassessment of an offender’s security level and facilitate an offender’s safe transition to lower security and eventual community reintegration. Correctional Service Canada will revise policy as necessary, communicate expectations, and monitor results. |

|

3.37 Correctional Service Canada should ensure that low-risk Indigenous offenders are prepared for parole hearings when they are first eligible for conditional release. (3.28–3.36) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will ensure that low-risk offenders have timely access to the correctional programs and interventions they require so that their case preparation is complete by the time they are first eligible for conditional release. Correctional Service Canada will further identify specific institutions where the intake assessment process and Aboriginal programming and interventions can be centralized to ensure timely pre-release case preparation. |

Access to culturally specific correctional programs and interventions

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.54 Correctional Service Canada should ensure that Indigenous offenders have timely access to correctional programs—including culturally specific programs—according to their needs and preferences, to support their successful reintegration. (3.44–3.53) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada has developed an integrated correctional program model for Indigenous offenders, which will be fully implemented next year. Further, Correctional Service Canada will ensure that correctional program resources are aligned with the overall Indigenous offender population need and preference to create timely access to Aboriginal programs. Ongoing monitoring of these initiatives will occur through performance planning and reporting indicators as well as a planned program evaluation. |

|

3.71 Correctional Service Canada should examine the extent to which Pathways Initiatives and Healing Lodges contribute to the timely and successful release of offenders into the community and how they may be better utilized. Correctional Service Canada should develop guidelines and training for staff working with Indigenous offenders on how to demonstrate the impact of culturally specific interventions on an offender’s progress toward successful reintegration into the community. (3.55–3.70) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will develop structured guidelines to assist case management staff in documenting the impact of culturally specific interventions, such as Pathways Initiatives, in decision-making reports. Further, Correctional Service Canada will ensure the maximum use of Elder services, Pathways Initiatives, and Healing Lodges for those offenders for whom they are most appropriate. |

Consideration of an offender’s Aboriginal social history

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.86 Correctional Service Canada should work with its provincial and territorial partners to ensure that it has timely access to available offender criminal histories and court documents. (3.79–3.85) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will continue to liaise with its territorial and provincial partners to improve timely access to offender criminal histories and court documents. |

|

3.94 Correctional Service Canada should explore additional tools and processes to assess the security classification of Indigenous offenders, including the development of structured guidance for the consideration of an offender’s Aboriginal social history. (3.92–3.93) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will continue to conduct research on the validity of its current assessment tools with regard to Indigenous offenders. It will also examine the need for and feasibility of developing new culturally appropriate assessment measures founded on the Gladue principles. |

|

3.97 Correctional Service Canada should use the most appropriate assessment tools available to refer Indigenous offenders to correctional programs. (3.95–3.96) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada has developed and will be implementing the Criminal Risk Index, a more appropriate actuarial tool for the assignment of Indigenous offenders to correctional programs. |

|

3.106 Correctional Service Canada should develop structured guidance to support the consideration of Aboriginal social history factors in case management decisions. It should then ensure that staff are adequately trained on how to consider Aboriginal social history in case management decisions. (3.98–3.105) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Building on existing training initiatives, Correctional Service Canada will continue to integrate Aboriginal social history considerations into case management training and practices. |