Commentary on the 2015–2016 Financial Audits Commentary on the 2015–2016 Financial Audits

Commentary on the 2015–2016 Financial Audits

Background to the Commentaries on Financial Audits

Message from the Auditor General of Canada

I am pleased to present this first report derived from the link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial audits that the Office of the Auditor General of Canada conducts every year within federal departments and organizations. This new report is not an audit, but rather a commentary stemming from the work we do as financial auditors. We intend to produce it every year.

Financial audits account for close to half of the Office’s workload. For the 2015–16 fiscal year, the Office audited 69 federal link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial statements, at a cost of $29 million of its planned annual spending. These audits included the audit of the financial statements of the government as a whole, found in the Public Accounts of Canada. Combined, our financial audits covered assets of $1.2 trillion and liabilities of $1.5 trillion.

This year, our commentary focuses on the critical role of financial reports as accountability documents providing elected officials and Canadians with information about the use of public funds and the health of the government’s finances. Communicating this information is important because it helps the government make better policy decisions such as setting taxes and providing more sustainable services to Canadians. The credibility and transparency of financial reports are crucial, and our financial audits add to them.

The government’s financial statements in the Public Accounts of Canada are highly summarized. As a result, some important information relevant to parliamentary oversight may not be readily visible, especially for Crown corporations. It is therefore important to consider information from additional sources to get a full picture of the health of the government’s finances.

In addition, financial statements include not only hard numbers, but also estimated amounts. These estimates can vary significantly depending on the assumptions selected by the government to develop them. Understanding the impact of estimates on the financial statements and the underlying sensitivities is therefore important to ensure effective parliamentary oversight over the government’s finances.

The federal public sector and the hundreds of financial reports it produces each year are complex. Understanding this information is not always easy, particularly for non-specialists, for a number of reasons. These reasons include the sheer volume of information that is produced, where it resides, and how it is presented.

Our financial audits play a crucial role in supporting the accountability relationship between Parliament and government organizations who spend taxpayer dollars to deliver programs and services to Canadians. This accountability helps to ensure that the spending of taxpayer dollars serves the best interests of all Canadians.

Credible and transparent financial information is the cornerstone of accountability. It is my hope that this report will start and sustain a conversation on this important topic in coming years.

About this report

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada is presenting this report to Parliament and Canadians to

- highlight the importance of providing credible, transparent, and easy-to-understand financial information to those individuals whose job it is to oversee the government’s finances;

- provide clear and concise information about the scope and complexity of the federal financial audits the Office performs each year; and

- provide commentary on any issues of note identified during the most recent financial audits.

Understanding financial information

Financial information is abundant

Globally in the public and private sectors, preparers and users of financial reports are concerned that not all information reported is clear and accessible. Generic language, too much information, insignificant information, and increasingly demanding financial reporting requirements imposed by standard setters and regulators often make information less accessible than it might otherwise be. Information overload can harm the clarity and usefulness of financial reports.

Canada’s financial information is no exception. The annual reports produced by the 69 entities we audit (including the Public Accounts of Canada) contain more than 7,000 pages, of which more than one third are the financial statements and the link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial statements discussion and analysis.

To support effective Parliamentary oversight of government finances, information must be relevant, clearly articulated, and presented in a way that makes its importance easy to understand. It must also be easy to navigate. By following these criteria, government officials help ensure that parliamentarians and other readers can easily identify the information that is relevant to their needs. Government officials are responsible for making sure that the information they provide is relevant, easy to access, and easy to understand.

Financial information can be hard to find

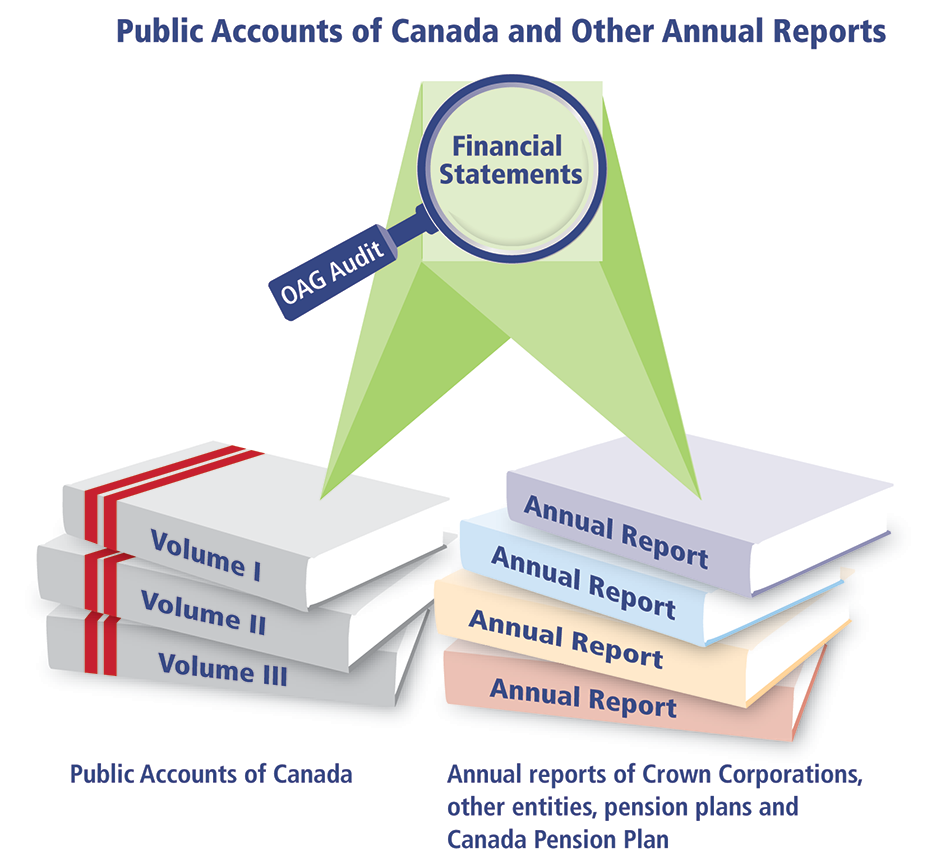

The Public Accounts of Canada is a thick report consisting of three volumes. The financial statements and the financial statements discussion and analysis are found in the two first sections of Volume I, and together they form the government’s main accountability report.

The government’s financial statements presented in the Public Accounts of Canada are highly summarized. The Office’s audit of the government’s financial statements does not cover information found elsewhere in the Public Accounts of Canada.

Text version

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada audits financial statements, which are found in the Public Accounts of Canada, and in the annual reports of Crown Corporations, other entities, pension plans, and the Canada Pension Plan.

The Public Accounts of Canada are also packed with supplementary detailed information and analyses that are often required by legislation. This information, however, is not always enough to depict certain significant events or transactions. Information presented in other documents is also useful, therefore, for understanding the health of the government’s finances. Parliamentarians and other interested readers must look beyond the Public Accounts of Canada.

Annual reports and the accompanying financial statements often contain useful information that is not directly shown in the Public Accounts of Canada. For example, in the annual reports of individual organizations, readers will find detailed information about significant events or transactions that may have affected the organization’s bottom line. To understand the full picture of the federal government’s finances, one must often piece together information from different sources.

Crown corporations publish their annual reports, which contain their financial statements, on their websites. In the case of government departments, the annual report is called a departmental performance report. Departmental performance reports are made available by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and on the respective departmental websites.

The reports need to be relevant, transparent, and easy to understand if they are to be useful in holding individual organizations accountable for the way they manage their activities and spend taxpayer dollars. Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada promotes such quality with its Awards of Excellence in Corporate Reporting, which includes two federal Crown corporation categories. Each year, one small and one large federal Crown corporation receives this award. Export Development Canada, Defence Construction Canada, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and Telefilm Canada were recipients in 2014 and 2015.

Crown corporations’ financial visibility is limited within the Public Accounts of Canada, yet they account for a significant portion of government activity.

As of 31 December 2016, the Office audited 42 Crown corporations, which employed over 90,000 staff. Of these 42 Crown corporations, 27 depend on government funding, and the other 15 support themselves by selling goods and services on the open market. These 15 commercial Crown corporations are known as enterprise Crown corporations, which are a type of government business enterprise (GBE).

The financial information on GBEs is not always visibly reported in the Public Accounts of Canada. For example, the government’s 2015–16 financial statements in the Public Accounts of Canada recorded a $91 billion net investment in the GBEs. However, this net figure does not convey the true magnitude of the $485 billion in GBE assets, the $442 billion in GBE liabilities, or the $48 billion in loans and advances made by the government to the GBEs. While the presentation of a net figure complies with accounting standards, and while the amounts of assets and liabilities are available in supporting tables included elsewhere in the Public Accounts of Canada, a net figure does not provide insight about the events or transactions that may be of interest to parliamentarians.

For example, both Ridley Terminals IncorporatedInc. and the Royal Canadian Mint reported in their December 2015 financial statements unusual losses in connection with certain capital assets totalling, on a combined basis, $165 million. These losses resulted from adverse circumstances that led to a reduction in the ability of certain capital assets to generate future revenues.

These losses were significant for the Crown corporations involved: they represented one third of the net value of Ridley Terminals Inc.’s capital assets, and one quarter of the Royal Canadian Mint’s. Though the losses were appropriately disclosed and discussed in each corporation’s public annual report, because of their relatively small size compared to the finances of the government as a whole, they were not visible in the Public Accounts of Canada, either in the government’s financial statements or in the financial statements discussion and analysis. In other words, anyone looking just at the Public Accounts of Canada would have no sight of these losses.

These losses are only one example of relevant transactions or events that can be highlighted in the government’s summarized financial reports. Doing so allows elected officials to ask questions and exercise adequate oversight over resource decisions made within the enterprise Crown corporation sector.

Financial information can be difficult to understand

Financial statements report numbers. But numbers alone are not enough to give readers a sense of an organization’s or a government’s overall financial health and prospects. This is the reason that narrative explanations, in the form of a financial statements discussion and analysis (FSDA), are included with the financial statements.

The FSDA helps those with oversight responsibilities make informed decisions by providing additional information and context about the government’s or an organization’s annual results and financial position. This additional information helps clarify important relationships between the numbers in the financial statements. These relationships are shown through graphics, key financial indicators, variances in amounts compared with budgets and previous years, and analyses of historical trends.

It is not enough for the FSDA to explain how planned results were achieved or not and to provide expectations about the future. It should also elaborate on the government’s ability to sustain its activities and fulfill its obligations, and on the risks that may threaten this ability. It should present a balanced discussion of negative and positive results and link financial results to strategic outcomes.

In Canada, best practices have been developed for the preparation of the FSDA by governments, and for the preparation of similar analyses by commercial corporations, such as the enterprise Crown corporations. These best practices help maximize the usefulness of the FSDA.

While the government’s 2015–16 financial statements discussion and analysis (FSDA) includes the main elements of best practices referenced above, there is opportunity to improve its usefulness for elected officials.

An example of a possible improvement would be enhanced reporting of the physical condition and stewardship of the government’s capital assets. These physical assets include lands, buildings, equipment, and vehicles. These assets are valuable—they had a net value of $66 billion as of 31 March 2016—and they are key to the government’s ability to deliver programs and services to Canadians.

Reporting on the physical condition and the stewardship of capital assets provides important accountability information to help elected officials assess how and when capital assets need to be renewed or replaced. It would also help them assess whether sufficient funding will be available to meet these needs and to ensure the sustainability of program and service delivery.

Currently, the FSDA offers limited insights on capital assets. It reports that 60 percent of the original cost of the government’s capital assets had been amortized or consumed as of 31 March 2016. Additional useful insights could include an explanation of why the value of capital assets has changed over the recent years; a description of future plans to renew aging infrastructure; and the highlighting of significant transactions and events by major category, including those of enterprise Crown corporations.

Financial ratios can help to communicate and interpret financial information and historical trends. For example, Canadian best practices suggest to use the “net book value of capital assets to cost of capital assets” ratio. For the past three years, this ratio has been roughly 46 percent for the government as a whole, meaning that on average the government’s physical assets have gone through more than half of their useful lives. This ratio can support a discussion on future capital asset needs and the plans in place to address these needs. Such analysis would help elected officials engage in a useful discussion with government officials.

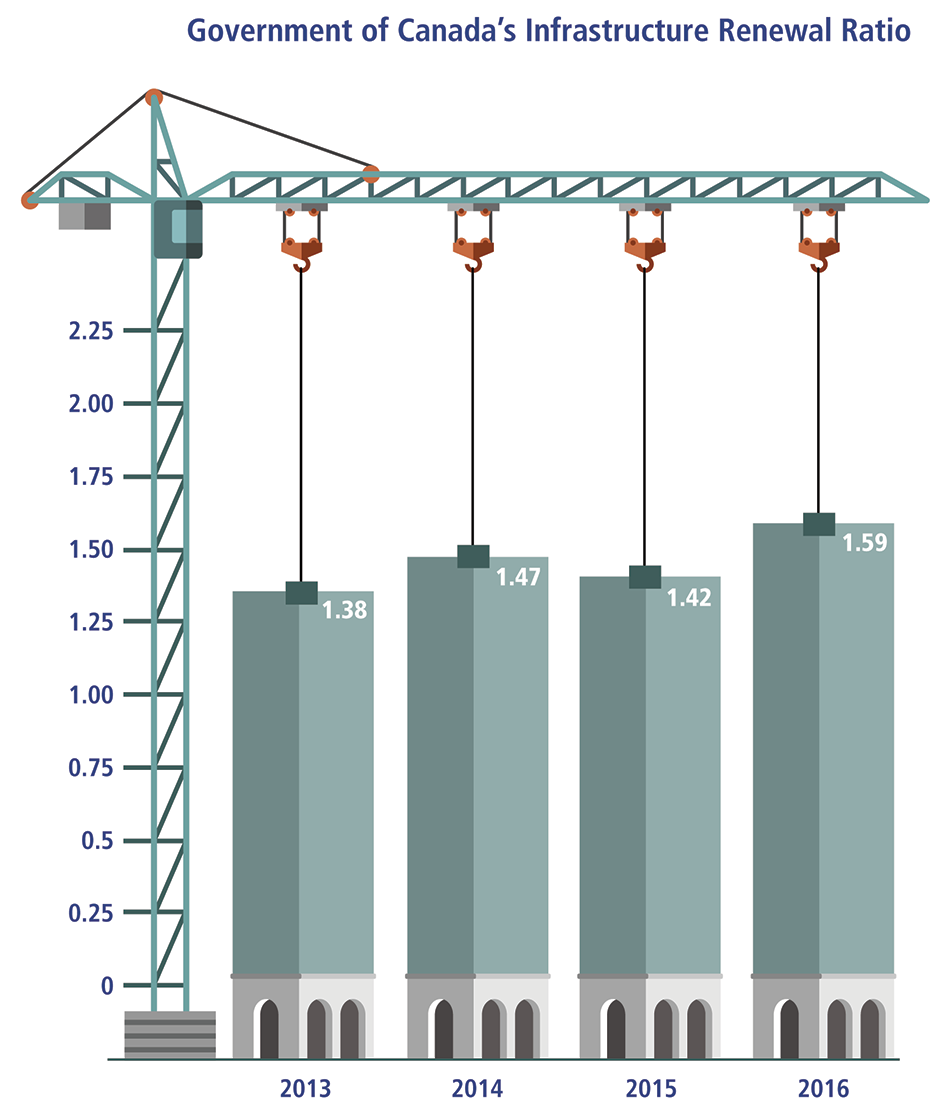

Another example is the infrastructure renewal ratio, which is used in other jurisdictions. It is the rate at which infrastructure is being replaced or increased, or both, compared with the rate at which it is being used up. For the Government of Canada, this ratio has grown to about 1.6 in recent years, meaning that the government is investing in infrastructure. This is another insight that can help elected officials to engage government officials in a conversation about infrastructure investment.

Text version

Government of Canada’s Infrastructure Renewal Ratio

| Year | Ratio |

|---|---|

| 2013 | 1.38 |

| 2014 | 1.47 |

| 2015 | 1.42 |

| 2016 | 1.59 |

We encourage the government to consider enhancing its reporting on the condition of capital assets.

A number of Canadian sources have published useful guidance to help readers understand government financial reports, including the following:

- Understanding Canadian Public Sector Financial Statements, by the Auditor General of British Columbia (June 2014)

- Reading financial statements: What do I need to know? frequently asked questionsFAQ, by Chartered Professional Accountants of CanadaCPA Canada (2014)

- link to a portable document format (PDF) file20 Questions about Government Financial Reporting, by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (now CPA Canada) (2003).

These documents are a good starting point for elected officials interested in ensuring the effectiveness of their oversight.

Financial statements involve significant judgments and estimates

Preparing financial statements is not an exact science. Accounting standards are complex and nuanced, reflecting the nature of the transactions they are designed to capture. As such, those preparing financial statements must often make significant judgments.

Another factor that makes financial statements challenging to understand is that they include estimates. Estimates are necessary to reflect both current economic conditions and future expectations when measuring assets and liabilities. In developing estimates, management uses a wide range of assumptions to capture the uncertainty of the amounts recorded in the financial statements.

The challenge is that estimates used in financial statements are inherently sensitive to changes in the assumptions used to develop them. There is a direct link between the reasonableness of estimates and the quality of the financial information that is being produced to inform decision making. Given the significant impact of estimates on financial statements, it is important that elected officials closely monitor these estimates and regularly challenge management about the validity of the underlying assumptions and the adequacy of the complex models and methods used to build the estimates.

Note 1 in the government’s financial statements provides useful information about the uncertainty involved in preparing the financial statements, including the nature of the estimates and the significant judgments made by management. Similar notes are found in the financial statements of individual organizations.

There are many examples of significant management estimates in the financial statements of the government and federal Crown corporations. By far, the most significant one relates to the government’s liability for public sector pensions and other future benefits, which totalled $237.9 billion as of 31 March 2016. Other examples include

- the government’s long-term environmental liabilities of $13.3 billion;

- provisions for potential losses that could result from loans that are ultimately not repaid (for example, in relation to loans, loan commitments and loan guarantees issued by Export Development Canada for $1.9 billion); and

- provisions for potential losses that may result from claims by third parties (for example, a provision of $708 million recorded by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation in relation to total outstanding insured mortgage loans totalling $526 billion).

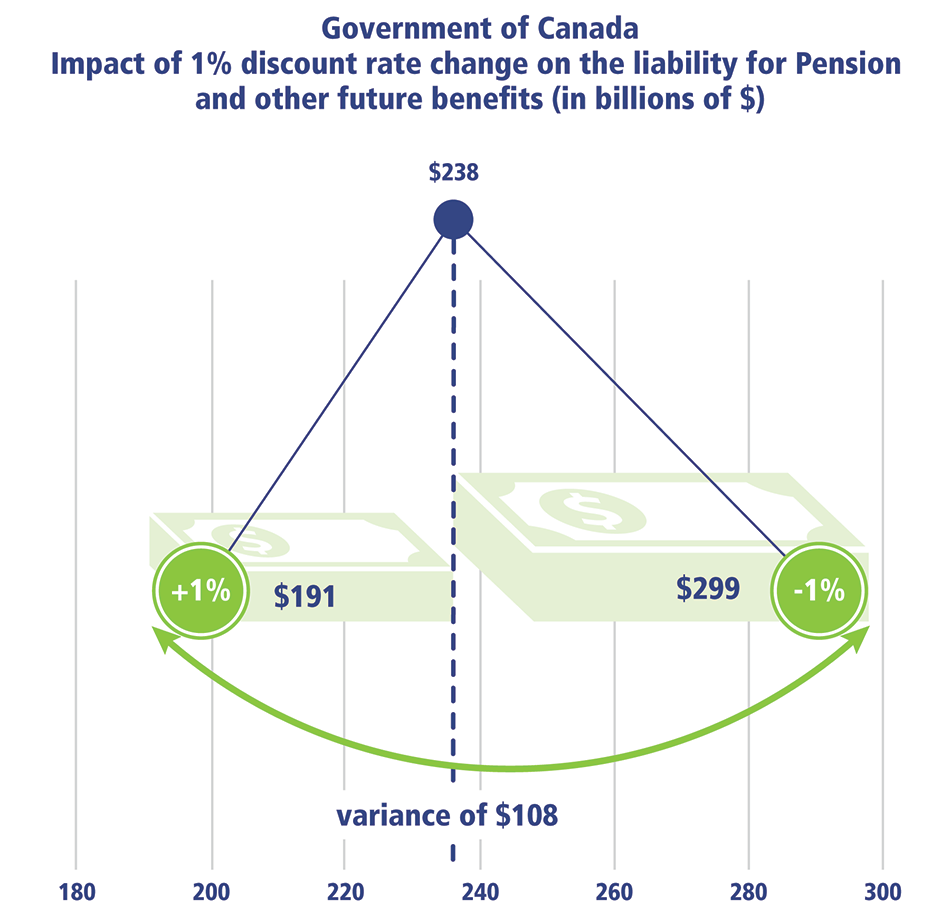

Financial statements often include several long-term assets and liabilities reflecting the future collection or payment of cash over multiple years. The discount rate is an important assumption. It is an interest rate that is used to calculate the current value of these long-term assets or liabilities.

Financial statements include important information on the sensitivity of changes in the discount rate and other assumptions used to calculate accounting estimates. It is important for elected officials to know where to find these sensitivities in the financial statements. With this information, they can challenge the government and individual organizations on the reasonableness of the assumptions used to develop the estimates.

Understanding the extent to which the discount rate is sensitive provides a number of insights. For example, potential future adverse changes in interest rates may result in increased costs and affect the government entity’s ability to deliver programs.

Canada Post provides a real-life illustration of this sensitivity. In its December 2015 financial statements, the Corporation reported that a potential decrease of 50 basis points in the discount rate could result in a $2.5 billion increase in its pension and other benefit liabilities. This assumption became a reality in 2016, when market rates fell significantly. The drop in rates was the main driver behind the $3.4 billion increase in pension and other benefit liabilities which the Corporation reported in its third-quarter financial statements. These fluctuations in discount rates have resulted in sizable financial and long-term liquidity risks to the Corporation.

This chart shows that the government’s liability for pension and other future benefits recorded as of 31 March 2016 could vary within a range of over $100 billion if the discount rate increased or decreased by up to one percentage point.

Source: Public Accounts of Canada, 31 March 2016

Text version

Government of Canada—Impact of 1% discount rate change on the liability for Pension and other future benefits (in billions of dollars)

Starting value: $238

Change of rate: +1%

Value: $191

Change of rate: -1%

Value: $299

Variance of: $108

The Auditor General made an observation in the 2015–16 Public Accounts of Canada that certain discount rates used by the government to measure significant long-term liabilities are at the higher end of the acceptable range when compared with market trends.

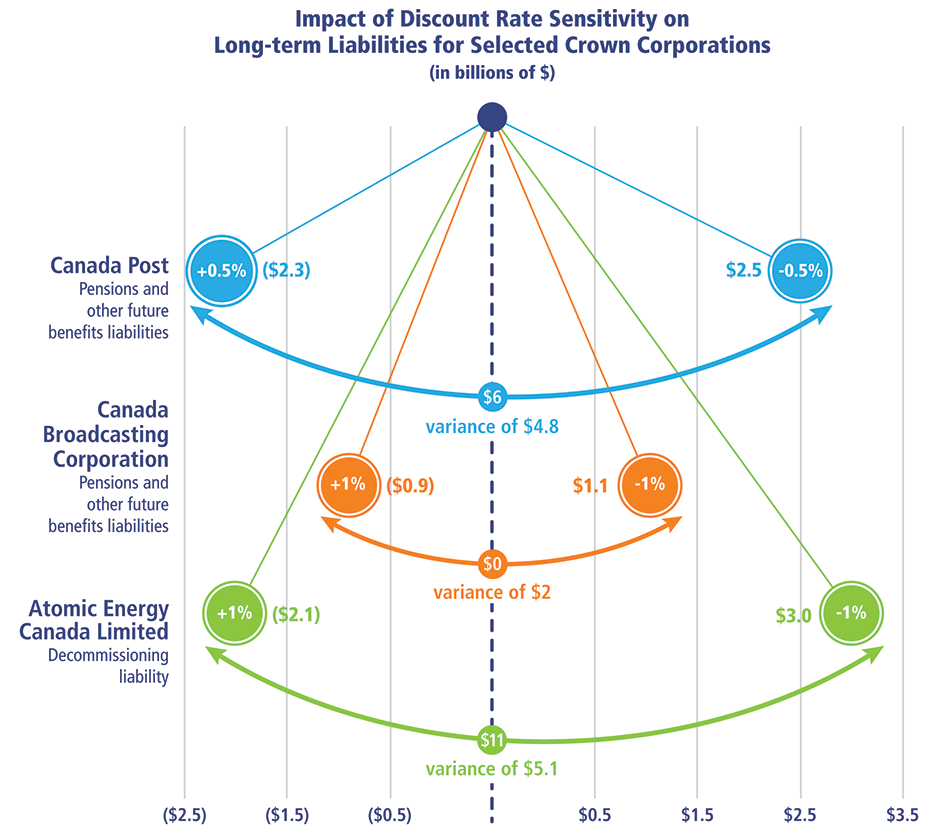

This chart further illustrates the significant impact that a change in the discount rate can have on the long-term liabilities of selected Crown corporations.

The corporations use different changes in the discount rate in their sensitivity analyses. Canadian Broadcasting CorporationCBC and Atomic Energy of Canada LimitedAECL use 100 basis points while Canada Post uses 50 basis points.

Source: Individual audited financial statements as at the most recent fiscal year end.

Text version

Impact of discount rate sensitivity on long-term liabilities for selected Crown corporations (in billions of dollars)

Canada Post—Pensions and other future benefits liabilities

Starting value: $6

Change of rate: +0.5%

Value: $2.3

Change of rate: -0.5%

Value: $2.5

Variance of: $4.8

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation—Pensions and other future benefits liabilities

Starting value: $0

Change of rate: +1%

Value: $0.9

Change of rate: -1%

Value: $1.1

Variance of: $2

Atomic Energy of Canada Limited—Decommissioning liability

Starting value: $11

Change of rate: +1%

Value: $2.1

Change of rate: -1%

Value: $3.0

Variance of: $5.1

Observations from the 2015–16 financial audits

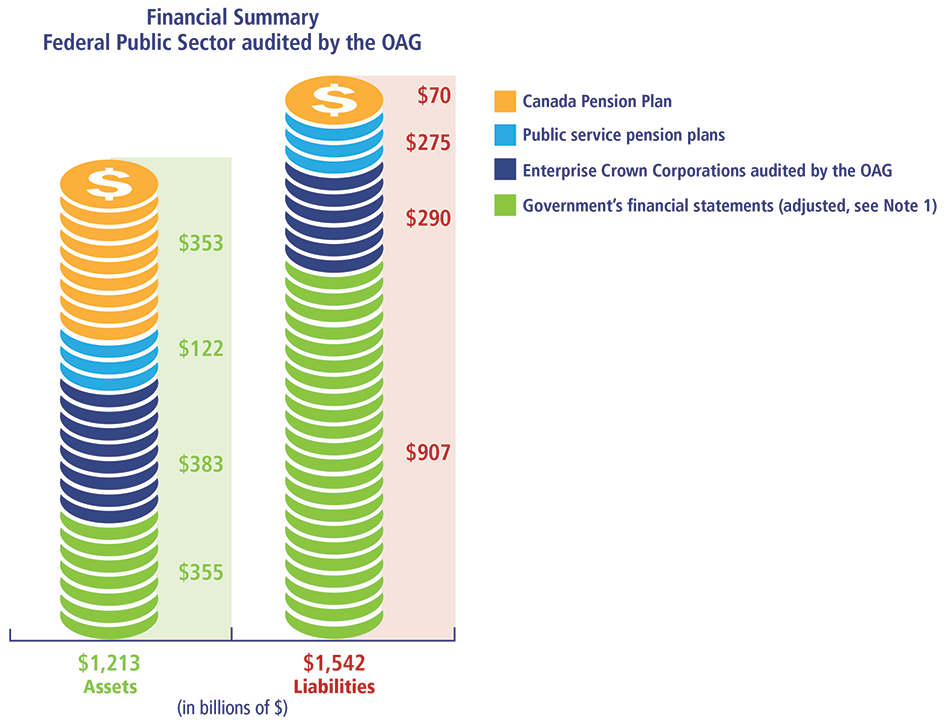

The Office was mandated to perform financial statement audits of 69 federal organizations (see Appendix) for the 2015–16 fiscal year, at a cost of $29 million. These audits include the financial statement audit of the Government of Canada as a whole, which is the biggest financial audit in Canada. It represents over 30 percent of the Office’s financial audit workload.

For the 2015–16 fiscal year, the Office’s federal financial audits covered, on a combined basis, assets of $1.2 trillion and liabilities of $1.5 trillion.

1 The Government of Canada’s consolidated balances have been adjusted to exclude investments, loans, and advances to government business enterprises audited by the Office, and the net pension liability for the funded public sector pension plans.

Text version

Financial Summary—Federal Public Sector audited by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada

| Category | Assets (in billions of dollars) |

Liabilities (in billions of dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| Canada Pension Plan | $353 | $70 |

| Public sector pension plans | $122 | $275 |

| Enterprise Crown Corporations audited by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada | $383 | $290 |

| Government’s financial statements (adjusted, see note 1) | $355 | $907 |

| Total | $1,213 | $1,542 |

1 The Government of Canada’s consolidated balances have been adjusted to exclude investments, loans, and advances to government business enterprises audited by the Office, and the net pension liability for the funded public sector pension plans.

Overall, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada was satisfied with the credibility of the 69 financial statements prepared by the Government of Canada and the federal organizations that the Office audits, with one exception.

We were pleased to report that the Office provided the Government of Canada with an link to Financial Audit Glossaryunmodified audit opinion on its consolidated financial statements for the eighteenth consecutive year. An unmodified audit opinion means that, in the auditor’s opinion, the financial statements gave a fair presentation of the underlying transactions and events in accordance with accounting requirements and complied with laws and regulations. The Auditor General addressed the following three matters in his observations in the 2015–16 Public Accounts of Canada:

- transformation of pay administration,

- the National Defence inventory, and

- liability for contaminated sites.

Of the remaining 68 financial statement audits conducted for the 2015–16 fiscal year, the Office issued 67 unmodified audit opinions. The exception relates to National Defence’s Reserve Force Pension Plan, for which the Office was unable to issue an audit opinion because of significant data quality problems.

The Office is satisfied that based on its examination of the transactions that came to its attention during the 2015–16 financial statement audits, there was no significant instance of non-compliance with laws, regulations, directives, or bylaws by any of the government departments or the individual organizations it audits.

The mandates of government organizations, their powers, and their governance structures can be set out in any number of binding instruments, which include laws, regulations, directives, and bylaws. Compliance with these instruments is important because they are intended to impose accountability, limit government spending, spell out minimum financial management practices and support the oversight of institutions' operations and performance.

The Office was satisfied with the timeliness of reporting by the government and the federal organizations the Office audited for the 2015–16 fiscal year.

Delays in financial reporting are rare, and if they occur, they are usually due to external or other circumstances over which the organization has little control. In addition, delays are typically limited to a few months.

Timeliness is important because decision makers need to receive financial information at the right time to consider that information when making decisions about an organization’s priorities. Similarly, elected officials need to receive relevant information at the right time to exercise oversight over government operations.

For the Government of Canada and its many federal departments and organizations, the deadlines for preparing and issuing audited annual financial statements are set in legislation. These annual deadlines typically range from 90 to 120 days following the end of an organization’s fiscal year. In the case of federal pension plans, the legislative deadlines extend to 12 months.

For organizations that do not have a legislated reporting deadline (such as agents of Parliament, the Canada Pension Plan, and the Employment Insurance Operating Account), the Office considers that financial statements issued within 150 days after the fiscal year-end are timely.

The Reserve Force Pension Plan was introduced in 2007 to cover reservists in the Canadian Armed Forces, and the Office was appointed as the Plan’s auditor in 2008.

In our audit, we could not determine whether the financial statements for the first two fiscal years of the Plan’s existence reliably presented the financial position of the Plan and the results of operations. This is largely because a backlog in unprocessed pension buybacks made it impossible for National Defence to report reliable estimates of the total accrued pension liability and contributions receivable for the Plan. Combined with errors and control weaknesses, this resulted in a denial of opinion on the financial statements. The audit of the Reserve Force Pension Plan financial statements was then suspended. The Office subsequently undertook a performance audit on the matter, which it reported in Spring 2011.

The Office resumed auditing the Plan’s financial statements for the year ended 31 March 2014. Again, we were unable to obtain all the necessary supporting documentation for data used to estimate the pension liability and contributions received from plan members. As a result, the Office issued a disclaimer of opinion.

For the fiscal year ended 31 March 2015, National Defence asked the Office not to conduct an audit. This was because the estimate for the pension obligation would be based on the same actuarial valuation as the previous year. The Office instead began to assess the auditability of the Plan’s data. Though this work was ongoing as of 30 September 2016, it was sufficiently advanced for us to determine that although the situation had improved, we would still be unable to obtain enough supporting documentation for the data used to determine the pension obligations and issue the audit opinion. Similarly, we have not audited the Plan’s financial statements for the year ended 31 March 2016.

National Defence’s slow progress in resolving this matter is unacceptable. In the nine years since the Reserve Force Pension Plan’s creation, the Office has been unable to provide parliamentarians and plan members with assurance that the Plan’s financial statements, which include a reported pension liability of $650 million, are free of significant error. This situation leaves parliamentarians and Plan members without assurance that the Plan’s financial statements present credible information about the Plan’s finances.

Conclusion

Elected officials are tasked with overseeing and managing the government’s finances on behalf the citizens who elect them. To carry out their duties with diligence, it is critical that they understand not only the information put before them, but also the story behind those numbers.

This is where I believe that my Office can add value. We have developed this report to help elected officials navigate the world of financial reporting as a whole, and to create an opportunity to bring to their attention trends, questions or issues coming out of our financial audit work across government.

We hope to see this report evolve into something that will help parliamentarians better understand the financial audits that our Office performs and navigate the masses of financial information that government organizations produce. To do so most effectively, we welcome their input, so that this report can evolve to meet their needs as they carry out their oversight role.