The climate crisis

A changing climate poses real risks for Canadians and the planet

“Humanity is conducting an unintended, uncontrolled, globally pervasive experiment whose ultimate consequences could be second only to a global nuclear war. … Far‑reaching impacts will be caused by global warming and sea‑level rise, which are becoming increasingly evident. … The best predictions available indicate potentially severe economic and social dislocation for present and future generations. … It is imperative to act now.”

This passage might sound like a recent United Nations speech, but in fact it comes from the proceedings of the World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere, which was held in Toronto in 1988.

Since then, the science has become far more definitive, the expected effects have materialized, and the need for action to address what is now a climate crisis has only increased. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that human activities have already caused global warming of 1.1 degrees Celsius above pre‑industrial levels. Global surface temperature will continue to increase until at least the mid‑century and exceed 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius during this century unless there are deep reductions to greenhouse gasDefinition 1 emissions. Increases in greenhouse gases are a primary cause of climate change. This is not merely a matter of global warming: The panel projects more extreme heat in most inhabited regions, heavy precipitation in several regions, and a higher probability of drought and precipitation deficits in other regions. Sea‑level rise, biodiversity loss, and species extinctions will also increase. Research also reveals the human health effects of climate change. For example, a recent study found that one third of heat‑related deaths worldwide can be attributed to climate change.

Once warming occurs, its effects may be long‑lasting or effectively irreversible. There is increasing evidence that the climatic system may be approaching a series of tipping points, which are critical thresholds beyond which a system reorganizes, often abruptly or irreversibly. This can include, for example, loss of ice from the Antarctic Ice Sheet, loss of forests, or weakening of ocean currents, which can change global weather patterns. This further underscores the need for concerted action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change’s deadly effects.

For Canada, a vast and diverse country, climate change affects regions differently. Several regions are already experiencing devastating heat waves, wildfires, and flooding because of climate change. Modelling from the Government of Canada shows that the North, much of which is underlain by permafrost, is warming at more than double the global rate. The ocean surrounding Canada has also warmed and has become more acidic and less oxygenated over the past century. These waters are expected to continue becoming less hospitable to marine life, while more of the Arctic and Atlantic oceans will become ice‑free. Flooding on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and the Beaufort coast in the North further increases the risk of damage to infrastructure and ecosystems.

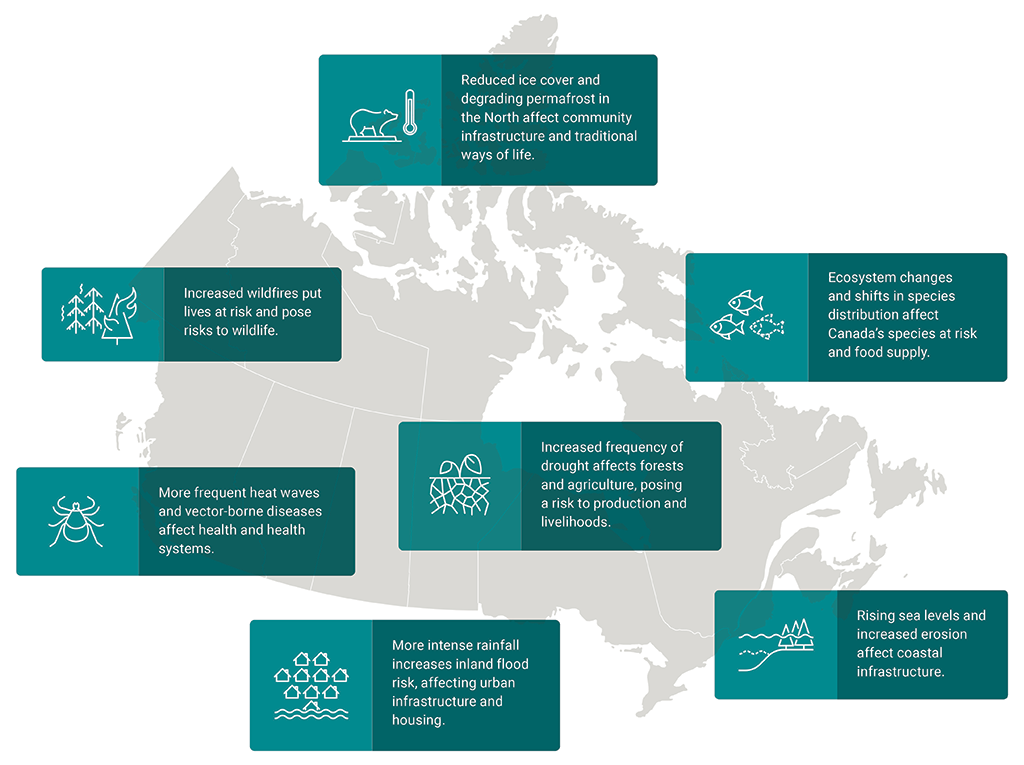

These effects translate into risks to physical infrastructure, coastal and northern communities, natural resources, biodiversity, ecosystems, ecological cycles, and human health (Exhibit 5.1). For instance, increased numbers of wildfires, heat waves, and vector‑borne diseases put lives at risk. The increased frequency of droughts in certain regions affects forests and agriculture, posing a risk to production, livelihoods, and the food supply. Ecosystem changes and shifts in species distribution affect Canada’s species at risk.

Exhibit 5.1—The physical effects of climate change pose real risks for Canadians

Source: Adapted from Canada’s Sixth National Report on Climate Change: Actions to Meet Commitments Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Government of Canada, 2014; Canada’s Top Climate Change Risks: Expert Panel on Climate Change Risks and Adaptation, Council of Canadian Academies, 2019

Exhibit 5.1—text version

This image consists of a map of Canada with the following descriptions of climate change effects:

- Reduced ice cover and degrading permafrost in the North affect community infrastructure and traditional ways of life.

- Increased wildfires put lives at risk and pose risks to wildlife.

- Ecosystem changes and shifts in species distribution affect Canada’s species at risk and food supply.

- More frequent heat waves and vector-borne diseases affect health and health systems.

- Increased frequency of drought affects forests and agriculture, posing a risk to production and livelihoods.

- More intense rainfall increases inland flood risk, affecting urban infrastructure and housing.

- Rising sea levels and increased erosion affect coastal infrastructure.

Economists largely agree that costs related to climate change will increase as emissions grow. The Canadian Institute for Climate Choices estimates that the average cost per disaster in Canada has increased more than tenfold since the 1970s.

The experience of climate change is highly unequal. Certain populations bear a disproportionate burden and are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change because they are less able to anticipate, cope with, and recover from adverse effects. These groups can include, but are not limited to, racial minorities, women and girls, low‑income populations, and the elderly. Additionally, youth and future generations face intergenerational equity issues as they will be burdened by the consequences of an increasingly dangerous climate.

Geographic exposure or reliance on certain economic sectors can also increase the vulnerability of certain communities to climate change. In Canada, climate change has disrupted access to Indigenous and northern communities, threatened cultural sites, and adversely affected traditional activities, such as hunting, fishing, and foraging. In the Arctic, the well‑being of local communities is being affected as climate change compromises the availability of traditional foods and water supplies. Many coastal communities face the risk of tidal flooding and storm surges, while some face irreversible effects of sea‑level rise. Climate change will also adversely affect certain economic sectors, such as forestry, agriculture, and fisheries.

About the report

The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development and the Auditor General of Canada have been reporting to Parliament on Canada’s climate change performance since 1998 (see Appendix). Major international commitments to fight climate change, of which Canada has been a part, date back to 1992. In undertaking this look at 3 decades of Canadian action and inaction on climate change, we reviewed our previous audit recommendations and interviewed senior climate experts, former government officials, and former commissioners.

Drawing from this collective experience, this report identifies trends in Canada’s efforts to fight climate change, along with 8 lessons learned from Canadian accomplishments and mistakes:

- Lesson 1: Stronger leadership and coordination are needed to drive progress toward climate commitments

- Lesson 2: Canada’s economy is still dependent on emission‑intensive sectors

- Lesson 3: Adaptation must be prioritized to protect against the worst effects of climate change

- Lesson 4: Canada risks falling behind other countries on investing in a climate‑resilient future

- Lesson 5: Increasing public awareness of the climate challenge is a key lever for progress

- Lesson 6: Climate targets have not been backed by strong plans or actions

- Lesson 7: Enhanced collaboration among all actors is needed to find climate solutions

- Lesson 8: Climate change is an intergenerational crisis with a rapidly closing window for action

This is not an audit report. Instead, this report provides a historical perspective on Canada’s action to address climate change mitigation and adaptation in order to inform parliamentarians. Parliamentarians are instrumental in ensuring that Canada transitions to a low‑emission economy and ultimately must hold the government to account in meeting its climate change objectives. This report also aims to build Canadians’ awareness of the climate crisis, to share the Commissioner’s views, and to position future work on Canada’s climate change efforts.

To help frame future discussions and actions on climate change, this report provides some critical questions to consider as governments across Canada move forward on their climate change commitments. The aim is to help Canada learn from past failures so that it can translate its good intentions into positive outcomes. Continued failure is not an option if Canada and the rest of the world are to protect the earth and humanity from catastrophic climate change.

Given the momentum created by the global climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, this year, the moment to act on climate is now.

Appendix—Reports of the Commissioner and Auditor General on Canada’s climate performance

The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development and the Auditor General of Canada have been reporting to Parliament on Canada’s climate change performance since 1998. However, mentions of climate change in audit reports started as early as 1985. Themes range from mitigation and adaptation to governance and delve into topics such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating the effects of severe weather, phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, and developing sustainable infrastructure and clean energy technologies. We have audited Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada most frequently on these topics, but we have also included Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada, Transport Canada, Health Canada, and the Department of Finance Canada, among others (Exhibit 5.14).

Exhibit 5.14—Summary of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s climate‑related audits and key findings

2021—Investing in Canada Plan (Auditor General’s report)

- The plan includes funding for mitigating climate change’s effects on existing infrastructure.

- The federal government was unable to provide meaningful public reporting on the plan’s overall progress toward its expected results.

2019—Review of the 2018 Progress Report on the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development’s report)

- The government’s projected 2030 greenhouse gas emission values and documentation failed to demonstrate that its existing and planned actions would enable Canada to meet the country’s 2030 target for emission reductions.

2019—Non‑Tax Subsidies for Fossil Fuels and Tax Subsidies for Fossil Fuels (Commissioner’s reports)

- The government did not have a complete inventory of potential fossil fuel subsidies.

- The government did not conduct a rigorous assessment of its potential non‑tax subsidies inventory to determine whether they were actual subsidies.

- Canada’s assessments to identify inefficient tax subsidies for fossil fuels were incomplete and did not clearly define how a tax subsidy for fossil fuels would be inefficient.

2018—Perspectives on Climate Change Action in Canada—A Collaborative Report from Auditors General (Commissioner’s report)

- Canada was not on track to meet its 2020 target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Meeting Canada’s 2030 target would require substantial effort and actions beyond those currently planned or in place.

- Most Canadian governments had not assessed and did not fully understand what risks they face and what actions they should take to adapt to a changing climate.

2018—Climate Change in Nunavut (Auditor General’s report)

- The Government of Nunavut was not adequately prepared to respond to climate change. It lacked implementation plans for its adaptation and emission strategies.

- The Government of Nunavut did not fully assess the risks of climate change to Nunavut.

2017—Progress on Reducing Greenhouse Gases (Commissioner’s report)

- Canada was not on track to meet its 2020 emission target and had shifted its focus to a 2030 emission target.

2017—Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change (Commissioner’s report)

- No priorities were set and no adaptation action plans were instituted to advance the Federal Adaptation Policy Framework across the federal government.

2017—Climate Change in Yukon (Auditor General’s report)

- The Government of Yukon created a strategy, an action plan, and 2 progress reports to respond to climate change. However, the commitments were weak and not prioritized.

- Deficiencies in reporting made it difficult to assess progress.

2017—Climate Change in the Northwest Territories (Auditor General’s report)

- The territory’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources did not identify climate change risks and did not establish a territorial adaptation strategy.

- The Government of Northwest Territories departments and communities pursued their own adaptation efforts, resulting in a piecemeal and uncoordinated approach to adaptation.

2017—Fossil Fuel Subsidies (Auditor General’s report)

- The government did not define what the 2009 G20 commitment to phase out and rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies meant in the context of Canada’s national circumstances.

2017—Funding Clean Energy Technologies (Commissioner’s report)

- The government had rigorous and objective processes in place to assess, approve, and monitor projects.

2016—Mitigating the Impacts of Severe Weather (Commissioner’s report)

- The government had not done enough to help mitigate the anticipated effects of severe weather events.

2016—Federal Support for Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure (Commissioner’s report)

- The government could not adequately demonstrate that the Gas Tax Fund had resulted in reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

2014—Mitigating Climate Change (Commissioner’s report)

- Canada would not meet its 2020 emission reduction target.

- The federal government had no plan for working toward the greater reductions required beyond 2020.

- There was no coordination with provinces and territories to achieve the national target.

2012—Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments (Commissioner’s report)

- Canada was not on track to meet its 2020 emission target under the Copenhagen Accord.

2011—Climate Change Plans under the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act (Commissioner’s report)

- Canada was not on track to meet its Kyoto Protocol greenhouse gas emission target.

- The governance mechanisms for climate change were inadequate.

2010—Adapting to Climate Impacts (Commissioner’s report)

- No concrete actions were taken to adapt to the effects of a changing climate.

2009—Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act (Commissioner’s report)

- The climate change plans overstated the reductions that could be reasonably expected.

- Climate plans lacked transparency.

- Reporting was deficient.

2006—Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change (Commissioner’s report)

- The government had not put in place key measures to support climate adaptation and had no strategy for federal adaptation efforts to indicate expected results and timelines and for which departments would assume responsibilities.

- Federal progress in working with provinces and territories was limited.

2006—Managing the Federal Approach to Climate Change (Commissioner’s report)

- Canada was not on track to meet its Kyoto Protocol greenhouse gas emission target.

- Governance mechanisms for climate change were inadequate.

- Reporting was deficient.

2001—Climate Change and Energy Efficiency: A Progress Report (Commissioner’s report)

- Despite some progress, the federal government had a great deal of work left to do to engage partners to take action on climate change.

- Action Plan 2000 lacked specific performance expectations.

1998—Responding to Climate Change: Time to Rethink Canada’s Implementation Strategy (Commissioner’s report)

- Governance mechanisms for climate change were inadequate.

1997—Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the House of Commons (Commissioner’s report)

- This was the first of the Commissioner’s reports. Climate change is mentioned as a key issue of concern to Canadians and as the subject of one of the first reports to be issued by the Commissioner.

Future work from the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

The Commissioner’s mandate has been expanded by the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act. This act requires the Commissioner to examine and report on the government’s implementation of measures aimed at mitigating climate change. This reporting may include recommendations on improving the effectiveness of the implementation of these measures. The Commissioner welcomes the formalization of the requirement to report to Parliament on Canada’s climate change performance given that the Office of the Auditor General of Canada has been issuing reports on climate change regularly since 1998.

Given the magnitude of the climate crisis, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada will devote significant resources to audits and studies related to climate change. For example, the release of this report coincides with a performance audit of Canada’s Emissions Reductions Fund. And in 2022, we look forward to sharing with Parliament and Canadians our upcoming audit work on carbon pricing, just transition, hydrogen, greening government operations, and climate‑resilient infrastructure, as well as a study on climate‑related financial disclosure.