Canada’s commitments and actions on climate change

Canada’s record on climate change should be judged not only on the targets and commitments that Canada has made over the years, but also on its actions. Despite commitments from government after government to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the past 3 decades, Canada has failed to translate these commitments into real reductions in net emissions. Instead, Canada’s emissions have continued to rise. Meanwhile, the global climate crisis has gotten worse. However, the recent coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 2 pandemic has shown that Canada does have the capacity to respond to crises. Will Canada finally turn the corner and do its part to reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

Canada has participated in more than 30 years of international collective action on climate change

Globally, scientific research has focused on climate change since the late 1980s. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was established in 1988 to assess changes in climate and provide governments with scientific information to guide climate policies. Through this panel, scientists and other experts from around the world, including Canada, synthesize the most recent developments in climate science, adaptation, vulnerability, and mitigation. Over decades, the panel’s key findings have more definitively outlined the types and severity of change in our climate—and attributed much of it to human activity.

In June 1992, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, hosted the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. This conference launched the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Signatories, including Canada, agreed to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous interference with the climate. Canada has been party to all major international climate change agreements since then (Exhibit 5.2).

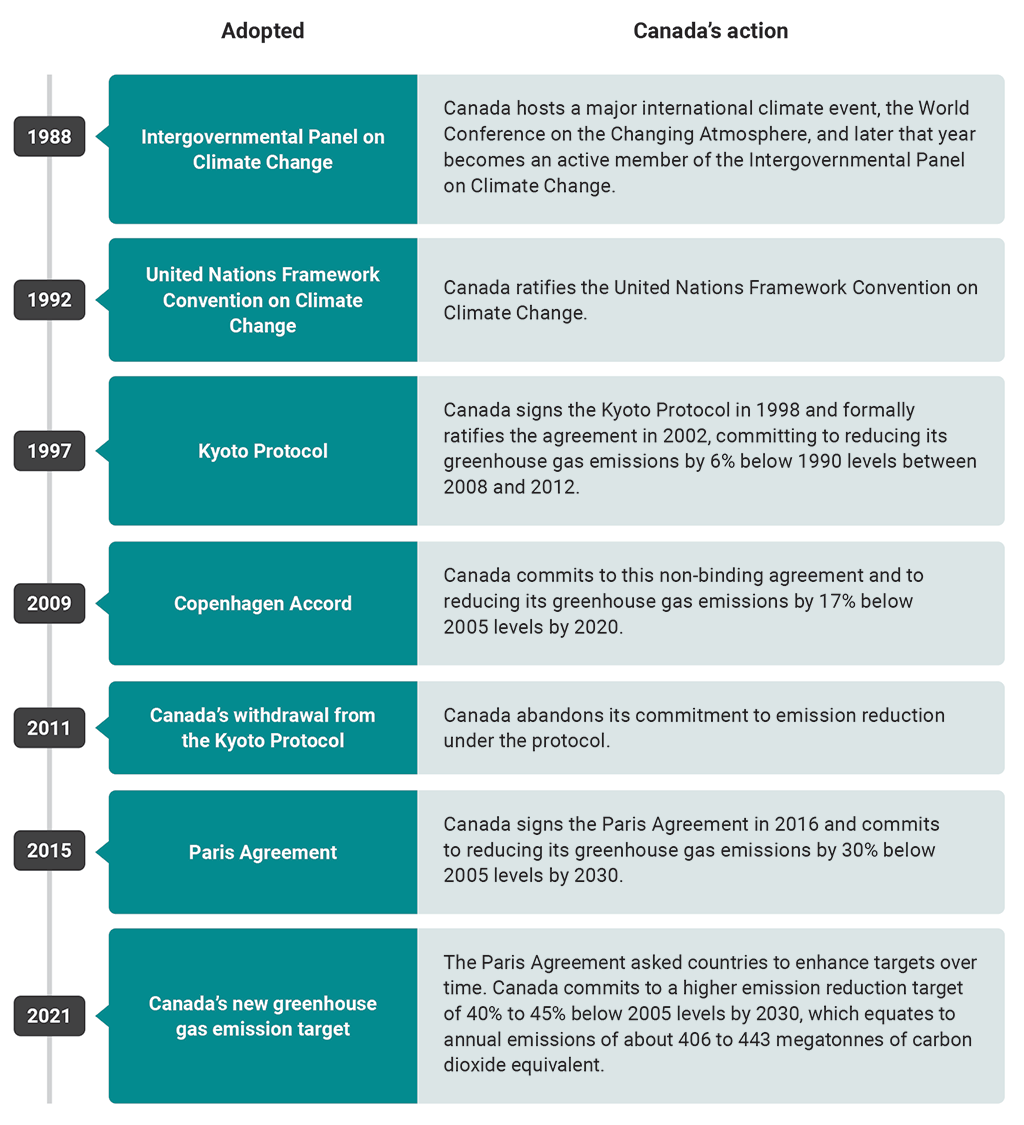

Exhibit 5.2—Canada’s climate action and participation in major international climate agreements

Exhibit 5.2—text version

This timeline shows Canada’s action on climate change and participation in major international climate agreements.

1988—Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- Canada hosts a major international climate event, the World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere, and later that year becomes an active member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

1992—United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- Canada ratifies the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

1997—Kyoto Protocol

- Canada signs the Kyoto Protocol in 1998 and formally ratifies the agreement in 2002, committing to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 6% below 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012.

2009—Copenhagen Accord

- Canada commits to this non-binding agreement and to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 17% below its 2005 level by 2020.

2011—Canada’s withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol

- Canada abandons its commitment to emission reduction under the protocol.

2015—Paris Agreement

- Canada signs the Paris Agreement in 2016 and commits to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.

2021—Canada’s new greenhouse gas emission target

- The Paris Agreement asked countries to enhance targets over time. Canada commits to a higher emission reduction target of 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030, which equates to annual emissions of about 406 to 443 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

In 2015, 196 countries adopted the landmark Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change. The goal of the Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, relative to pre‑industrial levels. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, to achieve this goal and a net‑zero‑emission world by 2050, countries must significantly reduce their greenhouse gas emissions without delay. However, current global commitments fall far short of this, leading to projections of warming by 3 degrees Celsius by 2100.

Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions have increased in the past 30 years

Since 1990, the Government of Canada has made many domestic and international commitments to address climate change, including commitments to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and reach net‑zero emissions by 2050. The 2 most recent domestic plans were the 2016 Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change and A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy in 2020 (Exhibit 5.3). In 2021, the government announced a new target to reduce emissions but has not yet issued an updated climate plan.

Exhibit 5.3—Canada has 2 climate change plans in effect

The 2016 Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change was Canada’s first‑ever national climate plan, developed in collaboration with provinces and territories and with input from Indigenous peoples. It included over 50 measures to reduce carbon emissions. Some of the key commitments in the framework include

- carbon pricing in all jurisdictions by 2018

- a nationwide strategy for electric vehicles by 2018

- a federal clean fuel standard that will require liquid fuel suppliers to reduce carbon intensity by 2030

- an accelerated nationwide coal phase‑out by 2030

- methane regulations for the oil and gas sector

- investment in clean technology

Canada’s A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy plan, launched in 2020, builds on the framework and the 2018 Generation Energy Council report, which outlined 4 pathways that could lead Canada to an affordable, sustainable energy future. A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy contains 64 new or strengthened federal policies, programs, and investments to cut carbon emissions. The plan’s 5 key pillars are

- making the places Canadians live and gather more affordable by cutting energy waste

- making clean, affordable transportation and power available in every Canadian community

- continuing to ensure pollution isn’t free and households get more money back

- building Canada’s clean industrial advantage

- embracing the power of nature to support healthier families and more resilient communities

The plan also contains new measures to support Indigenous climate leadership, to cut emissions from waste and from federal operations, and to introduce nature‑based climate solutions, such as planting trees and restoring grasslands.

Repeated commitments, strategies, and action plans to reduce emissions in Canada have not yielded results (Exhibit 5.4). According to Canada’s 2021 National Inventory Report, Canada’s emissions were 730 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalentDefinition 3 in 2019, while its target for 2020 was 607 megatonnes. Canada’s new target for 2030 equates to approximately 406 to 443 megatonnes. Despite progress in some areas, such as public electricity and heat generation, Canadian emissions have actually increased by more than 20% since 1990.

Exhibit 5.4—Canada’s overall emissions grew from 1990 to 2019, despite numerous plans for reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Source: Based on emission data from Canada’s 2021 National Inventory Report

Exhibit 5.4—text version

This line graph shows Canada’s overall greenhouse gas emissions in megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent from 1990 to 2019. The graph also shows when the Government of Canada released its numerous climate action plans during this period.

In 1990, Canada emitted 602 megatonnes. In that year, the government released Canada’s Green Plan.

After dropping slightly in 1991, emissions steadily rose to 656 megatonnes in 1995. In that year, the government released the National Action Program on Climate Change.

Emissions continued to rise to 734 megatonnes in 2000. In that year, the government released the Government of Canada Action Plan 2000 on Climate Change.

After dropping slightly in 2001, emissions rose to 727 megatonnes in 2002. In that year, the government released Climate Change—Achieving Our Commitments Together.

Emissions rose slightly to 739 megatonnes in 2005. In that year, the government released Project Green.

After falling slightly in 2006, emissions rose again to 752 megatonnes in 2007. In that year, the government released Turning the Corner.

After falling in 2009, emissions rose to 703 megatonnes in 2010. In that year, the government released A Climate Change Plan for the Purposes of the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act.

Emissions rose slightly over the next 5 years but fell to 707 megatonnes in 2016. In that year, the government released the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change.

Emissions rose to 730 megatonnes in 2019. In the following year, the government released A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy.

Canada has made some progress in decoupling emissions from population growth and its gross domestic product: Canada’s population and economy have grown faster than emissions have. However, Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions have increased since the Paris Agreement was signed, making it the worst performing of all Group of 7G7 nations since the 2015 Conference of the Parties in Paris, France.

Climate change and the Sustainable Development Goals

In September 2015, Canada joined 192 countries in committing to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This agenda is a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and improve prosperity, peace, and partnership, with a focus on helping the most vulnerable first and leaving no one behind. The agenda sets out 17 Sustainable Development Goals, which cover a broad range of social, economic, and environmental issues, such as poverty, health, gender equality, sustainable economic growth, water, and climate change.

In 2017, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada committed to examining in its performance audits and special examinations how federal organizations are contributing to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. The matters examined in this report relate to Goal 13, which commits governments to “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.” Many of the other Sustainable Development Goals contain elements relevant to climate change, such as the goals of

- affordable and clean energy (Goal 7)

- decent work and economic growth (Goal 8)

- industry, innovation and infrastructure (Goal 9)

- reduced inequalities (Goal 10)

- sustainable cities and communities (Goal 11)

- life below water (Goal 14)

- life on land (Goal 15)

- peace, justice and strong institutions (Goal 16)

We have undertaken several audits related to these goals and their targets and will continue to do so as a means of contributing to the monitoring of national and international progress toward the agenda and the goals.

What Canada can learn from the COVID‑19 crisis

The COVID‑19 pandemic has shown that strong, concerted government action can avert the worst of a crisis. But the longer‑term crisis of climate change looms larger than ever.

Governments in Canada and around the world responded to COVID‑19 in various ways: lockdowns and curfews, mask mandates, vaccine rollouts, support for workers and small businesses affected by economic shutdowns, and the procurement of personal protective equipment and ventilators. Jurisdictions whose governments took strong initial steps and followed scientific advice generally fared better than those that did not.

Like pandemics, climate change is a global crisis, which experts have been raising alarms about for decades. Pandemics and climate change both carry risks to human health and the economy, and both require whole‑of‑society responses to prevent further catastrophe.

This suggests that Canadians can draw crisis management lessons from the COVID‑19 pandemic. As well, pandemic economic recovery efforts will provide opportunities for the emergence of a stronger, more climate‑resilient society—if governments at all levels, citizens, the private sector, and civil society work together.

Report team

Principal: Kimberley Leach

Director: Elsa Da Costa

Vanessa Alboiu

Kate Kooka

Julia Sweatman