2023 Reports 5 to 9 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 9—Processing Applications for Permanent Residence—Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 9.1—Permanent resident admission targets increased under the Immigration Levels Plan

- 9.2—We examined the processing of applications in 8 permanent resident programs in 2022

- 9.3—Overview of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s application process for permanent residence

- 9.4—Processing times decreased for economic and family class applicants but not for refugee and humanitarian class applicants

- 9.5—In 2022, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s performance fell short of its service standards

- 9.6—At the start of 2022, inventory volumes exceeded the number of applications that could be processed for the majority of programs

- 9.7—Large and aging application backlogs persisted across permanent resident programs—more than half of the applications remained backlogged at the end of 2022

- 9.8—Four of the top 5 factors contributing to processing delays were under the department’s control

- 9.9—Applications automatically deemed eligible were finalized faster than those that were not

Introduction

Background

9.1 Canada welcomes permanent residents with the aims of driving economic growth, reuniting families, and upholding humanitarian values. There are 3 broad categories of permanent resident programs:

- Economic Class—for people who have the skills and experience to meet Canada’s current economic and labour needs

- Family Class—for the sponsorship of spouses, common‑law and conjugal partners, dependent and adoptive children, parents, grandparents, and other eligible relatives

- Refugee and Humanitarian Class—for people seeking protection from violence or fleeing precarious or unsafe environments and for people in exceptional circumstances applying on humanitarian and compassionate grounds

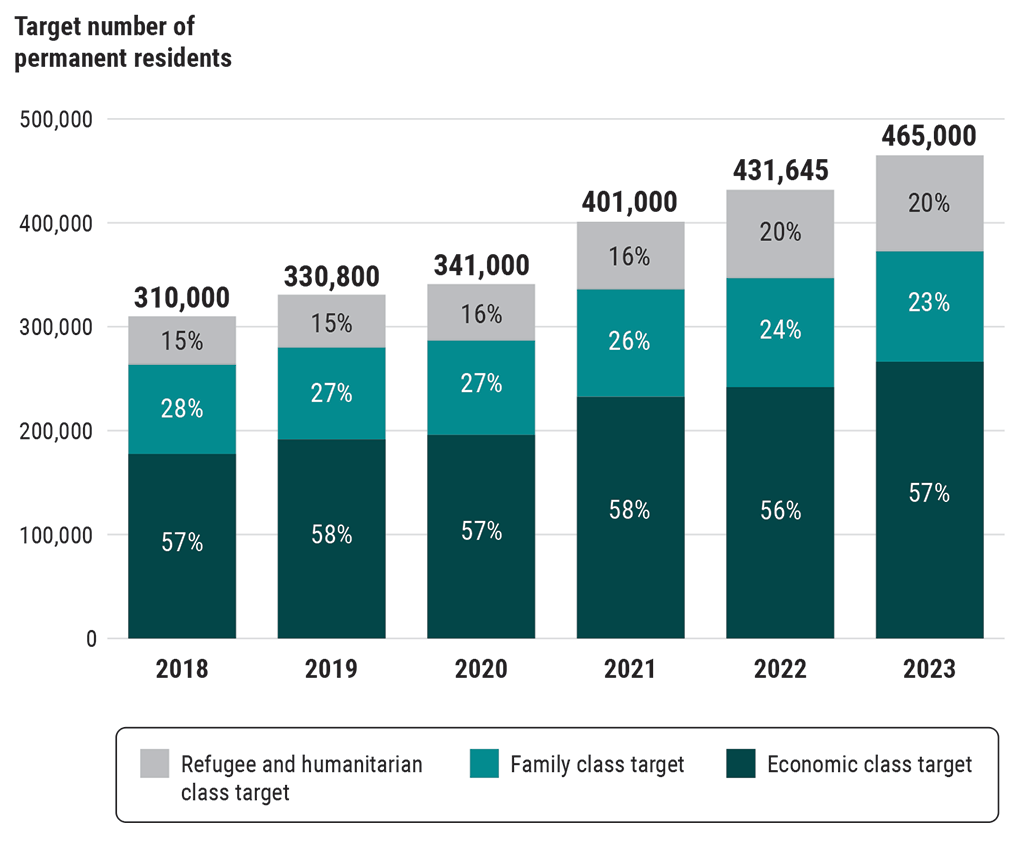

9.2 Each year, Canada sets numerical targets for new permanent resident admissions under the Immigration Levels Plan. Since 2018, these numbers have been climbing (Exhibit 9.1), and every year except 2020, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has met this target. In 2022, the department met the admission target of 431,645 new permanent residents, surpassing its previous record in 2021. In 2025, it expects to welcome 500,000.

Exhibit 9.1—Permanent resident admission targets increased under the Immigration Levels Plan

Source: Based on information from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Exhibit 9.1—text version

This chart shows the admission targets from 2018 to 2023 for the 3 categories of permanent resident programs: refugee and humanitarian class, family class, and economic class. The target number for permanent resident admissions increased every year during this 6‑year period.

In 2018, the admissions target was 310,000. Of this, 57% was for economic class programs, 28% was for family class programs, and 15% was for refugee and humanitarian class programs.

In 2019, the admissions target was 330,800. Of this, 58% was for economic class programs, 27% was for family class programs, and 15% was for refugee and humanitarian class programs.

In 2020, the admissions target was 341,000. Of this, 57% was for economic class programs, 27% was for family class programs, and 16% was for refugee and humanitarian class programs.

In 2021, the admissions target was 401,000. Of this, 58% was for economic class programs, 26% was for family class programs, and 16% was for refugee and humanitarian class programs.

In 2022, the admissions target was 431,645. Of this, 56% was for economic class programs, 24% was for family class programs, and 20% was for refugee and humanitarian class programs.

In 2023, the admissions target was 465,000. Of this, 57% was for economic class programs, 23% was for family class programs, and 20% was for refugee and humanitarian class programs.

9.3 The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act sets out objectives for consistent standards, prompt processing, and fair and efficient procedures for Canada’s immigration programs. However, the department has publicly reported that prospective immigrants can experience long processing times.

9.4 The coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1 pandemic significantly affected Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s processing operations. In 2020, the department temporarily closed its processing centres in Canada and abroad. Applicants faced global travel restrictions and limited access to visa application centres, immigration medical exams, biometrics collection, and the documents required to support their applications. At the end of 2021, the department reported processing delays in all of its permanent resident programs and an accumulation of more than 800,000 applications across these programs.

9.5 In the 2021–22 fiscal year, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada spent approximately $254 million to deliver its permanent resident programs. To support its growing admission targets, address ongoing application backlogs, and speed up processing, the government allocated separate funding in each of the following years:

- $62 million over 5 years starting in the 2020–21 fiscal year and $15 million ongoing

- $183 million over 5 years starting in the 2021–22 fiscal year and $36 million ongoing

- $430 million over 5 years starting in the 2022–23 fiscal year and $101 million ongoing

In addition, in the 2022–23 fiscal year, the government allocated another $28 million to reduce application backlogs and processing times.

9.6 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. The department is responsible for overseeing the efficiency and integrity of Canada’s immigration system. It receives applications for permanent residence, verifies documents, makes eligibility and admissibility decisions, and communicates with applicants about their applications. The department also develops and implements policies and procedures related to immigration.

Focus of the audit

9.7 This audit focused on whether Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada processed applications for permanent residence efficiently and promptly to support Canada’s economic, family reunification, and humanitarian goals. We looked at how efficiently the department processed applications in 8 permanent resident programs. This included examining how the department managed its inventory of applications and what strategies it used to address processing delays, including those resulting from the COVID‑19 pandemic.

9.8 We also examined the department’s processing capacity and workload distribution across its offices and programs and its ongoing transition to online processing.

To reduce inequalities, policies should be universal in principle, paying attention to the needs of disadvantaged and marginalized populations.

Source: United NationsFootnote 1

9.9 Efficiently and promptly processing permanent resident applications supports the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 10—Reduced Inequalities—specifically target 10.3, which relates to equal opportunities and outcomes, and target 10.7, which relates to the orderly, safe, regular, and responsible migration and mobility of people.

9.10 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Processing times improved but not for all applicants

9.11 This finding matters because Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has committed to reducing long wait times and backlogs for applicants to permanent resident programs. Prompt processing supports the government’s priorities of economic growth, family reunification, and refugee resettlement—a humanitarian value.

9.12 In addition, people who apply to Canada’s permanent resident programs should benefit from the government’s efforts to improve processing speeds regardless of their country of citizenship or the office where their application is sent for processing.

9.13 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada administers about 50 permanent resident programs across the economic, family, and refugee and humanitarian classes. We examined 8 programs that account for the majority of the permanent resident applications that Canada finalizes each year in each class (Exhibit 9.2).

Exhibit 9.2—We examined the processing of applications in 8 permanent resident programs in 2022

Total economic class applications finalized—331,217

| Programs we examined | Purpose | Number finalized in 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Federal Skilled Worker Program (Express Entry) | Attract skilled foreign workers who can fill labour gaps and contribute to Canada’s economy. Applications are received through the online Express Entry system. | 56,232 |

| Quebec-Selected Skilled Worker Program | Attract skilled foreign workers who want to live and work in Quebec. | 48,652 |

| Provincial Nominee Program (Non‑Express Entry) | Enable the provinces and territories to nominate for permanent residence foreign nationals who meet specific local labour market needs. | 60,383 |

| Provincial Nominee Program (Express Entry) | Enable the provinces and territories to use the Express Entry system to nominate for permanent residence a certain number of skilled workers to meet local immigration and labour market needs. | 63,805 |

Total family class applications finalized—125,700

| Programs we examined | Purpose | Number finalized in 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Overseas Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner Program | Support family reunification by enabling Canadian citizens and permanent residents to sponsor a spouse, common‑law partner, or conjugal partner who lives outside Canada. | 44,239 |

| Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada Program | Enable Canadian citizens and permanent residents to sponsor a spouse or common‑law partner currently living in Canada. | 37,618 |

Total refugee and humanitarian class applications finalized—110,245

| Programs we examined | Purpose | Number finalized in 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Government-Assisted Refugees Program | Provide protection and resettlement for refugees who are outside their home countries and cannot return because of risk of persecution or other critical threats. | 16,354 |

| Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program | Allow Canadian citizens, permanent residents, and registered refugee assistance organizations to sponsor and support refugees. Sponsors provide financial, emotional, and settlement support. | 31,494 |

Note: The number of applications that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada finalizes in any given year is higher than the annual admission targets to account for refused and withdrawn applications and approved applicants who do not arrive in Canada.

Source: Based on information and data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

9.14 The Immigration Levels Plan sets out admission targets across permanent resident programs, which thereby helps to determine the total number of applications that can be finalized each year. The size of the department’s application inventoryDefinition 2 depends on admission targets and on the number of new applications submitted. Select economic class programs limit the number of applications that can be submitted, but most family class and refugee and humanitarian class programs do not. This can cause the number of applications in the inventory to far exceed the annual admission targets, which affects processing times and backlogDefinition 3 sizes, particularly for refugees.

9.15 As a general operating principle, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada aims to process applications in each permanent resident program on a first‑in‑first‑out basis, meaning that cases should be processed in the order that applications are submitted. This principle may not be applied in certain circumstances, such as in the case of special measures programs that prioritize certain applications; for example, the Special Immigration Measures Program for Afghan nationals.

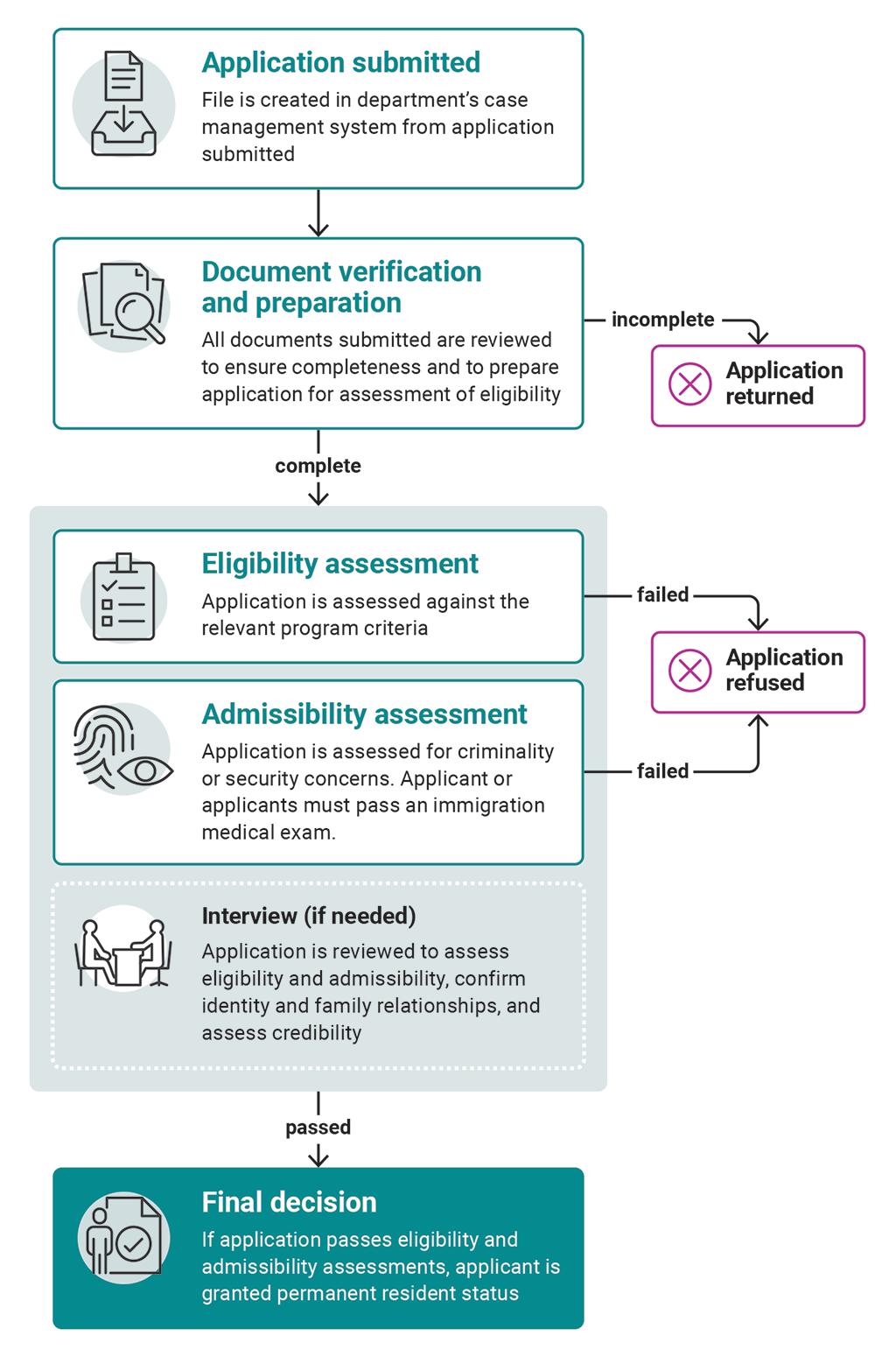

9.16 The department has also established service standardsDefinition 4 for several programs, which are meant to give applicants a realistic estimate of when to expect a decision after they submit an application. The department aims to meet its service standards for 80% of submitted applications and considers an application to be backlogged if its processing time does not meet the standard. For programs without service standards, the department uses an expected processing time of 12 months for analysis and reporting.

9.17 Exhibit 9.3 provides a simplified view of the application process for permanent resident programs. Processing time starts as soon as a completed application is received and ends once the final decision is made.

Exhibit 9.3—Overview of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s application process for permanent residence

Source: Based on information from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Exhibit 9.3—text version

This flow chart shows an overview of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s application process for permanent residence.

First, a file is created in the department’s case management system from the application submitted.

All documents submitted are then reviewed to ensure completeness and to prepare the application for assessment of eligibility. At this stage, if the documents are incomplete, the application is returned. If they are complete, the application moves on to the eligibility assessment.

During the eligibility assessment, the application is assessed against the relevant program criteria.

If the application passes the eligibility assessment, it is then assessed for admissibility. The application is assessed for criminality or security concerns, and the applicant or applicants must pass an immigration medical exam.

If an application fails either the eligibility assessment or the admissibility assessment, the application is refused. If it passes both steps, it moves on to the interview, if needed.

If an interview is needed, the application is reviewed to assess eligibility and admissibility, confirm identity and family relationships, and assess credibility.

Final decision—If the application passes eligibility and admissibility assessments, the applicant is granted permanent resident status.

Service standards not met across programs

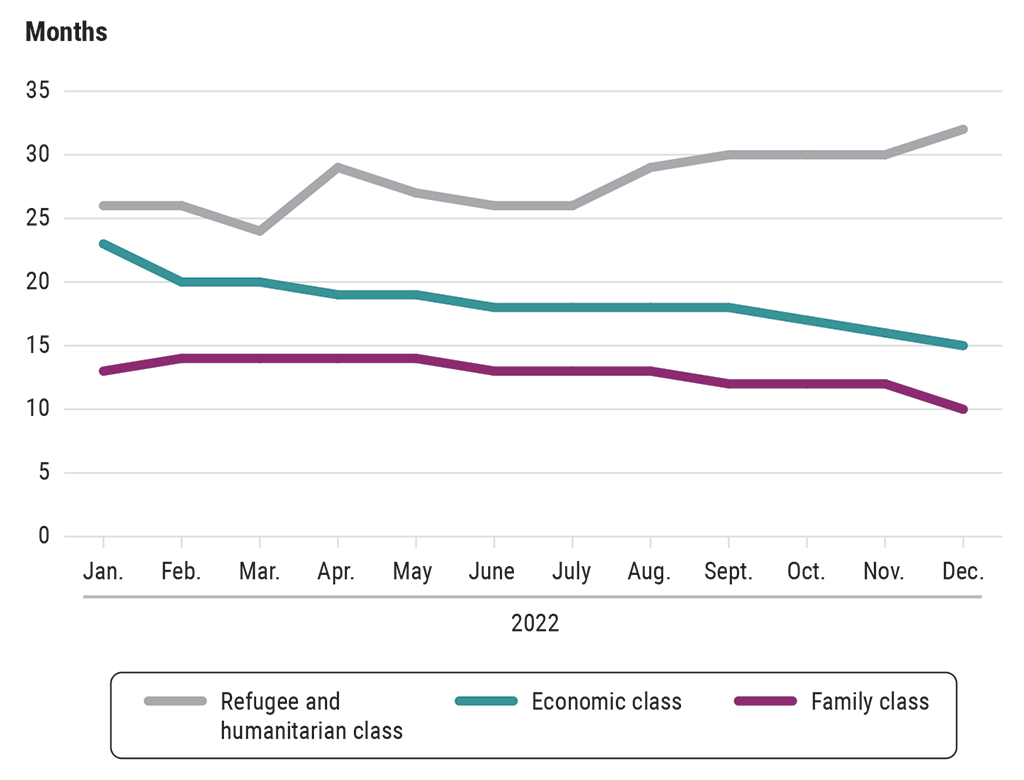

9.18 We found that in 2022, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada improved its processing times for most of the permanent resident programs we examined. Economic class applicants experienced the greatest improvement among all 3 immigration classes. Family class applicants also experienced improved processing times, with newer applications making up the majority of the applications processed. However, processing times remained long in refugee and humanitarian programs, with applicants waiting almost 3 years for a decision at the end of 2022 (Exhibit 9.4).

Exhibit 9.4—Processing times decreased for economic and family class applicants but not for refugee and humanitarian class applicants

Source: Based on information from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Exhibit 9.4—text version

This chart shows the processing times for refugee and humanitarian class, economic class, and family class applicants. Processing times are shown in months from January to December 2022.

Refugee and humanitarian class applicants experienced the longest processing times for their applications, followed by economic class applicants, and family class applicants.

For refugee and humanitarian class applicants, processing times increased between January 2022 and December 2022:

- In January and February 2022, the average processing time was 26 months.

- In March 2022, the average processing time decreased to 24 months.

- In April 2022, the average processing time increased to 29 months.

- In May 2022, the average processing time decreased to 27 months.

- In June 2022, the average processing time decreased to 26 months and remained at that rate for July.

- In August 2022, the average processing time increased to 29 months.

- In September 2022, the average processing time increased to 30 months and remained at that rate for October and November.

- In December 2022, the average processing time increased to 32 months.

For economic class applicants, processing times decreased between January 2022 and December 2022:

- In January 2022, the average processing time was 23 months.

- In February 2022, the average processing time decreased to 20 months and remained at that rate for March.

- In April 2022, the average processing time decreased to 19 months and remained at that rate for May.

- In June 2022, the average processing time decreased to 18 months and remained at that rate for July, August, and September.

- In October 2022, the average processing time decreased to 17 months.

- In November 2022, the average processing time decreased to 16 months.

- In December 2022, the average processing time decreased to 15 months.

For family class applicants, processing times decreased between January 2022 and December 2022:

- In January 2022, the average processing time was 13 months.

- In February 2022, the average processing time increased to 14 months and remained at that rate for March, April, and May.

- In June 2022, the average processing time decreased to 13 months and remained at that rate for July and August.

- In September 2022, the average processing time decreased to 12 months and remained at that rate for October and November.

- In December 2022, the average processing time decreased to 10 months.

9.19 Despite meeting the overall admission target and improved processing times in its economic class and family class programs, we found that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada did not meet its service standards for the majority of applications in 2022 for the programs we examined (Exhibit 9.5).

Exhibit 9.5—In 2022, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s performance fell short of its service standards

Economic Class

| Class and program | Number of applications finalized and average processing time | Service standards | Percentage of applications processed within service standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Skilled Worker Program | 56,232—22 months | 6 months | 3% |

| Quebec-Selected Skilled Worker Program | 48,652—21 months | 11 months | 30% |

| Provincial Nominee Program (Non‑Express Entry) | 60,383—19 months | 11 months | 14% |

| Provincial Nominee Program (Express Entry) | 63,805—11 months | 6 months | 44% |

Family Class

| Class and program | Number of applications finalized and average processing time | Service standards | Percentage of applications processed within service standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overseas Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner Program | 44,239—15 months | 12 months | 56% |

| Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada Program | 37,618—11 months | 12 monthsNote * | 71% |

Refugee and Humanitarian Class

| Class and program | Number of applications finalized and average processing time | Service standards | Percentage of applications processed within service standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government-Assisted Refugees Program | 16,354—26 months | 12 monthsNote * | 26% |

| Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program | 31,494—30 months | 12 monthsNote * | 5% |

Note: Processing times were shorter on average for applicants residing in Canada.

Source: Based on information and data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

9.20 We also found that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada did not consistently process applications on a first‑in‑first‑out basis contrary to its operating principle. In 2022, newer applications were finalized ahead of older ones in all 8 programs we examined. For example, in the family class, more than 21,000 applications were finalized within 6 months of being received, ahead of at least 25,000 older applications that remained in the inventory at the end of the year. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s own analysis also found that the lack of adherence to this principle occurred across programs, and it identified operational pressure to finalize large volumes of applications to meet the Immigration Levels Plan as a key contributing factor.

9.21 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has experienced long‑standing challenges in meeting its service standards for its permanent resident programs. When the department last reviewed its service standards for processing applications in 2019, it identified that some needed to be updated considering the increased application volumes. However, we found that none had been reviewed or updated.

9.22 Service standards for processing times were not in place for refugee applications, contrary to Treasury Board directives that require any identified service to have a service standard. The department identifies both of the refugee programs we examined as services, but it had no plan to set service standards as required.

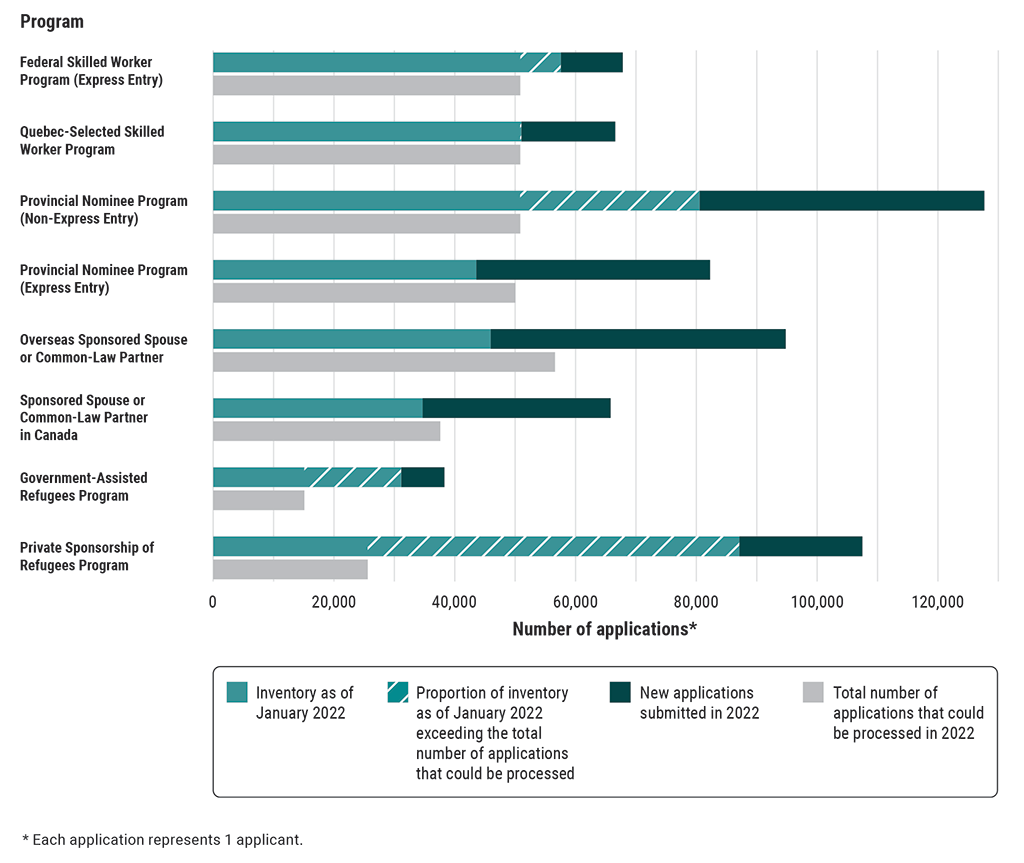

9.23 The department’s ability to meet service standards is also affected by the size of the application inventory relative to admission targets. From March 2020 through 2021, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada continued to accept applications to its permanent resident programs. But with office closures and travel restrictions, the volume of applications in its inventory grew. At the start of 2022, the volume of applications in the inventory for the majority of programs we examined already exceeded the number of applications that could be processed to meet admission targets (Exhibit 9.6).

Exhibit 9.6—At the start of 2022, inventory volumes exceeded the number of applications that could be processed for the majority of programs

Source: Based on data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Exhibit 9.6—text version

This chart compares the inventory volumes with the number of applications that could be processed for 8 permanent resident programs as of January 2022. The chart also shows the number of new applications submitted in 2022. Each application represents 1 applicant.

As of January 2022, for 5 out of 8 permanent resident programs, the number of applications in the inventory exceeded the number of applications that could be processed. The greatest difference between the number of applications in the inventory and the number that could be processed was for the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program, followed by the Provincial Nominee Program (Non‑Express Entry), the Government-Assisted Refugees Program, the Federal Skilled Worker Program (Express Entry), and the Quebec-Selected Skilled Worker Program.

The inventory grew in 2022. The 4 provincial nominee and sponsored spouse programs received the greatest number of applications, and some of these programs received as many or almost as many applications as they had as of January 2022.

For the Federal Skilled Worker Program (Express Entry), 50,850 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 57,570 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the number of applications exceeded the total number of applications that could be processed by 6,720. There were 10,251 new applications submitted in 2022.

For the Quebec-Selected Skilled Worker Program, 50,600 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 51,038 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the number of applications exceeded the total number of applications that could be processed by 438. There were 15,526 new applications submitted in 2022.

For the Provincial Nominee Program (Non‑Express Entry), 59,100 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 80,530 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the number of applications exceeded the total number of applications that could be processed by 21,430. There were 47,149 new applications submitted in 2022.

For the Provincial Nominee Program (Express Entry), 50,045 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 43,560 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the total number of applications that could be processed exceeded the number of applications by 6,485. There were 38,707 new applications submitted in 2022.

For the Overseas Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner, 56,600 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 45,939 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the total number of applications that could be processed exceeded the number of applications by 10,661. There were 48,855 new applications submitted in 2022.

For the Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada, 37,600 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 34,687 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the total number of applications that could be processed exceeded the number of applications by 2,913. There were 31,110 new applications submitted in 2022.

For the Government-Assisted Refugees Program, 15,100 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 31,141 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the number of applications exceeded the total number of applications that could be processed by 16,041. There were 7,135 new applications submitted in 2022.

For the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program, 25,600 applications could be processed in 2022. There were 87,117 applications as of January 2022. This meant that as of January 2022, the number of applications exceeded the total number of applications that could be processed by 61,517. There were 20,361 new applications submitted in 2022.

9.24 The minister has authority to apply intake controlsDefinition 5 through the issuance of Ministerial Instructions for permanent resident programs (excluding overseas refugees). During 2022, no instructions were issued to apply intake controls under this authority for the programs we examined. Recent legislative amendments (as of June 2023) also allow the use of Ministerial Instructions to limit intake of private sponsorship of refugee applications. Also, for its Express Entry programs, the department has the authority to limit the number of applications submitted through intake controls. For example, during 2022, the department applied intake controls for the Federal Skilled Worker Program to reduce inventories and backlogs and position its return to meeting its service standard for new applicants.

9.25 In addition to its service standards, in March 2022, the department began providing the expected processing times online for many of its permanent resident programs. However, this information was calculated using the wait times experienced by applicants whose files had been finalized within the preceding 6 months. It did not consider the volumes of applications that had been received or were backlogged, both of which significantly influence expected processing times.

9.26 To provide applicants with clear expectations of the likely timelines for a decision, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should establish achievable and reliable service standards for the processing of permanent resident applications, including for its refugee programs. In addition, online information on expected processing times should be provided for all permanent resident applications and consider the volume and age of applications already in its inventories.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Persistent backlogs, particularly for refugee programs

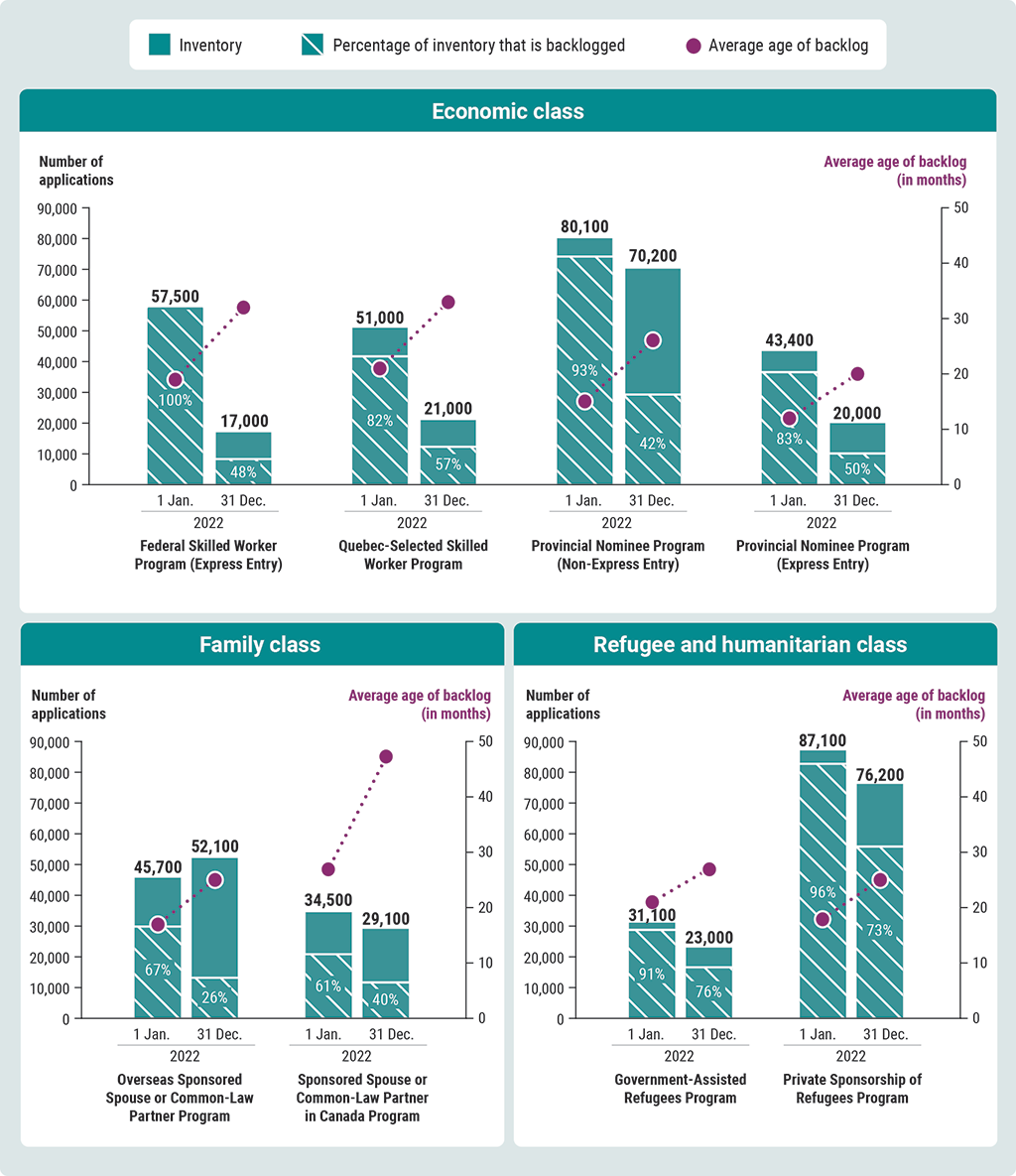

9.27 We found that in 2022, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada succeeded in reducing the number of backlogged applications in both its economic class and family class programs. For example, in the Federal Skilled Worker Program (an economic class program), the number of backlogged applications fell to 8,200 in December 2022 from 57,500 in January 2022 (Exhibit 9.7).

Exhibit 9.7—Large and aging application backlogs persisted across permanent resident programs—more than half of the applications remained backlogged at the end of 2022

Source: Based on data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Exhibit 9.7—text version

This chart shows the application inventory, the backlogs, and the average age of the backlogs from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2022 for 8 permanent resident programs.

In all 8 programs, the average age of the backlogged applications increased. Although the percentage of backlogged applications decreased from January to December in all 8 programs, more than half of the applications remained backlogged at the end of 2022.

The following are the details for economic class programs:

- For the Federal Skilled Worker Program (Express Entry), there were 57,500 applications in both the inventory and the backlog as of January 1. This means that 100% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 19 months. As of December 31, there were 17,000 applications in the inventory and 8,210 applications in the backlog. This means that 48% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 32 months.

- For the Quebec-Selected Skilled Worker Program, there were 51,000 applications in the inventory and 41,565 in the backlog as of January 1. This means that 82% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 21 months. As of December 31, there were 21,000 applications in the inventory and 12,077 applications in the backlog. This means that 57% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 33 months.

- For the Provincial Nominee Program (Non‑Express Entry), there were 80,100 applications in the inventory and 74,511 in the backlog as of January 1. This means that 93% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 15 months. As of December 31, there were 70,200 applications in the inventory and 29,532 applications in the backlog. This means that 42% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 26 months.

- For the Provincial Nominee Program (Express Entry), there were 43,400 applications in the inventory and 36,104 in the backlog of January 1. This means that 83% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 12 months. As of December 31, there were 20,000 applications in the inventory and 9,932 applications in the backlog. This means that 50% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 20 months.

The following are the details for family class programs:

- For the Overseas Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner Program, there were 45,700 applications in the inventory and 30,521 in the backlog of January 1. This means that 67% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 17 months. As of December 31, there were 52,100 applications in the inventory and 13,411 applications in the backlog. This means that 26% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 25 months.

- For the Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada Program, there were 34,500 applications in the inventory and 21,202 in the backlog of January 1. This means that 61% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 27 months. As of December 31, there were 29,100 applications in the inventory and 11,776 applications in the backlog. This means that 40% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 47 months.

The following are the details for refugee and humanitarian class programs:

- For the Government-Assisted Refugees Program, there were 31,100 applications in the inventory and 28,420 in the backlog of January 1. This means that 91% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 21 months. As of December 31, there were 23,000 applications in the inventory and 17,434 applications in the backlog. This means that 76% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 27 months.

- For the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program, there were 87,100 applications in the inventory and 83,940 in the backlog of January 1. This means that 96% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog was 18 months. As of December 31, there were 76,200 applications in the inventory and 55,700 applications in the backlog. This means that 73% of the applications in the inventory were backlogged. The average age of the backlog had increased to 25 months.

9.28 Although the department reduced the number of backlogged applications, we found that a substantial number of applications across all programs remained backlogged at the end of 2022. The department aims to process 80% of applications within its service standards. However, the volume of applications that remained backlogged at the end of 2022 far exceeded 20% in all programs. For example, for the Provincial Nominee Program (Express Entry), Exhibit 9.7 shows that at the start of 2022, 83% of applications were backlogged, and at the end of the year, 50% were backlogged.

9.29 We also found that the age of backlogged applications increased across all programs, indicating that the department finalized many newer applications over older ones. For example, in the Provincial Nominee program (Express Entry), the age of applications remaining in the backlog had increased from 12 to 20 months, while in the Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada Program, the age rose from 27 to 47 months.

9.30 Furthermore, we found that the department made little progress in reducing its aging backlogs in the refugee programs we examined. Refugees continued to face the longest average wait times among all 3 permanent resident classes. At the end of 2022, about 99,000 refugee applications were still waiting to be processed, and many applicants will wait years for a decision in the current processing environment. The department’s ability to reduce backlogs in these programs is limited by the number of refugee program admissions allowed under the Immigration Levels Plan. For example, at the beginning of 2022, the number of applications to the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program waiting to be processed was already 3 times higher than the number of refugees the department could admit that year, and it received 20,000 new applications. The combined effect limits the department’s ability to reduce its aging backlog (see Exhibit 9.6).

9.31 We also found differences in the size and age of application backlogs by country of citizenship in 7 of the 8 permanent resident programs we examined. These differences were most prevalent in the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program, the Federal Skilled Worker Program, and the Overseas Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner Program.

9.32 For example, in the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program, more than half of the applications submitted by citizens of Somalia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo were backlogged. In comparison, only one third of the applications submitted by citizens from Syria were backlogged. These 3 countries had the highest volumes of applications submitted under the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program. The limited capacity in offices tasked with processing these applications was a contributing factor. (See paragraphs 9.44 to 9.53 for further details).

9.33 Because refugee applicants reside outside their countries of citizenship, the conditions in the countries where they reside also affect the processing of their applications. Department officials told us that processing time can be longer for some applicants because of conditions unique to their country of residence—for example, an officer’s inability to conduct interviews in remote or dangerous locations. Applicants may also encounter delays in obtaining the necessary documents, such as a medical exam, to support their application. We noted that some offices developed solutions to help overcome these challenges, such as screening tools to determine whether interviews were actually required or arranging for virtual interviews (when Internet and interpretation services were available).

9.34 We also found that the department did not track or analyze application processing times or backlogs by country of citizenship. It used a gender‑based analysis plusDefinition 6 assessment to understand the gender composition of new admissions, but this analysis did not look for differential outcomes in processing times on the basis of gender or other intersecting identity factors, such as race or citizenship or country of residence.

9.35 In 2021, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada committed to identifying and addressing systemic discrimination and barriers in its policies, programs, and initiatives. Its Anti‑Racism Strategy 2.0 (2021–2024) outlined its commitment to identify and address differential outcomes for applicants, including the use of race‑based and ethnocultural information to assess disparities in processing times. We found that the department does not collect information from applicants in a manner that allows it to identify such disparities. Furthermore, the department had no plans or timelines in place to do so, despite its Anti‑Racism Strategy commitment to monitor for differential outcomes by 31 March 2024.

9.36 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should take immediate steps to identify and address differential wait times to support timely processing for all applicants across permanent resident programs, as it works within the annual admission targets set by the Immigration Levels Plan. Furthermore, it should develop and implement a plan to collect race‑based and ethnocultural information from applicants directly in order to address any racial disparities in wait times.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Frequently stalled applications

9.37 We found that backlogged applications often experienced multiple delays with long periods of inactivity from the time they were submitted. Applications were frequently delayed for a number of reasons (Exhibit 9.8). Although some of these were under applicants’ control (such as taking a long time to submit requested information or documents), we found that 4 of the 5 most frequent reasons for delays stemmed from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s inventory management practices. On average, each delay stalled applications by 4 months to a year or more.

Exhibit 9.8—Four of the top 5 factors contributing to processing delays were under the department’s control

| Reason for delay | Application stage (see Exhibit 9.3) |

Percentage of applications affectedNote * |

|---|---|---|

| Waiting for document verification and preparation for eligibility assessment by the department | Document verification and preparation | 53% |

| Waiting for eligibility assessment by the department | Eligibility assessment | 50% |

| Delays by departmental officers in requesting additional information or in conducting interviews to determine eligibility | Eligibility assessment | 21% |

| Waiting for additional information requested from applicants | Eligibility assessment | 17% |

| Waiting for departmental officer to assess admissibility | Admissibility assessment | 15% |

Source: Based on a representative sample of 408 applications (across 8 permanent resident programs) whose age ranged from 6 months to more than 4 years from the date submitted. Percentages take into account the different volumes of applications in each of the 8 programs.

9.38 Across all programs, applications frequently waited in the queue before the initial processing even began. This caused the longest delays for refugee applicants: We found that these applications sat untouched for 15 to 20 months (on average) before being prepared for an initial eligibility assessment. Application delays in economic and family class programs ranged from 4 to 10 months (on average).

9.39 We also found that delays occurred frequently throughout 2022, even after backlogged applications were opened to assess eligibility. We found that at this stage, officers were often slow to request required information from applicants and to assess what had been received.

9.40 Under permanent resident admission targets, officers finalize a fixed number of applications each year. Additionally, officers may be reassigned to other programs or priorities, resulting in delays for some applications in progress. We note that a delay increased the likelihood that documentation would be needed to process an application, causing further delays. For example, in more than one third of the backlogged applications we examined, we found that applicants’ immigration medical exams had expired. (This problem was particularly prevalent in family class programs for overseas family members.)

9.41 Some delays occurred for reasons outside the department’s control, such as the need to wait for information from applicants or decisions from security partners. Security‑related delays occurred in about 5% of the applications in our sample.

9.42 To direct applications through processing, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada uses a series of electronic file codes, including the identification codes of former employees. We examined nearly 6,000 applications for permanent residence and found that 57 (about 1%) were assigned to codes of former employees. All were delayed as a result, with delays ranging from 4 to 22 months. We brought these applications to the department’s attention, and all were reassigned by the end of our audit. We did not find that the department’s use of other electronic file codes caused other delays.

9.43 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should examine backlogged applications to identify and action processing delays within its control, including waiting for officer actions or follow‑up. The department should also prioritize the finalization of older backlogged applications while working to achieve the annual admission targets set by the Immigration Levels Plan.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Despite increased resources, backlogs persisted in some offices

9.44 This finding matters because Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s efforts to improve processing and reduce backlogs should benefit program applicants regardless of the office where their application is sent for processing.

9.45 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has approximately 2,600 staff processing applications for permanent residence in 87 offices located in Canada and abroad. Each office is assigned a target number of applications to process each year on the basis of the volume of applications submitted in its assigned geographic region. Under the department’s resourcing plan, office capacity is meant to match assigned processing volumes. An applicant’s location at the time of submission determines the office where their application is sent for processing. All offices are subject to the same service standards for processing applications. The department relies on short‑term measures, like temporary assignments and overtime work, to supplement capacity when needed.

Different processing capacities in different offices

9.46 We found that some applicants experienced longer wait times than others because of the office where their application was sent for processing. In 2022, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada received additional funding to improve processing times and reduce backlogs, and it hired nearly 1,000 new employees across its processing offices. However, we still found large variations in processing times and backlogs by office.

9.47 We found that backlogs accumulated in some offices in Canada and abroad that had fewer staff to process applications. For example, almost half of the backlogged applications to the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program and the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program were in the Nairobi (Kenya) and Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) offices. However, even with additional temporary officers in 2022, the Nairobi office had about half the staff but almost double the assigned workload of the Ankara (Turkey) office. Similarly, the Dar es Salaam office had a comparable number of staff but 5 times the assigned workload of the Rome (Italy) office.

9.48 The department recognized that its offices in sub‑Saharan Africa were chronically under‑resourced. Nevertheless, it continued to assign its sub‑Saharan African offices some of the highest processing volumes for family and refugee programs, and it had no immediate plan to resolve the high levels of backlogged applications and longer wait times for these applicants.

9.49 With digital applications, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada can redistribute aging applications to offices with available capacity to facilitate timelier processing. However, we found family class and refugee class applications were not transferred out of the Dar es Salaam or Nairobi offices—which both have high workload and application backlogs. Furthermore, department officials told us that they had no plans to transfer backlogged applications to other offices with available capacity, leaving these applicants to wait even longer.

9.50 We also found that offices in sub‑Saharan Africa were unable to meet some of their assigned targets for family and refugee programs in 2022, further disadvantaging applicants directed to those offices for processing. For example, in the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program, officials told us that other, better‑resourced offices, such as those in the Middle East, were asked to exceed their assigned targets with their own application workloads, in order to meet the Immigration Levels Plan.

9.51 In 2016, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada announced its transition to capacity‑based processing—whereby application workloads would be moved according to available capacity across its offices. The department identified this change as key to alleviating excess demand on some offices, decreasing regional disparities in processing times, and reducing backlogs. We found that the department did not transition to capacity‑based processing and continued to assign workloads to offices based on application volumes in their assigned geographical region, without regard to their available capacity to process these applications. As a result, regional backlogs continued to accumulate in the overseas family and refugee classes in some offices with limited capacity.

9.52 In addition, we found fundamental gaps in the department’s information about the processing capacity within its offices: The department did not know whether these offices had the resources they needed to process the volumes of applications assigned to them. In our opinion, the department cannot move to effective capacity‑based processing without reliable information on where capacity exists. At the time of our audit, the department was still exploring options to track capacity by office to better support timely processing. It expected to begin this tracking in 2026—10 years after the department said that it had shifted to capacity‑based processing.

9.53 To improve consistency of application processing times across its offices, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should match assigned workloads with available resources, and it should support these decisions with reliable information on the available capacity within its offices. It should act immediately to address application backlogs that have accumulated in certain offices with limited capacity.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

New digital tools did not benefit programs or applicants evenly

9.54 This finding matters because new digital tools are meant to increase processing efficiency and reduce wait times for all program applicants. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should know whether its tools are working as intended, monitor for unintended negative effects on applicants, and reduce these effects when they arise.

9.55 Because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the department moved to a digital processing environment more quickly than anticipated. Its Digital Platform Modernization initiative—meant to help the department shift from paper‑based applications to using online portals and digital processing for all permanent resident applications—was planned for implementation by 2026. The closure of processing offices at the onset of the pandemic created the need to rapidly shift to online application submissions and processing. At the time, permanent resident programs outside of the Express Entry system were largely paper‑based.

9.56 In April 2021, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada launched the Permanent Residence Portal—an interim solution to allow applicants to submit their applications and documents electronically. The portal opened in select economic class and family class programs first. By October 2022, digital submission was mandatory for all applicants to all programs in these classes (with exceptions made for applicants unable to submit digitally). The department also converted most incoming paper applications and some existing paper‑based inventories to digital formats for processing. It had digitized more than 180,000 paper applications by early 2023.

9.57 To reduce processing times and backlogs, the department introduced an automated eligibility‑assessment tool in the Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada Program in April 2021. This tool uses established criteria to assess applicants’ and sponsors’ eligibility and triage applications into 2 categories. Applications that meet these criteria receive an automatic pass on the eligibility assessment and are moved forward for further processing. Those that do not meet the criteria are passed to an officer who conducts the eligibility assessment manually. In both cases, applications are reviewed manually for admissibility and final decisions are made by an officer.

9.58 The tool’s stated purpose is to allocate some of the time saved through automation to applications that require manual assessment to reduce overall wait times for all applicants. The department had already begun expanding the use of similar tools across other permanent resident programs, including the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program toward the end of our audit period in December 2022.

Differential wait times

9.59 In developing the automated eligibility‑assessment tool for the Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada Program, we found that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada assessed the results of the tool as required by Treasury Board’s Directive on Automated Decision‑Making. The department also conducted required impact mitigation exercises, including a peer review and a gender‑based analysis plus assessment, and established a quality assurance plan to verify that the tool produced the same decision that an officer would.

9.60 Using the tool to triage applicants into 2 groups—1 that automatically passed the eligibility assessment and 1 that would need an officer to conduct a manual eligibility assessment—was intended to not significantly or disproportionately affect applicants, as long as resources were reallocated to maintain roughly equal processing times across the 2 groups. However, once implemented, the department did not monitor whether the tool succeeded in reducing overall processing times for all applicants as intended.

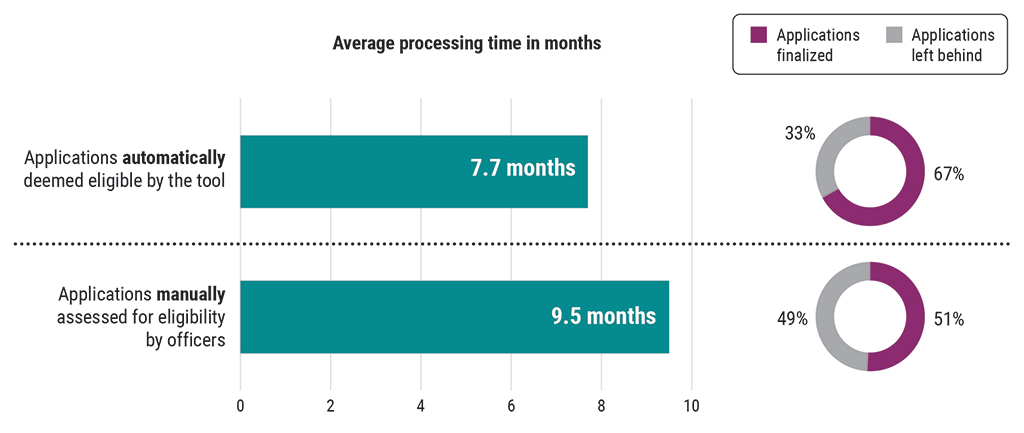

9.61 We found that applications that received an automated eligibility decision were finalized, on average, about 2 months faster than those that did not (Exhibit 9.9). The department was aware that, in order to meet increased admission targets, applications automatically deemed eligible by the tool were being finalized more quickly while those that were manually processed for eligibility were being left behind. However, it did not have a plan to reduce this differential impact to the extent possible.

Exhibit 9.9—Applications automatically deemed eligible were finalized faster than those that were not

Source: Based on data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Exhibit 9.9—text version

This chart shows the difference in processing times for applications that were automatically deemed eligible by the tool and those that were manually assessed for eligibility by officers. The processing time of applications that were automatically deemed eligible by the tool was about 2 months faster than those that were manually assessed for eligibility by officers.

Applications automatically deemed eligible by the tool were processed in an average of 7.7 months. This meant that 67% of applications were finalized and 33% were left behind.

Applications manually assessed for eligibility by officers were processed in an average of 9.5 months. This meant that 51% of applications were finalized and 49% were left behind.

9.62 We also found that applicants from certain countries of citizenship were directed to manual processing by the tool at higher rates and experienced longer than average processing times. For example, almost all applications from individuals with Haitian citizenship were routed to manual processing, and applicants waited twice as long for a final decision. At the same time, applications from other countries of citizenship, including India and South Korea, received automated eligibility decisions at higher rates and experienced faster than average processing times.

9.63 We note that applications that are sent to manual processing by the tool may be more complex because of country‑specific conditions, resulting in delays and longer processing times. However, the department had not examined the extent to which application complexity affects processing times, nor had it allocated sufficient additional resources to reduce the delays experienced by some groups of applicants.

9.64 To support timely processing for all applicants, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should examine differential outcomes in processing times related to the implementation of automated decision‑making tools and reduce these disparities to the extent possible, including by reallocating sufficient resources to applications directed to manual processing.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Access to online portals to shorten processing times not available to applicants in refugee programs

9.65 We found that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada expanded access to online application portals across 20 permanent resident programs in 2021 and 2022. Previously, only applicants to the 4 programs in the Economic Class’s Express Entry system could submit their applications through an online portal. We found that the benefits of this transition to online portals began to be realized in 2022. For example, in the Provincial Nominee Program (Non‑Express Entry), we found that applications submitted through the portal in early 2022 were more likely to be finalized within the year than those submitted in paper form.

9.66 However, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada did not implement an online portal for its refugee programs. Most applications for these programs are submitted electronically by unsecure email and entered into the department’s processing system manually, presenting privacy and security risks and inefficiencies. The department first identified the need for an online application portal to address these concerns in 2016; however, solutions were repeatedly delayed because of shifting priorities within the department. By the end of our audit, an online portal for the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program was planned for launch in late 2023. An online application portal for all Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada services, including the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program, is planned for the end of 2024 under the department’s Digital Platform Modernization initiative.

9.67 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should implement without further delay online application portals for its refugee programs, while also working to complete its Digital Platform Modernization initiative.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

9.68 We concluded that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada improved the processing of permanent resident applications in 2022 but was still far from meeting its service standards for prompt processing. Across the programs we examined, the department reduced the volume of backlogged applications that had accumulated over the course of the pandemic, but a significant backlog remained.

9.69 Despite receiving additional resources in 2022 to improve overall processing times and reduce backlogs, processing offices in some regions continued to face significant backlogs.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on how efficiently and promptly Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada processes applications to its permanent resident programs. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the department complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada processed applications for permanent residence in a prompt and efficient manner to support Canada’s economic, family reunification, and humanitarian objectives.

Scope and approach

This audit focused on how promptly and efficiently Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada processed applications for 8 permanent resident programs. We reviewed the department’s approach to inventory management and its efforts to reduce processing times for applicants while maintaining program integrity. We also reviewed the strategies it implemented to address processing delays that stemmed from the COVID‑19 pandemic. Using data obtained from the department’s case processing system, we quantified the results of the department’s efforts, including to what extent it reduced existing backlogs and improved processing times during 2022.

We also reviewed the department’s processing capacity and workload distribution across its offices and programs. This included examining the commitments it made in 2021 to hire new staff to address backlogs and its ongoing transition to online application portals and other digital tools to improve processing efficiency.

We also examined differential outcomes in processing times and backlogs according to applicant country of citizenship. This included examining processing outcomes from the department’s overseas and inland offices by region and the effects of automated decision‑making tools on applicants from different parts of the world.

Our audit included an in‑depth file review of a representative sample of backlogged applications from our 8 programs of focus (408 files in total). As part of this file review, we examined the reasons for processing delays and whether the delays were within or beyond the department’s control. Where representative sampling was used, samples were sufficient in size to conclude on the sampled population with a confidence level of no less than 90% and a margin of error of no greater than +10%.

Our 8 programs of focus included the following 4 economic class programs:

- Federal Skilled Worker Program (Express Entry)

- Quebec-Selected Skilled Worker Program

- Provincial Nominee Program (Express Entry)

- Provincial Nominee Program (Non‑Express Entry)

We looked at the following 2 family class programs:

- Overseas Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner Program

- Sponsored Spouse or Common‑Law Partner in Canada Program

We looked at the following 2 refugee and humanitarian class programs:

- Government-Assisted Refugees Program

- Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program

The audit did not examine any other permanent resident programs in depth. Collectively, the 8 programs we examined represented more than 50% of the total volume of applications in the permanent resident program inventories in 2022.

We did not examine temporary resident programs administered by the department.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada processes permanent resident applications in a prompt and efficient manner while maintaining program integrity. |

|

|

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada manages processing capacity in its networks and programs to facilitate the prompt and efficient processing of permanent resident applications. |

|

|

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s transition to online processing and its use of digital tools facilitates the prompt and efficient processing of permanent resident applications while maintaining program integrity. |

|

|

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada conducts analysis to identify and address inequities or differential outcomes on diverse groups in its processing of permanent resident applications. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January to 31 December 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters outside of these dates. These include strategies used by the department in 2020 and 2021 to adapt its application processing operations to the realities of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the processing work it did into 2023 on certain files included in our review.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 1 September 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Carol McCalla, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

9.26 To provide applicants with clear expectations of the likely timelines for a decision, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should establish achievable and reliable service standards for the processing of permanent resident applications, including for its refugee programs. In addition, online information on expected processing times should be provided for all permanent resident applications and consider the volume and age of applications already in its inventories. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has plans for a comprehensive multi‑year service standard review, in accordance with the requirements of the Government of Canada’s Policy on Service and Digital. This review will prioritize establishing service standards for services that currently have none. This includes permanent residence streams, such as the federal and regional economic class, family class, and resettled refugee immigration programs. Completion of this first phase is expected by the end of the 2024–25 fiscal year. The department will evaluate existing service standards to ensure they are comprehensive, meaningful, and relevant. Published processing times are historical, meaning they are measured based on how long it took to process 80% of applications in the past 6 months. While the department is currently publishing those backward‑looking processing times, new methodologies have been developed in order to calculate forward‑looking estimates of processing times. This will allow the department to provide clients with more accurate expected wait times, accounting for volume and inventory after clients have submitted their applications. |

|

9.36 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should take immediate steps to identify and address differential wait times to support timely processing for all applicants across permanent resident programs, as it works within the annual admission targets set by the Immigration Levels Plan. Furthermore, it should develop and implement a plan to collect race‑based and ethnocultural information from applicants directly in order to address any racial disparities in wait times. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada endeavours to process all applications in a timely manner. Applications are assessed on a case‑by‑case basis. As a result, differences in wait times are unavoidable. In addition, new commitments to specific populations may displace the processing of applications submitted and awaiting processing. However, the department will monitor wait times and include an examination and analysis of any differential findings observed. The department will develop and implement a pilot to begin testing ways of collecting race‑based and ethnocultural information from its applicants, on a voluntary and self‑reported basis. The pilot will allow the department to test methodologies and gather insights about the best ways to collect, analyze, and use race‑based and ethnocultural data in line with the department’s Anti‑Racism Strategy. The pilot will inform critical aspects of the approach in terms of data integrity, standards, ethics, analysis, and privacy safeguards. As this data would be voluntary and on a self‑reported basis, the department will assess its sample size and determine whether any bias exists in the sample size. This will be crucial to determine how to use the information collected and is directly related to the need for the department to establish and find a robust methodology that allows for both representativeness and the ability to isolate specific factors that may influence processing. Only then can the department analyze the data and identify findings. Such findings will then be integrated into the department’s broader work on examining racism in its policies and programs. The estimated timeline for launching the collection of the data on a voluntary and self‑reported basis will align with broader department efforts on standardizing how it collects disaggregated data. |

|

9.43 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should examine backlogged applications to identify and action processing delays within its control, including waiting for officer actions or follow‑up. The department should also prioritize the finalization of older backlogged applications while working to achieve the annual admission targets set by the Immigration Levels Plan. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada determines the number of admissions for the year within each immigration category and establishes priorities among economic, social, and humanitarian objectives with the annual Immigration Levels Plan. The department receives more applications within many categories than can be processed based on the Immigration Levels Plan. Intake controls exist for permanent resident lines of business where applications are submitted via the Express Entry system. However, intake controls do not exist in most other permanent resident programs, which led to the formation of backlogs. The department will continue to process applications (while respecting the annual Immigration Levels Plan) to address the backlogs where they exist in permanent resident programs. The department will also work on an implementation plan for the new authorities received to control intake within the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program. A department‑wide approach across permanent resident programs will better enable the department to prevent and reduce backlogs at the program level. Where regional backlogs exist, the department will continue to improve on its existing workload monitoring and workload sharing tools to identify files that can be shifted to other offices and/or ensure that supplementary resources are allocated. |

|

9.53 To improve consistency of application processing times across its offices, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should match assigned workloads with available resources, and it should support these decisions with reliable information on the available capacity within its offices. It should act immediately to address application backlogs that have accumulated in certain offices with limited capacity. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada will review and work to improve its workload monitoring and workload sharing tools to permit the department to better identify where capacity challenges exist and continue to manage workloads and reduce backlogs where possible (where space allows according to the Immigration Levels Plan). The department began shifting from paper‑based processing and accelerated digital processing during the COVID‑19 pandemic. This approach enabled the department to reallocate certain economic class and temporary resident workloads to align with available capacity. Shifting capacity around the processing network is possible in many areas and allows offices to focus on caseloads whereby place‑based expertise is required. Most refugee and many family class applications require in‑person interviews and an advanced understanding of the local conditions, customs, and regulations, and therefore, require additional resources to be in place. The department augments in office capacity with temporary duty assignments and work‑sharing with other offices. Additionally, the department implemented a new team with resettlement expertise to provide surge capacity and supplementary processing support to missions with aging inventories, allowing for a responsive approach to shifting inventories in 2022. While these efforts were insufficient in 2022, the above solutions have been successfully leveraged at a higher rate in 2023 and will be expanded in 2024 to further reduce regional backlogs and disparity in regional processing times for refugees by the end of 2024. Due to regional complexities (client mobility rights, security conditions, exit permissions, and so on) and/or the prioritization of cohorts in response to emerging crises, there will always be some level of variance in application processing times in a resettlement context despite these efforts. |

|

9.64 To support timely processing for all applicants, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should examine differential outcomes in processing times related to the implementation of automated decision‑making tools and reduce these disparities to the extent possible, including by reallocating sufficient resources to applications directed to manual processing. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada commits to monitoring and evaluating the effects of automated decision making on overall processing times for clients selected for automated and manual processing. However, full alignment is not expected or possible given that non‑automated cases tend to be more complex and require additional efforts to process for various reasons (for example, additional documents from applicants, checks with partners, and so on). The implementation of automated decision‑making tools for application triage and eligibility assessment has led to efficiencies in both of these processing steps, regardless of the country of origin. Based on these efficiencies, the department will reallocate resources to areas where additional capacity is required once further analysis has been conducted, as the efficiency gains are still relatively new. It is also important to note that country‑specific conditions and external factors beyond the department’s control will continue to have an impact at the eligibility and admissibility stages of applications. (Note: Automated decision‑making tools are not being applied at the admissibility stage.) As the department’s automated decision‑making capacity matures, new measures will be established to support normalization within lines of business through new capacity allocation models, the aim being to ensure that processing times align with established service standards for each line of business regardless of how an application was triaged and processed by an automated decision‑making tool. |

|

9.67 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada should implement without further delay online application portals for its refugee programs, while also working to complete its Digital Platform Modernization initiative. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada is on track to add the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program and the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program (non‑United Nations High Commission for Refugees referrals) to its permanent resident online portal in October and November 2023 respectively. Over 2022, Commission‑referred applications under the Government‑Assisted Refugees Program begun being submitted electronically to the department through an encrypted SharePoint submission, which protects the personal information of clients. |