2023 Reports 6 to 10 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 7—Departmental Progress in Implementing Sustainable Development Strategies—Zero-Emission Vehicles

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Despite some contributions, the government is unlikely to meet its target of 80% of vehicles in the federal administrative fleet being zero‑emission vehicles by 2030

- Selected federal organizations had limited reporting on how their results related to zero‑emission vehicles contributed to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 12

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Appendix—Organizations Subject to the Federal Sustainable Development Act

- Exhibits:

- 7.1—The 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy and expectations for contributions by departmental strategies

- 7.2—Types of vehicle powertrain technologies, according to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- 7.3—As of 31 March 2022, most vehicles in the largest federal administrative fleets were powered by internal combustion engines

- 7.4—Some percentages of vehicle purchases that were zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles did not meet the short‑term milestone of 75%

- 7.5—Percentages of zero‑emission vehicles in federal administrative fleets were well below the government’s 2030 target of 80%

Introduction

Background

7.1 Under the Federal Sustainable Development Act, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change is required to develop a federal sustainable development strategy at least every 3 years. The strategy outlines the Government of Canada’s plan and vision for a more sustainable Canada over the 3‑year period. It further establishes government‑wide environmental and sustainable development goals, targets, and contributing actions.

7.2 The act also requires designated federal organizations (listed in the Appendix) to

- prepare their own sustainable development strategies that contain objectives and plans

- ensure that these strategies comply with the federal strategy and contribute to meeting its goals

- report on progress in implementing their sustainable development strategies at least once in each of the 2 years following the tabling in Parliament of their strategies

Organizations not listed in the act may also report voluntarily.

7.3 The federal sustainable development strategy subject to this audit covered the period from 2019 to 2022. Twenty‑seven federal organizations were required to table departmental sustainable development strategies to contribute to the federal strategy (Exhibit 7.1).

Exhibit 7.1—The 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy and expectations for contributions by departmental strategies

2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy

| Federal goals | The 13 federal goals in the strategy are long‑term aspirational results that reflect the government’s priorities for sustainable development. |

| Federal targets | The federal strategy contains 32 targets, which are medium‑term objectives that contribute to achieving the 13 federal goals. Each goal must have at least 1 target, and each target must have at least 1 indicator to track progress. |

| Federal contributing actions | There are also 68 contributing actions in the federal strategy that set out what the federal government will do to achieve the federal goals and targets. |

2020–2023 departmental sustainable development strategies

| Departmental actions | Certain federal organizations (or their presiding ministers, as applicable) have to develop their own departmental sustainable development strategies, which articulate their contributions to the federal strategy. Departmental actions in departmental strategies are concrete activities with objectives that individual organizations undertake to support the federal contributing actions and help to achieve the federal goals and targets. |

7.4 Under the Auditor General Act, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development monitors and reports on the progress of designated federal organizations toward sustainable development. This is a continually evolving concept that integrates social, economic, and environmental concerns. The Commissioner also has a duty to monitor and report on progress made by federal organizations that are subject to the Federal Sustainable Development Act. In particular, the Commissioner monitors and reports on the extent to which

- these organizations have contributed to meeting the targets in the federal strategy

- these organizations have met the objectives and implemented the plans in their departmental strategies

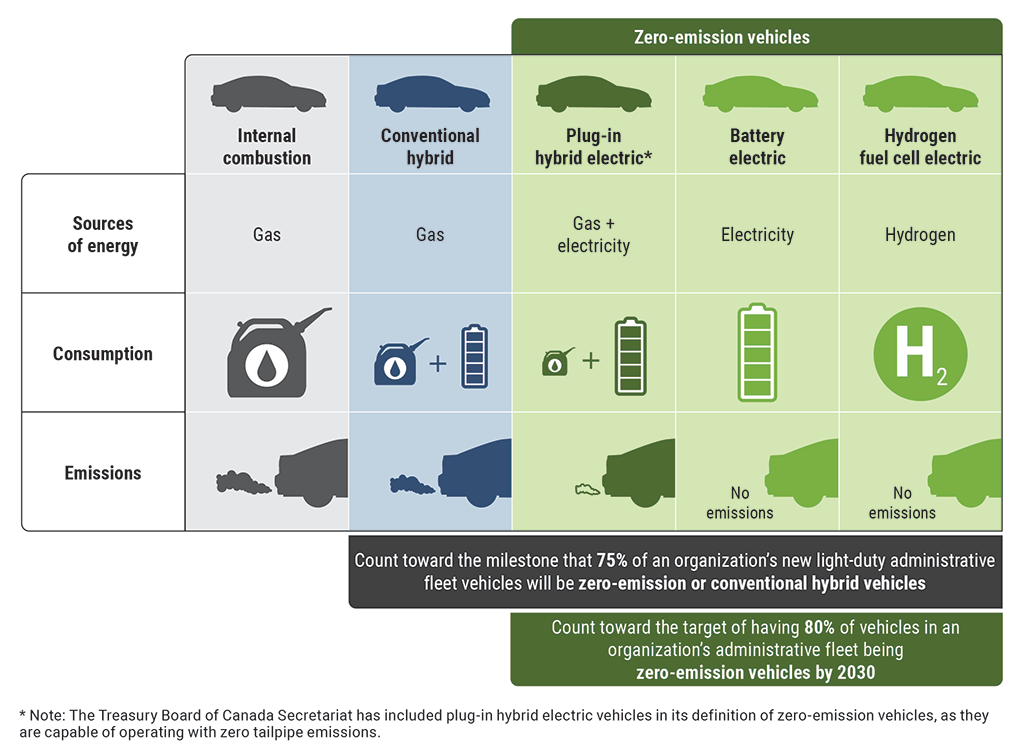

7.5 This audit is about the contribution of federal organizations under the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy reporting cycle. This year’s report on departmental progress in implementing sustainable development strategies focuses on federal organizations’ contributions to meeting the target of 80% zero‑emission vehicles in the federal administrative fleetDefinition 1 by 2030.

7.6 Different categories of vehicles run on a variety of technologies and have a vast range of carbon footprints (Exhibit 7.2). The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat has defined zero‑emission vehicles that count toward the target as those that can operate without producing tailpipe emissions, including plug‑in hybrid electric, battery electric, and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles. Other hybrid electric vehicles are not considered zero‑emission vehicles, as they have smaller batteries, which cannot be plugged in and charge with electricity generated by the vehicle’s combustion engine and brakes. This report refers to those vehicles as “conventional hybrid vehicles,” to distinguish them from plug‑in hybrid electric vehicles.

Exhibit 7.2—Types of vehicle powertrain technologies, according to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Source: Adapted from information from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Exhibit 7.2—text version

This illustration shows 5 types of vehicle powertrain technologies and their sources of energy, their consumption, and their amounts of emissions.

The first type is internal combustion technology. The source of energy for an internal combustion vehicle is gas. This vehicle consumes gas, and it emits a large amount of emissions.

The second type is conventional hybrid technology. The source of energy for a conventional hybrid vehicle is gas. This vehicle consumes gas and electricity, and it emits a moderate amount of emissions.

The last 3 types are the plug‑in hybrid electric, battery electric, and hydrogen fuel cell electric technologies. Vehicles that use these technologies are considered zero‑emission vehicles.

The sources of energy for a plug‑in hybrid electric vehicle are gas and electricity. This vehicle consumes gas and electricity, and it emits almost no emissions. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat has included plug‑in hybrid electric vehicles in its definition of zero‑emission vehicles, as they are capable of operating with zero tailpipe emissions.

The source of energy for a battery electric vehicle is electricity. This vehicle consumes electricity, and it emits no emissions.

The source of energy for a hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle is hydrogen. This vehicle consumes hydrogen, and it emits no emissions.

Conventional hybrid vehicles and the 3 zero‑emission vehicles—that is, plug‑in hybrid electric, battery electric, and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles—count toward the milestone that 75% of an organization’s new light‑duty administrative fleet vehicles will be zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles.

The 3 zero-emission vehicles—that is, plug‑in hybrid electric, battery electric, and hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles—count toward the target of having 80% of vehicles in an organization’s administrative fleet being zero‑emission vehicles by 2030.

7.7 Under the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, 27 federal organizations were responsible for preparing departmental sustainable development strategies. These strategies must contain actions that would contribute to meeting the goal of transitioning to low‑carbon, climate-resilient, and green operations, including to meeting the target of administrative fleets comprising at least 80% zero‑emission vehicles by 2030. These organizations are also responsible for reporting on their progress at least once in each of the 2 years following the tabling of their strategies in Parliament. Among these, we examined the 4 organizations with the largest fleets of administrative vehicles:

- National Defence

- Parks Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Canada Border Services Agency

7.8 Other federal organizations had related responsibilities to support federal sustainable development strategy processes or the implementation of the selected target:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. The department is responsible for coordinating the development of the federal sustainable development strategy, for developing and maintaining systems and procedures to monitor progress on implementation of the strategy, and for preparing progress reports on the strategy at least once every 3 years.

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The secretariat plays a role across government in advancing the Greening Government goal of the federal sustainable development strategy. The secretariat is responsible for developing and supporting the rules of implementation related to greening government, for providing leadership and support to federal organizations, and for reporting on the target.

- Natural Resources Canada. The department offers services to federal organizations, including technical support for planning and deploying zero‑emission vehicles and charging infrastructure in government facilities. In doing so, the department provides analysis of vehicle operations (telematics) and advice for developing departmental fleet sustainability strategies.

- Public Services and Procurement Canada. The department is the government’s central purchaser. It establishes procurement tools for the purchase of vehicles for use by federal departments and agencies. This includes providing tools to make zero‑emission and conventional hybrid vehicles available for purchase to meet government organizations’ needs and placing orders once requirements are identified. The department maintains government‑wide data on all vehicles’ purchase orders, including those placed for zero‑emission vehicles.

7.9 In 2015, Canada committed to achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) calls for signatories to do the following: “Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities.” The government’s commitment to replacing its vehicle fleet with zero‑emission vehicles relates directly to this goal and to Goal 13 (Climate Action). All federal ministers and organizations are accountable for implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals within their areas of responsibility.

Focus of the audit

7.10 This audit focused on whether selected federal organizations contributed to meeting the target of zero‑emission vehicles in the federal administrative fleet under the Greening Government goal in the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. The audit also focused on whether they demonstrated their contributions to target 12.7 (to promote sustainable public procurement practices) under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as applicable to each organization.

7.11 This audit is important because increasing the proportion of zero‑emission vehicles in the federal administrative fleet not only contributes to the government’s broader goal of reducing emissions, but also demonstrates leadership in fighting climate change. By developing and reporting on departmental sustainable development strategies, federal organizations can demonstrate this leadership and highlight what steps must still be taken in their actions to achieve lower emissions.

7.12 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Despite some contributions, the government is unlikely to meet its target of 80% of vehicles in the federal administrative fleet being zero‑emission vehicles by 2030

7.13 This finding matters because replacing conventional internal combustion engine vehicles with zero‑emission vehicles will contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

7.14 The government has committed to achieving net‑zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. As part of the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy and the Greening Government Strategy, the government stated that it would lead by example by greening government operations. This included replacing its vehicle fleet with zero‑emission vehicles.

7.15 One of the long‑term goals of the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy is as follows: “The Government of Canada will transition to low‑carbon, climate-resilient, and green operations.” Under this goal, the government has a medium‑term target as follows: “Our administrative fleet will be comprised of at least 80% zero‑emission vehicles by 2030.” For that target, the government has 3 short‑term milestones:

- “75% of new light‑duty unmodified administrative fleet vehicle purchases will be zero‑emission vehicles or hybrids.”

- “All new executive vehicle purchases will be zero‑emission vehicles or hybrids.”

- “Departments will develop a strategic approach and take actions to decarbonize their fleets (including on‑road, air, and marine).”

7.16 The contributing actions for the target are the following:

- “Fleet management will be optimized including by applying telematics to collect and analyze vehicle usage data on vehicles scheduled to be replaced.”

- “The potential use of alternative energy options in national safety and security-related fleet operations will be examined.”

7.17 The 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy states that the performance indicator used to measure success is the percentage of vehicles in the federal administrative fleet that are zero‑emission vehicles. The Centre for Greening Government, in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, reports progress against this indicator yearly.

7.18 According to the secretariat’s guidance, light‑duty vehicles are typically replaced every 7 years. Consequently, the secretariat noted that for the government to achieve the 2030 target, starting no later than in the 2024–25 fiscal year, at least 80% of new purchases will have to be zero‑emission vehicles (assuming a 7‑year ownership cycle).

7.19 In their 2020–2023 departmental sustainable development strategies, federal organizations were expected to describe the actions that they would take in support of the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy’s goals, targets, and contributing actions. They were also expected to outline how they would measure their departmental actions and show results. The secretariat required federal organizations that had 50 or more vehicles to report annually on the composition of their administrative fleets. However, federal organizations that had fewer vehicles or that were not bound by the Federal Sustainable Development Act could also report voluntarily. In 2022, 24 federal organizations reported to the secretariat on the compositions of their fleets (Exhibit 7.3).

Exhibit 7.3—As of 31 March 2022, most vehicles in the largest federal administrative fleets were powered by internal combustion engines

| Federal organization | Internal combustion vehicles | Conventional hybrid vehicles | Zero‑emission vehicles | Administrative fleet total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Defence | 5,834 | 406 | 225 | 6,465 |

| Parks Canada | 1,576 | 44 | 45 | 1,665 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 1,243 | 63 | 31 | 1,337 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 998 | 103 | 12 | 1,113 |

| Remaining organizations | 5,756 | 651 | 273 | 6,680 |

| Government of Canada totalNote * | 15,407 | 1,267 | 586 | 17,260 |

Source: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Lack of a comprehensive strategic approach to incorporate zero‑emission vehicles into fleets

7.20 We found that none of the selected federal organizations with the largest fleets had developed a comprehensive strategic approach to decarbonizing their fleets (one of the short‑term milestones):

- National Defence, the organization with the largest fleet, provided high‑level information on some activities it planned for greening its fleets; however, these descriptions did not provide details on implementation to meet the 80% target by 2030.

- Parks Canada reported that all of its business units had 5‑year fleet-replacement plans. Although there were replacement plans, they did not explain how the agency would meet the target of 80% of vehicles being zero‑emission vehicles by 2030.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada stated in its departmental strategy that it would use its Departmental Vehicle Acquisition Plan to determine the opportunities to acquire zero‑emission vehicles and the number of administrative vehicles to be replaced by zero‑emission vehicles to meet the 2030 target. However, the department did not report the results related to the use of the plan for acquiring zero‑emission vehicles. We also found that the plan was not being fully implemented, partly because of low market availability. Notably, available zero‑emission trucks did not meet the department’s operational requirements, which included trucks that could tow or carry heavy loads.

- The Canada Border Services Agency’s 2019 investment plan noted that higher‑than‑expected purchase costs of zero‑emission vehicles would affect the agency’s ability to meet the target. The agency reported that in the development of a further national fleet investment plan, it would be seeking additional funds for the purchase of zero‑emission vehicles to meet the 2030 target. The agency had deferred, to the 2025–26 fiscal year, the start of implementing its actions to meet the target of 80% of vehicles being zero‑emission vehicles.

7.21 One strategy to decarbonize a fleet would be to determine whether fewer vehicles are required for operations, as fewer vehicles could lead to lower emissions. Right‑sizing the fleet could also save on costs. According to an analysis prepared for Natural Resources Canada, vehicles in the administrative fleet are used, on average, for less than half the number of kilometres each year that the secretariat recommends. Although this data was collected during the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 2 pandemic when some operations were reduced, the secretariat noted that the analysis suggested that there were opportunities to right‑size the fleet and reduce the number of vehicles. We found that the federal organizations did not report on whether they had right‑sized their fleets to contribute to reaching the 80% target.

7.22 Telematics is a source of information that can support decisions about fleet right‑sizing. Telematics devices installed in fleet vehicles can capture data such as fuel consumption, kilometres travelled, idling times, and emissions. We found that in their departmental strategies, all 4 entities planned on optimizing fleet management by using telematics to collect and analyze data on the use of vehicles scheduled to be replaced:

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency reported the number of vehicles logging travel information through telematics, but they did not report on the results. Although Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not report on the results of telematics within its departmental sustainable development strategy reports, we found that the department used telematics data to analyze the fleet.

- The Canada Border Services Agency stated in its 2020–21 Fleet Acquisition Plan that it had deployed telematics units to support more informed decision making about its future fleet composition.

- Parks Canada reported that analyses of telematics reports pointed to the need for infrastructure to support electric vehicles and the need to conduct assessments of federal facilities’ potential to accommodate electric vehicle chargers. Through assessments conducted by Natural Resources Canada, Parks Canada reviewed 4 of its sites’ historical power consumption, electrical service capacity, and existing power distribution systems. Parks Canada officials told us that telematics information was useful for gaining organizational support for adding zero‑emission vehicles to the agency’s administrative fleet.

- Although National Defence did not report on telematics, it conducted 2 trials but determined that it would use data from its own tracking system to inform purchase decisions.

7.23 One of the 3 short‑term milestones to obtaining 80% zero‑emission vehicles by 2030 is that 75% of new light‑duty unmodified administrative fleet vehicle purchases must be zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles. Conventional hybrid vehicles, in contrast to plug‑in hybrid electric vehicles, are not included in the zero‑emission vehicle definition (Exhibit 7.2), yet they contribute to progress toward the short‑term milestone. This means that a department or agency could reach the milestone by acquiring conventional hybrid vehicles without making any progress toward the 2030 target. In our opinion, focusing primarily on the milestone without having a strategy for decarbonizing the fleet to increase zero‑emission vehicles (paragraph 7.20) is not strategic, as acquiring conventional hybrid vehicles instead of zero‑emission vehicles will not lead to meeting the target or contribute to the same reduction of emissions.

7.24 We also noted that the 2022–2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy had increased the desired percentage of zero‑emission vehicles in the fleet by 2030 from 80% to 100%. This increase adds to the urgency of developing and implementing strong strategic approaches for acquiring zero‑emission vehicles.

7.25 National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency should develop strategic approaches to decarbonizing their fleets and expedite their implementation. These approaches should leverage the potential of telematics information to adapt fleet size and composition to meet operational needs and reduce emissions.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Despite some contributions, unlikely meeting of target

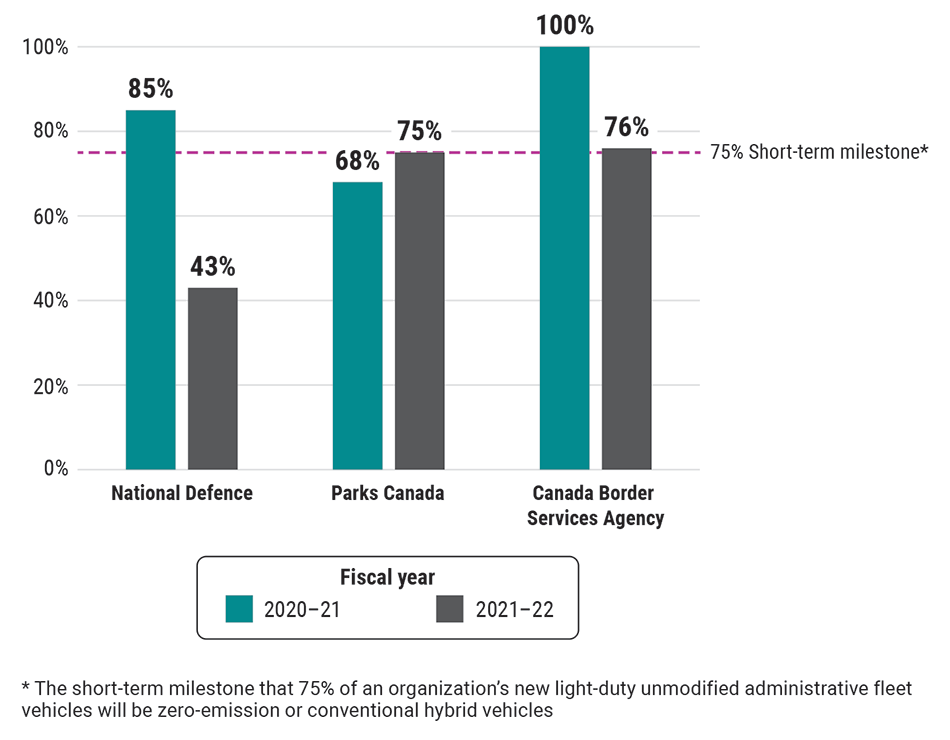

7.26 We found that some of the selected organizations fell short of the short‑term milestone for percentages of vehicle purchases that were conventional hybrid or zero‑emission vehicles in the administrative fleets, according to their own reports (Exhibit 7.4). Only the Canada Border Services Agency reported having met the short‑term milestone in both of the years under audit.

Exhibit 7.4—Some percentages of vehicle purchases that were zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles did not meet the short‑term milestone of 75%

Note: Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not report on the percentage of its vehicle purchases that were zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles.

Source: Departmental sustainable development strategy reports

Exhibit 7.4—text version

This bar chart shows the percentages of vehicle purchases that were zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles at National Defence, Parks Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency in the 2020–21 and 2021–22 fiscal years. Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not report on the percentage of its vehicle purchases that were zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles.

Only the Canada Border Services Agency met the short-term milestone of 75% in both years—that is, that 75% of an organization’s new light‑duty unmodified administrative fleet vehicles will be zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles. In 2020–21, 100% of the agency’s vehicle purchases were zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles, while in 2021–22, 76% were.

National Defence met the short-term milestone of 75% in 2020–21 but did not meet it in 2021–22. In 2020–21, 85% of the department’s vehicle purchases were zero-emission or conventional hybrid vehicles, while in 2021–22, 43% were.

Parks Canada did not meet the short-term milestone of 75% in 2020–21 but did meet it in 2021–22. In 2020–21, 68% of the agency’s vehicle purchases were zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles, while in 2021–22, 75% were.

7.27 For the whole of government, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat noted that as of 31 March 2022, of the total 17,260 vehicles in the administrative fleet, 586 were zero‑emission vehicles (3%) and 1,267 were conventional hybrid vehicles (7%).

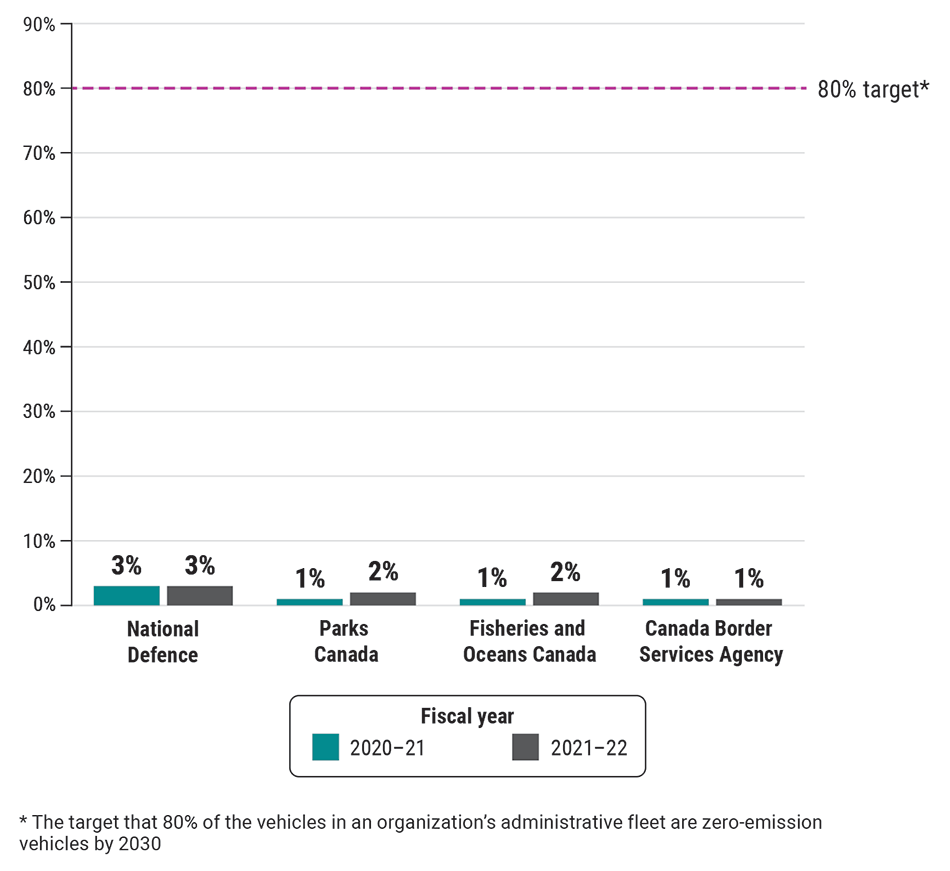

7.28 We used data from the selected entities to determine the percentages of zero‑emission vehicles. We found that the percentages of zero‑emission vehicles in the administrative fleets of the 4 selected federal organizations were well below the target of 80% (Exhibit 7.5). We noted that any purchases of zero‑emission vehicles contributed, albeit marginally, to the target.

Exhibit 7.5—Percentages of zero‑emission vehicles in federal administrative fleets were well below the government’s 2030 target of 80%

Source: Data from the selected federal organizations

Exhibit 7.5—text version

This bar chart shows the percentages of zero-emission vehicles in the administrative fleets of National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency in the 2020–21 and 2021–22 fiscal years. The percentages for the 4 fleets ranged from only 1% to 3%, which were well below the target that 80% of the vehicles in an organization’s administrative fleet are zero‑emission vehicles by 2030.

At National Defence, 3% of vehicles in its fleet were zero‑emission vehicles in both 2020–21 and 2021–22.

At Parks Canada, 1% of vehicles in its fleet were zero‑emission vehicles in 2020–21, while 2% were in 2021–22.

At Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 1% of vehicles in its fleet were zero‑emission vehicles in 2020–21, while 2% were in 2021–22.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, 1% of vehicles in its fleet were zero‑emission vehicles in both 2020–21 and 2021–22.

7.29 Several factors have limited the selected organizations’ ability to meet the 80% target. These include the lack of a strong strategic approach by the federal organizations (see paragraphs 7.20 to 7.24), as well as external barriers, which officials of these organizations described to us:

- Availability. Zero‑emission vehicles are not always available for purchase and cannot always be delivered quickly afterward to meet immediate needs. This was further compounded by the global supply issues created by the COVID‑19 pandemic.

- Specific types of zero‑emission vehicles. Not all of the operational requirements of the 4 selected federal organizations could be met by the zero‑emission vehicles on the market during the audit period. These included trucks needed to pull loads for long periods of time, vehicles to perform surveillance that should blend into surroundings, and vehicles that can work in harsh weather conditions.

- Infrastructure. Some federal organizations use vehicles in rural and remote regions far from departmental buildings and far from charging and hydrogen stations. The distance between sites and charging stations could lead to employees getting stranded or wasting time trying to find charging stations. Our audit on the Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Program found that many areas of the country still had limited access to public charging stations.

Reducing these barriers would help organizations contribute to meeting the 80% target.

7.30 Furthermore, a March 2023 expert report prepared for Natural Resources Canada concluded that achieving the target could be affected by uncertainties about zero‑emission vehicle availability for certain vehicle types (such as 3/4‑tonne and 1‑tonne pickup trucks) and that ineffective fleet planning could lead to large costs. The report also stated that the predicted volume of zero‑emission vehicles on the market could allow organizations to purchase many vehicles by 2030, but not necessarily the types that would be operationally required (for example, there may be limited volume for select segments like 3/4‑tonne and 1‑tonne pickup trucks).

7.31 In our opinion, the 80% target is unlikely to be met. Given the average progress made over the past 2 years by the selected organizations and the 8 years left for the government to reach the target, if the federal organizations continue with the same level of progress, we conservatively estimate that only 13% of the government’s administrative fleet will be zero‑emission vehicles by 2030.

Weaknesses in reporting on progress

7.32 We found weaknesses in the selected federal organizations’ reporting on progress in their departmental sustainable development strategy reports.

7.33 As required by the federal sustainable development strategy, each of these organizations prepared a departmental sustainable development strategy that followed key elements of the guidance from Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. We found that these departmental strategies showed the organizations’ planned contributions toward meeting the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy’s target of 80% of vehicles being zero‑emission vehicles in the federal administrative fleet by 2030. However, the strategies and reported results focused mostly on the short‑term milestone of having 75% of new light‑duty unmodified administrative fleet vehicle purchases being zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles.

7.34 The 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy states that the performance indicator used to measure success is the percentage of the federal administrative fleet comprising zero‑emission vehicles, contributing to the 80% target:

- Only the Canada Border Services Agency identified this performance indicator in its departmental sustainable development strategy. The agency reported that 2% of the administrative fleet were zero‑emission vehicles in 2020–21 and 1% in 2021–22.

- Although it had not included it as an indicator, Parks Canada reported that 5% of its administrative fleet were zero‑emission vehicles by 31 March 2021 and 3% were light‑duty fleet vehicles in 2021–22.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada included a total number for all conventional hybrid, plug‑in hybrid, and zero‑emission vehicles purchased in each year but did not report percentages. Furthermore, in 2020–21, the department made a mistake in reporting 69 vehicles. Officials told us the number reported should have been 19.

- National Defence did not include this performance indicator in its departmental sustainable development strategy or report on it in its reports on the strategy.

We noted that there were inconsistencies between the reported percentage results, as given in the Canada Border Services Agency’s and Parks Canada’s departmental sustainable development strategy reports, and the data the federal organizations provided to us (Exhibit 7.5). However, it remains that the 80% target is unlikely to be met whether one relies on our calculations or the reported results from the organization’s own reports.

7.35 In their departmental sustainable development strategy reports, 3 of the 4 selected organizations (all but National Defence) included commitments that new purchases of vehicles to be used by federal executives would be zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles, which was 1 of the 3 short‑term milestones. Only the Canada Border Services Agency reported results, stating that it had not purchased zero‑emission or conventional hybrid executive vehicles. There was no need to purchase executive vehicles during that period at the agency.

7.36 National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency should report in their departmental sustainable development strategy reports the numbers and percentages of zero‑emission vehicles (including battery electric, plug‑in hybrid electric, and hydrogen fuel cell electric) and conventional hybrid vehicles in their administrative fleets separately, in addition to the yearly procurement totals of these types of vehicles. Such reporting would better demonstrate their progress toward the target of 80% of vehicles being zero‑emission vehicles and the short‑term milestone of 75% of their vehicle purchases being zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Selected federal organizations had limited reporting on how their results related to zero‑emission vehicles contributed to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 12

7.37 This finding matters because implementing the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will require efforts from across Canadian society, including all of government. The federal government therefore expects federal organizations to contribute to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals within their areas of responsibility. As this relates to Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), the federal government can lead by acquiring zero‑emission vehicles.

7.38 In September 2015, Canada adopted the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

7.39 The government’s target that the “administrative fleet will be comprised of at least 80% zero‑emission vehicles by 2030” falls within the Greening Government federal goal in the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. It also relates to Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and more specifically to target 12.7: “Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities.”

7.40 The government’s guidance for preparing departmental sustainable development strategies and reports suggests that federal organizations identify which (if any) of the Sustainable Development Goals and targets their actions relate to. Every year, most federal organizations must produce a departmental results report, which, the guidance also suggests, should include links to the Sustainable Development Goals. This report is an account of actual results for the most recently completed fiscal year against the plans, priorities, and planned results set out in departmental plans.

Limited reporting when linking departmental actions and Goal 12

7.41 We found that in their departmental strategies and reports, the 4 selected organizations with the largest fleets followed guidance from Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and linked their departmental actions to Goal 12, with 2 organizations also specifying target 12.7 (“Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities”).

7.42 However, the 4 selected organizations with the largest fleets did not describe how the results achieved by their policies, programs, initiatives, and investments advanced the achievement of Goal 12 in their departmental results reports, in accordance with Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat guidance.

7.43 We also found that the 4 federal organizations with supportive roles provided guidance to the 4 with the largest administrative fleets. This included various strategies, policies, directives, and practices aimed at supporting the acquisition of zero‑emission vehicles. In turn, these would contribute toward achieving Goal 12 and target 12.7. Although this guidance did not specifically suggest that federal organizations report on their supporting actions, we found some reporting on the supporting actions in these organizations’ departmental strategies and reports:

- Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat linked to target 12.7 in their departmental strategies and reports.

- Natural Resources Canada included its supportive actions and linked them to Goal 13 (Climate Action).

7.44 In their departmental results reports, although it was not required, Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat linked some of their supporting actions to Goal 12 and target 12.7. Doing so provided information on the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal.

Conclusion

7.45 We concluded that National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency contributed marginally to meeting the target of 80% of vehicles in the federal administrative fleet being zero‑emission vehicles by 2030. In these efforts, they were supported by Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Natural Resources Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada. However, the pace and the extent of the contributions make meeting the target unlikely by 2030.

7.46 Moreover, the selected organizations’ reporting on how their results related to zero‑emission vehicles contributed to progress toward the achievement of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and target 12.7 (“Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities”) was limited.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the contribution of departmental sustainable development strategies to the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the implementation of selected federal entities’ departmental sustainable development strategies complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the selected federal entities contributed to meeting the target of zero‑emission vehicles in the federal administrative fleet under the Greening Government goal in the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy and related to target 12.7 (to promote public procurement practices that are sustainable) under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as applicable to each entity.

Scope and approach

We selected the following target from the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy to audit: that the “administrative fleet will be comprised of at least 80% zero‑emission vehicles by 2030.” We audited the 4 entities that had the largest number of vehicles in their administrative fleets and that were required to report against the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy targets: National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency. We also included in the audit scope 4 entities that had related responsibilities: Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Natural Resources Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada.

We audited whether the 4 entities with the largest number of vehicles had complied with key expectations set out in guidance to establish their departmental sustainable development strategies and whether the actions included in those strategies would, over time, contribute to the target. We reviewed the 4 entities’ 2020–21 and 2021–22 progress reports on their departmental sustainable development strategies to determine whether the strategies had complied with key expectations from guidance and whether the entities had implemented their plans and achieved their objectives related to the specific target.

For the entities that played related supportive roles, we examined their key actions, such as providing guidance.

For all of the 8 entities within the audit scope, we examined whether they reported how their results contributed to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), with a focus on target 12.7 (“Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities”).

We gathered audit evidence through document reviews, interviews with federal officials, and data analyses. This included testing a sample of data from the selected organizations. We found issues related to data accuracy and completeness. This means that we could not confirm the accuracy of the data used in this report and what the organizations reported in their departmental sustainable development strategy reports. Notwithstanding the data quality issues, our findings related to the unlikely meeting of the target and the audit conclusion are unaffected.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Organizations prepare departmental sustainable development strategies that contribute to meeting the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy’s target on zero‑emission vehicles in the federal administrative fleet in the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. |

|

|

Organizations implement the plans and report the extent to which they meet the objectives related to the target on zero‑emission vehicles in the federal administrative fleet or related to their supporting roles set out in their departmental sustainable development strategies. |

|

|

Organizations report how the results achieved by their policies, programs, initiatives, or investments related to the composition of the government’s administrative fleet contributed to advancing target 12.7 (to promote public procurement practices that are sustainable) under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as identified in their departmental sustainable development strategies. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 June 2020 to 31 March 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 2 November 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Susan Gomez, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

7.25 National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency should develop strategic approaches to decarbonizing their fleets and expedite their implementation. These approaches should leverage the potential of telematics information to adapt fleet size and composition to meet operational needs and reduce emissions. |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence will develop its strategic approach through the department’s Defence Energy and Environment Strategy outlining the department’s commitment to implement Government of Canada obligations. National Defence will expedite efforts and implementation of fleet rationalization where operationally viable. Telematics continue to be analyzed and tested; however, current fleet management data collection methods provide greater fidelity and accuracy to gather the necessary information to meet the goals outlined in the strategy. Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada is currently developing the Net‑Zero Carbon Portfolio Plan, which includes elements to expedite fleet decarbonization. The plan will identify the resources and strategies, including adapting fleet size and composition, required to meet operational needs and reduce emissions. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canadian Coast Guard’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will ensure that it expedites the implementation of its existing vehicle rationalization strategy in order to meet the 80% target by 2030. The department is committed to using telematics data to inform its plan so that the plan clearly identifies specific fleet vehicles that are the most suitable for replacement by existing zero‑emission vehicle models. Implementation date: December 2023 The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. Over the past several years, the Canada Border Services Agency has increased the amount of green vehicle purchases, and 2023–2024 represents the first year that the agency procured more green vehicles than traditional internal combustion engine vehicles. The agency continues to work with law enforcement partners to develop a decarbonization plan by March 2025 that will assist it in achieving the greening targets set out by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Additionally, the agency is currently undertaking a strategic fleet review and is considering options on how to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. These options include leveraging existing telematics and reducing the size of the fleet. |

|

7.36 National Defence, Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency should report in their departmental sustainable development strategy reports the numbers and percentages of zero‑emission vehicles (including battery electric, plug‑in hybrid electric, and hydrogen fuel cell electric) and conventional hybrid vehicles in their administrative fleets separately, in addition to the yearly procurement totals of these types of vehicles. Such reporting would better demonstrate their progress toward the target of 80% of vehicles being zero‑emission vehicles and the short‑term milestone of 75% of their vehicle purchases being zero‑emission or conventional hybrid vehicles. |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence will report vehicle types and inventories to Parliament in annual Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy progress reports. National Defence will also continue to engage with partners and central agencies to achieve better alignment and sequencing of Federal Sustainable Development Strategy performance reporting. Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada is committed to working with Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Centre for Greening Government to improve reporting information that better demonstrates progress toward the targeted percentage of zero‑emission vehicles. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canadian Coast Guard’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will ensure that its reporting is thorough and differentiates zero‑emission, conventional hybrid electric, and plug‑in hybrid electric vehicles to more clearly identify the department’s progress toward the targets and milestones. Implementation date: November 2023 The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, the Canada Border Services Agency will report the numbers and percentages of zero‑emission, conventional hybrid electric, and plug‑in hybrid electric vehicles in their administrative fleets separately. Fleet Management will work with Environmental Operations to ensure the information is reported separately in the Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy annual progress reports by September 2024. |

Appendix—Organizations Subject to the Federal Sustainable Development Act

On 1 December 2020, amendments to the Federal Sustainable Development Act came into force. These amendments significantly expanded the number of federal organizations that must contribute to developing the 2022–2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, including related documents, and report on their contributions through their own departmental sustainable development strategies, among other obligations. As of 1 December 2020, there were 100 organizations subject to the act.

The addition of these organizations to the schedule of the Federal Sustainable Development Act widened the scope of the act’s application and will promote greater coordination of actions related to sustainable development across the federal government.

Under the previous Federal Sustainable Development Act, there were 27 organizations that contributed to the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. Collectively, these organizations have developed a total of 648 actions under their 2020–2023 sustainable development strategies that contributed to the federal strategy’s 13 goals, as illustrated in the table below.

Note: The numbers below represent the number of actions per organization and per goal.

| Designated organizations listed in the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy | Effective action on climate | Greening government | Clean growth | Modern and resilient infrastructure | Clean energy | Healthy coasts and oceans | Pristine lakes and rivers | Sustainably managed lands and forests | Healthy wildlife populations | Clean drinking water | Sustainable food | Connecting Canadians with nature | Safe and healthy communities | Number of actions contributing to the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy per organization | Number of goals contributed to the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy per organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada | 5 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 3 |

| Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 24 | 4 |

| Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 1 |

| Canadian Heritage | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| Department of Justice Canada | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 23 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 17 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 19 | 102 | 10 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 41 | 7 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 2 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 3 |

| Health Canada | 3 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 32 | 5 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 4 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 29 | 5 |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 4 | 14 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 30 | 7 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 6 | 21 | 21 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 4 |

| National Defence | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16 | 3 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 41 | 9 |

| Parks Canada | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 30 | 8 |

| Prairies Economic Development Canada | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 3 |

| Public Safety Canada | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 3 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 3 |

| Transport Canada | 11 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 43 | 5 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Veterans Affairs Canada | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 |

| Number of departmental actions per federal goal | 78 | 324 | 38 | 9 | 15 | 32 | 23 | 11 | 21 | 4 | 24 | 7 | 62 | 648 | 0 |

| Number of organizations contributing to each federal goal | 14 | 27 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |