2024 Reports 1 to 5 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 1—Contaminated Sites in the North

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Canada’s financial liability to remediate contaminated sites had increased significantly since 2005

- Targets for environmental and human health risks were mostly unmet in Canada, but contaminated sites in the North managed according to requirements

- There was a lack of meaningful information and performance measurement for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan

- Large abandoned mines in the North pose significant costs and environmental risks for current and future generations

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 1.1—Federally managed contaminated sites in northern Canada

- 1.2—Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan funding and priorities over time

- 1.3—Canada’s financial liability for contaminated sites had increased since 2005, notwithstanding progress made in closing sites

- 1.4—Delays in the Rayrock uranium mine project resulted in millions of dollars in deferred spending

- 1.5—The Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s targets to reduce environmental and human health risks were not all achieved for phase 3 (2016–17 to 2019–20) and were not on track to all be met for phase 4 (2020–21 to 2024–25)

- 1.6—The Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan annual targets related to climate change were unmet

- 1.7—Giant Mine costs rose significantly, and remediation work was not expected to be completed until 3 decades after it was abandoned

- 1.8—Faro Mine costs increased significantly, though the remediation phase had not yet started

Introduction

Background

1.1 Contaminated sites are locations—such as abandoned mines, airports, industrial facilities, landfills, and military bases—that contain substances that could harm the environment and human health. If not managed properly, they can pollute surrounding water, soil, and air. They also take valuable land out of productive use and can jeopardize the way of life of those who live off the land.

1.2 The federal government is responsible for managing certain types of contaminated sites, including ones that it owns and others for which it has accepted financial responsibility. Canada has a public inventory that lists federally managed sites that are suspected to be contaminated, are active, or have been closed.

1.3 As of March 2023, there were 24,109 contaminated sites across Canada, including 2,627 in the North—defined as being above the 60th parallel for the purposes of this audit. The federal government has closed 18,110 sites, including 8,639 where no action was required. Site closures indicate that the financial liabilityDefinition 1 has been reduced to zero and that no further action is required. These closed sites demonstrate the progress made toward reducing the outstanding risks to the environment and human health and the associated liability.

1.4 The remaining contaminated sites represent a significant cost for Canadians. As of March 2023, 4,503 active sites in Canada had not yet been remediated, including 322 in the North, and 1,496 suspected contaminated sites that had not yet been assessed, including 107 sites in the North. For the unassessed federal sites, and many active sites not yet in the remediation phase, the liability could increase until the full extent of the estimated costs to remediate or to risk manage its sites is known.

1.5 In March 2023, the Government of Canada estimated the total financial liability of federal contaminated sites at $10.1 billion. While only 11% of the federal sites are in the North, they represent more than 60% of the total liability.

1.6 This audit examined 2 programs that share the common objective of reducing environmental and human health risks at contaminated sites and the associated financial liabilities:

- Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. This cost‑shared program involves 19 federal departments, agencies, and Crown corporations—17 of which are responsible for managing contaminated sites and are known as custodians. The program aims to help them address the contaminated sites that they are responsible for.

- Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. Announced in Budget 2019, this program, administered by Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, includes the 8 largest and highest‑risk abandoned mine projects in Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

1.7 We focused on Environment and Climate Change Canada and the support the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat provided in their roles as administrators of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. In addition, we examined 2 custodians, Transport Canada and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, both of which manage contaminated sites in the North. Together, these 2 departments oversee almost 50% of the active, suspected, and closed contaminated sites in that region (Exhibit 1.1).

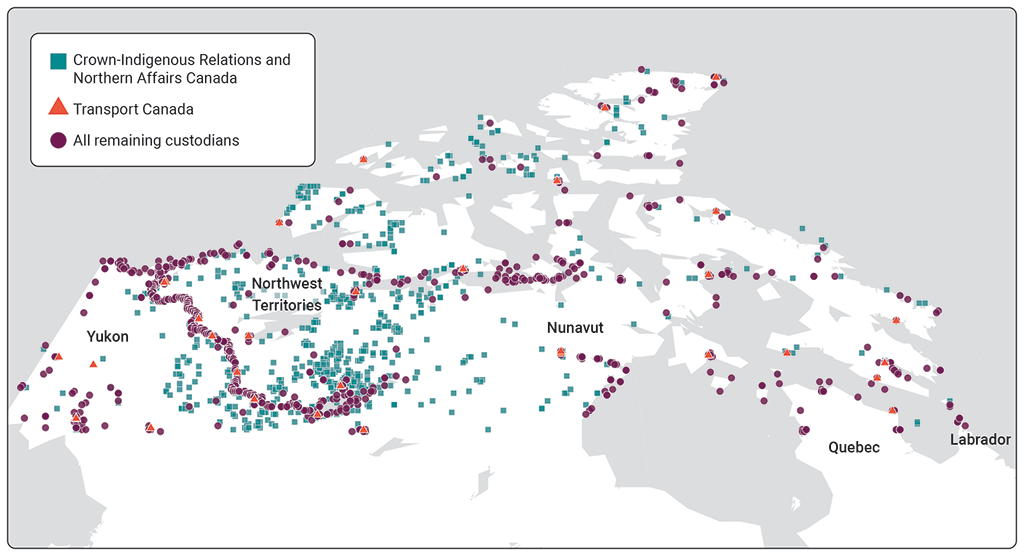

Exhibit 1.1—Federally managed contaminated sites in northern Canada

Note: The map includes all federal contaminated sites in the North, including active, closed, and suspected sites. The map is not proportional.

Source: Adapted from data provided by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Exhibit 1.1—text version

This map includes all federal contaminated sites in the North, including active, closed, and suspected sites. It indicates the sites that are managed by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, by Transport Canada, and by all other custodians. In total, there are 2,567 sites.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada manages 1,003 contaminated sites in North. Although they are spread out across the 3 territories, most of these sites are located in the Northwest Territories and in the western part of Nunavut.

Transport Canada manages 131 sites, which are spread out across the North.

The remaining 1,433 sites, which are managed by all remaining custodians, are also spread out across the North, with most in Nunavut and in the Northwest Territories. Many of them are close to the water, such as along the northern coast.

1.8 Environment and Climate Change Canada. This department administers the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan with support from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. It provides guidance and leadership to custodians, coordinates data management activities, tracks funding requests and transfers, and tracks project expenditures.

1.9 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. This central agency advises on Treasury Board policy matters and administers and maintains the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory, a database of both known and suspected contaminated sites. It supports the work of Environment and Climate Change Canada by advising on the strategic aspects of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and the monitoring of government‑wide progress in addressing federal contaminated sites funded under the program.

1.10 Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. This department identifies, assesses, manages, remediates, and closes the contaminated sites under its responsibility. As of March 2023, it was managing 150 active federal contaminated sites in the North. It manages its portfolio of contaminated sites through the Northern Contaminated Sites Program, which includes sites funded by the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan, the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program, and departmental funding.

1.11 Transport Canada. This department administers the federal contaminated sites under its responsibility. It identifies, assesses, manages, remediates, and closes contaminated sites under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. As of March 2023, it was overseeing 38 active federal contaminated sites in the North.

1.12 The Office of the Auditor General of Canada first audited federal activities involving federal contaminated sites in 1995. The 2002 report on federal contaminated sites by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development outlined the federal government’s obligation to locate, assess, and remediate these sites and led to the establishment of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan in 2005. Our office has since conducted other audits in addition to the financial audit work on contaminated sites, including abandoned mines, and found gaps in site management.

Focus of the audit

1.13 This audit focused on whether Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Transport Canada, working with Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, effectively managed federal contaminated sites in the North by reducing the risks to the environment and human health and the associated financial liability for current and future generations. The programs we examined included the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. Regarding the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan, where information was not available for the North or appropriate to look at in isolation, we examined the Canada‑wide program measurement, reporting, and results.

1.14 This audit is important because exposure to hazardous substances has been linked to adverse health conditions for humans. Left unaddressed, the environmental and human health risks, and the associated liabilities, could increase if contaminants move, especially if they spread beyond federal property boundaries.

1.15 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Canada’s financial liability to remediate contaminated sites had increased significantly since 2005

1.16 This finding matters because the costs to remediate federal contaminated sites are a burden to current and future generations of Canadian taxpayers. In addition, proper cost estimates for addressing federal contaminated sites help the government make decisions to reduce environmental risks and address contaminated sites in a cost‑effective manner.

1.17 Canada established the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan in 2005 as a 15‑year program, divided into 3 phases with funding of $4.5 billion. At the time, the financial liability for known federal contaminated sites was $2.9 billion and the objective of the program was to reduce the financial liability for eligible sites by 2020. In 2019, the government renewed the program for 15 more years (with 3 additional phases) and provided $1.2 billion in funding for the first 5 years. The plan encompasses sites across Canada, including in the North (Exhibit 1.2).

Exhibit 1.2—Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan funding and priorities over time

| Phase | Time frame (fiscal year) | Funding | Objectives and priorities |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Phases 1 to 3 |

2005–06 to 2019–20

|

$4.5 billionNote *

|

Objectives

|

|

Phase 4 |

2020–21 to 2024–25 |

$1.2 billion |

In addition to the above objectives, in phase 4, the program had the following priorities:

|

|

Phases 5 and 6 |

2025–26 to 2034–35 |

Not announced by the end of our audit period |

Not announced by the end of our audit period |

Source: Adapted from data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Unlikely to meet the program’s liability reduction target

1.18 We found that the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan did not meet its liability reduction target in phase 3. The program achieved 31% of the target ($177 million net reduction out of $574 million). Similarly, we found that the program was not on track to meet its liability reduction target by the end of phase 4. Rather, liability had increased by $9 million since the phase began. Environment and Climate Change Canada and its program partnersDefinition 2 did not expect to achieve the liability reduction target. They identified several reasons for this, including

- cost adjustments

- the pace of remediation progress

- variations in the comprehensiveness of assessment data

- limitations in cost estimates

- poor results from past phases

- the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19) pandemic and the associated supply chain effects

1.19 While significant progress had been made in closing sites since 2005, we found that the total financial liability for federal contaminated sites had increased and exceeded $10.1 billion in 2022–23 (Exhibit 1.3). Sites in the North make up over $6 billion of this total. By assessing contaminated sites, the federal government is able to develop a more accurate estimate of the liability it faces. Liability estimates often increase as more information becomes available and as the remediation plans are developed.

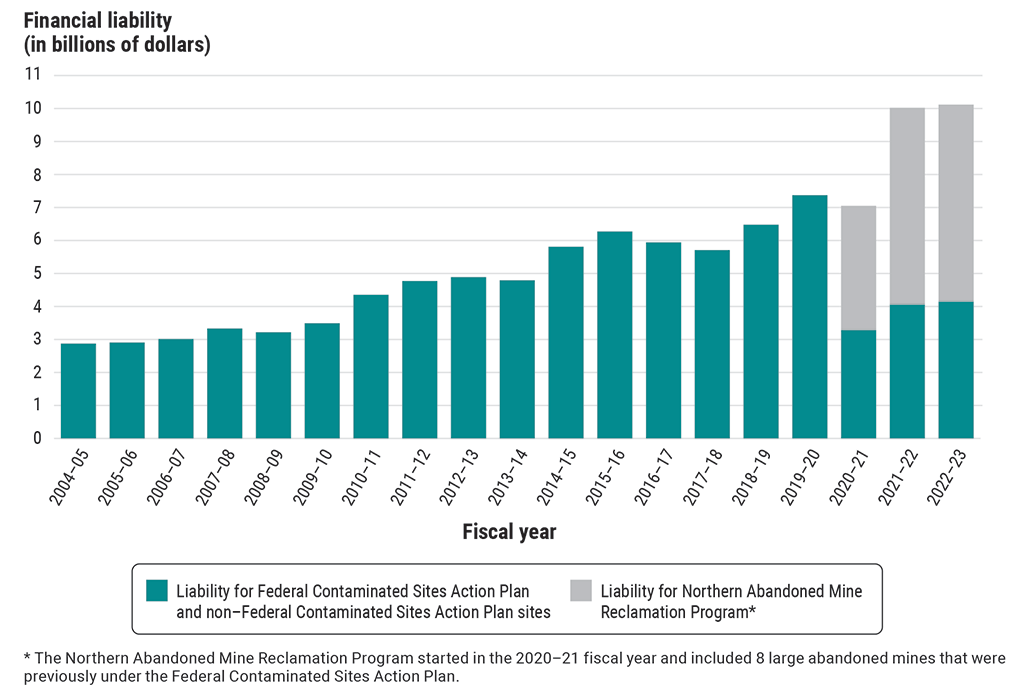

Exhibit 1.3—Canada’s financial liability for contaminated sites had increased since 2005, notwithstanding progress made in closing sites

Source: Adapted from data reported by the Public Accounts of Canada

Exhibit 1.3 chart 1—text version

Adapted from data reported by the Public Accounts of Canada, the graph shows the financial liability for contaminated sites for each fiscal year. The liability steadily increased during the period.

In 2004–05, the liability for Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and non–Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan sites was $2.87 billion.

In 2005–06, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $2.91 billion.

In 2006–07, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.01 billion.

In 2007–08, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.33 billion.

In 2008–09, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.22 billion.

In 2009–10, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.49 billion.

In 2010–11, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.35 billion.

In 2011–12, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.77 billion.

In 2012–13, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.89 billion.

In 2013–14, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.80 billion.

In 2014–15, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $5.81 billion.

In 2015–16, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $6.27 billion.

In 2016–17, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $5.94 billion.

In 2017–18, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $5.71 billion.

In 2018–19, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $6.48 billion.

In 2019–20, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $7.38 billion.

In the 2020–21 fiscal year, the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program started and included 8 large abandoned mines that were previously under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. In 2020–21, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.28 billion and the liability for the program was $3.77 billion.

In 2021–22, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.06 billion and the liability for the program was $5.97 billion.

In 2022–23, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.15 billion and the liability for the program was $5.97 billion.

Source: Data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Note: The liability for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and non–Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan sites can include sites that may have conducted activities using non–Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan funding. This is due to the limitations of the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory with respect to categorizing sites by program (see paragraph 1.53).

Exhibit 1.3 chart 2—text version

Using data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada, the graph shows the number of contaminated sites for the 2004–05 to 2022–23 fiscal years, broken into the following categories: suspected contaminated sites, active contaminated sites, and closed sites. The number of closed sites increased during the period.

In 2004–05, there were 6,200 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,000 suspected contaminated sites, 4,200 active sites, and 0 closed sites.

In 2005–06, there were 11,090 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 4,609 suspected contaminated sites, 5,352 active sites, and 1,129 closed sites.

In 2006–07, there were 19,947 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 11,841 suspected contaminated sites, 6,476 active sites, and 1,630 closed sites.

In 2007–08, there were 20,616 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 11,510 suspected contaminated sites, 6,601 active sites, and 2,505 closed sites.

In 2008–09, there were 20,344 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 10,809 suspected contaminated sites, 5,710 active sites, and 3,825 closed sites.

In 2009–10, there were 19,598 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 7,434 suspected contaminated sites, 6,949 active sites, and 5,215 closed sites.

In 2010–11, there were 22,017 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 6,958 suspected contaminated sites, 7,399 active sites, and 7,660 closed sites.

In 2011–12, there were 22,254 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 4,929 suspected contaminated sites, 6,845 active sites, and 10,480 closed sites.

In 2012–13, there were 22,382 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 4,014 suspected contaminated sites, 6,568 active sites, and 11,800 closed sites.

In 2013–14, there were 22,591 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 3,020 suspected contaminated sites, 6,144 active sites, and 13,427 closed sites.

In 2014–15, there were 22,820 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,606 suspected contaminated sites, 5,785 active sites, and 14,429 closed sites.

In 2015–16, there were 23,074 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,353 suspected contaminated sites, 5,340 active sites, and 15,381 closed sites.

In 2016–17, there were 23,279 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,060 suspected contaminated sites, 5,239 active sites, and 15,980 closed sites.

In 2017–18, there were 23,490 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,987 suspected contaminated sites, 5,067 active sites, and 16,436 closed sites.

In 2018–19, there were 23,667 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,842 suspected contaminated sites, 4,980 active sites, and 16,845 closed sites.

In 2019–20, there were 23,714 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,795 suspected contaminated sites, 4,860 active sites, and 17,059 closed sites.

In 2020–21, there were 23,897 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,738 suspected contaminated sites, 4,967 active sites, and 17,192 closed sites.

In 2021–22, there were 23,965 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,552 suspected contaminated sites, 4,762 active sites, and 17,651 closed sites.

In 2022–23, there were 24,109 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,496 suspected contaminated sites, 4,503 active sites, and 18,110 closed sites.

1.20 Even though $2.5 billion was spent on remediation during our audit period, the total federal liability increased by 59% due to cost adjustments of $5.9 billion. We found that the most common reason for liability adjustments was custodians revising their initial cost estimates for remediation—for example, when new contamination is discovered after the initial assessment. Other reasons for adjustments included the development of remediation plans, delays in site remediation, the lack of assessment data, and inflation. While custodians annually report adjustments to the liability, the reasons for increases are not reported. Tracking the reasons for adjustments and providing greater support for custodians in developing their liability estimates could improve their reliability.

1.21 Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, was unable to address the long‑standing issue of unspent annual program funding despite trying a few different strategies, including funding transfers among custodians and overplanning. We found that on average, 23% of the annual available funding was not spent in the year allocated. In 2021–22, the department began tracking the reasons for carrying forward funding by site. However, there had not been any improvements in the use of annual funding to date. Unspent funding is generally because of project delays and can contribute to higher costs to remediate sites in future years due to inflation.

1.22 In 2022–23, the department identified that custodians working in the North received a lower proportion of assessment funding during phase 4 than they had in previous phases. Yet this phase was designed to advance Indigenous people’s participation in all aspects of contaminated sites work by expanding site eligibility to allow funding to be used at more sites that affect Indigenous people. The department also reported that lower funding levels made it difficult for custodians to capitalize on the expanded eligibility criteria.

1.23 Our recommendation for this section is at paragraph 1.26.

Cost adjustments were the most significant reason for increased liability in the North

1.24 We found that the cost adjustments made by custodians in the North had a more significant effect on the change in the liability than expenditures made to reduce the liability. Some examples during our audit period included the following:

- Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s liability for sites in the North (excluding the 8 large sites that are part of the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program) increased by 18%, to $341.4 million from $290.5 million. While expenditures and financial adjustments reduced the liability by 26% and 1% respectively, project cost adjustments increased the liability by 44%.

- Transport Canada succeeded in reducing its liability for its portfolio of program-eligible contaminated sites in the North by 57%, to $17.0 million from $39.2 million. Expenditures and project cost adjustments reduced the liability by 35% and 41% respectively, while financial adjustments increased it by 19%. Transport Canada told us that cost estimates used to generate the original liabilities are often conservative, particularly in the North, to account for costs related to working in remote locations.

1.25 We found that the cost adjustments were primarily due to updated estimates for remediation costs, additional or revised long‑term monitoring plans, and extensions in project schedules. Exhibit 1.4 illustrates an example of project delays that resulted in deferred spending.

Exhibit 1.4—Delays in the Rayrock uranium mine project resulted in millions of dollars in deferred spending

Site of the Rayrock uranium mine in the Northwest Territories

Photo: Hatfield Consulting limitedLtd.

Rayrock was a uranium mine in the Northwest Territories that operated in the 1950s. Radioactive tailings contaminated the surrounding area. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada told us that it had experienced many administrative and technical challenges, as this was its most complicated Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan project.

In the 1990s, the federal government covered the tailings and sealed all mine entries. At that time, there was no engagement strategy, so the Tłįchǫ community was not involved with the project. In contrast, when assessment work resumed in the 2010s, the work undertaken to identify contaminants and hazards at the site and surrounding areas considered traditional-knowledge studies.

As the custodian, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada encountered delays in the remediation of the Rayrock site—for example, because of uncertainties with the remedial options or because its water and land‑use applications were deemed incomplete. As a result, millions of dollars that could have been used toward other sites were deferred.

Due to the radioactive nature of the contaminants, the Rayrock site will likely require long‑term care and monitoring, much like complex sites funded under the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program, which provides long‑term continuity in funding and a tailored management approach that these complex sites require.

1.26 To achieve the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s objective of reducing the financial liability, Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should support custodians in reducing financial liability by

- increasing custodians’ capacity to develop more accurate liability estimates—for example, by establishing average estimation gaps for a variety of projects, sharing lessons learned, and providing additional training and access to experts

- developing measures and flexibility mechanisms to reduce the funding carried forward and the associated delays in the remediation of contaminated sites

- conducting an analysis to identify and recommend appropriate proportions of assessment and remediation funding

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Targets for environmental and human health risks were mostly unmet in Canada, but contaminated sites in the North managed according to requirements

1.27 This finding matters because meaningful engagement and socio-economic benefits supporting reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and the consideration of climate change are integral to assessing and addressing environmental and human health risks—which are significant for people who live near contaminated sites. Without effective leadership, the program’s objectives and priorities may not be achieved.

1.28 From its beginning, the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s core objectives have been to reduce the risks to the environment and human health as well as the associated financial liability. As part of its renewal in 2019, however, the program also focused on supporting other federal government priorities, such as reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and addressing climate change. As such, the program is now an element of the government’s broader focus on environmental justice and aims to contribute to reconciliation from socio-economic and environmental perspectives.

1.29 When custodians suspect that a site is contaminated, they conduct assessments to find out what kinds of contaminants might be present and what risks these may pose. The custodians then evaluate and rank the sites and decide what action to take, such as developing and implementing a remediation plan or risk management strategy. A contaminated site is considered closed once the risks to the environment and human health have been adequately managed and no action is required. Generally, remediation in the North takes longer than in the other parts of Canada because of challenges like remoteness, the complex regulatory regime, and harsher weather.

Mostly unmet targets for environmental and human health risks

1.30 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, did not directly measure the outcomes from risk reduction activities in the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan, even though measuring these outcomes is one of the program’s primary objectives. Instead, the department measured and tracked risk reduction through measures such as the transition of contaminated sites into long‑term monitoring and closure stages. Even so, we found that the program did not meet all its targets for environmental and human health risk reduction in phase 3 and was not on track to meet all phase 4 targets (Exhibit 1.5).

Exhibit 1.5—The Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s targets to reduce environmental and human health risks were not all achieved for phase 3 (2016–17 to 2019–20) and were not on track to all be met for phase 4 (2020–21 to 2024–25)

| Phase | Indicator | Target | Result | Target progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 3 | Number of sites conducting risk reduction activities | 974 sites | 1,104 sites | Check mark in a green circle Met the target |

| Phase 3 | Number of sites completing risk reduction activities | 548 sites | 232 sites | An X in a red circle Did not meet the target |

| Phase 3 | Percentage of medium- and high‑risk sites where risk reduction activities have been completed since the start of the program in 2005 | 34% | 27% | An X in a red circle Did not meet the target |

| Phase 3 | Number of sites closed | 416 sites | 359 sites | An X in a red circle Did not meet the target |

| Phase 3 | Percentage of medium- and high‑risk sites that have been closed since the start of the program in 2005 | 26% | 18% | An X in a red circle Did not meet the target |

| Phase 4 (ongoing) | Percentage of sites completing risk reduction activities | 65% | 34% | Exclamation point in a yellow circle Unlikely to meet the target |

| Phase 4 (ongoing) | Percentage of sites closed or in long‑term monitoring | 60% | 66% | Check mark in a green circle Met the target |

|

Legend—Target progress Check mark in a green circle Met the target Exclamation point in a yellow circle Unlikely to meet the target An X in a red circle Did not meet the target |

||||

Source: Adapted from Environment and Climate Change Canada data

1.31 Our recommendation for this section is at paragraph 1.41.

Effective management of active sites in the North

1.32 We found that Transport Canada and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada managed active sites according to the requirements of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan.

1.33 In our examination of a representative sample of medium- to high‑risk active contaminated sites, we found that the departments’ risk‑based planning and decision making were supported by appropriate information and analysis. The departments also monitored activities on their sites by conducting site visits, producing field reports, and tracking site performance.

1.34 In our examination of closed sites, we found that the 2 departments met the objectives of the program and reduced environmental and human health risks to acceptable levels for 10 of the 11 medium- to high‑risk sites that they closed during our audit period. For the site that did not meet the objectives, Transport Canada informed us that the department closed it due to the transfer of responsibilities to the property owner. The site was closed in the inventory without any risk assessment or remediation completed.

Different approaches to address program priorities in the North

1.35 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada provided custodians with guidance and reporting templates related to site closure, climate change, Indigenous engagement, and training. The department also established minimum expectations, allowing custodians to supplement and adapt or use internal guidance and practices. This mixed approach contributed to differences in how custodians responded to requirements and addressed priorities.

1.36 Some of these differences included the following:

- Transport Canada carried out site‑specific assessments for the effects of climate change, while Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada assessed the effects through remediation action plans.

- Transport Canada carried out Indigenous engagement only to comply with land and water licence requirements, whereas Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada often carried out Indigenous engagement beyond licence requirements and incorporated Indigenous engagement and socio-economic considerations into its procurement planning.

- For the 11 medium- to high‑risk sites that were closed during our audit period, Transport Canada followed the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s closure report template, while Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada used its own closure report template. The latter included more details on Indigenous engagement, social benefits to the community, and financial information. Although sites were closed in the system for both departments, most of the closure reports were not signed by the end of our audit period.

1.37 In our view, a more consistent approach would allow for the aggregation of results and better demonstrate program performance. According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, “Consistent procedures and proper documentation, and the transparency this represents, increase public confidence in the overall management of federal contaminated sites and at individual sites.”

1.38 We also found that Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada closed 5 sites in 2020, 5 to 9 years after completing the final closure report for each of those sites. For 1 of these sites, we found that the closure report was outdated, inaccurate, and unclear as to whether all the remediation objectives were achieved. In our view, these weaknesses could affect public trust and the achievement of the expected environmental and human health risk reduction.

1.39 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not carry out any quality checks to ensure that the site closures were carried out appropriately. While carrying out quality checks is not a requirement for the department, this is concerning because the department uses site closures to demonstrate the reduction of environmental and human health risks.

1.40 We also found that the 2022 climate change adaptation guidance that Environment and Climate Change Canada provided to custodians contained a framework for climate change adaptation, but it did not address mitigation or describe how custodians should consider the effects of climate change. The limited guidance on mitigation could lead custodians to favour transporting contaminants off‑site, which can produce greenhouse gas emissions.

1.41 To achieve the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s objective of reducing the environmental and human health risks, and to support custodians more effectively and make greater progress toward program priorities—such as reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and climate change—Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should

- directly measure environmental and human health risk reduction

- improve quality assessment and quality control for key program elements, such as closure, to provide assurance that environmental and human health risks are reduced

- develop a consistent approach for custodians to document and report on key program priorities—such as site closure, climate change, and Indigenous engagement

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

There was a lack of meaningful information and performance measurement for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan

1.42 This finding matters because Canadians need to understand the state of contaminated sites, including their environmental and financial effects. Effective performance measurement helps to meet the program’s objectives and supports decision making, accountability, and open communication that is key to building trust and engaging in nation‑to‑nation reconciliation.

1.43 With support from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Environment and Climate Change Canada publishes annual reports on its website that communicate government‑wide results on contaminated site remediation to Canadians. The information on specific contaminated sites is available in the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory, a central database administered by the secretariat.

Missing and unmet targets for climate change and socio-economic benefits for Indigenous people

1.44 Environment and Climate Change Canada leads the update of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s performance measurement strategy before the start of each phase of the program. However, we found that the department revised the strategy in the first year of the current phase because it did not represent program commitments accurately. This change increased the number of performance indicators from 23 to 60. In the second year, after the initial collection of data, the department identified data consistency and interpretation issues, which affected the development of several targets.

1.45 We found that targets were not established for the newly added performance indicators for Indigenous engagement and socio-economic benefits, despite being key priorities for the current phase. For example, program results show that in 2022–23, the proportion of hours worked by Indigenous peoples on contaminated sites in the North (10,752 of a total of 77,010 hours worked, or 14%) was significantly lower than on reserve lands in the South (27,144 of 55,194 total hours, or 49%). However, without targets for these indicators, it is unknown how the program is progressing with regard to the priority of socio-economic benefits for Indigenous peoples.

1.46 Likewise, we found that Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, did not have indicators to measure and track a group of emerging contaminants of concern called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—known as PFAS or forever chemicals because they remain in the environment for long periods—across sites included in the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan.

1.47 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada did not finalize a northern procurement guidance document for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan by the target date outlined in the program’s performance measurement strategy. The purpose of this document is to improve the involvement of Indigenous communities in the program and set out principles for creating positive social and economic effects for nearby Indigenous communities in northern Canada. At the time of our audit, this document was not complete.

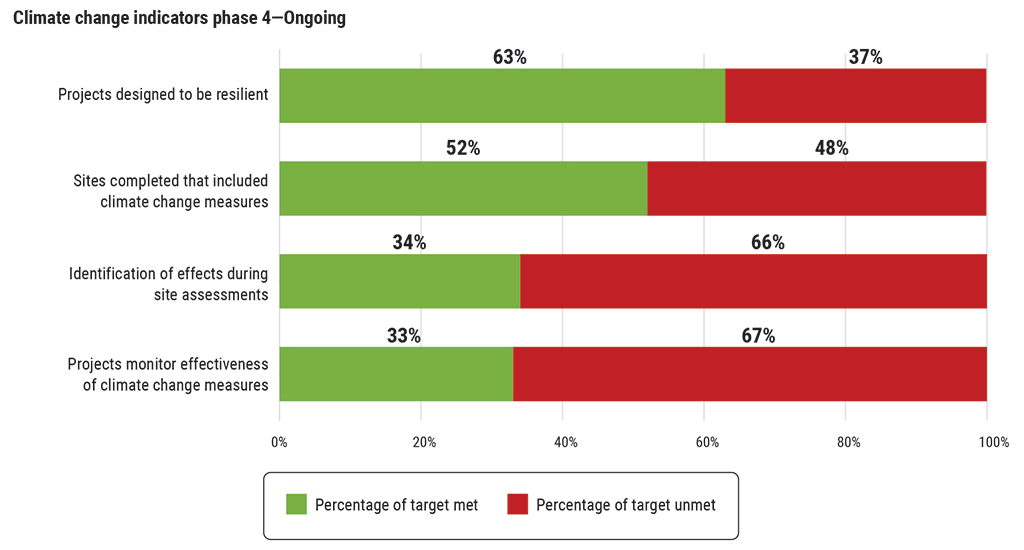

1.48 Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, established several indicators for climate change adaptation, a program priority. However, we found that it considered the annual targets for these indicators to be “aspirational” and that none were close to achieving the 100% annual target (Exhibit 1.6).

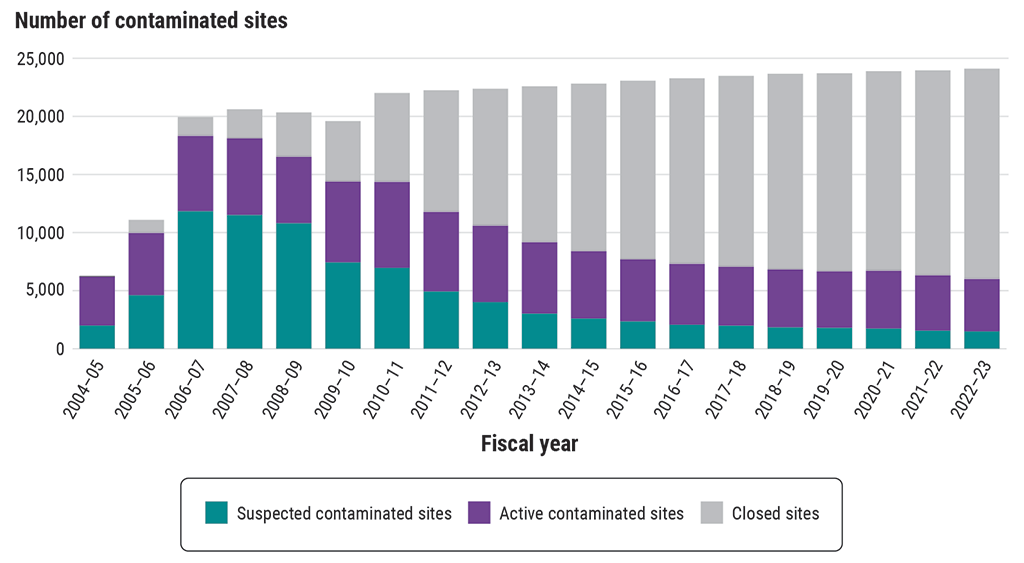

Exhibit 1.6—The Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan annual targets related to climate change were unmet

Note: Due to the lack of an annual target, this graph does not include the climate change indicator for the review of closed sites. The result for this indicator was 52% of the 100% phase target after year 3 of 5.

Source: Adapted from Environment and Climate Change Canada data

Exhibit 1.6—text version

This bar graph shows the percentage of sites that met the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s annual targets related to climate change. It lists 4 climate change indicators for the ongoing phase 4, and for each, it indicates the percentage of the target that was met and the percentage of the target that was unmet. The percentages are as follows in descending order by percentage of target met:

- For the indicator “Projects designed to be resilient,” 63% of the target was met and 37% of the target was unmet.

- For the indicator “Sites completed that included climate change measures,” 52% of the target was met and 48% of the target was unmet.

- For the indicator “Identification of impacts during site assessments,” 34% of the target was met and 66% of the target was unmet.

- For the indicator “Projects monitor effectiveness of climate change measures,” 33% of the target was met and 67% of the target was unmet.

Ensure healthy lives and promote well‑being for all at all ages

Source: United NationsFootnote 1

Ensure access to water and sanitation for all

Source: United Nations

Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

Source: United Nations

1.49 We also found that Environment and Climate Change Canada reported on the primary intended outcomes of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan in its annual report and departmental reporting, but for phase 4, it had not yet reported publicly on program priorities, including

- climate change

- reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and socio-economic benefits in the North, supporting diversity and inclusion and gender-based analysis plus outcomes

1.50 In addition, the department had not produced a formal report on outcomes since the program’s creation in 2005. Doing so would help Canadians, communities, and parliamentarians understand what has been achieved to date and whether the program is working as intended.

1.51 As part of our audit, we examined the departments’ actions to support several United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, such as Goal 3 (Good Health and Well‑Being), Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), and Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), along with selected associated targets. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada, Transport Canada, and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada aligned their site management or remediation activities with some of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal targets through their departmental sustainable development strategies. However, they did not track progress toward meeting United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal targets specifically.

1.52 To improve transparency on contaminated site management and remediation efforts—for all Canadians, but especially for those living in affected communities—Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should improve its performance measurement and reporting for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan by

- maintaining indicators when monitoring and reporting on progress against program objectives and priorities

- clearly reporting publicly on program commitments that are of interest to Canadians and in line with government priorities, such as climate change, reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, and socio-economic benefits

- publicly reporting on progress made toward program outcomes from the beginning

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Limited information on contaminated sites

1.53 We found that the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory, administered by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, did not provide important information. It did not offer enough functionality to be useful for program planning and to provide a clear picture for all Canadians. We found that the inventory was used mainly for financial reporting purposes. Some issues identified included

- an inability to categorize sites by program, as the inventory did not classify sites in terms of their eligibility for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan

- a lack of sufficient details about sites—for example, the reasons for annual adjustments made to liabilities and the current status of sites

- an inconsistency in the consolidation of contaminated sites for projects and some cases of data duplication

1.54 We found that there were no significant technical updates to the inventory since its creation in 2005–06. Furthermore, an internal 2018 evaluation of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan found that the inventory did not compare well with similar registries in provincial and international jurisdictions. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, with support from Environment and Climate Change Canada, did not make changes to the inventory because of insufficient funding.

1.55 We also found that the inventory had no distinct category for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. As a result, custodians were labelling contaminated sites with these substances inconsistently in the system, making it difficult for Canadians to determine the full extent of contamination at federal sites. In addition, we found that the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, with the support of Environment and Climate Change Canada, did not provide guidance to custodians on how to categorize contaminated sites containing per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the inventory.

1.56 To better inform Canadians more accurately and meaningfully about the state of federal contaminated sites, including site‑specific information on their environmental and financial effects, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, working with Environment and Climate Change Canada, should improve the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory by

- identifying which remediation program applies to which sites

- including additional information such as the current status of sites (not just the last step completed), cost adjustments to liability and rationale for increases, actions taken resulting in site closure, and a category for sites with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (an emerging contaminant of concern)

- enhancing transparency by providing more detailed information demonstrating that risk assessments were completed and remediation objectives were met

The secretariat’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Large abandoned mines in the North pose significant costs and environmental risks for current and future generations

1.57 This finding matters because remediation planning for large abandoned mines has led to more accurate estimates of the cost burdening Canadian taxpayers. However, the remediation of these mines represents a significant opportunity to support reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and promote economic development in the region.

1.58 This finding also matters because climate change poses a risk to the effective remediation of large abandoned mines in the North. These remediation projects must be designed for a changing climate. Furthermore, they can cause significant greenhouse gas emissions, which should be avoided and reduced. In addition, the perpetual care requirements of some abandoned mines are a significant concern on many fronts, including

- securing access to long‑term funding

- preserving and accessing records that are critical to managing the site

- ensuring that future generations can access and understand site information and the associated risks to the environment and human health

1.59 From 2005 to 2019, the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan was the primary source of funding for the management of contaminated sites overseen by Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, including large and high‑risk abandoned mine remediation projects.

1.60 In 2019, recognizing the scale, complexity, and risks of these projects, the federal budget allocated $2.2 billion over 15 years for Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada to create a separate program to manage the 8 largest and highest‑risk abandoned mines in its portfolio. The federal budget in 2023 then allocated an additional $6.9 billion over 11 years (2024–25 to 2034–35), bringing the total funding for the program to $9.1 billion over its 15‑year lifespan. The resulting Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program aims to provide the long‑term continuity in funding and authorities and the tailored management approach that these sites require. The remainder of the department’s portfolio of sites in the North remains within the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan.

1.61 In some cases, even after remediation is completed, contaminated sites will require care and ongoing monitoring for an extended period. For example, the department determined that the Giant Mine will require the management of large volumes of arsenic to remain frozen and the Faro Mine will require water treatment and monitoring to prevent contaminated water from polluting the surrounding land and water. For these sites, a site‑specific perpetual care plan will be developed.

1.62 To understand the department’s management of large, high‑risk abandoned mines in the North, we examined the Giant and Faro mines. We chose these 2 due to their high risk, their cost and complexity, their perpetual care needs, and the significant opportunities they present for socio-economic benefits for northern and Indigenous communities.

Significant increases in financial liability for large abandoned mines

1.63 We found that the remediation phase had started for only 1 of the 8 projects under the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program: the Giant Mine. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada officials told us that project costs typically increase gradually until the implementation of the remediation plan. With $1.8 billion in expenditures already incurred, and a further $6 billion in estimated costs remaining, costs should therefore increase further as the other 7 projects advance and enter the remediation stage. The financial liability for these complex sites had increased by 95% since 2019.

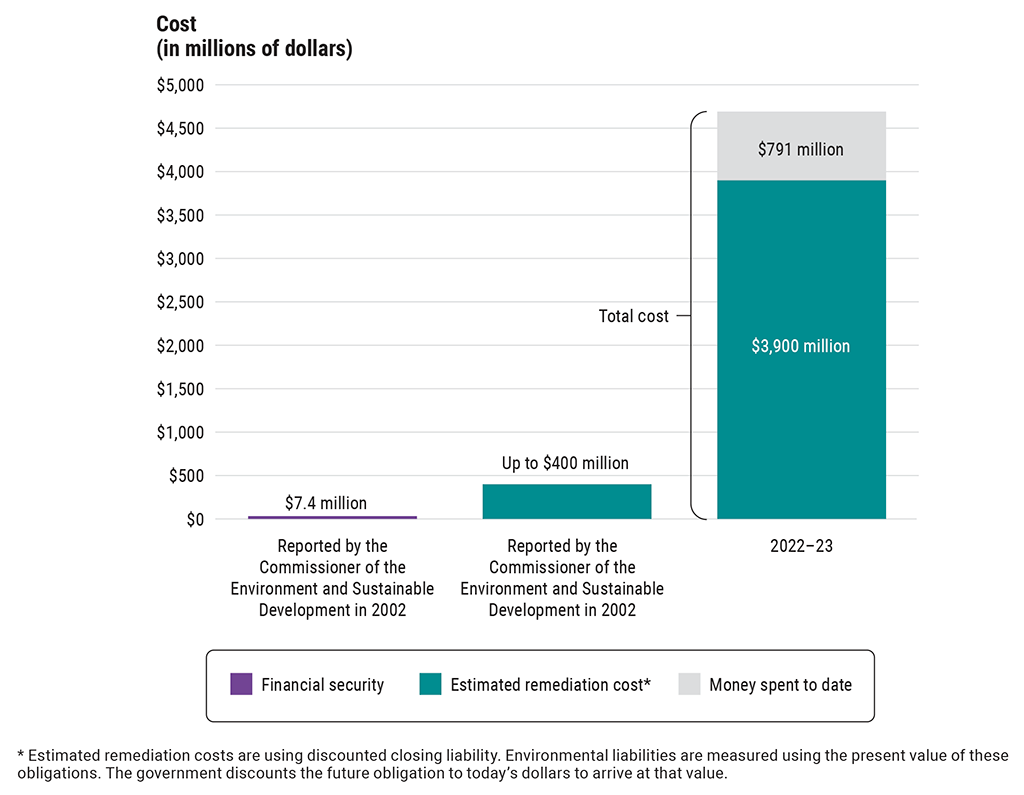

1.64 We also found that since our 2002 audit on large abandoned mines, the contamination at the Giant and Faro mines remained on site, while their financial costs had increased significantly (Exhibit 1.7 and Exhibit 1.8).

Exhibit 1.7—Giant Mine costs rose significantly, and remediation work was not expected to be completed until 3 decades after it was abandoned

Shipping containers filled with contaminants located at the site of the Giant Mine in the Northwest Territories

Photo: Angela Gzowski, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

The Giant Mine is a former gold mine located outside of Yellowknife, in the Northwest Territories. It operated from 1948 to 2004 and was abandoned in 2005. The main environmental concern is the 237,000 tonnes (enough toxic waste to fill seven 11‑storey buildings) of highly toxic arsenic on the site.

The federal government has spent nearly 20 years assessing the site, developing a remediation plan, and conducting consultation and engagement activities. Urgent remediation work was completed during this period to reduce risks to the environment and human health. Remediation officially began in 2021 and is expected to be completed in 2038, 33 years after the mine was abandoned. The site will then require maintenance and monitoring in perpetuity.

The estimated remediation cost for the mine has greatly increased since our 2002 audit, and the total cost to Canadians is much higher.

Source: Adapted from data in the 2002 Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the House of Commons, Chapter 3—Abandoned Mines in the North; and the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory

Exhibit 1.7 chart—text version

This bar chart compares the estimated remediation costs for the Giant Mine as reported by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in 2002 with the estimated costs in the 2022–23 fiscal year.

In 2002, the Commissioner reported that the mine’s financial security was $7.4 million and the estimated remediation cost was up to $400 million. In 2022–23, the estimated remediation cost increased to $3.9 billion with an additional $791 million of money spent to date.

Estimated remediation costs are using discounted closing liability. Environmental liabilities are measured using the present value of these obligations. The government discounts the future obligation to today’s dollars to arrive at that value.

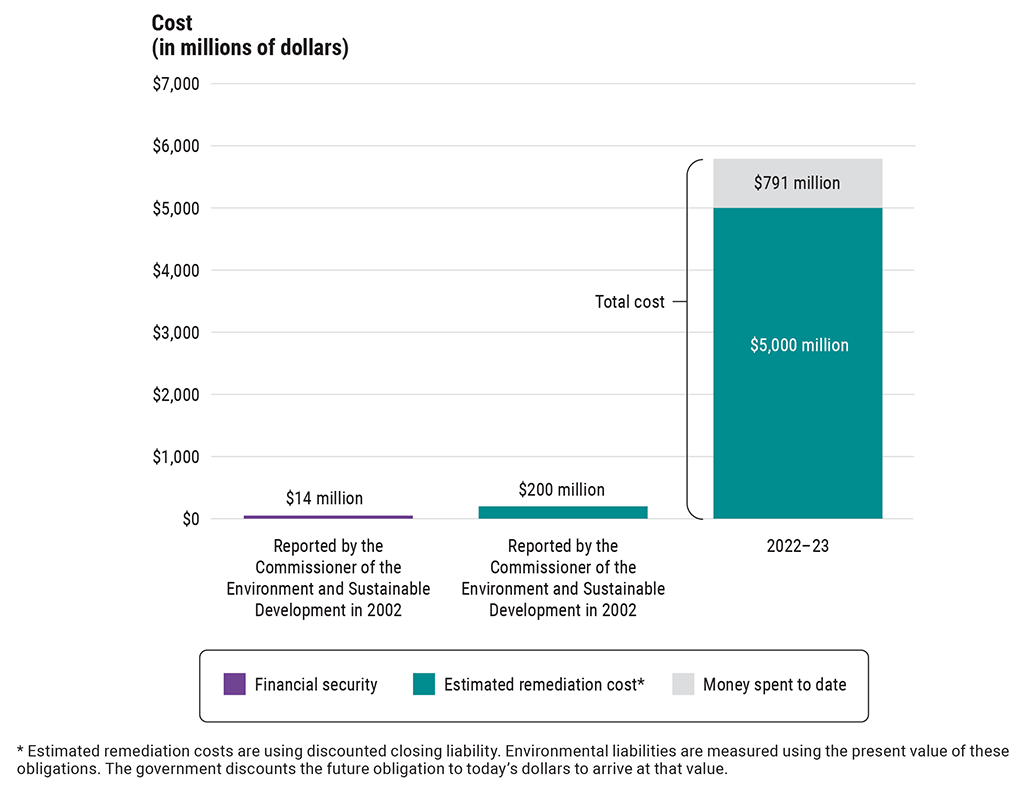

Exhibit 1.8—Faro Mine costs increased significantly, though the remediation phase had not yet started

Site of the Faro Mine in the Northwest Territories

Photo: Daphne Pelletier Vernier, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

The Faro Mine was once one of the largest open‑pit lead‑zinc mines in the world. It began operating in 1969 and was abandoned in 1998. Canada assumed responsibility for the management of the site in 2018. The main environmental problems are mining waste—enough to cover over 26,000 football fields, 1 metre deep—and 3 open pits filled with contaminated water.

At the time of our 2002 audit, the Faro Mine was being assessed. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada had since consulted and engaged with Indigenous communities, conducted urgent remediation work, and submitted the remediation project’s proposal to the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board in 2019 for review. Once designs and regulatory approvals are in place, the remediation of the mine is expected to take 15 years, followed by another 20 to 25 years of testing and monitoring. The site will then require maintenance and monitoring in perpetuity.

The estimated cost to remediate the mine has greatly increased since our 2002 audit, and the total cost to Canadians is much higher.

Source: Adapted from data in the 2002 Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the House of Commons, Chapter 3—Abandoned Mines in the North; and the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory

Exhibit 1.8 chart—text version

This bar chart compares the estimated remediation costs for the Faro Mine as reported by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in 2002 with the estimated costs in the 2022–23 fiscal year.

In 2002, the Commissioner reported that the mine’s financial security was $14 million and the estimated remediation cost was $200 million. In 2022–23, the estimated remediation cost increased to $5 billion with an additional $791 million of money spent to date.

Estimated remediation costs are using discounted closing liability. Environmental liabilities are measured using the present value of these obligations. The government discounts the future obligation to today’s dollars to arrive at that value.

1.65 Our recommendation for this section is at paragraph 1.82.

Limited progress on reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and socio-economic benefits

1.66 We found that Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada developed a socio-economic strategy and accompanying implementation plan for the remediation of the Giant Mine to deliver socio-economic benefits to the region (such as by providing jobs) and to minimize and mitigate any negative social effects. The department had made some efforts in this direction, such as the development of agreements in 2023 with 2 Indigenous groups that included dedicated funding to support capacity development.

1.67 We found that during our audit period, the department had not met its preliminary employment targets for northern and northern Indigenous workers that were developed for the remediation phase of the Giant Mine Remediation Project. For example, in 2022–23, the target range for total hours worked by northern workers was 55% to 70%, but the result was 36%. The target range for northern Indigenous workers was 25% to 35%, but the result was 18%.

1.68 We found that Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada had also begun to develop a socio-economic framework for the Faro Mine. This framework was meant to organize socio-economic commitments for the project, assign clear roles and responsibilities for each commitment, and determine an approach for monitoring progress. The department planned to finalize the framework by March 2021. However, by the end of our audit period, it had not yet done so.

1.69 Nevertheless, we found that the Faro Mine Remediation Project exceeded its internal targets for the amount of training it offers to women, northerners, and Indigenous people during the pre‑remediation phase of the project.

1.70 The remediation of large abandoned mines in the North provides a significant opportunity to advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. However, several Indigenous communities told us that the federal government had missed opportunities to advance on its reconciliation commitments and to leverage these large remediation projects, some of which exceeded a few billion dollars in cost. Specific concerns expressed included

- a lack of meaningful engagement, consultation, and consideration of their input in decision making by the department

- a lack of capacity of the communities and an administrative burden

- a lack of equitable provision and limited to non‑existent socio-economic benefits

1.71 To advance socio-economic benefits and support reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada should

- seek ways to leverage opportunities for Indigenous people to participate in and benefit from the management of contaminated sites in the North

- complete the socio-economic framework for the Faro Mine Remediation Project

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Limited consideration of long‑term sustainability issues

1.72 We found that Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada incorporated climate change adaptation considerations into the closure plan and design process for the Giant Mine Remediation Project. However, several aspects of its approach were lacking. Here are some examples:

- There was no clear documentation of related decisions, such as the rationale for developing climate-related reports, when to reassess climate risks and vulnerabilities, and when to involve key stakeholders.

- There was no formal process with clear timelines or thresholds for reviewing and updating remediation designs in response to evolving predictions of how climate change might affect the project.

- The department had not updated its site‑wide climate change risk assessment for the project.

1.73 We also found that the department had not developed a credible and complete estimate of annual greenhouse gas emissions for the remediation phase of the project. It did make some efforts to reduce emissions by replacing older buildings with more‑efficient infrastructure. However, it had not yet developed an official plan to reduce emissions from the project.

1.74 For the Faro Mine Remediation Project, the department estimated the total greenhouse gas emissions at 194 kilotonnes per year, a 46% increase in the territory’s total. Despite this, we found that the department had not committed to tracking greenhouse gas emissions. In its project proposal for the environmental assessment, the department committed to reducing emissions through activities such as equipment and vehicle maintenance. However, department officials told us that they expected such reductions to be minimal.

1.75 We found that the first draft of the perpetual care plan for the Giant Mine was 3 years behind the finish date named in the environmental agreement for the project. Department officials told us that it was not expected to be completed until 2025.

1.76 We also found that the department had not committed to developing a perpetual care plan for the Faro Mine. Officials told us that the department will commit to developing a plan, including engaging affected Indigenous communities, during the submission for the project’s water licence in 2025.

1.77 Our recommendation for this section is at paragraph 1.82.

Lack of public and timely progress reporting

1.78 The annual reports and the status of the environment reports for the Giant Mine are provided by the Giant Mine Oversight Board on its website. However, because Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada does not mention the oversight board as a key source of project information prominently on its website, Canadians may have difficulty finding up‑to‑date information about progress, plans, and environmental protection efforts related to the mine.

1.79 We found that the department’s reporting on climate change for the Giant Mine was weak:

- The department will not report publicly on changes made to the designs of remediation infrastructure due to updated climate predictions for up to 6 months after the remediation of that component of the site is complete.

- While the department reported publicly on greenhouse gas emissions from the project, it did not develop an indicator for project-level performance on climate change and greenhouse gas emissions from the site. So, this performance could not be reflected in the reporting.

1.80 For the Faro Mine remediation, the department committed to reporting and sharing information on environmental, water quality, and socio-economic indicators through the environmental assessment process for the project. The department has committed to preparing annual reports for the project, starting with 2023–24 activities, despite remediation not being expected to begin before 2029.

1.81 We also found that the department’s website for the Faro Mine Remediation Project was not up to date and did not refer to the regular progress updates that were available on the main construction manager’s website for the project.

1.82 To improve its management of large abandoned mines in the North under the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada should enhance the reliability of the liability estimates and reduce environmental risks and improve transparency for current and future generations by

- engaging an independent expert to carefully review and assess the estimated liability of sites

- updating the Giant Mine Remediation Project’s site‑wide climate change risk assessment and developing or improving short- and long‑term strategies to reduce on‑site emissions

- completing perpetual care plans for the Giant and Faro mines

- reviewing other departmental projects requiring long‑term monitoring and perpetual care that could be more effectively addressed under the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program

- improving the accessibility and quantity of public information on the progress of projects and publishing it more frequently

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

1.83 We concluded that contaminated sites in northern Canada were not effectively managed to meet the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s and the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program’s objectives. Despite work undertaken by departments to assess and remediate contaminated sites, the financial liability had increased significantly since 2005. Gaps remained in practices intended to reduce the risks to the environment and human health for current and future generations.

1.84 Transport Canada and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada managed active contaminated sites in the North in compliance with the requirements of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. However, this did not equate to the achievement of Canada‑wide program targets.

1.85 Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada had made some progress in managing risks to environment and human health under the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. However, contamination remained on site, and some sites will require monitoring in perpetuity.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on contaminated sites in the North. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the management of contaminated sites in the North complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Transport Canada, working with Environment and Climate Change Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, effectively managed federal contaminated sites in the North by reducing the risks to the environment and human health and the associated financial liability for current and future generations.

Scope and approach

The programs we examined included the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. With regard to the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan, where information was not available for the North or appropriate to look at in isolation, we examined the Canada‑wide program measurement, reporting, and results.

We analyzed northern and Canada‑wide data and information obtained from documents provided by the entities and during interviews with department officials. We also used representative sampling for 2 custodians managing contaminated sites in the North (Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Transport Canada) to better understand how medium- to high‑risk northern contaminated sites eligible under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan were managed.

More precisely, our sample included Class 1 or 2 sites according to the National Classification System for Contaminated Sites published by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Moreover, the sites must have at least reached step 6 of the 10‑step process that the government uses to manage contaminated sites. Finally, they must be eligible under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan.

There are 82 contaminated sites managed by Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada that meet the criteria described above. Our sample of 34 of those active contaminated sites allows us to conclude on the sampled population with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error of +10%. We also examined the 5 sites covered by this scope that closed over the course of our audit period. For Transport Canada, we did a census of the 23 active and 6 closed contaminated sites.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Transport Canada has effectively managed contaminated sites under its responsibility through the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan by

Transport Canada has achieved desired results and has reported effectively under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. Transport Canada has monitoring measures in place to ensure long‑term sustainability in managing contaminated sites in the North through the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. |

|

|

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada has effectively managed contaminated sites under its responsibility through the Northern Contaminated Sites Program by delivering the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program in a way that is

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada has achieved desired results and has reported effectively under the Northern Contaminated Sites Program. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada has monitoring and enforcement measures to ensure long‑term sustainability in managing contaminated sites in the North through the Northern Contaminated Sites Program. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada has ensured effective contaminated site management and long‑term sustainability in managing contaminated sites in the North through the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada with support from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat has provided overall program oversight, support, and administration through the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. Environment and Climate Change Canada has achieved desired results, and Environment and Climate Change Canada with support from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat has reported effectively under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 March 2019 to 31 October 2023. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 27 February 2024, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Kimberley Leach, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

Responses appear as they were received by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.26 To achieve the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s objective of reducing the financial liability, Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should support custodians in reducing financial liability by

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada (the department), working with key program partners, will support custodians’ and industry capacity to develop more accurate cost estimates by conducting an analysis of estimation gaps for a variety of projects, reviewing current capacity and practices, providing findings, lessons learned, and recommendations regarding additional improvements to the Federal Contaminated Sites Action plan (the program) interdepartmental governance, including measures such as training, guidance, and access to expertise by March 2027. The department will continue to encourage the use of mechanisms such as interdepartmental transfers, early and collaborative planning, and contingency projects, to reduce the funding carried forward. The department will investigate with partners whether there are any potential additional measures and flexibility mechanisms, within the parameters of the financial administration act and treasury board policies and provide recommendations as part of the renewal of the program for Phase V by March 2025. The department will conduct an analysis on appropriate proportions of assessment and remediation funding for completion by March 2026. |

|

1.41 To achieve the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s objective of reducing the environmental and human health risks, and to support custodians more effectively and make greater progress toward program priorities—such as reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and climate change—Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada (the department) will:

|

|

1.52 To improve transparency on contaminated site management and remediation efforts—for all Canadians, but especially for those living in affected communities—Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should improve its performance measurement and reporting for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan by

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada (the department) will:

|

|

1.56 To better inform Canadians more accurately and meaningfully about the state of federal contaminated sites, including site‑specific information on their environmental and financial effects, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, working with Environment and Climate Change Canada, should improve the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory by

|

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s response. Agreed. TBS will continue to explore funding strategies that would support system improvements. In collaboration with Environment and Climate Change CanadaECCC as program lead as well as custodian departments, TBS will assess the feasibility of adding reporting requirements, whether through the Inventory or other reporting mechanisms. Considerations will include evolving science, program requirements, and maintaining the integrity of the procurement processes. TBS would note that which program applies to which site is currently available. TBS, in consultation with ECCC and custodian departments, will assess alternative ways of reporting which remediation program applies to which site for improved clarity. In addition, TBS is currently in the process of incorporating reporting on a contaminate of emerging concern known as per- and polyfluorinated substances (PFAS) into the Inventory, which is expected to be in place by March 2025. |

|

1.71 To advance socio-economic benefits and support reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada should

|

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s response. Agreed. The department agrees to further advance reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples by continuing to prioritize and, in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples, explore new ways for Indigenous people to participate more fully and benefit from its projects through cultivation of trust, renewed relationships, socio-economic benefits, funding to participate fully in project decision-making (By March 2026) and the establishment of a Faro Project Socio-Economic Committee with, at the pace of, and inclusive of, affected First Nations. |

|

1.82 To improve its management of large abandoned mines in the North under the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada should enhance the reliability of the liability estimates and reduce environmental risks and improve transparency for current and future generations by

|

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s response. Agreed.

|