2021 Reports 3 to 7 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Report 7—Environmental Petitions Annual Report

Focus of the report

The purpose of this annual report is to inform Parliament and Canadians about the number, nature, and status of environmental petitions and responses received from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021, as required by section 23 of the Auditor General Act.

This report also includes 2 case studies which highlight recent actions taken by the Government of Canada on issues raised in the following environmental petitions:

- petition 414 (Concerns about impacts of open‑net fish farming on wild Pacific salmon), which was submitted in March 2018

- petition 417 (Clarification requested on the proposed Icefields Trail in Jasper National Park), which was submitted in May 2018

2020–21 Results

Petitions received and organizational responses provided

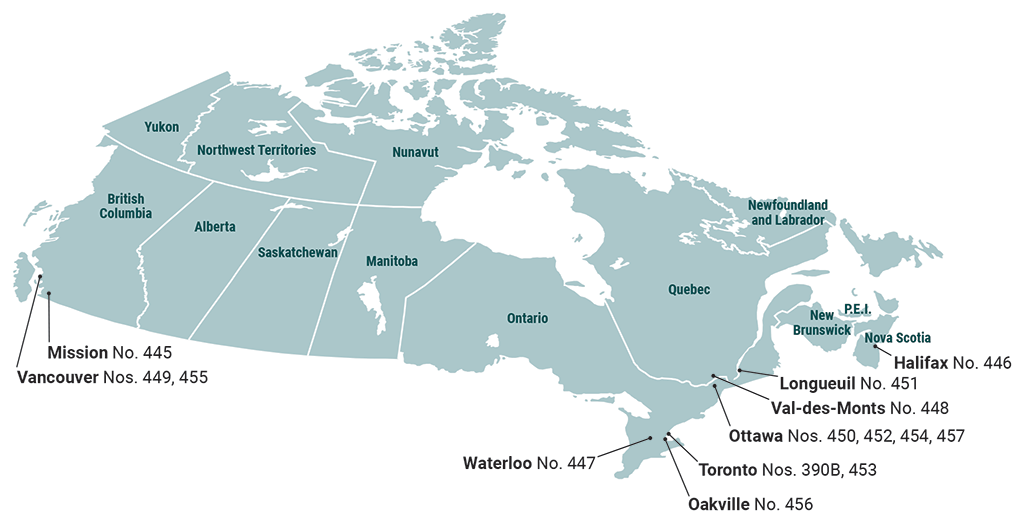

Petitions received. The OAG received 14 environmental petitions from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021. The petitions originated from 4 provinces: British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec (Exhibit 7.1).

Exhibit 7.1—Petitions came from 4 provinces from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021

British Columbia

445—Federal funding for the Fraser Basin Council Society

449—Federal protection of critical habitat for migratory birds

Quebec

448—Acid mine drainage from Gatineau Park and vicinity

451—At‑risk pipelines under the Ottawa River

Nova Scotia

446—Logistics required for deploying newly researched oil spill tools

Source: Petitions submitted to the Auditor General of Canada. Summaries are available on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s website.

Exhibit 7.1—text version

This map of Canada shows the communities that the petitions came from during the period from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021. Petitions came from 4 provinces: British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia.

British Columbia

- Vancouver: Petitions 449, 455

- Mission: Petition 445

Ontario

- Waterloo: Petition 447

- Oakville: Petition 456

- Toronto: Petitions 390B, 453

- Ottawa: Petitions 450, 452, 454, 457

Quebec

- Val‑des‑Monts: Petition 448

- Longueuil: Petition 451

Nova Scotia

- Halifax: Petition 446

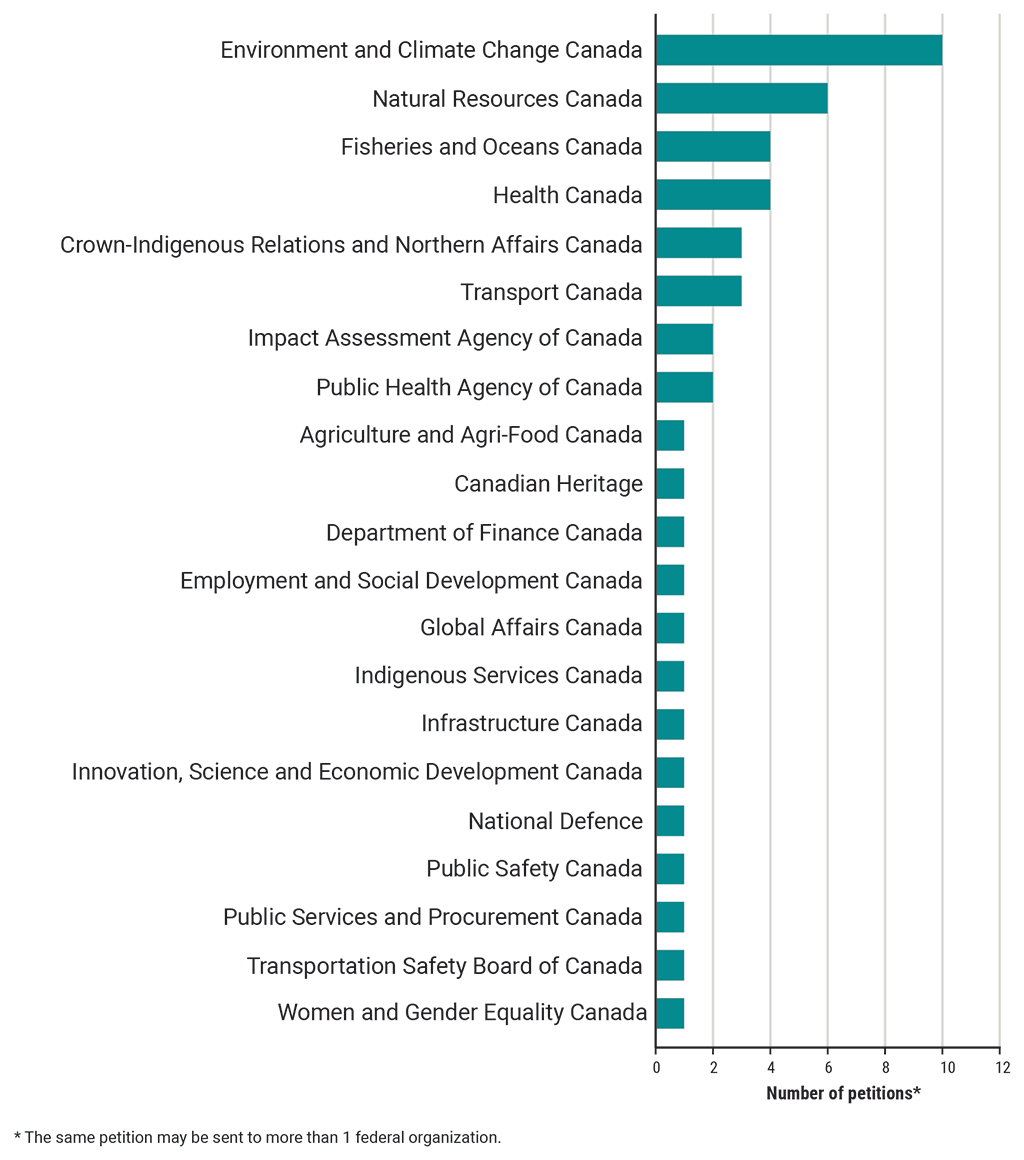

This year, 21 federal organizations received petitions requesting a response. In most cases, petitions were sent to more than 1 federal organization for a response (Exhibit 7.2).

Exhibit 7.2—Twenty‑one federal organizations received petitions from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021

Exhibit 7.2—text version

This bar graph shows the number of petitions that each federal organization received from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada: 10

- Natural Resources Canada: 6

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada: 4

- Health Canada: 4

- Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada: 3

- Transport Canada: 3

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada: 2

- Public Health Agency of Canada: 2

- Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada: 1

- Canadian Heritage: 1

- Department of Finance Canada: 1

- Employment and Social Development Canada: 1

- Global Affairs Canada: 1

- Indigenous Services Canada: 1

- Infrastructure Canada: 1

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada: 1

- National Defence: 1

- Public Safety Canada: 1

- Public Services and Procurement Canada: 1

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada: 1

- Women and Gender Equality Canada: 1

Note: The same petition may be sent to more than 1 federal organization.

The 4 federal organizations that received the most petitions requiring a response were Environment and Climate Change Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Health Canada.

Changes to the Federal Sustainable Development Act and consequential amendments to the Auditor General Act that took effect on 1 December 2020 increased the number of federal organizations that are required to respond to environmental petitions from 28 to nearly 100. Four organizations received petitions for the first time during this reporting year. Three of these organizations—the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, Infrastructure Canada, and the Transportation Safety Board of Canada—were required to respond under these new legislative changes. The fourth organization—Women and Gender Equality Canada—had already been on the list of petitionable organizations.

Key issues raised. The petitions addressed a wide variety of issues, including concerns about biodiversity, climate change, environmental assessment, and toxic substances. Some specific topics included

- federal funding for the Fraser Basin Council Society

- COVID‑19 financial support for the fossil fuel industry

- the impact of fuel emissions on climate change

- the impact of neonicotinoid pesticides on pollinators

- migratory bird habitat

- oil spill response technology

- potential underwater pipeline leaks

- implementation of Canada’s commitments to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals

Responses provided. From 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021, 19 federal organizations responded to 12 petitions. Six of these petitions were submitted during the current reporting period (1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021), and the other 6 were submitted in the previous reporting period (1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020). All but 1 of the petition responses were provided within the 120‑day statutory deadline.

Adding value to the environmental petitions process

Maintaining a public record of environmental petitions. The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development posts summaries of the environmental petitions received in the last 5 years in the Petitions Catalogue on the OAG’s website. Petitions and responses from federal ministers are available on request in the language in which they were submitted. Older petitions are also available on request. The Commissioner submits the Environmental Petitions Annual Report to Parliament in the fall of each year. The OAG maintains these reports on its website for 5 years. Older reports are available through the Government of Canada’s publications database.

Raising Canadians’ awareness of environmental petitions. The OAG uses a variety of communications products to raise Canadians’ awareness of environmental petitions. In addition, the OAG’s employees have reached out to various organizations to share information about the petitions process, answer questions, and provide advice on submitting a petition. For example, they have delivered presentations on environmental petitions to several university classes and to organizations and groups that have expressed interest.

Supporting continuous improvement. The OAG sends a survey to petitioners after they receive responses from federal organizations. This survey allows petitioners to assess and comment on the responses. Petitioners can allow their comments to be shared with officials from those organizations. All petitioners who responded to this survey from January 2020 to June 2021 found the OAG and its petitions-related resources to be satisfactory or very satisfactory. Of these petitioners, 60% rated the petition responses they received from federal organizations to be satisfactory or very satisfactory, while some respondents expressed concern that certain questions were not addressed or answered.

Providing assistance to federal organizations. The OAG provides guidance to federal officials who respond to petitions. With the expansion of the list of organizations required to respond to environmental petitions, the OAG consulted with officials from several organizations that frequently receive petitions as it updated guidance materials for federal officials on the petitions process.

Incorporating petitions into the OAG’s audit work. Petitions and responses are shared with the OAG’s performance auditors. In addition, the OAG considers petitions and responses when developing its multi‑year performance audit program.

Period covered by the report

The annual report on environmental petitions covers the period from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021.

Petitions team

Principal: Michelle Salvail

Director: Marie‑Josée Gougeon

Alison Clarke

Cali Kehoe

Kris Nanda

Karen Webber

Case Studies

Case study: Broughton Archipelago fish farms

Petition 414

Petition 414, submitted in March 2018 by the Wild Salmon Defenders Alliance, raised concerns about the impact of open‑net aquaculture practices on wild salmon and herring species in the Broughton Archipelago of British Columbia. It raised questions around testing for pathogens and sea lice and around the absence of a requirement to test for piscine orthoreovirus (PRV), and it asked about the number of fish farms that remained along wild salmon migration routes.

Background

Salmon aquaculture is a well-established industry in British Columbia, with production in 2019 valued at approximately $708.6 million. While the Government of British Columbia regulates tenures for fish farms and workplace health and safety, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has the lead regulatory role in issuing licences, overseeing aquaculture activities, and monitoring aquatic ecosystems and fish health.

Some members of the public and organizations have raised concerns about how the health of wild fish is being affected by fish farming practices used on the west coast of British Columbia. There were also reports that wild fish were getting access to farmed fish food containing chemicals and were being exposed to farmed fish diseases. In some instances, wild fish were reportedly being entrapped in salmon farms and being eaten by the farmed fish.

The petitioners inquired how Fisheries and Oceans Canada is following the recommendations of the Cohen Commission Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River and taking measures to protect and ensure the health of wild fish stocks. They also asked how the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is applied to aquaculture in the Broughton Archipelago.

Department’s response

The September 2018 response from Fisheries and Oceans Canada to the petition stated that the department was following the precautionary approach, was testing for pathogens throughout the year, had analyzed scientific knowledge around PRV, and concluded that PRV was not harmful to the protection and conservation of fish. The response also referenced Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s implementation in 2016 of a revised siting guide—guidelines for siting aquaculture operations to “minimize the risks to fish health and the aquatic ecosystem.” The response further discussed Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s ongoing commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and highlighted its consultation with First Nations when developing policies and guidelines, like the 2016 siting guide.

Office of the Auditor General of Canada audit

The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development published an audit report on salmon farming in spring 2018. The report found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had not made sufficient progress in completing risk assessments for key diseases. The report recommended that the department determine and communicate how it applies the precautionary approach under uncertainty about the effects of aquaculture on wild fish. The department’s responses to the recommendations can be found in the report, which is available on the website of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

Recent actions on issues raised

In December 2018, the Government of British Columbia announced recommendations, which were developed with local First Nations and agreed on by fish farm operators in the region, to protect and restore wild salmon stocks in the Broughton Archipelago and to create a “farm-free migration corridor.” This provincially led initiative involves the ultimate closure of 17 fish farms over a 5‑year period.

In June 2019, Fisheries and Oceans Canada released its interim Framework for Aquaculture Risk Management for external consultation. This action followed the finding in the Commissioner’s 2018 report that the department did not clearly articulate how it applied the precautionary approach in the face of uncertainties about the effects on wild fish populations. This framework was designed to outline how the department assesses and manages risks associated with aquaculture operations and to explain how it applies the precautionary approach. The updated framework is expected to be publicly posted in fall 2021.

In September 2020, in response to recommendation 19 of the Cohen Commission, the department presented the last of 9 risk assessments of the overall risk to Fraser River sockeye salmon from diseases that can occur from aquaculture operations in the Discovery Islands area.

In addition, the Prime Minister’s December 2019 mandate letter directed the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard to “work with the province of British Columbia and Indigenous communities to create a responsible plan to transition from open net‑pen salmon farming in coastal British Columbia waters by 2025 and begin work to introduce Canada’s first‑ever Aquaculture Act.” The department has indicated that work is underway to develop a transition plan and draft legislation.

Case study: Icefields Parkway bike trail

Petition 417

Petition 417, submitted in May 2018 by the Jasper Environmental Association, raised concerns about the potential effects of constructing a proposed 107‑kilometre trail in Jasper National Park in Alberta. The petition maintained that construction of the bike trail—which would be separated from the Icefields Parkway by up to 30 metres of vegetation—would have adverse effects on the local ecosystem and biodiversity and increase the potential of human–wildlife conflict. Specifically, the petitioner asked whether Parks Canada had considered alternative solutions, like widening the existing biking shoulders of the Icefields Parkway, and how Parks Canada planned to manage invasive weeds and human–wildlife conflicts if the trail were constructed. The petitioner also expressed concerns about the costs of maintaining the trail given the already strained park infrastructure and questioned whether the proposal signalled a shift in favour of new visitor infrastructure over ecological integrity and species at risk.

Background

The Icefields Parkway is a scenic highway connecting the hamlet of Lake Louise in Banff National Park with the town of Jasper in Jasper National Park. As part of Budget 2016, the Government of Canada announced that $65.9 million would be allocated to construct a new bike and walking trail parallel to the Icefields Parkway from Jasper to the Columbia Icefield. In January 2017, Parks Canada launched public and Indigenous consultations and began work on a Detailed Impact Analysis.

According to the petition, the area of the proposed project included critical habitat of 6 species at risk, including a threatened herd of Southern Mountain Caribou, and other sensitive species, such as grizzly bears. The petition maintained that the proposal would result in increased threats to wildlife and critical wildlife habitat, greater risk of negative human encounters with wildlife, and adverse cumulative effects on sensitive species already affected by traffic in the area.

Agency’s response

In its September 2018 response to the petition, Parks Canada stated that the project had not yet reached the detailed design stage. Parks Canada said that ecological integrity was a top priority for the agency and referred to the multi-species approach to action planning that was developed for species at risk. The response also stated that another agency priority was visitor safety, and it mentioned that encouraging Canadians to visit and experience national parks provided deeper connections to nature and history. The response also indicated that several options were being explored but that widening the current highway shoulder was not an option. It added that a draft Detailed Impact Analysis was expected to outline specific mitigation as part of the design and alignment of the trail to reduce the possibility of human–wildlife conflict.

Recent actions on issues raised

In January 2019, Parks Canada announced that, as a result of the initial feedback from the Icefields Trail consultation process and concerns about the potential environmental impact and project costs, the project would not go forward. Approximately 10% of the original $65.9‑million allocation had been spent on initial work for the bike trail before the decision was made to halt the project. The remaining $59.3 million was redirected to priority needs elsewhere in the national park system. This reallocation included $20.9 million for Waterton Lakes National Park of Canada to support its ongoing recovery from the 2017 Kenow Wildfire, with the remainder earmarked to respond to environmental liabilities and other Parks Canada priorities.