2015 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 4—Information Technology Shared Services

2015 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 4—Information Technology Shared Services

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Implementing shared services

- Shared Services Canada did not establish clear and concrete expectations for partners for maintaining service levels

- Shared Services Canada rarely established expectations or provided sufficient information to partners on core elements of security

- Determining transformation progress has been hampered by weak reporting practices

- Shared Services Canada could not accurately determine whether savings were being generated from IT infrastructure transformation

- Implementing shared services

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

Production of our Fall 2015 reports was completed before the government announced changes to names of some departments. The name Environment Canada was changed to Environment and Climate Change Canada. The name Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada was changed to Global Affairs Canada. The name Industry Canada was changed to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. There was no impact to our audit work and findings.

Introduction

Background

Shared services model—A model of providing services whereby functions from several organizations are consolidated into a single entity whose mission is to provide services as efficiently and effectively as possible.

Information technology (IT) infrastructure—All of the hardware, software, networks, and facilities needed to deliver or support IT services.

4.1 Shared Services Canada. Shared Services Canada (SSC) delivers email, data centre, and network services to 43 government departments and agencies in a shared services model. It is also responsible for purchasing IT equipment, such as keyboards, desktop hardware and software, and monitors, for all of government.

4.2 Under its mandate, SSC is responsible for transforming the government’s existing information technology (IT) infrastructure by modernizing, standardizing, and consolidating it to provide services more efficiently and effectively to generate savings for Canadian taxpayers. In this report, we refer to existing or original services and infrastructure that departments and agencies transferred to SSC as “legacy” services and infrastructure.

4.3 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) provides strategic and policy direction for information technology to the Government of Canada as a whole.

4.4 Before SSC was created, each department managed its own IT infrastructure and services based on its unique requirements to provide programs and services to the public. As a result, levels of IT service varied greatly across government. Each department also funded its IT investments from its own budget. Our 2010 audit report on Aging Information Technology Systems indicated that the federal government infrastructure was aging and at risk of breaking down, which could affect the government’s ability to deliver some essential services to Canadians. The report recommended that a plan be developed for the government as a whole to mitigate risks associated with aging IT systems on a sustainable basis.

4.5 In August 2011, the government announced the creation of SSC, which became a department in 2012 through an act of Parliament. The new department was to manage and transform the IT infrastructure of 43 individual departments, including servers, data centres, human resources, and IT budgets. These government departments are now called “partners.” Some of these systems were outdated, were on a variety of IT platforms, and were supported by diverse service management administrations. The IT infrastructure included 485 data centres, 50 networks, and about 23,400 servers.

4.6 Although IT infrastructure is managed by SSC, partners remain responsible for managing their own applications, data, and desktop devices that they use to deliver their programs to the public. As well, partners retain overall accountability and ownership of their own data. To ensure that partners can deliver programs to Canadians, SSC must provide reliable, efficient, and secure infrastructure services.

4.7 When SSC was created, its budget was set based on an approximate amount that its partners used to spend on IT infrastructure per year. SSC also funds itself by charging for other services to partners and other departments on a cost-recovery basis.

4.8 In 2013, SSC developed a seven-year transformation plan to consolidate, standardize, and modernize the Government of Canada email, data centres, and network services to improve service, enhance security, and generate savings. SSC committed to maintain and improve the level of IT services and security during the transformation. As part of its approach to maintaining IT services, SSC committed to maintaining legacy infrastructure. Departments and agencies will depend less on the legacy infrastructure as the individual transformation initiatives are completed.

Focus of the audit

4.9 This audit examined whether Shared Services Canada (SSC) has made progress in implementing key elements of its transformation plan and maintained the operations of existing services. We focused on SSC’s objectives of maintaining or improving IT services, generating savings, and improving IT security, while transforming IT services. We also looked at how the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat assisted and provided governance and leadership on the strategic vision for SSC and how it fits into the government IT landscape.

4.10 SSC began to transform infrastructure and services in 2013 and expects to complete its transformation of government IT shared services in 2020. This audit was an early review of its progress.

4.11 As part of the audit, we consulted the following 7 SSC partners (out of 43) to understand their experiences with the implementation of shared services:

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- Environment Canada

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada

- Industry Canada

- Public Service Commission of Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

4.12 More details about the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Implementing shared services

4.13 Overall, we found that there were weaknesses in Shared Services Canada’s (SSC’s) implementation of government IT shared services to date, specifically in managing service expectations with its partners and in measuring and tracking progress on transformation initiatives and savings.

4.14 SSC did not set clear and concrete expectations with its partners in providing IT infrastructure service to support their services and applications. As a result, it cannot show if and how it is maintaining or improving services since its creation. Reporting to Parliament focused on activities to be undertaken and not performance against targets. As well, SSC provided limited performance information about service levels and security of IT infrastructure to the 43 partners. All of the partners we consulted raised the lack of security reports as a concern because the partners are accountable for the overall security of their programs and services.

4.15 We found that SSC has not developed consistent processes to determine costs and to measure progress and savings. Progress on the two transformation initiatives we examined has been limited, and reporting to SSC’s senior management board on this progress, including the generation of savings, is not clear or accurate. While SSC had some elements of a process to allocate funding to initiatives, it did not have a comprehensive strategy to prioritize and fund its maintenance and transformation activities. Furthermore, SSC faces challenges in accurately determining and reporting total savings. We also found that SSC did not account for partner costs as part of the transition to a shared services model. As a result, the overall financial savings to the government as a whole will remain largely unknown.

Shared Services Canada did not establish clear and concrete expectations for partners for maintaining service levels

4.16 While Shared Services Canada (SSC) committed to maintain the level of services each partner had before the services were transferred to SSC, we found that it did not establish clear and concrete service expectations for how it would deliver services and measure and report on its performance in meeting this commitment. It documented few agreements with partners that articulated clear and concrete service expectations, rarely provided reports to partners on service levels or the overall health of the IT infrastructure, and did not formally measure partners’ satisfaction with the services they received or report on its progress to Parliament.

4.17 In addition, we found that the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) should have provided additional strategic direction for the transformation of government IT services. The IT Strategic Plan for the Government of Canada is still in draft form; therefore, it has not been formally communicated or implemented. The TBS has developed an integrated IT planning process for government that partners have used to establish their IT project priorities and plans.

4.18 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- setting service expectations,

- measuring and reporting on service performance,

- measuring partner satisfaction, and

- IT strategic and integrated planning.

4.19 This finding matters because, as the shared IT services provider for government, SSC needs to understand whether its services meet its partners’ needs. As the recipients of these services, SSC’s partner departments need to have confidence that the levels of IT service they receive from SSC adequately support their ability to deliver services to Canadians. This means that SSC and partners need to have a clear understanding of their business relationship, founded on a common and concrete set of expectations about

- the level of services to be provided,

- how delivery of the service levels will be measured and reported back to partners, and

- how partners will provide feedback to SSC on their satisfaction with the services they receive.

4.20 Without these clear service expectations, neither SSC nor its partners have a clear understanding of whether service levels are being maintained and whether partners’ needs are being met. Without clear service expectations, SSC cannot demonstrate whether it is meeting its commitment to partners.

4.21 Furthermore, it is important that SSC have additional support in the form of strategic guidance from the TBS to help it achieve its mandate.

4.22 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 4.30, 4.31, 4.32, 4.42, and 4.47.

Target—A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program, or initiative is intended to achieve within a specified time period.

4.23 What we examined. We examined whether SSC had in place key elements needed to maintain service levels for partners, including a service strategy, service level agreements, a service catalogue, baselines, and targets. We also looked at whether SSC reported on its performance and measured partner satisfaction. In addition, we looked at how the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat assisted and provided governance and leadership on the strategic vision for SSC and how it fits into the government IT landscape.

4.24 Setting service expectations. As a service provider, SSC needs to set clear and concrete service expectations with its partners in order to manage its service delivery and demonstrate its performance. We found that SSC had elements of a service strategy and had published a service catalogue, but the catalogue contained few details for many of the services. In addition, SSC rarely put in place sufficiently detailed agreements with partners.

4.25 A service strategy articulates an approach to delivering services to users, with a goal of helping the service provider and its users to achieve their objectives. SSC had some elements of a service strategy in place, including a Transformation Plan, Functional Direction, and Service Lifecycle Management Model. These elements address governing principles for managing legacy services as well as the transition to transformed enterprise services. However, SSC did not have an overall service strategy to

- explain how SSC’s approach to shared IT service delivery would meet its partners’ IT service needs, and

- show how SSC planned to meet its objectives of maintaining and improving service levels for partners.

4.26 A service catalogue is a central source of information about the IT services delivered by a service provider, including pricing. Before SSC was created, a government-wide service catalogue did not exist. Although SSC has been in operation since 2011, it did not publish a service catalogue until March 2015. The catalogue included services that would be available after partners migrated to the new transformed IT infrastructure as well as some legacy services that pre-existed SSC. However, the catalogue did not detail many of the services that SSC was responsible for providing to maintain legacy services and infrastructure. Without a sufficiently detailed catalogue of services, partners did not have a clear understanding of

- what types of services they should expect to receive from SSC,

- how services were intended to be used or for what purposes, and

- what level of service to expect.

SSC informed us that it planned to publish more detailed service descriptions in future catalogues.

4.27 A service level agreement is a written agreement between an IT service provider and IT customer that defines the key service targets and responsibilities of both parties. It is important to define targets so that the service provider can measure and report on how its service delivery aligns with its customers’ needs. SSC prepared high-level agreements called “business arrangements” for each of the 43 partners to describe the business relationship between SSC and partners. However, the business arrangements contained only a generic commitment to maintain the level of services each partner had before the services were transferred to SSC and did not document clear and concrete service expectations, such as service level targets or service level roles and responsibilities.

4.28 In addition to business arrangements, SSC had almost 3,000 agreements in place with partners during the period that we audited. We examined 50 of these agreements and found that most were not service level agreements and did not define service level targets or reporting commitments. In addition, more than half of these agreements did not specify service level roles and responsibilities for SSC and partners. The agreements were used mainly to recover costs for services that SSC deemed new or optional and therefore were not covered by funds already appropriated from partners for IT services. Furthermore, few of these agreements specified reporting commitments relating to services. For 10 of these agreements, we requested the reports that SSC had committed to provide to partners. SSC provided reports to partners for only 1 of the 10 agreements, and the reports covered only some of the services committed to in the agreement.

4.29 To illustrate how SSC needs to document clear and concrete service expectations, Exhibit 4.1 shows an example of a critical service outage that occurred when business needs and service expectations between SSC and one of its partners were not clearly documented.

Exhibit 4.1—Case study: Lack of documented service expectations contributed to outage of emergency radio services

On 24 March 2014, for 40 minutes, all first responders in Saskatchewan lost radio voice communications, which were managed by Shared Services Canada (SSC). The outage of emergency radio services was linked to a lack of documented service expectations between SSC and the RCMP.

The Province of Saskatchewan’s emergency radio service is used by over 9,000 first responders (municipal police forces, ambulance, fire, and other provincial emergency services), the RCMP, and provincial agencies. The service is supported by a network switching centre that controls over 250 radio sites, located throughout Saskatchewan, and 13 dispatch centres.

In 2010, the province asked the RCMP to manage the service. In 2011, SSC took over management of the network switching centre. Despite sharing responsibility with the RCMP for the radio service, SSC did not put in place an agreement setting out service expectations, including respective roles and responsibilities for making changes to the radio network. Nor did SSC detail a formal notification process to ensure that both parties were aware of changes to the radio network and of the impacts that these might have on radio services and the continuity of services.

For those 40 minutes on 24 March 2014, police, fire, and emergency medical services throughout Saskatchewan could not send to or receive calls from the dispatch centre and could not talk to each other to declare emergencies and coordinate responses via their radio system. First responders reverted to using their personal cellphones, but cellphone coverage is sporadic and non-existent in some remote communities. The outage was caused when SSC accidentally rendered a critical feature of the radio network unavailable while making changes to the network to conform to its shared services network standard. Had SSC followed an adequate change management process, which would have included proper testing and user acceptance, the RCMP could have ensured that SSC took the necessary steps to avoid the outage.

4.30 Recommendation. Shared Services Canada should develop an overall service strategy that articulates how it will meet the needs of partners’ legacy infrastructure and transformed services.

The Department’s response. Agreed. By 31 December 2016, Shared Services Canada (SSC) will approve and communicate a comprehensive service strategy that sets out how it will deliver enterprise IT infrastructure services to meet the needs of Government of Canada partners and clients. The strategy will reflect SSC’s overall approach to providing legacy and transformed services at defined levels, the role of partners within the strategy, how partner and client needs will be considered and addressed, and how the approach results in the best value to Canadians.

4.31 Recommendation. Shared Services Canada should continue to develop a comprehensive service catalogue that includes a complete list of services provided to partners, levels of service offered, and service targets.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada will establish a service catalogue project to support the evolution of the catalogue’s structure, content, and automation. The catalogue will include more detailed service descriptions, service levels, and associated targets. Catalogue updates will begin in March 2016, and will continue on an ongoing basis as services evolve.

4.32 Recommendation. Shared Services Canada should work with its partners to establish agreements that clearly and concretely articulate service expectations, including roles and responsibilities, service targets, and associated reporting commitments.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada (SSC) will update the existing business arrangements with partners. As part of this update, SSC will establish service expectations for enterprise services that include roles and responsibilities, service targets on key areas of Government of Canada IT infrastructure performance, and partner reporting commitments. SSC will provide these expectations to partners by the end of December 2016.

4.33 Measuring and reporting on service performance. A service provider must monitor and measure service performance to demonstrate that its targets have been met. We found that SSC did not have service baselines, developed few targets to measure its performance, and provided few reports to partners on service performance.

4.34 A service baseline is a standard or level of service that can serve as a comparison. Using service baselines would allow SSC to fully understand its partners’ levels of service that it was to maintain and ultimately replace. We found that SSC did not record baselines when it became responsible for providing IT services to partners. SSC officials told us that they did not create baselines because partners lacked complete information about legacy services from which to create baselines. Although SSC did not have service baselines, it collected trend data on the number of critical service outages that occurred and the amount of time it took to resolve them. However, this data is not sufficient to demonstrate whether existing service levels are maintained unless there is a baseline for comparison. In addition, although an overall trend may indicate how well SSC is managing outages across partners, it does not indicate to individual partners whether their service levels are being maintained. Furthermore, trend data provides a retroactive view of data over time. A baseline and target, however, give an immediate performance measure and would allow SSC to correct any deteriorating service levels.

4.35 Although SSC has reported a downward trend in critical outages from 2013 to 2015, its process for collecting information on outages does not ensure that all outages are reported. The group in SSC that compiles data for the monthly performance report on critical outages to SSC senior management does not confirm internally that it has received reports of all critical outages that have occurred. This limits the group’s ability to challenge the completeness and accuracy of the data before it is reported to senior management.

Mission critical system—An IT system that is essential to the health, safety, security, or economic well-being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government. Examples are the RCMP’s IT systems at the Canadian Police Information Centre and Environment Canada’s real-time 24/7 weather and water forecasting systems.

4.36 Although SSC had developed a list of partners’ critical business applications and systems (CBAS) to prioritize and assess the impact of reported outages, SSC could not provide evidence that its list was agreed to with partners or was complete. In addition, the CBAS list did not include all applications and systems identified by the TBS and partners as mission critical for government and did not list any business critical services for 8 of the 43 partners. SSC explained that, while the TBS list was for prioritizing applications and systems in the event of a disaster or crisis, the CBAS list was for prioritizing outages affecting partners’ daily business. The CBAS list needs to include all applications and systems identified by partners as critical, with partners agreeing whether they are mission critical or critical to daily business operations. This is important to ensure that outages can be prioritized, tracked, and reported for all systems identified by partners as critical.

4.37 We also looked at how SSC reported on its performance to its partners. In industry practice, service providers give regular service reports to their customers that measure performance against service level targets documented in service level agreements. While there are many aspects of a service that can be measured and reported in order to gauge the “health” of IT systems, the industry standard key areas are security, availability, reliability, and capacity.

4.38 We found that SSC had a process in place to report to its partners on transformation initiatives, current projects, critical outages, and risks. However, it rarely reported on service levels and did not report on the overall health of its IT systems. We consulted with seven partners, who stated that the only regular report they received on system health was a report on service outages, which occurs when a service cannot perform its function. Aside from the report on outages, some partners told us they did not receive any other reports from SSC, while others told us that they received some reports, such as regular reports on partners’ electronic storage space. In other cases, partners stated that they requested and received reports from SSC on demand. Reporting on outages is important but, as the only measure of SSC’s performance, it provided a limited view of system health. The outage reports were insufficient to demonstrate that SSC was maintaining legacy service levels.

4.39 We also examined SSC’s practices of measuring and reporting on service performance to Parliament. Annually, federal departments and agencies table in Parliament their departmental performance reports (DPRs), which present the actual performance results achieved against the expected results and related targets set out in their respective reports on plans and priorities (RPPs) for that fiscal year. In the 2014–15 fiscal year, SSC’s RPP contained nine service performance indicators. For most of the indicators, instead of setting targets, SSC stated that it planned to set baselines. As baselines are needed to report on whether SSC is maintaining or improving services, the lack of baselines means that SSC will not be able to report on its achievements in maintaining services as part of its 2014–15 DPR. Furthermore, in SSC’s 2015–16 RPP, instead of including targets, many of the indicators stated that baselines needed to be established.

4.40 Measuring partner satisfaction. Given that partners must receive their IT services from SSC, it is important that SSC have formal and regular ways to measure partner satisfaction so that it can effectively manage its business relationships. In SSC’s 2014–15 Report on Plans and Priorities, three program areas included partner satisfaction as a service performance indicator to be measured by a survey. SSC did not formally set performance targets or measure partners on their level of satisfaction. Therefore, it could not demonstrate if it met partners’ expected outcomes for service delivery.

Email Transformation Initiative—An SSC initiative whose key objective is to reduce 63 legacy email systems to 1 outsourced email service.

4.41 Partners we consulted confirmed that they were not formally surveyed on their level of satisfaction. Rather, at senior management meetings between SSC and the partners, SSC presented its own assessment of partner satisfaction. There was a lack of understanding over who determines the degree of satisfaction, and some partners stated that they disputed SSC’s assessment of their satisfaction. We noted that SSC has developed a survey for partners moving to the Email Transformation Initiative service. However, as of 31 March 2015, only SSC was using the service.

4.42 Recommendation. Shared Services Canada should measure and report to Parliament and partners on key areas of IT system health performance (such as security, availability, reliability, and capacity) and on partner satisfaction. Where partner service is below target, SSC should put action plans in place to remediate levels.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada (SSC) will continue to mature its performance measurement strategies. Results for key areas of IT system health and partner satisfaction will be reported to partners starting in April 2016 and action plans will be implemented if service levels fall below targets. SSC will also provide more comprehensive reporting on IT system health in its reports to Parliament starting with the 2017–18 Departmental Performance Report.

4.43 IT strategic and integrated planning. In implementing government IT shared services, it is important that SSC have strategic and policy direction from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. This is needed for SSC to understand the overall government direction for Information Technology and scope for shared services, and to help SSC achieve the planned outcomes and expected benefits. Leadership and direction from the TBS is also needed to help partners align their strategic plans with government and SSC and to help SSC prioritize competing service requirements from partners.

4.44 The Government of Canada does not have an IT strategy that provides a government-wide approach to IT investments and delivery with the objective of decreasing costs and improving services. The TBS has a draft IT Strategic Plan dated June 2013, but it has not yet been finalized, formally communicated, or put into effect. Such a plan would help SSC to

- inform its direction and priority setting;

- establish where it needs to be more efficient and effective; and

- align its actions with the business of its partners, which is delivering programs and services to Canadians.

4.45 An efficient, integrated planning process is needed to prioritize and balance the demands of 43 partner departments with SSC’s ability to meet those demands. We found that the TBS operates a centralized, integrated database that partners have used to input their project priorities and plans, including demands for SSC services. We noted that SSC has started using the database to make current and short-term planning decisions.

4.46 The TBS and SSC collaborated to establish new committees with senior management representation from partners to help prioritize IT infrastructure projects. However, at the time of the audit, the terms of reference for these committees were not approved and the committees had not yet met formally.

4.47 Recommendation. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should put into effect a completed IT Strategic Plan for the Government of Canada.

The Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will complete the IT Strategic Plan for the Government of Canada by 31 March 2016, and will work with departments and agencies to help them implement the plan once it is approved.

Shared Services Canada rarely established expectations or provided sufficient information to partners on core elements of security

4.48 We found that Shared Services Canada (SSC) rarely established expectations or provided sufficient information to partners on core elements of security. SSC rarely established security expectations in agreements with partners. Outside of its agreements with partners, SSC identified some security expectations in draft security standards for transformed services and in its operations manual. However, there was limited evidence that SSC reported internally or to partners on how it was meeting these expectations. In addition, SSC did not establish clear roles and responsibilities with its partners to adequately support this part of its service delivery.

4.49 Furthermore, we found that SSC did not perform formal threat and risk assessments or corresponding security assurance activities on the infrastructure supporting mission critical systems or existing legacy systems transferred from partners.

4.50 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- establishing expectations for the delivery of secure services to partners, and

- assessing and mitigating risks and informing partners about those risks.

4.51 This finding matters because SSC plays an important role in implementing Government of Canada security policies, directives, standards, and guidelines to ensure the security of government IT shared services. As the government’s IT infrastructure service provider, it is important that SSC collaborate with partners to manage security threats, risks, and incidents to help protect the government’s critical IT-related assets, information, and services. IT security is a key service that SSC is responsible for providing to its partners. Departments are accountable for providing secure programs and services to the public. However, SSC and its partners must work together to safeguard data and ensure that security is integrated in departmental plans, programs, activities, and services. Without sufficient information and reports about the security of the IT infrastructure managed by SSC, partners cannot fully assess whether their systems and data are secure and determine whether any additional safeguards are needed.

4.52 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.63.

4.53 What we examined. We examined whether SSC supported the delivery of secure services to partners by establishing security expectations with partners on security processes and controls, and by reporting to partners on the security of the IT infrastructure and services. We also examined whether SSC followed IT industry standard practices as well as whether SSC addressed the following four core elements of security in its service provision to partners: data security, infrastructure and application security, incident management, and identity and access management. Our focus was on SSC’s commitment to establish expectations and provide sufficient information on IT security to partners in order for them to meet their accountabilities under the Government of Canada security policies. We did not test whether security controls, such as those addressing the confidentiality of data, were implemented.

4.54 Establishing expectations for the delivery of secure services to partners. We found that some of the 50 SSC agreements with partners we examined specified security roles and responsibilities. However, none of the agreements contained commitments to fulfill and report on security expectations.

4.55 Almost half of these agreements referred to SSC General Terms and Conditions, which included a commitment to conduct security assessments and report findings and recommendations to the partner. To assess whether SSC met this commitment, we asked to review a sample of three security assessments, but they did not exist. We also asked SSC whether it had documented security expectations outside of its agreements. SSC had drafted security standards and documented an operations manual that covered some commitments for securing services, but it did not report to its partners or internally on how it meets these commitments.

4.56 In addition, SSC did not adequately define roles and responsibilities to manage security with partners nor did it sufficiently engage them in managing security expectations. Operational security standards to adequately support this part of its service delivery were not finalized. Reporting to partners was limited to the number of critical incidents for a 12-month period, and indicators were not established for the other areas of security within the scope of our audit. We noted that SSC participated in other Government of Canada committees to establish security standards and architecture.

4.57 Assessing and mitigating risks and informing partners about those risks. One of the four core elements of security is infrastructure and application security, which includes managing risks. Managing risks involves identifying threats and risks to IT infrastructure and ensuring that measures are in place to mitigate those risks. Government of Canada standards and guidelines on security require departments to perform threat and risk assessments and implement measures to mitigate identified risks. As the IT service provider for 43 federal partners, SSC should collaborate with partners to manage security risks to help protect the government’s assets, information, and services.

4.58 Our examination of 50 agreements (see paragraph 4.54) found that almost half made a commitment to assess security risks and report findings and recommendations to the partner. We consulted seven partners and they stated that they received limited information upon request to allow them to assess security risks to the applications and data they used to deliver public programs and services.

4.59 For legacy systems, including mission critical systems, SSC has committed in various official documents to maintain security levels that were originally implemented by partners before being transferred to SSC. We noted that SSC recently planned to perform risk assessment activities on legacy systems and define a process to work with partners. However, we found that it did not have adequate documentation on assessing and mitigating security risks for the infrastructure supporting legacy systems, including mission critical systems.

4.60 SSC provided us with files relevant to its work on nine transformation initiatives at various stages of implementation. We found some documentation on assessing and mitigating security risks, but it was incomplete or missing in many cases. For one of these initiatives, SSC completed a risk assessment for one deployment of Wi-Fi in a specific location, but we found no evidence that it did the required testing of mitigation measures, or that it did risk assessments of other Wi-Fi deployments.

4.61 In addition, we reviewed the documentation on assessing the security of the Email Transformation Initiative (ETI) and ensuring that risks were understood before approval. We found that SSC had conducted a comprehensive security assessment and had begun a privacy impact assessment, which is an assessment of possible risks to privacy of any government service delivery. The ETI service was conditionally authorized by an SSC senior executive before the service was deployed to partners in February 2015. However, the initial release was authorized for partner use with two high risks that SSC planned to mitigate during a subsequent release. We were informed after the examination period that SSC had addressed the two high risks in July 2015. We noted that the privacy impact assessment was not completed during the examination period.

4.62 The seven partners we consulted stated that, in general, they had little involvement with SSC on the security of transformation initiatives and that generally there was a lack of coordination and information exchanged about risk assessments and security assurance activities for all services. These partners had little knowledge or understanding of the safeguards that SSC implemented to make risks to IT infrastructure acceptable. Although generally this was the case for the security of transformation initiatives, for ETI, partners were given an information guide and briefings on security controls and were invited to review details of the security assessment.

4.63 Recommendation. In order for partners to comply with government IT security policies, guidelines, and standards, Shared Services Canada should establish expectations and provide the necessary information to partners for the IT infrastructure and services that it manages.

The Department’s response. Agreed. To help partners carry out their IT security responsibilities, Shared Services Canada will

- establish expectations related to security roles and responsibilities following the renewal of the Treasury Board Policy on Government Security; and

- provide partners with documentation on the security of enterprise services, including security assessment and authorization evidence and partner-specific security incident reports.

Determining transformation progress has been hampered by weak reporting practices

4.64 We found that, for the two transformation initiatives we examined, Shared Services Canada (SSC) made limited progress and some of the information reported to senior management was inadequate. We found that reports

- contained unreliable information to measure progress, and

- lacked information on whether transformation initiatives had achieved their expected benefits.

4.65 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- accuracy of reported data and progress on transformation, and

- practices to manage benefits from transformation initiatives.

4.66 This finding matters because SSC senior management needs reliable reports to measure progress on its transformation initiatives so that it can make informed decisions about

- what remains to be done to complete the transformation,

- how to allocate its resources, and

- what corrective actions are needed to successfully complete the transformation of government IT infrastructure by 2020.

4.67 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.74.

4.68 What we examined. We examined whether SSC reported on progress against its transformation plan and managed the expected outcomes and benefits of transformation.

4.69 Accuracy of reported data and progress on transformation. SSC was created in 2011 and it developed a transformation plan in 2013. The plan covered estimated investments and planned savings associated with its mandate to rationalize and consolidate email, data centres, and network services for its 43 partners. The progress against the plan is reported monthly to SSC’s senior management board, which is its senior executive decision-making body. It therefore needs to have accurate data about SSC’s progress against its plan. Our examination work focused on the 2013 transformation plan, but we were informed by SSC during the examination period that the plan was being revised.

4.70 In the two initiatives we examined, we found that the data used to report on transformation progress in one was acceptable for management decision making and in the other was unreliable or without basis. In both cases, we found that progress on the initiatives was limited.

- Email Transformation Initiative (ETI): During our examination period, SSC began migrating emails under its ETI. The first report to its senior management board after the migration began reported sufficiently on the number of migrated email mailboxes to date. As of the end of March 2015, SSC reported to its senior management board that it had migrated about 3,000 mailboxes to the new email service. However, SSC had planned to complete its migration of more than 500,000 mailboxes by that date.

- Data Centre Consolidation initiative: As for SSC efforts to consolidate or close data centres, there were discrepancies in the data that SSC used to report on progress. The final 2014–15 fiscal year report to the SSC’s senior management board stated that there were 436 of an original 485 data centres still operating. The target is to reduce that number to 7 data centres by 2020. We reviewed project documentation for the data centres that were reported as closed (meaning that data is no longer being processed there) or decommissioned (the site is fully closed and the floor space returned to other uses) for the 2014–15 fiscal year. We found that there was insufficient supporting evidence to meet the criteria of closure or decommissioning.

As of the end of March 2015, SSC reported to its senior management board that it had migrated 100 applications out of about 15,600 to new data centres and eliminated over 300 servers out of about 23,400 as part of the Data Centre Consolidation initiative. SSC did not have the information we required to be able to confirm the number of applications transferred to the new data centres or that the number of servers in use had decreased.

4.71 Practices to manage benefits from transformation initiatives. Under the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Outcome Management Guide and Tools, it is good practice to establish benefits management practices to identify, plan, and track the desired benefits from initiatives. This approach aims to ensure that expected benefits are clearly defined and periodically measured using a structured approach.

4.72 In business cases and other documents, SSC identified benefits and savings it expects to achieve through its transformation initiatives. For example, it planned to measure its progress and success according to how many data centres were closed and how many mailboxes were migrated to the new email system. For the transformation initiatives that we examined, an important expected benefit from transformation was increased cost effectiveness for SSC partners. However, there were no baselines or targets associated with this benefit.

4.73 In addition, the information reported to the senior management board to assess progress in realizing expected benefits for transformation was limited. The reported information did not align with the metrics identified in the SSC benefits realization plans and tools that we reviewed. For example, the monthly reports on the Email Transformation Initiative reported only on the monthly number of users and mailboxes migrated, whereas SSC’s benefits management tools for this initiative included several additional metrics that were not reported on, such as cost savings from migration and the number of security incidents related to email data. In March 2015, SSC developed a draft benefits management framework to understand the scope of benefits for its transformation program areas. Without consistent practices to ensure that these benefits are reported on, SSC cannot demonstrate whether its transformation progress is achieving the original benefits identified.

4.74 Recommendation. Shared Services Canada should reassess the reporting process for its transformation initiatives to

- ensure that methods for measuring progress are defined and aligned to key benefits established at the outset of the initiative, and

- establish review mechanisms to ensure that information reported to the senior management board on the status of transformation initiatives is clear and accurate.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada (SSC) will further develop its benefits management framework to align to the key benefits stated when SSC was created and to include methods for measuring progress. In addition, SSC will review and confirm its key performance indicators to assure the accuracy of the progress against the Transformation Plan. The benefits management framework will be completed by December 2016.

SSC will improve its reporting and review mechanisms to ensure that the information on progress against transformation initiatives is reliable, clear, and meets the needs of its internal oversight bodies. This will be completed by December 2016.

Shared Services Canada could not accurately determine whether savings were being generated from IT infrastructure transformation

4.75 We found that Shared Services Canada (SSC) did not have consistent financial practices to accurately demonstrate that it was generating savings. A funding strategy to prioritize and fund the maintenance of existing services as well as the transformation of services has been developed but not fully implemented. There was also no standard costing methodology in place to determine savings. There were incomplete baselines to measure total savings generated and, where financial baselines were available, SSC was challenged to validate their accuracy. Moreover, partner costs were not accounted for in determining overall savings for the government as a whole.

4.76 Furthermore, we found that SSC has made some progress to improve its governance and oversight of efforts to meet its mandate to generate savings. A new committee was recently created to oversee the realization of savings. Nonetheless, some internal reports on the progress of transformation to senior management lacked data to support the costs and savings being reported.

4.77 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- funding strategy,

- standardized cost management practices,

- financial baselines,

- partner costs, and

- governance and oversight.

4.78 This finding matters because SSC spends about $1.9 billion each year to deliver IT services to partners, invest in projects, and fund its operations. As part of its mandate, SSC is expected to generate savings and efficiencies. Consistent financial practices are needed to ensure the accuracy of reported or estimated savings. Without such practices, it is unclear whether SSC is achieving savings from transformation, and it will not be able to demonstrate that its investments have yielded the expected savings. In addition, without accounting for the full costs of partner investments and activities in a shared services model, the impact on government-wide savings will remain largely unknown.

4.79 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 4.85 and 4.98.

4.80 What we examined. We examined whether SSC established consistent financial practices to demonstrate that it was generating savings. We also examined whether it considered appropriate costs when calculating and reporting savings and whether it defined its objectives and responsibilities for generating savings.

4.81 Funding strategy. SSC expects to fund its transformation initiatives and to operate and maintain legacy services until these services are fully transformed, as expected by 2020. Given the complexity of supporting the legacy and transformation needs of 43 partners, a funding strategy would be an important tool to help SSC meet its service priorities and mandated responsibilities. A funding strategy tailored to support a shared services model would also help SSC to link its priorities with a sustainable way to achieve savings and to resolve any risks that could result in funding deficiencies.

4.82 We examined various plans that relate to how SSC allocates its spending. SSC has a plan for its transformation investments and a five-year Departmental Investment Plan to oversee its investment portfolio. It also had an annual Capital Plan for the 2014–15 fiscal year for allocating funding to some of its project investments. However, these plans did not have clearly established criteria and rationales for how it allocates and prioritizes its available funding to its activities, such as legacy IT services and transformation projects.

4.83 In addition, since SSC’s creation in 2011, it has not had a clear process to ensure that it has the available funding to meet all of its investment needs. In early 2014, SSC recognized a risk that it would not generate the savings it had planned from transformation. In October 2014, it identified priorities to address its funding shortfalls, including

- finalizing negotiations with partners on outstanding and expected funding transfers, and

- improving cost-recovery processes to ensure alignment with the actual costs of SSC services being provided.

4.84 As of May 2015, some progress has been made with the above identified priorities. We encourage SSC to continue its efforts to improve these processes.

4.85 Recommendation. In supporting its funding strategy for its ongoing operations and investments, Shared Services Canada should include in its strategy

- a formal methodology to prioritize and allocate funding for its investments in legacy and transformation initiatives that includes detailed criteria and rationales, and

- a clear process to ensure that it has the available funding to address its funding deficiencies.

The Department’s response. Agreed. To support an update to the Transformation Plan in fall 2016, Shared Services Canada (SSC) will document the methodology it uses to allocate funding for its investment in legacy and transformation initiatives, including its prioritization methodology, detailed criteria, and rationale.

SSC’s Service Pricing Strategy will align the funding strategy to the Government of Canada’s service requirements. SSC formed a Chief Information Officer–Director General Pricing Strategy Committee in April 2015 to assist in the development of pricing strategies for SSC services. Mobile devices and email service pricing strategies were approved in June 2015 and are currently being implemented. Pricing strategies for the remaining 20 services will be approved by December 2016. The Service Pricing Strategy will be reviewed annually by SSC senior management as part of the planning cycle.

4.86 Standardized cost management practices. Standardized cost management practices provide methodologies and tools to allow SSC to produce consistent, timely, and accurate cost information. This can support its reporting and decision-making requirements, and help to more accurately determine savings for its transformation initiatives.

4.87 We found that SSC did not have such standardized cost management practices in place. For example, for three SSC transformation initiatives, forecasted cost information was based on inconsistent costing models and the methodology and practices to create these models were not documented appropriately. In these cases, SSC analysts used different assumptions in their models to estimate salary costs. In 2014, however, SSC started developing an enterprise cost management framework and set up several committees to guide its progress. At the time of our examination, the framework and its related costing tools were still in development.

4.88 Financial baselines. Complete and accurate financial baselines show the initial costs of operating the IT services of the 43 partners. Baselines are needed to compare against SSC’s ongoing costs to determine the total savings generated through transformation. We examined whether SSC had financial baselines and whether they were validated.

4.89 We noted that SSC has financial baselines for its key transformation initiatives. They were established through a review of IT infrastructure costs across all government departments in 2010, which was coordinated by the Privy Council Office and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. As part of the review, IT expenditure information from partners was gathered using 2009–10 fiscal year costs. These costs formed most of SSC’s initial funding.

4.90 We also examined whether SSC validated the IT service cost information in its financial baselines that it inherited from its partners. We found that SSC had incomplete financial baseline information for partners’ costs of delivering IT services. In late 2011, SSC tried to validate some data received from partners. However, it found that the supporting information varied from department to department and did not allow for meaningful interpretation and validation. Where financial baselines were available for those services we examined, SSC was unable to show how they were validated for relevance or accuracy.

4.91 Partners we consulted said that the method used to establish the amount of funds transferred for SSC to manage IT services did not necessarily correlate with partners’ actual IT expenditures. SSC recognized that the 2009–10 fiscal year baseline costs that were used to set its budget, as provided to central agencies by each partner, were an estimate of the actual operating costs for those services. As a result, SSC is now challenged to accurately determine and report savings.

4.92 Partner costs. We found that partner costs were not accounted for in determining savings for the Government of Canada as a whole. For example, these costs can include administrative and project costs incurred by partners in order to work with SSC. All of the partners we consulted identified incremental costs or had planned project costs for migrating to SSC’s transformed IT solutions. For example, one partner identified about $3 million in overhead costs for the 2013–14 fiscal year to coordinate its work with SSC. Another partner identified planned IT expenditures of at least $24 million for the 2014–15 fiscal year to migrate its legacy applications to a future SSC platform.

4.93 Without accounting for the full costs of partner investments and activities, a significant portion of the cost estimates affecting savings are largely unknown. We encourage SSC to acknowledge that these additional costs from partners exist when reporting savings. Exhibit 4.2 illustrates a case where the lack of consistent practices for costing resulted in inaccurate and incomplete reported savings from one initiative.

Exhibit 4.2—Case study: Shared Services Canada did not account for partner costs in determining savings for implementing the Email Transformation Initiative

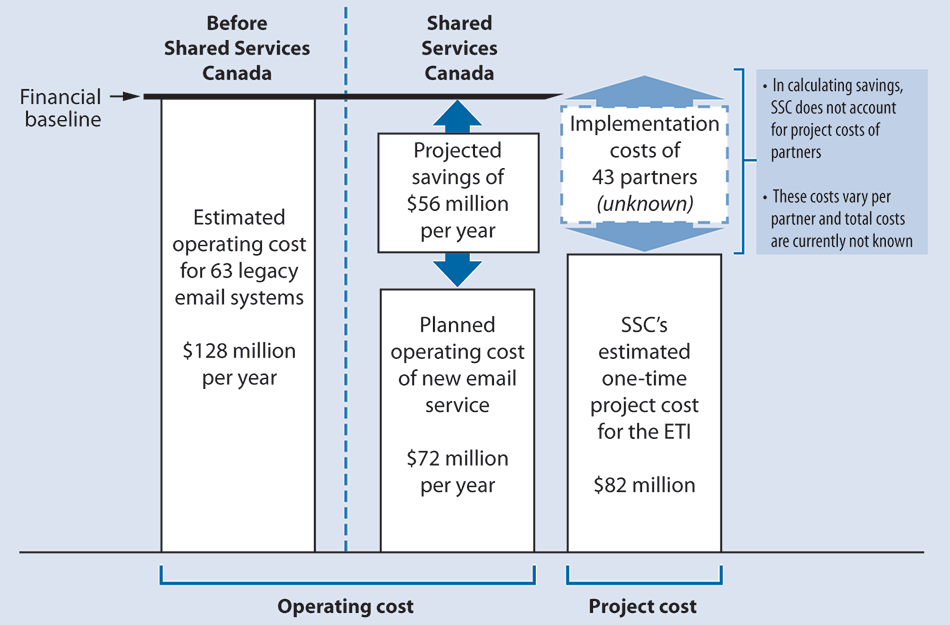

The Email Transformation Initiative (ETI) is a three-year project with a capital investment budget of $82 million and an original expected completion date of 31 March 2015. Shared Services Canada’s (SSC’s) 2013 business case for the ETI stated that $128 million was the annual cost to operate the existing legacy email systems. Under the new email system, an annual operating cost of $72 million was originally estimated, resulting in projected, ongoing annual savings of about $56 million per year once the ETI is fully implemented and all existing legacy email systems are decommissioned.

Selected partners we consulted identified a cost ranging from about $170,000 to $7.7 million each to fund the migration to the new email system. These cost estimates could include application integration costs, desktop upgrade costs, and project management. SSC did not include these project costs in its estimates. A recent independent review in July 2014 of the ETI that was commissioned by SSC found that the unaccounted costs incurred by partners to implement the ETI could range from $500,000 to $5 million each.

While the ETI project has been delayed for over a year, the proposed $56 million in ongoing savings were reduced from SSC’s budget starting in the 2015–16 fiscal year. This commitment is what SSC considers savings achieved from the initiative even though the project has not yet been fully completed.

Exhibit 4.2—text version

The diagram shows that before Shared Services Canada was created, the estimated operating cost for 63 legacy email systems was $128 million per year. The $128 million is considered the financial baseline.

After Shared Services Canada was created, the planned operating cost of the new email service was $72 million per year. The diagram shows that the difference between $72 million and the $128 million financial baseline would mean projected savings of $56 million per year.

Shared Services Canada’s estimated one-time project cost for the Email Transformation Initiative is $82 million. However, the implementation costs of the 43 partners are unknown. In calculating savings, Shared Services Canada does not account for project costs of partners. These costs vary per partner and total costs are currently not known.

4.94 Governance and oversight. We found that, since SSC’s creation, there have been some improvements in the governance and oversight to support the review and realization of its projected financial savings. This included the oversight needed to challenge costs and track savings identified in its transformation initiatives and its reported progress.

4.95 In forecasting savings for transformation, SSC’s Finance Branch had a role in reviewing financial models to ensure consistency in financial information, including projected savings. However, we noted that this role was limited to the initial creation of these models by transformation initiatives and that there was no methodology describing this challenge function. At the time of examination, we were aware of the creation of a new senior management sub-committee to review identified financial benefits to ensure that savings can be realized.

4.96 In addition, one of the responsibilities of SSC’s Transformation Program Office was to work closely with SSC’s Finance Branch to ensure that transformation initiatives were actively tracked for financial benefits. However, the Transformation Program Office’s monthly reports to SSC’s senior management board included no data or information on costs and savings. A draft action plan was under way to develop a financial tracking system to address some of these issues.

4.97 Without consistent practices to determine savings, including structured governance and oversight responsibilities, total savings generated from SSC’s investments and activities for the government as a whole will remain largely unknown.

4.98 Recommendation. Shared Services Canada should periodically refine its methodologies and practices to enable it to accurately determine and report savings.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada will refine its methodologies and practices for determining savings to support an update to the Transformation Plan in fall 2016.

Conclusion

4.99 We concluded that, for the transformation initiatives that we examined, Shared Services Canada (SSC) has made limited progress in implementing key elements of its transformation plan, and it has challenges in adequately demonstrating that it is able to meet its objectives of maintaining or improving IT services and generating savings. SSC did not establish clear and concrete expectations for how it would deliver services or measure and report on its performance in maintaining original service levels for its 43 partners. SSC rarely established expectations or provided sufficient information to partners to help them comply with government IT security policies, guidelines, and standards. In addition, SSC’s reporting against its transformation plan requires improvements because internal reports were not clear or accurate. Furthermore, although SSC has reported that it is generating savings, it does not have consistent practices in place to demonstrate that government-wide savings are being achieved or to recognize that there are partner costs involved in all transformation projects.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of Shared Services Canada (SSC) to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

This audit examined whether SSC has made progress in implementing key elements of its transformation plan and maintained the operations of existing services.

Scope and approach

Shared Services Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat were subject to the audit. We also sought input and experiences from other federal institutions as part of the audit in the areas of security and services.

This audit assessed

- the progress on key elements of the SSC transformation plan,

- how SSC has maintained services transferred from departments and agencies,

- how SSC has maintained the security of IT infrastructure for which it is responsible,

- whether SSC has plans and practices in place to generate financial savings, and

- whether the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat assisted and provided governance and leadership on the strategic vision for Shared Services Canada and how it fits into the government IT landscape.

Entities

A select number of the 43 partner departments were consulted in the audit. The entities selected were Canada Revenue Agency; Employment and Social Development Canada; Environment Canada; Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada; Industry Canada; Public Service Commission of Canada; and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Matters beyond the scope of the audit

This audit did not examine

- human resource skills and transfer of full-time equivalent positions to SSC;

- services to clients of SSC (clients are a separate group of entities that obtain services on a cost-recovery basis but that are not mandated to obtain services from SSC);

- detailed project management progress on transformation programs; and

- the effectiveness of SSC’s security controls.

Criteria

To determine whether Shared Services Canada has made progress in implementing key elements of its transformation plan and maintained the operations of existing services, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Shared Services Canada has maintained the existing level of services for the partners while transforming the IT infrastructure. |

|

|

Shared Services Canada has provided the required security service for the partners within its mandate. |

|

|

Shared Services Canada has made progress and reported on its transformation plan. |

|

|

Shared Services Canada has plans and practices in place to generate net financial savings since its creation. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between August 2011 and May 2015. Audit work for this report was completed on 29 September 2015.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Nancy Cheng

Principal: Martin Dompierre

Director: Marcel Lacasse

Jan-Alexander Denis

Jocelyn Lefèvre

Joanna Murphy

Evrad Lele Tiam

William Xu

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Implementing shared services

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.30 Shared Services Canada should develop an overall service strategy that articulates how it will meet the needs of partners’ legacy infrastructure and transformed services. (4.16–4.29) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. By 31 December 2016, Shared Services Canada (SSC) will approve and communicate a comprehensive service strategy that sets out how it will deliver enterprise IT infrastructure services to meet the needs of Government of Canada partners and clients. The strategy will reflect SSC’s overall approach to providing legacy and transformed services at defined levels, the role of partners within the strategy, how partner and client needs will be considered and addressed, and how the approach results in the best value to Canadians. |

|

4.31 Shared Services Canada should continue to develop a comprehensive service catalogue that includes a complete list of services provided to partners, levels of service offered, and service targets. (4.16–4.29) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada will establish a service catalogue project to support the evolution of the catalogue’s structure, content, and automation. The catalogue will include more detailed service descriptions, service levels, and associated targets. Catalogue updates will begin in March 2016, and will continue on an ongoing basis as services evolve. |

|

4.32 Shared Services Canada should work with its partners to establish agreements that clearly and concretely articulate service expectations, including roles and responsibilities, service targets, and associated reporting commitments. (4.16–4.29) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada (SSC) will update the existing business arrangements with partners. As part of this update, SSC will establish service expectations for enterprise services that include roles and responsibilities, service targets on key areas of Government of Canada IT infrastructure performance, and partner reporting commitments. SSC will provide these expectations to partners by the end of December 2016. |

|

4.42 Shared Services Canada should measure and report to Parliament and partners on key areas of IT system health performance (such as security, availability, reliability, and capacity) and on partner satisfaction. Where partner service is below target, SSC should put action plans in place to remediate levels. (4.16–4.23, 4.33–4.41) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada (SSC) will continue to mature its performance measurement strategies. Results for key areas of IT system health and partner satisfaction will be reported to partners starting in April 2016 and action plans will be implemented if service levels fall below targets. SSC will also provide more comprehensive reporting on IT system health in its reports to Parliament starting with the 2017–18 Departmental Performance Report. |

|

4.47 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should put into effect a completed IT Strategic Plan for the Government of Canada. (4.16–4.23, 4.43–4.46) |

The Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will complete the IT Strategic Plan for the Government of Canada by 31 March 2016, and will work with departments and agencies to help them implement the plan once it is approved. |

|

4.63 In order for partners to comply with government IT security policies, guidelines, and standards, Shared Services Canada should establish expectations and provide the necessary information to partners for the IT infrastructure and services that it manages. (4.48–4.62) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. To help partners carry out their IT security responsibilities, Shared Services Canada will

|

|

4.74 Shared Services Canada should reassess the reporting process for its transformation initiatives to

|

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada (SSC) will further develop its benefits management framework to align to the key benefits stated when SSC was created and to include methods for measuring progress. In addition, SSC will review and confirm its key performance indicators to assure the accuracy of the progress against the Transformation Plan. The benefits management framework will be completed by December 2016. SSC will improve its reporting and review mechanisms to ensure that the information on progress against transformation initiatives is reliable, clear, and meets the needs of its internal oversight bodies. This will be completed by December 2016. |

|

4.85 In supporting its funding strategy for its ongoing operations and investments, Shared Services Canada should include in its strategy

|

The Department’s response. Agreed. To support an update to the Transformation Plan in fall 2016, Shared Services Canada (SSC) will document the methodology it uses to allocate funding for its investment in legacy and transformation initiatives, including its prioritization methodology, detailed criteria, and rationale. SSC’s Service Pricing Strategy will align the funding strategy to the Government of Canada’s service requirements. SSC formed a Chief Information Officer–Director General Pricing Strategy Committee in April 2015 to assist in the development of pricing strategies for SSC services. Mobile devices and email service pricing strategies were approved in June 2015 and are currently being implemented. Pricing strategies for the remaining 20 services will be approved by December 2016. The Service Pricing Strategy will be reviewed annually by SSC senior management as part of the planning cycle. |

|

4.98 Shared Services Canada should periodically refine its methodologies and practices to enable it to accurately determine and report savings. (4.75–4.80, 4.86–4.97) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada will refine its methodologies and practices for determining savings to support an update to the Transformation Plan in fall 2016. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: