2017 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Audit ReportReport 4—Mental Health Support for Members—Royal Canadian Mounted Police

2017 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 4—Mental Health Support for Members—Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Independent Audit Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Meeting members’ mental health needs

- The Royal Canadian Mounted PoliceRCMP did not adequately fund new programs for early detection and intervention, and implementation was delayed and inconsistent

- The RCMP’s health services offices did not facilitate timely access to mental health treatment for all members or provide services consistently

- The RCMP did not effectively support its members on off-duty sick leave or adequately accommodate their return to work

- Monitoring and improving mental health support

- Meeting members’ mental health needs

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibit:

Introduction

Background

4.1 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is Canada’s national police service, and its mandate and operations are governed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act. RCMP employees are located in every region of Canada—urban, rural, and remote—and in 26 locations around the world. Federal policing is carried out in every province and territory in Canada. The RCMP also provides police services to the 3 territories, 8 provinces, more than 150 municipalities, more than 600 Indigenous communities, and 3 international airports. The organization has more than 29,000 employees (regular and civilian members, and public servants) located in 15 divisions, plus its national headquarters in Ottawa.

Operational stress injury—Any persistent psychological difficulty that results from operational duties and causes impaired functioning. Included are diagnosed medical conditions such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, panic attacks, and less severe conditions.

4.2 As a federal organization, the RCMP must establish and maintain effective occupational health and safety programs that are consistent with Treasury Board policies, standards, and procedures. It is responsible for providing a healthy and safe workplace and reducing the incidence of occupational injuries and illnesses. In fulfilling these responsibilities, the RCMP provides programs and services designed to support members’ mental health. For example, it requires that members in high-risk postings undergo mandatory health assessments, and it sometimes offers debriefings to affected employees after a critical incident. In addition, the federal government’s Employee Assistance Program services are available to all public service employees, including RCMP members. However, these services are short-term and are not specifically designed to address the complex needs of RCMP members, such as those with operational stress injuries.

4.3 In May 2014, the RCMP took the important step of introducing its five-year Mental Health Strategy to contribute to a psychologically healthy and safe workplace, and to provide greater support to its employees. The strategy defined mental health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her own community.”

4.4 The goals of the strategy are

- to take proactive steps to help employees maintain or improve psychological health,

- to eliminate the stigma associated with psychological health problems within the RCMP, and

- to continually improve the management and review of programs and services that support psychological health and safety.

4.5 The strategy also identified five key areas to better manage mental health within the workplace:

- promotion,

- education,

- prevention,

- early detection and intervention, and

- continuous improvement.

4.6 Health services offices. The health services office in each RCMP division is responsible for facilitating access to external psychological and physical health treatment providers for RCMP members who need them. It does not directly provide mental health treatment to members. Some smaller or more remote divisions may share the same health services office with another division. For example, members in Yukon are served by the health services office in Surrey, British Columbia.

4.7 Health services offices are staffed by

- health services officers (medical doctors),

- divisional psychologists,

- nurses,

- return-to-work facilitators,

- duty-to-accommodate coordinators, and

- administrative support staff.

Health services staff work closely with members and their supervisors, using a team-based approach to manage the medical files.

4.8 Regular members can access the services of health services offices whether or not their condition is work-related, but civilian members are eligible for assistance only for work-related conditions. For non-work-related conditions, civilian members have access to the same health services as used by other federal public service employees. Under the Canada Health Act, all residents of a province or territory are entitled to receive health services, including mental health care, under the terms of their provincial or territorial health care plans.

4.9 Health services officers or divisional psychologists, or both, are responsible for

Off-duty sick leave—As used in this report, an absence of more than 30 days due to illness.

- recommending to the commanding officer or delegate for occupational health and safety services whether members’ conditions are work-related,

- recommending or referring members to external treatment providers,

- reviewing treatment plans and recommending their approval,

- reviewing and revising fitness-for-duty assessments, and

- recommending whether members on off-duty sick leave are ready to return to work or should consider taking a medical discharge.

4.10 Although the RCMP does not provide treatment to members directly, the health services officer has the authority to pre-authorize medical treatment and services and can recommend the approval, rejection, or revision of a treatment plan. For example, officers may reject or revise treatment plans if they believe that the proposed treatments are controversial or not evidence-based, and are not covered under the RCMP’s Health Care Entitlements and Benefits Program.

4.11 Veterans Affairs Canada. The RCMP has partnered with Veterans Affairs Canada to provide members, retirees, and their families with access to more complex mental health programs and services than those available through the publicly funded health care system. Veterans Affairs Canada has developed partnerships with the provinces to establish specialized assessment and treatment services for operational stress injuries, including post-traumatic stress disorder. These clinics are funded by Veterans Affairs Canada but are managed and operated by the provincial health authorities. Once RCMP members are referred, they can receive services from operational stress injury clinics. Veterans Affairs Canada has agreements for 11 outpatient clinics in eight provinces and for 1 in-patient clinic offering long-term residential treatment. The RCMP covers the costs of these services.

Focus of the audit

4.12 This audit focused on whether RCMP members had access to mental health support that met their needs. We examined selected mental health programs and services that supported the following two key areas of the RCMP’s 2014–2019 Mental Health Strategy:

- early detection and intervention, and

- continuous improvement.

4.13 Specifically, we examined the delivery of the following programs, services, and activities:

- Road to Mental Readiness program;

- Peer-to-Peer program;

- Periodic Health Assessments;

- health services offices (intake and assessment, recommendation or referral to external treatment providers, review and approval of treatment plans, fitness-for-duty assessments);

- Health Care Entitlements and Benefits Program (external treatment, including operational stress injury clinics); and

- disability case management (medical leave, return to work, and medical discharge).

4.14 In conducting this audit, we used representative sampling to review medical case files of RCMP members to assess whether they had access to support that met their mental health needs. We also surveyed active RCMP members and members on off-duty sick leave.

4.15 This audit is important because poor mental health has a direct impact on the well-being of members, their colleagues, and their families. Left unmanaged and unsupported, mental health issues can lead to increased absenteeism, workplace conflict, high turnover, low productivity, and increased use of disability and health benefits. Ultimately, members’ poor mental health affects the RCMP’s capacity to serve and protect Canadians.

4.16 We did not examine progress against the other key areas of the RCMP Mental Health Strategy—promotion, education, and prevention—and we did not audit the overall success of the RCMP Mental Health Strategy. We therefore did not examine whether the RCMP proactively protects members from the impacts of psychological risks through its programs that support these key areas. Finally, we did not directly examine the causes of members’ mental health conditions.

4.17 Rather, our examination began at the point a member self-identified, or was identified by another party (for example, a supervisor or colleague), as having a mental health condition, and it ended with the member’s case outcome.

4.18 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Meeting members’ mental health needs

Overall message

4.19 Overall, we found that the RCMP did not adequately meet its members’ mental health needs. The RCMP was one of the first federal government organizations to introduce a mental health strategy. However, it did not make the strategy’s implementation a priority or commit the human and financial resources needed for the strategy’s full and effective implementation. We found that new mental health programs to support early detection and intervention were only partially implemented, and that the RCMP did not allocate budgets to support them. We also found that while 57 percent of members received easy and timely access to the mental health support they needed, one in six members (16 percent) did not. For 27 percent of cases examined, the RCMP did not have records that would allow us to assess whether members received the help they needed when they needed it. Finally, we found that members’ supervisors and health services staff did not fulfill their roles in supporting members who were returning to work from mental health sick leave. One in five members who sought mental health support from a health services office did not return to work or was discharged.

4.20 These findings matter because the RCMP is only as strong as its members. If the organization does not effectively manage members’ mental health and fulfill its responsibilities to support their return to work, members struggle to carry out their duties, their confidence in the RCMP may be undermined, and the RCMP’s effectiveness may be reduced.

4.21 To fulfill its mandate of serving and protecting Canadians, the RCMP must ensure that its members are fit for duty. While the organization also expects members to maintain their own health and fitness for duty, the goal of its Mental Health Strategy is to detect mental health conditions at an early stage and intervene before the conditions become so unmanageable that members cannot perform their duties. In some cases, members must discontinue regular duties to receive treatment. After members receive treatment and are reassessed as fit for duty, the RCMP is responsible for accommodating their needs when they return to work.

4.22 To support members’ successful recovery and reintegration into the workplace, the RCMP uses a team approach. Health services staff are primarily responsible for supporting members’ occupational health, along with

- evaluating members’ medical needs and fitness for duty;

- reviewing the availability and use of appropriate medical treatment;

- evaluating the physical, psychological, and medical factors that may impede members’ successful recovery and reintegration into the workplace;

- working with members and their supervisors to provide support while members are on leave, and once they are ready to return to work;

- documenting case management activities; and

- protecting the confidentiality of members’ case information.

4.23 To accommodate RCMP members returning to work after off-duty sick leave, the members’ commander or supervisor is primarily responsible for

- maintaining open communication with members,

- ensuring that all absences due to illness or injury are reported within the required leave system,

- referring members’ cases to return-to-work facilitators or disability case managers,

- identifying opportunities for accommodation within the workplace, and

- participating in accommodation plans.

4.24 The RCMP Mental Health Strategy states that in the early stages of mental distress or mild dysfunction, people can cope when they are adequately supported. They are more likely to improve their mental health when they receive professional help from health care providers, or coaching from peers. Quick access to the proper services is critical to ensure that RCMP members can continue to perform their duties. In addition, the RCMP Mental Health Strategy states that a supervisor’s response when a mental health condition is detected is a key factor in early intervention, and therefore in a member’s timely access to mental health programs and services.

4.25 Once members have accessed mental health services, the process cannot stop there. For disability case management to be effective, health services offices need to be adequately resourced. Members need information, monitoring, and support to recover and return to work as soon as possible. Health services staff and members’ supervisors must understand and fulfill their roles and responsibilities as part of the case management team.

4.26 In September 2016, the RCMP estimated that about 900 regular and civilian members were on sick leave. We asked RCMP officials how many of the approximately 900 members were on sick leave for mental health reasons. They could not provide an answer because the organization did not collect and report this information. The officials explained that obtaining this information would have required a manual review of paper files for all cases.

The RCMP did not adequately fund new programs for early detection and intervention, and implementation was delayed and inconsistent

4.27 We found that new programs designed to contribute to early detection and intervention were not consistently implemented across divisions. The RCMP took the important step of introducing a mental health strategy, but it did not develop a business plan or provide sufficient funding and human resources to support the new programs. Staff members assigned to the implementation did so in addition to their regular duties, which limited their ability to support these new mental health initiatives. As a result, implementation was delayed. In addition, supervisors did not always take the required actions to intervene when informed of issues affecting members’ work performance or wellness. We found that supervisors required additional training on their roles and responsibilities for providing support to members.

4.28 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Implementation of new mental health programs

- Resourcing of new mental health programs

- Support from supervisors

4.29 This finding matters because one of the goals of the RCMP Mental Health Strategy is to detect mental health conditions at an early stage and intervene when

- the conditions are still manageable, and

- members can still perform their regular duties.

If support is not provided early on, members who seek help may not be able to continue working or to return to their regular duties. As long as a member is on off-duty sick leave, the vacant position cannot be filled. The number of members on off-duty sick leave represents a capability gap in delivering on the RCMP’s mandate.

4.30 If members perceive that others who seek support are unable to continue performing their regular duties, they may believe that their own careers will be negatively affected if they seek help for mental health conditions. As a result, members may attempt to hide their mental health conditions, which could adversely affect the RCMP’s organizational capacity to fulfill its mandate and could ultimately compromise the safety of RCMP members and the Canadians they are there to protect.

4.31 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.43.

4.32 What we examined. We examined whether selected new programs that were designed to contribute to early detection and intervention were implemented as intended across divisions.

4.33 We also surveyed 22,237 regular and civilian RCMP members on active duty across Canada. We received 6,769 responses, for a 30 percent response rate. We surveyed an additional 828 members on off-duty sick leave and received 261 completed surveys, for a response rate of 31 percent.

4.34 Implementation of new mental health programs. In May 2014, the RCMP introduced its Mental Health Strategy, which was intended to improve the management of mental health in the workplace. In particular, the strategy was aimed at proactively helping employees maintain or improve mental health, eliminating stigma, and continually improving the management of mental health programs. As part of the strategy’s rollout, the RCMP introduced the following initiatives designed to contribute to early detection and intervention:

- Road to Mental Readiness program, and

- Peer-to-Peer program.

Although we did not examine progress against the other key areas of the RCMP Mental Health Strategy—promotion, education, and prevention—we acknowledge the organization’s efforts in these areas.

4.35 The Road to Mental Readiness program was introduced in 2014 as mandatory training for all supervisors and employees. The training was designed to help supervisors identify and respond to employees’ mental health conditions. The Peer-to-Peer program, introduced in the same year, involved assigning members as coordinators to recruit and train volunteer advisers, who would provide “listening support” and information about services available to fellow employees. These advisers would not assess, counsel, or refer members for treatment. We found that the RCMP did not sufficiently resource these initiatives and did not consistently or completely implement them across all divisions.

4.36 We found that the Road to Mental Readiness program was only partially implemented despite being mandatory, and that staff ran the workshops while performing their full-time duties. The RCMP intended to have this training completed by April 2017. However, at the time of the audit, we found that the RCMP had still not trained all the trainers, and that just over one third of employees had received the training.

4.37 We also found that the RCMP did not provide sufficient resources for the Peer-to-Peer program. As a result, some divisions had made progress with recruiting volunteer advisers, but others had not recruited any advisers.

4.38 Resourcing of new mental health programs. We found that the RCMP did not put a business plan in place or allocate resources to support its new Mental Health Strategy. We asked the RCMP to provide information on how the mental health programs and services were resourced. Officials told us that they could not confirm how much was spent because the RCMP did not use detailed line items to track spending. Also, because staff delivered the Road to Mental Readiness and Peer-to-Peer programs as part of their full-time duties, the RCMP did not track the cost.

4.39 We also found that health services offices in all divisions were under-resourced. They lacked the capacity to ensure that each member’s case was well managed and that all members received the support they needed. For example, a 2015 program review in one of the largest divisions identified a significant capacity gap in health services offices that was affecting service delivery. Yet the RCMP did not provide funding or increase capacity in the division to address the gap.

4.40 In addition, staffing shortages in three health services offices created backlogs in reviewing hundreds of Periodic Health Assessments. The RCMP conducts these assessments every one to three years to monitor each member’s fitness for duty. By helping to identify mental health conditions, the assessments serve as an early detection tool. The backlogs represented a risk that the RCMP would not intervene until a health services officer reviewed the form. There was also a risk that some members would not proceed with new assignments, mental health treatment, or a return to work because of the delays in reviewing the assessments.

4.41 We found that the RCMP’s lack of resources—combined with the high demand for services, the backlogs, and frustrated members—created a stressful workplace for health services staff. Moreover, health services offices found it difficult to attract and retain qualified medical and mental health practitioners.

4.42 In 2015, the RCMP reassigned health services staff across all divisions to review psychological assessments of RCMP recruit applicants. Already under-resourced, the staff had even less time to manage members’ case files and support members’ mental health needs. In December 2016, the RCMP informed us that it was in the process of outsourcing the review work so that health services staff could return to managing members’ cases.

4.43 Recommendation. The RCMP should support the full implementation of the programs and services that support its 2014–2019 Mental Health Strategy by preparing a business plan to guide the final two years of implementation.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. When the RCMP Mental Health Strategy was introduced in 2014, it included a requirement for the preparation, on an annual basis, of a Mental Health Strategy Action Plan. The purpose of the action plan is to identify the components of the strategy that will receive particular attention each year, to identify the specific activities that will be undertaken to address them, and to indicate their target completion dates. As the annual action plan does not include resource requirements, the RCMP will transform it into a business plan designed specifically to guide implementation efforts for the final two years of the strategy. This business plan will clearly articulate resource requirements, highlight specific areas of priority, convey any risks to the full implementation of the strategy, and indicate the strategies that will be employed to mitigate risks. The business plan will be developed by June 2017.

4.44 Support from supervisors. We found that supervisors did not always take the required actions to intervene when informed of issues affecting members’ work performance or wellness. During the course of our audit, the RCMP informed us that it had introduced the National Early Intervention Program in January 2016. The program includes a system that identifies issues that may be affecting the work performance or wellness of active RCMP members, which supports the goal of intervening as early as possible. The system scans records of incidents such as conduct allegations, public complaints, police motor vehicle collisions, and harassment allegations. It produces a notification if a pattern of three or more incidents in 12 months emerges. Program officials then contact the member’s division to inform them that a non-disciplinary intervention is required.

4.45 Although the program was still in the early stages of implementation, the RCMP produced a progress summary in October 2016. The summary stated that many supervisors did not act when notified that interventions with members were required. Supervisors held the required face-to-face meetings with only 199 of 349 members identified (57 percent). The summary also found that supervisors closed employee cases too quickly, without speaking to the members, and provided invalid reasons for doing so. It suggested that more effort was needed to educate supervisors on their roles and responsibilities.

4.46 The purpose of the National Early Intervention Program is undermined if supervisors do not take the required action when informed of issues that may be affecting members’ work performance or wellness. More important, the goal of the RCMP Mental Health Strategy to detect issues and intervene early is not supported, and the opportunity to provide support to members who may be in need is missed.

4.47 This lack of support from supervisors at the early detection and intervention stage suggests that more work needs to be done to educate leaders about mental health and about their roles and responsibilities in supporting members. The Road to Mental Readiness program was designed to provide this training, but it was not fully implemented.

The RCMP’s health services offices did not facilitate timely access to mental health treatment for all members or provide services consistently

4.48 We found that the RCMP’s health services offices facilitated timely access to external mental health treatment for many members who needed it (57 percent), but they did not meet the needs of all members. In 16 percent of cases, members did not receive timely access. For the remaining 27 percent of cases, health services staff failed to document the required case management information, so we could not determine whether those members received the mental health support they needed when they needed it.

4.49 We also found that mental health service delivery was inconsistent across all divisional health services offices. Members’ access to treatment and the nature of their treatment varied, depending on the divisions to which they were assigned. In our survey of members, more than half of respondents on off-duty sick leave and one quarter of active respondents raised concerns about having easy and timely access to the mental health programs and services they needed.

4.50 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

4.51 This finding matters because RCMP members need to feel supported by their organization. They need easy and timely access to mental health treatment to reduce the risk that they will not be able to perform their regular duties, and to reduce the amount of time they are away from work. Leave is costly to the RCMP, both financially and in terms of reduced organizational capacity to deliver services to Canadians.

4.52 Members need to know that regardless of the division they are posted to, they can access the mental health support they need. Members also need to know that RCMP officials apply the required policies and procedures consistently. Otherwise, inconsistent application presents a risk that members in one division may receive timely support, enabling them to return to work, while members in another division may not receive timely support, ultimately hindering their ability to return to work.

4.53 It is important for the RCMP to track and document whether members are receiving timely access to the mental health treatment they need. This information is necessary for evaluating whether the member has been given the support they need to recover and return to work. It is also important for planning for continuous improvement in managing members’ mental health. The failure to document how an RCMP member’s case is managed poses risks to the organization in terms of occupational health, legal requirements, and employee relations.

4.54 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.74.

4.55 What we examined. We examined whether RCMP members on active duty and off-duty sick leave had easy and timely access to the mental health programs and services they needed. Specifically, we examined whether the staff at health services offices facilitated members’ access to the mental health treatment they needed without unreasonable delays. This would include providing members with information on available programs and services, people to contact, and ways to navigate the process. We also examined whether health services offices delivered services consistently and followed the required policies and procedures.

4.56 Access to external mental health treatment. We reviewed whether the RCMP’s health services offices had applied consistent policies and procedures, including service standards. We then used random representative sampling to review 51 medical case files—from 46 regular members and 5 civilian members—to help us determine whether the members received easy and timely access to the mental health services they needed. We also examined relevant information contained in electronic case management systems.

4.57 We found that the RCMP’s health services offices had no service standards in place for mental health services. As a result, staff did not know what guidelines to follow when providing services, and members had no formal way to measure whether they were receiving reasonable access to services.

4.58 Of the 51 member files we reviewed, we found that 29 members (57 percent) had easy and timely access to mental health treatment. In one case, for example, a member met with health services staff within one day of requesting a meeting, was provided with a list of mental health practitioners, and made contact with a third-party mental health practitioner within one week. In another case, a member requested mental health support and was referred to a mental health practitioner within one week. We also found three cases in which members’ requests for additional treatment were approved within one week. Although service standards were absent, these response times were reasonable, in our view.

4.59 The results of our case file review show that despite the lack of resources, health services staff made many members aware of the programs and services available to them, and they facilitated easy and timely access to mental health treatment.

4.60 However, not all members’ needs were met. In eight cases (16 percent), members experienced delays in receiving initial assessments and approvals for treatment from health services offices, or delays in ongoing treatment. These delays prevented members from having easy and timely access to mental health treatment. For example, in a Periodic Health Assessment, a member identified the need for mental health treatment, but the file showed no evidence that health services staff responded to this need. The member was not seen by a mental health practitioner until six months later. In the same case, delays in approvals of additional treatments ranged from one to three months. In two other cases, treatment of members with mental conditions was delayed for well over one year.

4.61 In 14 cases (27 percent), we could not assess whether members had easy and timely access to mental health services because their files contained little to no information. For example, the following information should have been documented:

- how and when the member was identified for treatment,

- when requests and approvals for treatment were made, and

- how and when the member accessed treatment.

According to RCMP policies, this information must be documented, but it did not exist in any of the required information systems. As a result, we could not assess whether members received the help they needed when they needed it.

4.62 Our case file review showed that although many members received easy and timely access, one in six (16 percent) did not, and 27 percent of cases could not be assessed. Our survey of active RCMP members and members on off-duty sick leave showed that respondents had concerns about easy and timely access.

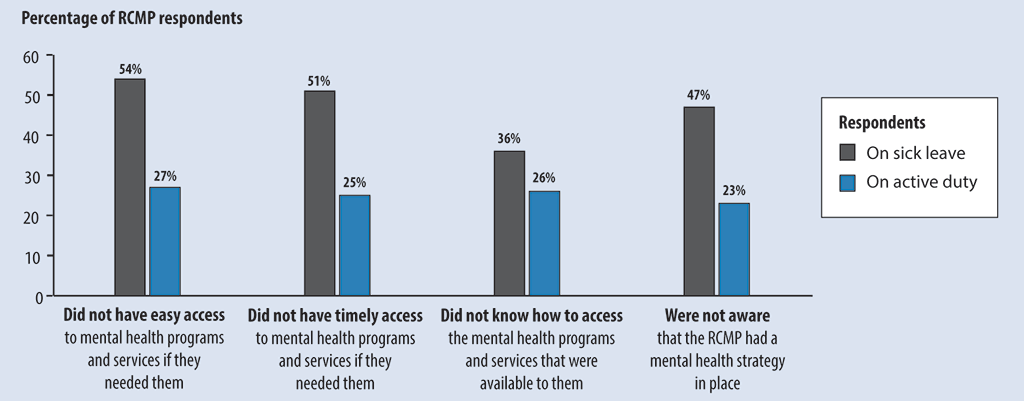

4.63 According to our survey results, 54 percent of respondents on off-duty sick leave reported that they did not have easy access to mental health programs and services if they needed them. Similarly, 51 percent of respondents who were on off-duty sick leave and 25 percent who were still actively working reported that they did not have timely access to mental health programs and services if they needed them. In our view, the RCMP’s inconsistent implementation of its new mental health programs may be feeding this perception and overshadowing more positive experiences (Exhibit 4.1).

Exhibit 4.1—Some survey respondents reported that they did not have easy or timely access to the RCMP’s mental health services or did not know how to access these services

Source: Data from a survey of RCMP members on active duty and off-duty sick leave, conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. For details about the survey, see About the Audit at the end of this report.

Exhibit 4.1—text version

This graph shows results from a survey of RCMP members on off-duty sick leave and active duty regarding the organization’s mental health programs and services.

| Survey finding | Percentage of respondents on sick leave | Percentage of respondents on active duty |

|---|---|---|

| Did not have easy access to mental health programs and services if they needed them | 54% | 27% |

| Did not have timely access to mental health programs and services if they needed them | 51% | 25% |

| Did not know how to access the mental health programs and services that were available to them | 36% | 26% |

| Were not aware that the RCMP had a mental health strategy in place | 47% | 23% |

Source: Data from a survey of RCMP members on active duty and off-duty sick leave, conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. For details about the survey, see About the Audit at the end of this report.

4.64 Consistency of service delivery. The RCMP does not provide treatment, but it recommends or refers members to external treatment providers. According to the RCMP Health Services Manual, health services offices are responsible for preparing and annually updating lists of treatment providers. They are not required to publish the lists. We asked each health services office to provide its list and to describe the process it used to compile and share the list with members. Five divisions produced lists, but they provided few details on the process used to add or remove providers, or on how they shared the lists with their members. The remaining five divisions explained that they did not prepare lists of treatment providers. In some cases, members were able to select the treatment provider of their choice. This lack of consistency and transparency meant that there was no easy way for all members to know which treatment providers were available, whether the health services office recommended them, and why the providers were or were not recommended.

4.65 Under RCMP policy, the health services officer is responsible for reviewing and revising fitness-for-duty assessments, and for recommending whether a member is ready to return to work. The health services officer can recommend the revision or rejection of a treatment plan because the plan is controversial or not evidence-based, and is not covered under the RCMP’s Health Care Entitlements and Benefits Program.

4.66 We found contrasting approaches to the application of the policy. In one division, external provider treatment plans were regularly rejected for the specific reason of returning members from off-duty sick leave to work as quickly as possible. As a result, the number of members on leave fell by more than half between November 2015 and May 2016, from 61 to 27. Of the 34 members who were no longer on leave, approximately half returned to work in some capacity, and the other half took a medical discharge from the RCMP.

4.67 In another division, we found a different approach to applying the policy and returning members to work—one that focused on a model of trust and support. For example, some members on off-duty sick leave were given the option of pairing with another member while gradually returning to full operational duties. The approach was designed to reduce the number of members on off-duty sick leave, but doing so over the long term while meeting members’ mental health needs.

4.68 We asked the divisions whether they monitored these members’ outcomes to know whether their approaches met members’ mental health needs. The divisions responded that they did not yet have a process in place to systematically collect, monitor, and report on results.

4.69 This inconsistency in approaches between divisions, together with the absence of information demonstrating that the approaches meet members’ mental health needs, may undermine members’ confidence in the organization.

4.70 We also found inconsistencies in referrals to Veterans Affairs Canada’s operational stress injury clinics. In our case file review, 33 members were identified as having operational stress injuries, such as post-traumatic stress disorder. We found that only 12 of these members (36 percent) were referred to an operational stress injury clinic, and that some divisions referred almost all members while other divisions did not refer any.

4.71 In our interviews with health services staff and with officials at Veterans Affairs Canada’s operational stress injury clinics, we learned that a referral for an operational stress injury depended on various factors, such as the external provider’s availability and ability to treat the member. Officials also told us that referrals could depend on whether staff at the health services office and the officials at the operational stress injury clinic had a positive working relationship.

4.72 In addition, we found that rural and remote members had inconsistent access to mental health services, depending on where they were located. Officials at two of Veterans Affairs Canada’s operational stress injury clinics said that the clinics were working on improving access to mental health services for rural and remote members by using technologies such as telemental health services delivered through videoconferencing. RCMP health services staff told us that members could be transported to an urban centre for treatment, if necessary.

4.73 Finally, we found inconsistencies in how the RCMP’s health services offices interpreted fitness for duty. To meet the requirement in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act of ensuring that each member is fit for duty, health services officers must assess whether each member can perform operational duties such as possessing a firearm, driving a vehicle, and participating on specialized enforcement teams. The interpretation of fitness for duty is recorded in the member’s medical profile, which includes a numerical rating. The medical profile is then used to determine whether the member meets the minimum medical requirements of a particular position and can therefore perform the duties of the position. We found that the RCMP lacked clear guidelines to support these interpretations. This lack of clarity created a risk that a member could be assessed as fit for duty in one division, but assessed as unfit in another. Therefore, how fitness for duty is interpreted could have significant consequences for the member’s career path.

4.74 Recommendation. The RCMP should ensure that all health services staff apply policies and procedures consistently. The RCMP should also consider adopting

- national standards for health services delivery, and

- best practices from across divisions and from other organizations.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The RCMP National Policy Centre will improve communication with health services staff across all divisions to ensure the consistent interpretation and application of policies and procedures. Health professionals throughout the RCMP will continue to hold regular meetings within their respective communities of practice (for example, psychologists or nurses) to discuss the day-to-day implementation of policies and procedures. In addition, in order to develop national standards and identify best practices, a working group will be established with representation from within each health services community of practice to analyze the work activity, level of effort, and associated resource requirements. This will better position the RCMP to articulate national standards for health services delivery. The working group will be created by June 2017, with a goal of establishing national standards and identifying best practices by December 2017.

The RCMP did not effectively support its members on off-duty sick leave or adequately accommodate their return to work

4.75 We found that one in five RCMP members who sought support for a mental health condition through health services offices did not return to work. In other words, if this finding is applied to the RCMP as a whole, members who take off-duty sick leave for mental health reasons have a 20 percent chance of remaining on sick leave or being discharged from the RCMP.

4.76 We found that health services staff and supervisors responsible for disability case management, including return-to-work accommodation, did not consistently fulfill their roles and responsibilities to meet members’ needs. We found that inadequate oversight of cases, poor communication with members, and incomplete information in case files prevented the RCMP from providing effective support to members on off-duty sick leave who were receiving mental health services. We also found that supervisors did not always accommodate members’ return to work as required.

4.77 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

4.78 This finding matters because the RCMP is responsible for supporting members’ successful recovery and reintegration into the workplace. If the RCMP does not support its members while they are on off-duty sick leave and when they are ready to return to work, the members’ careers and the RCMP’s organizational capacity could be negatively affected. Moreover, the longer members remain on sick leave, the more difficult their rehabilitation and reintegration into the workforce. Poor disability case management is costly to the organization and can have a detrimental effect on the well-being of members who cannot return to work. The lack of effective support could add to members’ stress, reduce their confidence in the organization, and exacerbate their mental health conditions.

4.79 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 4.89 and 4.96.

4.80 What we examined. We examined whether RCMP health services staff and supervisors met members’ needs by effectively fulfilling their responsibilities when members took off-duty sick leave for mental health reasons. These responsibilities involve effective disability case management and return-to-work accommodation.

4.81 We also assessed whether members who received mental health support through health services offices could continue their work or return to regular duties. In addition, we looked at whether their condition became unmanageable to the point that they could not perform their duties. To examine these matters, we used random representative sampling to review 51 RCMP medical case files from 46 regular members and 5 civilian members.

4.82 Disability case management. RCMP documents state that as part of their disability case management responsibilities, supervisors and health services staff must keep in regular contact with members on off-duty sick leave. They must also provide a summary of contact with these members for entry into an RCMP national database. However, the documents do not define “regular contact.” RCMP internal reports demonstrate that the organization was aware that supervisors were not contacting members on off-duty sick leave until well after 30 days “in most cases.” The RCMP reported that in many cases, five or six months had elapsed before there was any contact between the RCMP and members.

4.83 In our case file review of 51 members, we found that 24 members who sought mental health support continued to work in some capacity (16 on regular duties and 8 on restricted or administrative duties). In 2 cases, members’ operational status could not be determined. In 25 cases, members required one or more periods of off-duty sick leave. Regular contact of members on off-duty sick leave by supervisors was documented in only 3 of these cases. The other 22 cases (88 percent) showed little to no evidence of supervisor involvement or support.

4.84 We found that most divisions could not produce an accurate list of members on off-duty sick leave and their contact information. Supervisors are required to maintain contact with the members and ensure that contact information is updated. In our view, the RCMP cannot support members on off-duty sick leave if supervisors do not have the access to the information they need to contact these members at least once every 30 days.

4.85 A 2014 internal audit of RCMP members’ long-term sick leave revealed similar problems:

- Commanders’ knowledge and awareness of their roles and responsibilities were not sufficient to ensure the accurate and timely recording of long-term sick leave.

- Monitoring and oversight activities were not sufficient to ensure that long-term sick leave was managed appropriately.

4.86 In response, RCMP management acknowledged the need to improve the organization’s disability management and stated that “concrete actions” were being taken to address the problems. We found that the RCMP did not approve funding for a new disability case management program until almost two years after the 2014 internal audit.

4.87 The new program was to be implemented by the end of December 2016. At the time of our audit, the RCMP was still establishing the program, and a number of deadlines had been missed. For example, the RCMP planned to hire and train 30 new disability management program staff by 1 November 2016. The role of the new staff was to proactively work with members, supervisors, and health services to staff to coordinate support for early intervention and return to work. By 16 December 2016, the RCMP had hired and trained only 8 advisers.

4.88 It has become essential for the RCMP to take steps toward improving case management for members and improving the support of their mental health needs.

4.89 Recommendation. The RCMP should ensure that officials responsible for disability case management carry out this responsibility effectively. Specifically, the RCMP should ensure that

- all officials responsible for disability case management have a clear understanding of their roles and responsibilities, and that they fulfill them; and

- the required number of disability management advisers are hired and trained.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. Many of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s findings with respect to disability management mirror those identified by the RCMP through internal reviews and were highlighted in the business case developed for an enhanced disability management and accommodation program (approved by the Commissioner in February 2016). On 1 April 2017, the RCMP will publish a comprehensive policy that will clearly outline the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders within the disability management and accommodation program. The policy will be supported by a suite of guidelines and working tools designed to guide activities. The RCMP is also developing an online supervisor training course to help educate supervisors on their roles and obligations in supporting members in the area of disability management and accommodation.

A total of 25 disability management advisers and 11 disability management coordinators will be hired. As of 28 February 2017, 24 of the 25 disability management advisers and 7 of the 11 disability management coordinators will have been hired. An orientation and training program will be held the week of 28 February 2017 to familiarize disability management advisers and disability management coordinators with the enhanced disability management and accommodation program. A primary focus of this training is on the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders in the disability management and accommodation process.

4.90 Return-to-work accommodation. For the 25 members in our case file review who took one or more periods of off-duty sick leave, we found problems with how health services staff and supervisors fulfilled their return-to-work accommodation responsibilities. These problems included the following:

- Members were not given the required information in a timely manner concerning their rights and responsibilities for accommodation and return to work.

- Supervisors did not facilitate members’ return-to-work accommodation, so the return to work was unnecessarily delayed.

- A member was on off-duty sick leave for over one year, but no effort was made to accommodate the return to work.

4.91 We also found that many members were reluctant to seek help for mental health conditions because they worried about the implications of doing so. From our survey of regular and civilian RCMP members, we found that 79 percent of respondents on off-duty sick leave and 44 percent of active duty respondents believed that seeking help would have a negative impact on their careers with the RCMP.

4.92 Of the 30 members we interviewed, 20 told us that the stigma surrounding mental health negatively affected their return to work. They believed that some supervisors and colleagues saw coming forward with a mental health concern as a sign of weakness. Members further explained that when they came forward, they felt that they were

- not believed and labelled “fakers,”

- subjected to reprisals from supervisors,

- subjected to discriminatory human resource practices when they returned to work, and

- socially isolated in the workplace.

4.93 According to both our case file review and interviews, these perceptions led members to believe that seeking mental health support through a health services office had negatively affected their careers. They reported that

- the organization did not care about them,

- they had not been offered meaningful work when they returned from sick leave, and

- the organization was encouraging them to accept a medical discharge.

4.94 Mental health is a complex matter, and it is neither reasonable nor desirable to expect that all members with mental health conditions will continue to work or return to regular operational duties. The RCMP Mental Health Strategy aims to reduce the risk that members with identified mental health conditions will be unable to perform their duties. However, it is our view that the RCMP could be doing much more to facilitate a member’s return to regular duties.

4.95 The Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet is assessing deputy ministers’ performance according to how well they have responded to the government’s priority of building a healthy and respectful workplace with an emphasis on mental health. The RCMP Commissioner is assessing the performance of his senior executives in a similar manner. However, this government priority is not yet part of the performance assessments of the RCMP’s managers and supervisors.

4.96 Recommendation. The RCMP should assess how well managers and supervisors support and respond to the mental health of their employees and should include these assessments in their performance reviews. For managers and supervisors who are eligible for performance pay, the RCMP should consider linking it to how well they have fulfilled their roles and responsibilities related to disability case management, return-to-work accommodation, and the support of members’ mental health more broadly.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. In recognition of the importance of mental health, a May 2016 directive from the Commissioner required that all executive performance agreements for the 2016–17 fiscal year include a commitment to “build a healthy and respectful workplace with an emphasis on mental health.”

While the majority of managers and supervisors within the RCMP are not eligible for performance pay, they are expected to uphold the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s competency of Integrity and Respect by implementing practices to advance an inclusive, healthy organization, respectful of the diversity of people and their skills, and free from harassment and discrimination. This encompasses giving consideration to the mental health of employees and supporting the disability case management process. Through annual performance management agreements, managers and supervisors will be assessed on how they fulfill their roles and responsibilities in support of mental health in the workplace, including how they support implementation of national programs and initiatives related to mental health. In accordance with the May 2016 directive from the Commissioner, executives will be evaluated on their commitment to “build a healthy and respectful workplace with an emphasis on mental health” for the 2016–17 fiscal year.

To better equip supervisors to meet their roles and responsibilities for disability case management, an online supervisor training course will be launched in spring 2017. This course emphasizes the role of supervisors in supporting members and includes effective communication practices, identifying early warning signs, understanding the accommodation process, and return-to-work planning.

Monitoring and improving mental health support

The RCMP did not measure whether programs and services to support its Mental Health Strategy were working as intended

Overall message

4.97 Overall, we found that the RCMP did not develop performance measures to evaluate its Mental Health Strategy and ensure that it was working as intended to support members’ needs. The organization did not have a quality assurance framework or monitor its activities to support continuous improvement. As a result, the RCMP did not systematically collect or report any information on the results of the programs and services designed to support the strategy.

4.98 These findings matter because the RCMP must know whether the programs and services in place are

- meeting members’ needs,

- providing value for money, and

- reducing the negative personal and organizational impacts of members’ poor mental health.

If the RCMP does not know the origin and extent of the mental health issues affecting its members, it cannot properly resource or continuously improve its programs and services in response to members’ needs. As a result, members risk developing more serious mental health issues, which are more difficult and costly to resolve. Ultimately, these issues can affect the RCMP’s capacity to protect and serve Canadians.

4.99 In addition, without systems and practices to measure, monitor, and report on performance, the RCMP does not know

- how many members have received mental health services;

- what type of treatment each member has received;

- the total cost of treatment;

- the outcomes (for example, whether members have returned to work, and in what capacity, or whether they have been discharged); and

- whether members’ needs have been met.

4.100 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

4.101 The purpose of monitoring performance and supporting continuous improvement is to identify a program’s strengths and weaknesses, and to ensure that effective actions remain in place while ineffective actions are flagged for improvement or eliminated altogether.

4.102 The RCMP made a commitment in its 2014–2019 Mental Health Strategy to measure and monitor results by following the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace. Although voluntary, the standard states that organizations should review their “approach to managing and promoting psychological health and safety in the workplace, to assess conformance with the requirements and recommendations in this Standard.” According to the standard, if no measurement system exists, the organization should put one in place.

4.103 The RCMP established a governance structure aimed at continually improving the management and review of psychological health and safety. The structure included national and divisional mental health champions, who were expected to meet quarterly to discuss and share best practices. This commitment was linked to the RCMP commitment to continually improve the management and review of psychological health and safety.

4.104 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 4.113, 4.118, and 4.123.

4.105 What we examined. We examined whether the RCMP had systems and practices in place to know whether the selected mental health programs and services were meeting members’ needs.

4.106 Performance measurement and monitoring. We found that the RCMP did not develop a performance measurement and monitoring framework to support its Mental Health Strategy, despite its commitment to do so. We also found that the RCMP

- could not report on the results of the programs and services put in place to support the strategy,

- had no reliable baseline information to understand the prevalence of mental health issues in the organization or the nature of members’ mental health needs, and

- did not collect and review performance information.

4.107 We found that for each year covered by its Mental Health Strategy, the RCMP produced an action plan designed for reporting its progress in meeting the strategy’s goals. The RCMP’s 2015–2016 action plan presented some performance indicators and targets for each of the strategy’s three goals. However, it did not include measures to report on results. In the 2016–2017 action plan, the previous year’s performance indicators were omitted, and as before, the plan provided little or no information on results. The plans did contain information on planned or completed activities.

4.108 We also found that RCMP divisions had no frameworks or systems in place to measure the success of their mental health programs and services. Any gathering of baseline information (such as information collected from members through a survey), performance measurement, monitoring, or reporting was ad hoc, and the approach was inconsistent across divisions. The following are examples of these activities:

- In 2015, one large division conducted a review of its health services systems and practices to identify deficiencies and potential areas for improvement. The review found that health services staff reported high levels of frustration with both workload and reduced resource levels. Members reported frustration with time delays in requests for service. The review produced 41 recommendations. The division prepared an action plan and update in July 2016.

- In 2013 and 2014, a smaller division conducted an employee survey that assessed morale across detachments. Officials also consulted with members about their perceptions of the quality of the mental health services they had received. The division prepared action plans to address the problems.

4.109 Despite the efforts of individual divisions, the RCMP as a whole could not track, measure, or report on changes in members’ mental health, or assess the impact of the programs and services designed to support its Mental Health Strategy.

4.110 Moreover, we found that the national and divisional mental health champions did not meet quarterly as planned, despite their role in continually improving the management and review of psychological health and safety for the RCMP.

4.111 We found that Veterans Affairs Canada had good practices in place to track and report on wait times for provincially operated and managed operational stress injury clinics and on timeliness of intervention in quarterly and roll-up reports. The reports included performance measurement indicators to monitor how clients were managed. These indicators provided information on

- business days from referral to first contact (the target was 80 percent within 15 days),

- business days from referral to assessment (the target was 80 percent within 30 business days),

- business days from referral to first treatment session (the target was 80 percent within 30 business days),

- business days from referral to first session with psychiatrist (the target was 80 percent within 60 business days), and

- percentage of time spent in direct clinical contact.

4.112 The reports showed that operational stress injury clinics failed to meet some of the service standards that had been established. In our view, there is a risk that clients with an operational stress injury such as post-traumatic stress disorder did not always receive the mental health services they needed in a timely manner.

4.113 Recommendation. The RCMP should develop and implement a performance measurement and monitoring framework in a timely manner to know whether it is achieving the Mental Health Strategy’s objectives. The framework should include performance indicators and specify responsibilities for collecting, maintaining, analyzing, and reporting on performance information that is of good quality. The information should be used to continuously improve and plan for future mental health programs and services. These actions would better position the RCMP to address members’ mental health needs.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. Consistent with government requirements and expectations around results, the RCMP will establish a working group, made up of subject matter experts from health services, disability management and accommodation, and organizational health and well-being groups, with the specific purpose of developing and implementing a performance measurement and monitoring framework for its mental health programs and services. This framework will include performance measurement indicators and will specify responsibilities for the collection, maintenance, analysis, and reporting of qualitative and quantitative data. This information will be used to improve current, and to plan for future, mental health programs and services. The working group will be created in spring 2017, with a goal of establishing a performance measurement and monitoring framework by fall 2017.

4.114 Quality assurance. The RCMP’s Health Services Manual requires that divisional psychologists monitor the services delivered by external treatment providers on an annual basis. Specifically, they are required to maintain a current list of treatment providers by consulting members and providers. They are also required to ensure that treatment is effective by reviewing treatment providers’ reports. We found that these required tasks were not consistently done. In fact, most divisions reported that a quality assurance process was not in place.

4.115 Under a 2006 agreement of the Joint Network for Operational Stress Injuries Committee, the RCMP committed to collaborate with Veterans Affairs Canada to develop and monitor common indicators for quality management in the following areas: accessibility, acceptability, appropriateness, continuity, safety, and effectiveness. These indicators were to be used to assess the services provided by the operational stress injury clinics. We found that not all indicators existed.

4.116 We found that the Committee had not met since 2009, and that its regular work was not maintained. Instead, a limited number of meetings and communications between RCMP officials and officials of Veterans Affairs Canada’s operational stress injury clinics took place between 2009 and 2015 to discuss issues such as service fees and meeting RCMP members’ mental health needs. However, the two organizations did not exchange any information on the quality of the treatment services provided to RCMP members.

4.117 Monitoring quality assurance would allow the RCMP to ensure that external treatment providers’ interventions were monitored and recorded, and that when a problem arose, it could be addressed. A quality assurance process could include, for example, voluntary client satisfaction surveys. It could also ensure that complaints about the services received from treatment providers were tracked and analyzed. This validation of the quality of treatment providers’ services would help the RCMP ensure that members’ mental health needs were being met.

4.118 Recommendation. The RCMP should develop and implement a quality measurement and monitoring framework in a timely manner to measure whether the mental health services provided by treatment providers are meeting members’ needs. The framework should include client satisfaction surveys and quality management indicators. It should also specify responsibilities for collecting, maintaining, analyzing, and reporting on the indicators. The information should be used to continuously improve and plan for future mental health programs and services to help ensure that members’ mental health needs are addressed.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The working group established to develop and implement a performance measurement and monitoring framework for the RCMP’s mental health programs and services will also be used to create a quality measurement and reporting framework to measure whether the mental health services provided by treatment providers are meeting members’ needs. This framework, which will be incorporated into the larger performance measurement and monitoring framework for mental health programs and services, will specify responsibilities for the collection, maintenance, analysis, and reporting of both qualitative and quantitative indicators so as to ensure that all members’ mental health needs are addressed. The working group will be created in spring 2017, with a goal of establishing a quality measurement and reporting framework by fall 2017.

4.119 Case management information systems. We found that the RCMP did not have a case management information system to track members’ treatment, progress, and outcomes. This finding is important because the RCMP needs complete information on each member’s case to know

- how the member is progressing,

- whether supervisors and health services staff are fulfilling their roles and responsibilities, and

- whether the member has the required support to be fit for duty and able to return to work.

4.120 We found that information related to members’ case management was kept in multiple information systems that were not connected and did not communicate with one another. Members’ medical files were mainly paper-based, adding to the problem of maintaining complete and accurate information. Because information resided in “silos,” the RCMP’s ability to plan and improve its programs was severely limited.

4.121 The RCMP is aware that its approach to managing case information requires improvement. In a February 2016 report on a proposed disability management and accommodation framework, the RCMP noted the following:

- Reporting required manual cross-referencing from multiple systems, which did not interface.

- Most divisions had their own Excel spreadsheets for tracking and reporting, but these were not accessible nationally.

- Quarterly reporting for off-duty sick leave required more than 230 person-hours of manual intervention to generate each quarterly report.

- Multiple files were maintained for one case, which created a significant risk that documentation on the member’s case would be incomplete.

4.122 As part of its approved 2016 disability case management program, the RCMP planned to put in place a national integrated disability case management information tool by 1 December 2016. However, at the time of the audit, a vendor had not yet been selected, and the timeline for implementation had been moved to September 2017.

4.123 Recommendation. The RCMP should move forward in a timely manner with its plan to put in place a national integrated case management tool to better monitor and manage members’ cases, including their mental health outcomes.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The need for a national integrated case management system has already been identified by the RCMP, and a procurement process to acquire a disability case management solution to support a timely and consistent approach to disability case management is now under way. The disability case management solution will help to facilitate members receiving the support they need to return to work as soon as it is safe for them to do so. The solution, which is projected to be in place in 2018, will also provide a means to monitor and evaluate the performance of the disability management and accommodation program, and to identify trends that highlight potential issues that will be used to inform the disability management and accommodation program, along with occupational health and safety initiatives.

Conclusion

4.124 We concluded that overall, members of the RCMP did not have access to mental health support that met their needs. The RCMP took the important step of introducing a mental health strategy. However, it failed to make implementation of the selected mental health programs and services a priority, and it did not commit the necessary resources to support them. The RCMP is into the third year of the strategy and has the opportunity to make the necessary improvements to ensure its successful implementation by 2019.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s (RCMP’s) delivery of mental health programs and services to its members. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the RCMP’s delivery of mental health programs and services complies in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the Rules of Professional Conduct of Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario and the Code of Values, Ethics and Professional Conduct of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Both the Rules of Professional Conduct and the Code are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit; and

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided.

RCMP management refused to confirm that the findings in this report are factually based, because of disagreement about the approach used to report statistics from the file review and member survey.

Audit objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether RCMP members had access to selected mental health programs and services that met their needs.

Scope and approach

The audit scope included regular and civilian members of the RCMP, and Veterans Affairs Canada’s operational stress injury clinics. We reviewed selected mental health programs and services for all RCMP divisions and conducted site visits with four divisions, including Veterans Affairs Canada’s operational stress injury clinics. We conducted structured interviews with management and staff of the RCMP and of the operational stress injury clinics of Veterans Affairs Canada.

The mental health programs and services we examined include the Road to Mental Readiness program, the Peer-to-Peer program, Periodic Health Assessments, RCMP divisional health services offices, external psychotherapeutic services of the Health Care Entitlements and Benefits Program (including the operational stress injury clinics), and disability case management (medical leave, return to work, and medical discharge). These programs and services support two key areas of the RCMP’s 2014–2019 Mental Health Strategy: early detection and intervention, and continuous improvement.

We did not examine progress against the other key areas of the RCMP Mental Health Strategy—promotion, education, and prevention—and we did not audit the overall success of the RCMP Mental Health Strategy. We therefore did not examine whether the RCMP proactively protects members from the impacts of psychological risks through its programs that support these key areas.

To find out whether RCMP members had access to mental health programs and services that met their needs, we interviewed RCMP officials, reviewed information provided by the organization, and documented the process used to support early detection and intervention for members with mental health conditions. We examined how the RCMP planned to implement the selected programs and services, whether members’ access to the programs and services was timely and reasonable, whether the RCMP had systems and practices in place to know whether the programs and services met members’ needs, and whether the RCMP used performance information to continuously improve service delivery to members.

We used a variety of sources to obtain a more complete understanding of RCMP mental health services delivery. We conducted an electronic survey of 22,237 regular and civilian RCMP members across Canada. In total, 6,769 of members responded (30 percent). In addition, we conducted a hard-copy survey of 828 members on off-duty sick leave. Of these, 261 members responded (31 percent). We then used representative sampling to review 51 medical case files, which included 46 regular members and 5 civilian members. This sample was sufficient to conclude on the population with a margin of error within 10 percent, 18 times out of 20. Finally, during the audit, 33 members from across Canada contacted the audit team to tell their stories. We conducted in-depth interviews with 30 of those members, and we reviewed the written information provided by the remaining 3 members. Of the 30 members we interviewed, 5 were also part of the representative medical case file review.

Criteria

To determine whether the Royal Canadian Mounted Police members had access to selected mental health programs and services that met their needs, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The RCMP has a business plan for implementation of selected mental health programs and services that is aligned with the Mental Health Strategy. |

|

|

The RCMP facilitates members’ timely and reasonable access to the selected internal mental health programs and services they need. |

|

|

The RCMP facilitates members’ timely and reasonable access to the selected third-party mental health programs and services they need. |

|

|

The RCMP has implemented a performance measurement and monitoring framework to know how well it is managing members’ mental health. |

|

|

The RCMP has implemented a quality assurance framework to ensure that its internal mental health programs and services meet members’ needs. |

|

|

The RCMP has implemented a quality assurance framework to ensure that mental health programs and services provided by third parties meet members’ needs. |

|

|

The RCMP uses the performance and quality assurance information it collects to continuously improve the mental health programs and services that it provides to members. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between January 2012 and December 2016. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. The RCMP Mental Health Strategy (2014–2019) was implemented in 2014, but was developed between 2012 and 2014. We examined selected mental health programs and services that supported the strategy to determine whether members’ mental health needs were met. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of the audit.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 27 February 2017, in Ottawa, Ontario.

Audit team

Principal: Joanne Butler

Director: Linda Dimitra Jones

Patricia Begin

Nicole Léger

Robyn Roy

Crystal St-Denis

Yara Tabbara

Marie-Eve Viau

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Meeting members’ mental health needs

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|