2017 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 1—Phoenix Pay Problems

2017 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 1—Phoenix Pay Problems

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- State of pay operations

- The number of pay problems continues to increase

- Public Services and Procurement Canada did not have a full understanding of the extent and causes of pay problems

- Departments and agencies had significant difficulties in providing timely and accurate pay information and in supporting employees in resolving pay problems

- Way forward

- State of pay operations

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1.1—The process to change pay for an employee in departments and agencies serviced by the Miramichi Pay Centre

- 1.2—The number of public servants with outstanding pay requests in 46 departments and agencies quadrupled since Phoenix was launched

- 1.3—The number of outstanding pay requests for 46 departments and agencies grew more than five times what it was when Phoenix was launched

- 1.4—The Miramichi Pay Centre processed more pay requests than it took in only twice after Phoenix was launched in February 2016

- 1.5—Percentage of employees with errors in their paycheques increased across all departments and agencies

- 1.6—Case study: Clear governance helped Queensland Health resolve its employee pay problems

- 1.7—Pay requests with high financial impact made up more than half the outstanding pay requests

Introduction

Background

1.1 In 2009, the Government of Canada began to transform the way it processed pay for its 290,000 employees. Public Services and Procurement Canada was responsible for this Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative. The initiative had two projects: one to centralize pay services for 46 departments and agencies that employed about 70 percent of all federal employees, and the other to replace the 40-year-old pay system used by 101 departments and agencies.

1.2 The pay transformation initiative, which took seven years to complete, cost $310 million. The government expected the initiative to save it about $70 million a year, starting in the 2016–17 fiscal year.

1.3 Before pay services were centralized, each department and agency processed pay for its own employees and had its own pay advisors—specialists who processed pay, advised employees, and corrected errors. There were about 2,000 pay advisors across 101 departments and agencies.

1.4 One of the roles of pay advisors is to make sure that changes stemming from pay requests are processed in the pay system. Pay requests can be anything from a request to change an employee’s address or bank account information or a request to enter parental leave or overtime, to a request to fix a pay error that resulted in overpaying or underpaying an employee.

1.5 In May 2012, Public Services and Procurement Canada began to centralize pay advisors for 46 departments and agencies in the new Public Service Pay Centre in Miramichi, New Brunswick. Approximately 1,200 pay advisor positions in those 46 departments and agencies were eliminated by early 2016 and replaced with 460 pay advisors and 90 support staff at the Miramichi Pay Centre. As a result, the 46 departments and agencies no longer had responsibility for entering data directly into the pay system and did not have direct access to the new pay system—this work would be done by the pay advisors in Miramichi. The other 55 departments and agencies kept their approximately 800 pay advisors and continued to enter pay information for their own employees in the new system.

1.6 The government’s 40-year-old pay system had many manual processes, which were completed by pay advisors. The system chosen to replace it was a PeopleSoft commercial pay system, which was customized to meet the government’s needs and which was to automate many of those manual processes. This system was called Phoenix by Public Services and Procurement Canada. The Department hired International Business Machines CorporationIBM to help it design, implement, integrate, customize, and deploy Phoenix. Phoenix was launched in two waves: The first wave included 34 departments and agencies in February 2016, and the second wave included an additional 67 departments and agencies in April 2016. The expectation was that once Phoenix was implemented, the 460 pay advisors in the Miramichi Pay Centre would be able to do the work of the previous 1,200 pay advisors in the 46 departments and agencies that became clients of the Pay Centre.

1.7 The implementation of Phoenix was complex. There were more than 80,000 pay rules that needed to be programmed into Phoenix. This is because there are more than 105 collective agreements with federal public service unions, as well as other employment contracts. In addition, many departments and agencies have their own human resource systems to manage employees’ permanent files that include basic information such as address, job classification, rate of pay, and types of benefits. Phoenix needs some of this information to accurately process pay, so the 34 human resource systems across the Government of Canada needed an interface to share information with Phoenix. As a result, to handle these pay rules and interfaces with human resource systems, Public Services and Procurement Canada added more than 200 custom-built programs to Phoenix.

1.8 Public Services and Procurement Canada. Public Services and Procurement Canada is responsible for developing, operating, and maintaining Phoenix and communicating instructions to Phoenix users. Public Services and Procurement Canada is also responsible for administering the pay of public service employees. Its responsibility for the 46 departments whose pay services were centralized at the Miramichi Pay Centre includes the direct input of information into Phoenix to initiate, change, or terminate pay for employees, based on requests and information received from the departments. This input is done by the Miramichi pay advisors. The other 55 departments are responsible for modifying pay information in Phoenix for their employees.

1.9 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat supports the Treasury Board in its role as the employer of the public service in determining and regulating pay, hours of work, and other terms and conditions of employment, and in entering into collective agreements with unions. The Secretariat provides departments with direction and guidance about how to implement Treasury Board pay policies. The Secretariat also promotes government-wide sharing of information and best practices on pay and provides documented business processes for human resources.

1.10 Departments and agencies. Departments and agencies are responsible for ensuring that their human resource systems and supporting processes are compatible and integrated with Phoenix. They must ensure that complete and accurate information needed to pay their employees is sent on time to Phoenix, either through the Miramichi Pay Centre for the 46 departments and agencies using the centre, or directly for the other 55 departments and agencies. Departments and agencies must also review and authorize pay to be issued to employees.

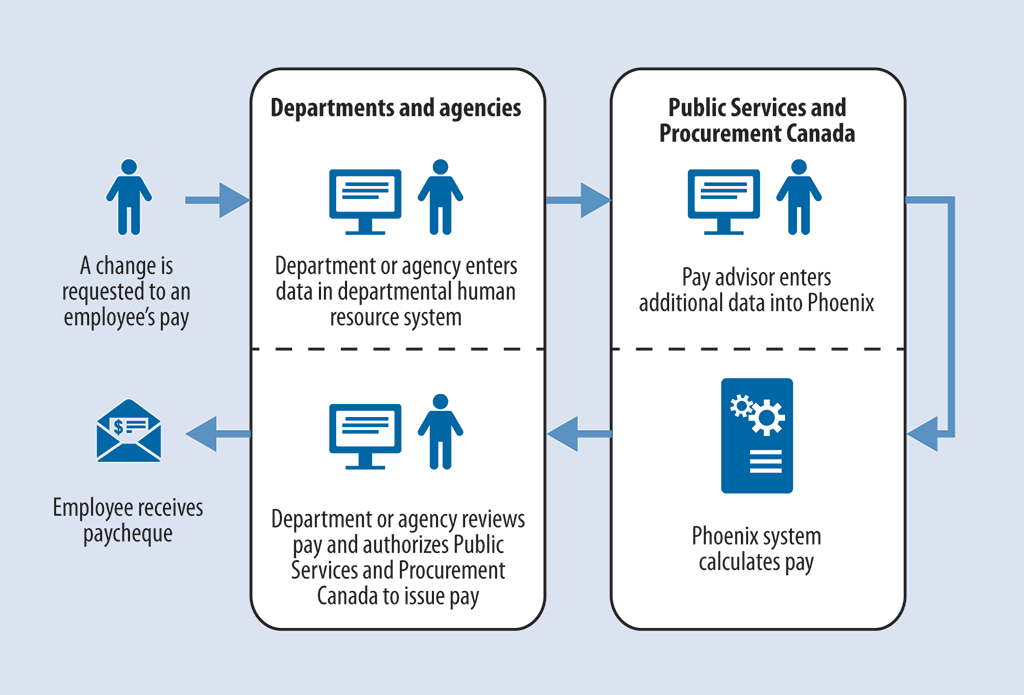

1.11 All departments and agencies, including Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, have a shared accountability for paying employees in a timely and accurate manner. They must all comply with the terms and conditions of employment of federal employees, including standards on paying employees accurately within a specific time frame. Exhibit 1.1 illustrates the roles and responsibilities for processing a typical pay request of an employee in a department or agency serviced by the Pay Centre.

Exhibit 1.1—The process to change pay for an employee in departments and agencies serviced by the Miramichi Pay Centre

Exhibit 1.1—text version

This diagram shows the process to change pay, resulting from a pay request, for an employee of a department or agency serviced by the Miramichi Pay Centre.

- A change is requested to an employee’s pay.

- The department or agency enters data in its human resource system.

- A pay advisor from Public Services and Procurement Canada enters additional data into Phoenix.

- The Phoenix system calculates pay.

- The department or agency reviews the pay amount and authorizes Public Services and Procurement Canada to issue pay.

- The employee receives a paycheque.

Focus of the audit

1.12 This audit examined whether Public Services and Procurement Canada, working with selected departments and agencies, resolved pay problems in a sustainable way to ensure that federal government employees would receive their correct pay, on time.

1.13 The 12 departments and agencies included in the audit were

- the Canada School of Public Service,

- the Canadian Security Intelligence Service,

- Correctional Service Canada,

- Employment and Social Development Canada,

- National Defence,

- Natural Resources Canada,

- the Privy Council Office,

- Public Services and Procurement Canada,

- the Royal Canadian Mounted Police,

- Shared Services Canada,

- Statistics Canada, and

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

1.14 This audit is important because the federal government’s pay problems have financially affected thousands of its employees. These problems need to be resolved in order to ensure that federal employees are paid accurately and on time. The government’s current annual payroll is about $22 billion.

1.15 We did not examine the events and decisions that led to the implementation of the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative, including the centralization of pay advisors and the launch of Phoenix. The implementation of Phoenix is the focus of a future audit.

1.16 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

State of pay operations

Overall message

1.17 Overall, we found that a year and a half after the Phoenix pay system was launched, the number of public servants in departments and agencies using the Miramichi Pay Centre who had an outstanding pay request quadrupled to more than 150,000. Departments and agencies have struggled with pay problems since the launch of Phoenix. However, it took Public Services and Procurement Canada four months to recognize that there were serious pay problems, and it took the Department about a year after that to have a better understanding of the problems. During this time, the Department focused on responding to the growing number of pay requests. At the end of our audit, the Department had started to develop a longer-term plan toward a sustainable solution.

1.18 The problem grew to the point that as of 30 June 2017, unresolved errors in pay totalled over half a billion dollars. This amount consisted of money that was owed to employees who had been underpaid plus money owed back to the government by other employees who had been overpaid.

1.19 In addition, departments and agencies struggled to do the tasks they were responsible for in paying their employees under Phoenix. Public Services and Procurement Canada did not provide sufficient information and reports to help departments and agencies understand and resolve their employees’ pay problems.

1.20 This is important because the federal government has an obligation to pay its employees on time and accurately. Not doing so has had serious financial impacts on the federal government and its employees.

The number of pay problems continues to increase

1.21 We found that the number of outstanding pay requests in departments and agencies using the Miramichi Pay Centre was significantly higher than the number reported by Public Services and Procurement Canada. The Department excludes certain types of pay requests in its calculation of the total number of outstanding requests. We found that between the time Phoenix was launched and the end of our audit period in June 2017, the number of outstanding pay requests had continued to grow to over 494,500.

1.22 Since Phoenix was launched, there were only two months in which the Miramichi Pay Centre processed more pay requests than it took in, and the number of outstanding pay requests continued to grow. We found that employees had to wait an average of more than three months to have a pay request processed. At the end of our audit period, nearly 49,000 employees had been waiting for more than a year to have pay requests processed. Two thirds of these employees had a pay request that Public Services and Procurement Canada deemed to have a high financial impact, which it defined as over $100.

1.23 As of 30 June 2017, there was over $520 million in pay outstanding due to errors for public servants serviced by Phoenix who were paid either too much or too little. We found that the number of payroll payments that contained an error increased over the 2016–17 fiscal year. We calculated that about 51 percent of employees had errors in their paycheques issued on 19 April 2017, compared with 30 percent in the pay issued on 6 April 2016. These error rates were significantly higher than what Public Services and Procurement Canada targeted.

1.24 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

1.25 This finding matters because the federal government is obligated to pay its employees on time and accurately. Not doing so has had serious financial impacts on the federal government and its employees.

1.26 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.59.

1.27 What we examined. We examined information that Public Services and Procurement Canada, as well as other audited departments and agencies, had on outstanding and processed employee pay requests. We also examined information about how long it took to resolve pay problems. Using the same sample of employees that was examined for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s annual audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the fiscal year ending 31 March 2017, we determined the error rate of pay processed during each bi-weekly pay period.

1.28 Outstanding pay requests. After the Miramichi Pay Centre was created, Public Services and Procurement Canada began tracking the number of pay requests for employees in the departments and agencies using the Pay Centre. This number gradually grew as more departments and agencies transferred their pay files and related requests to Miramichi. As of February 2016, just before the launch of Phoenix, there were approximately 35,900 employees with 95,600 outstanding pay requests.

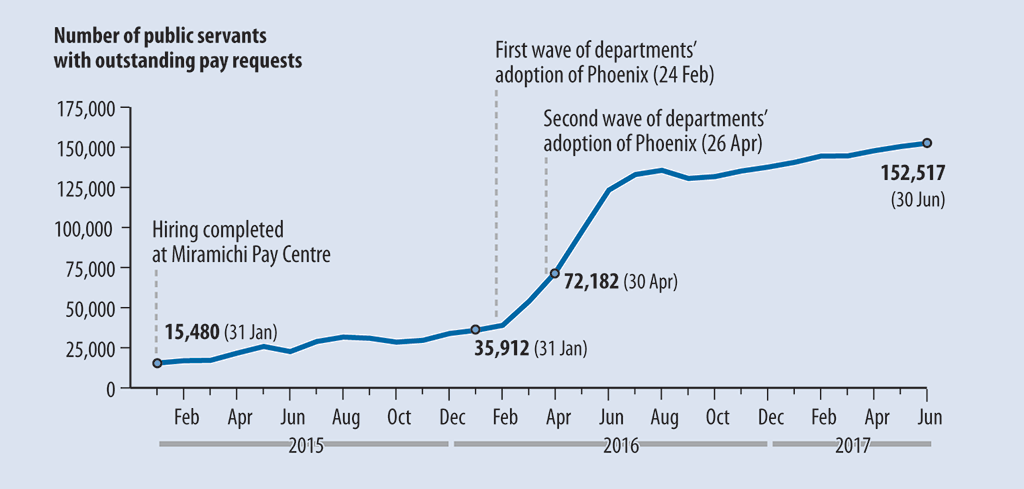

1.29 As Phoenix was going through its first and second wave of departments and agencies adopting the new pay system, the number of employees with an outstanding pay request doubled, from 35,900 to 72,200. By June 2017, this number had grown to over 150,000 employees—more than four times the number when Phoenix was launched (Exhibit 1.2). That means that most of the employees in those 46 departments and agencies were waiting for pay requests to be processed. In addition, the number of outstanding pay requests grew by five times, from 95,600 when Phoenix launched to 494,500 in June 2017 (Exhibit 1.3).

Exhibit 1.2—The number of public servants with outstanding pay requests in 46 departments and agencies quadrupled since Phoenix was launched

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 1.2—text version

This line graph shows that the number of public servants with outstanding pay requests in the 46 departments and agencies serviced by the Miramichi Pay Centre quadrupled from the end of January 2016, just before Phoenix was launched, to the end of June 2017. The graph provides information for specific dates between January 2015 and June 2017:

- 31 January 2015—15,480 public servants had outstanding pay requests. Hiring at the Miramichi Centre was completed.

- 31 January 2016—35,912 public servants had outstanding pay requests.

- 24 February 2016—Phoenix was adopted in a first wave by departments and agencies.

- 26 April 2016—Phoenix was adopted in a second wave by departments and agencies.

- 30 April 2016—72,182 public servants had outstanding pay requests.

- 30 June 2017—152,517 public servants had outstanding pay requests.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 1.3—The number of outstanding pay requests for 46 departments and agencies grew more than five times what it was when Phoenix was launched

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 1.3—text version

This line graph shows a fivefold increase in the number of outstanding pay requests in the 46 departments and agencies serviced by the Miramichi Pay Centre from the end of January 2016, just before Phoenix was launched, to the end of June 2017. The graph provides information for specific dates within this time span:

- 31 January 2015—There were 41,774 outstanding pay requests. Hiring at the Miramichi Centre was completed.

- 31 January 2016—There were 95,589 outstanding pay requests.

- 24 February 2016—Phoenix was adopted in a first wave by departments and agencies.

- 26 April 2016—Phoenix was adopted in a second wave by departments and agencies.

- 30 April 2016—There were 206,223 outstanding pay requests.

- 30 June 2017—There were 494,534 outstanding pay requests.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

1.30 In April 2017, Public Services and Procurement Canada began processing back pay resulting from the retroactive signing of several new collective agreements with federal public service unions. The collective agreements required increases in pay going as far back as four years. Almost 40 percent of the pay increases could not be processed automatically in Phoenix and had to be processed manually by the Miramichi Pay Centre. Public Services and Procurement Canada tracks the processing of these pay increases separately, so they were not counted among the number of outstanding pay requests.

1.31 The numbers we used in our analysis of the outstanding pay requests also did not include such requests for the 55 departments and agencies that do not use the Miramichi Pay Centre because this information is not available from these departments. In spring 2017, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat started to gather information about outstanding requests from the 55 departments and agencies that do not use the Pay Centre. We did not examine this information because at the end of our audit period in June 2017, the information gathering was not yet completed.

1.32 In our analysis of the outstanding pay requests, we found that there were significant delays in processing many different types of pay requests, including for

- employees on leave, such as parental leave;

- employees who had received promotions;

- employees who transferred from one department to another; and

- new employees, such as summer students.

1.33 The number of outstanding pay requests that we calculated was about 29 percent higher than the number reported by Public Services and Procurement Canada. The Department excluded pay requests that in its view did not have a financial impact on employees, did not require significant effort from pay advisors, might be duplicates, or were related to pay problems reported by employees online or through a call centre it had set up for employees to report problems. We included these requests in our count because a pay advisor has to look at all of the pay requests to know what the financial impact is. Even if there is no financial impact or the pay request is a duplicate, it requires effort from a pay advisor to confirm this and to close the request, which means that all of the pay requests require some processing. Moreover, these pay requests are counted by the Department in its number of processed requests.

1.34 We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not conduct a thorough analysis of the financial impacts of the pay requests it excluded from its count, such as those related to records of employment, emergency salary advancements, tax slips, benefits information, and beneficiary forms. While these may not have an immediate financial impact on payroll, they may have a financial impact on the employee later if the information is not processed in a timely manner.

1.35 Processing times of pay requests. The federal government’s terms and conditions of employment require most changes in pay to be made in the second pay period following the one in which the change was requested. This means that the change in pay would be received about 30 days later. At the end of our examination, we found that employees waited an average of more than three months to have pay requests processed. We also found that at that time, about 49,000 employees had waited for over a year for Public Services and Procurement Canada to process one or more pay requests. Of these employees, approximately 32,500 had an outstanding pay request with a high financial impact, which Public Services and Procurement Canada defines as $100 or more.

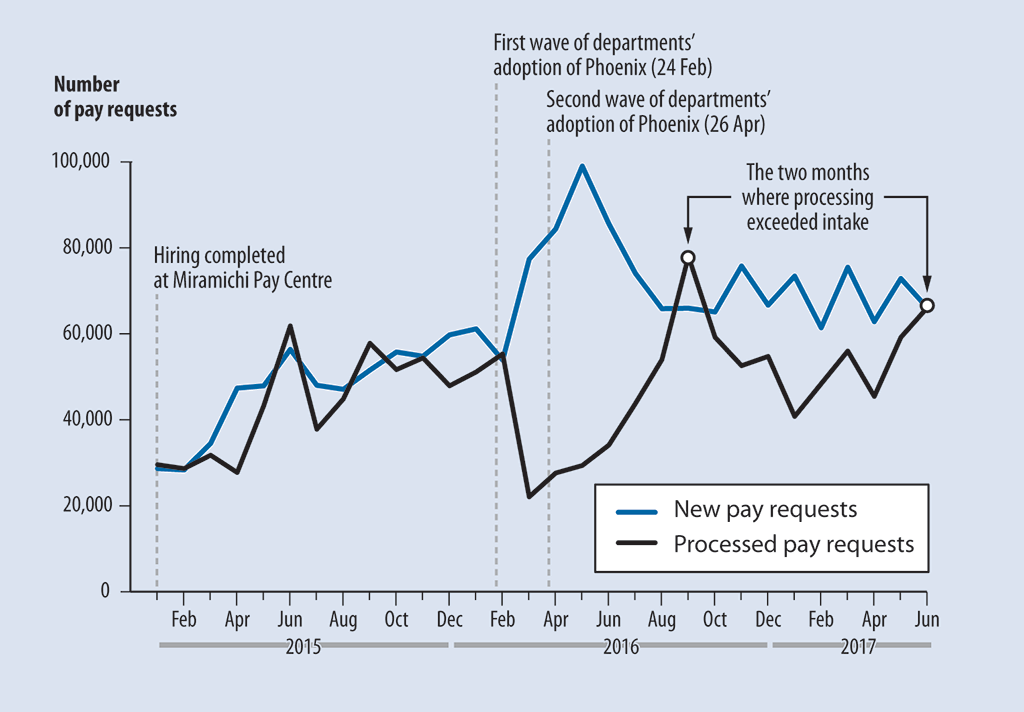

1.36 We also found that since Phoenix launched in February 2016, there were only two months in which the Miramichi Pay Centre processed more pay requests than it took in (Exhibit 1.4). As a result, the number of outstanding pay requests continued to grow (Exhibit 1.3).

Exhibit 1.4—The Miramichi Pay Centre processed more pay requests than it took in only twice after Phoenix was launched in February 2016

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 1.4—text version

This line graph shows changes in the numbers of new and processed pay requests at the Miramichi Pay Centre from January 2015, when hiring at the Miramichi Pay Centre was completed, to June 2017. For most months shown, the numbers of new pay requests exceeded the numbers of processed pay requests. The following two exceptions occurred:

- Before departments and agencies adopted Phoenix (on 24 February 2016 for the first wave and on 26 April 2016 for the second wave), there were three months in which the number of processed pay requests exceeded the number of new pay requests—June 2015, September 2015, and February 2016. The processing data was gathered at the end of each month. This means that although the February 2016 data was gathered 5 days after the launch of Phoenix, it mostly reflects the intake and processing numbers before the launch.

- After departments and agencies adopted Phoenix, there were two months in which the number of processed pay requests exceeded the number of new pay requests—September 2016 and June 2017.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

1.37 Our recommendation to address the growing number of outstanding pay requests appears in paragraph 1.59.

1.38 Pay errors. A pay error is a delay in pay or an underpayment or overpayment. It can be caused by Phoenix when it calculates payroll, or it can be caused by a delay or error in inputting information into Phoenix. Examples of pay errors include

- employees not being paid for overtime;

- employees who work shift work not being paid for all the hours that they worked at the correct rate;

- employees who transferred from one department to another being paid by both departments; and

- employees not receiving correct pay when acting in a temporary role for a superior, or not receiving pay increases related to promotions on time because of late input into Phoenix.

1.39 As reported in the Observations of the Auditor General of Canada on the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the year ended 31 March 2017, we found that 62 percent of the employees in our sample were paid incorrectly at least once during the 2016–17 fiscal year.

1.40 Using the same sample of employees we used for our audit of the consolidated financial statements, we analyzed how many employees had errors in each bi-weekly pay that was issued. Based on that sample, we found that about 30 percent of employees had at least one error in the first pay period of the 2016–17 fiscal year, which then increased to 51 percent in the last pay period of that same fiscal year (Exhibit 1.5). These error rates were significantly higher than what Public Services and Procurement Canada targeted. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada was not tracking errors in pay and did not know how many outstanding pay requests were pay errors that needed to be corrected. The Department told us that the causes and sources of errors are so varied, it is unreasonable to expect it to track and measure them. However, this information is important for Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies to determine what actions are needed to address the problems. As the administrator and owner of the pay system, Public Services and Procurement Canada is the department with the most information to be able to analyze and track the source of errors across government.

Exhibit 1.5—Percentage of employees with errors in their paycheques increased across all departments and agencies

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of a sample of employees’ pay transactions used in the audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the year ended 31 March 2017

Exhibit 1.5—text version

This line graph shows changes in the percentages of employees with errors in their paycheques by pay period from 20 April 2016 to 19 April 2017. The percentage increased across all departments and agencies during this time span, with paycheque errors affecting 30% of employees on 20 April 2016 and 51% of employees on 19 April 2017.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of a sample of employees’ pay transactions used in the audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the year ended 31 March 2017

1.41 As the number of outstanding pay requests grew, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat asked all departments and agencies, including those not using the Miramichi Pay Centre, to estimate the number of employees affected by pay errors and the total amounts of these errors. As of June 2017, departments and agencies reported that the government owed 51,000 employees a total of $228 million (because the employees were underpaid) and 59,000 employees owed the government a total of $295 million (because they were overpaid). In other words, there were over $520 million worth of pay errors that still needed to be corrected.

Public Services and Procurement Canada did not have a full understanding of the extent and causes of pay problems

1.42 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not have a full understanding of the extent and causes of pay problems. Until about a year after Phoenix was launched, the Department was still responding to pay problems as they arose. The Department then began proposing a roadmap of projects to start resolving the problems, based on work done by an external consultant. However, by the end of our audit period in June 2017, this roadmap was still being finalized.

1.43 Public Services and Procurement Canada identified, tracked, and devoted significant effort to resolving pay problems. However, it has not fully addressed the underlying causes of pay problems or developed a long-term sustainable solution.

1.44 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

1.45 This finding matters because without a full understanding of the causes of pay problems, Public Services and Procurement Canada cannot work with departments and agencies to resolve pay problems and achieve the efficiencies expected to result from the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative.

1.46 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 1.59 and 1.60.

1.47 What we examined. We examined whether Public Services and Procurement Canada identified pay problems and analyzed the nature and extent of those problems. To better understand the effect of Phoenix on the pay process, we sent a survey to a sample of pay advisors working in the Miramichi Pay Centre, the temporary pay centres that the Department established, and two departments that process their own pay.

1.48 Identifying and understanding pay problems. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada took several steps to identify and understand problems with pay, such as

- setting up a call centre, online form, and email address for employees to report pay problems;

- creating a help desk for pay advisors who process pay to report problems;

- preparing reports from Phoenix and sharing them with departments and agencies to identify possible overpayments;

- tracking Phoenix software problems that needed to be resolved; and

- hiring consultants to identify and group problems and causes, and to propose solutions.

1.49 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada tracked pay-related problems in a number of information technology systems, spreadsheets, and lists, and retrieved information from those sources when it prepared status reports about pay problems.

1.50 We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada only did limited analysis to determine the underlying causes of pay problems. The following are some examples:

- The Department stated that it analyzed the underlying causes of problems reported by employees. However, we found that this analysis was not thorough and did not determine underlying causes.

- The Department generated reports that identified possible overpayments, and sent the reports to departments and agencies, which used them to determine whether there were actual pay problems that needed to be resolved. However, Public Services and Procurement Canada did not follow up with departments and agencies to determine whether the identified potential pay problems were in fact errors or what caused them.

- Phoenix has about 200 custom programs to handle some of the 80,000 federal government pay rules, and to work with departmental human resource systems to process pay. Public Services and Procurement Canada determined that it needed to analyze all 200 of these programs to identify the system-related sources of pay errors. However, the Department started its analysis only in March 2017—more than a year after pay problems started to be reported—and by the end of our examination, it had analyzed only 6 of the 200 custom programs.

1.51 We noted that Public Services and Procurement Canada hired several consulting firms, including IBM, the consulting firm that helped implement Phoenix, to perform some focused analysis and recommend actions to resolve problems. The Department developed action plans to implement key recommendations from the analysis. In 2017, the Department hired another consulting firm to perform a more thorough analysis of problems and causes and recommend a longer-term plan for resolving problems government-wide. This analysis proposed a roadmap with 40 potential projects over three years. At the end of June 2017, this roadmap was still being finalized.

1.52 Public Services and Procurement Canada initially believed that many of the pay problems were caused by departmental employees, managers, and pay advisors not understanding how and when to enter information into Phoenix. By January 2017, the Department acknowledged that the causes of pay problems were more complex and required the collaboration of all stakeholders, including the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and departments and agencies.

1.53 We found that there were many causes of pay problems. For example, Phoenix was designed to process pay details entered in real time. However, departments and agencies were processing a significant number of their pay requests retroactively. This contributed significantly to the rising number of outstanding pay requests. One type of retroactive pay request is acting pay, which is provided to an employee who is acting in a temporary role for a superior. About 1 in 4 outstanding pay requests was related to acting pay. Phoenix was supposed to automatically process retroactive acting pay requests when it launched in 2016, but this functionality was deferred until March 2017. Public Services and Procurement Canada reports showed that, even after the implementation of this functionality, 40 percent of acting pay requests still required some manual processing because of the large number of possible acting pay scenarios.

1.54 Another issue that caused pay problems was that Public Services and Procurement Canada discovered, after it launched Phoenix, that entering certain types of data into the system while the system was calculating pay caused errors. As a result, the Department restricted user access to the system when it was calculating pay. Therefore, pay advisors could not access parts of Phoenix for about 5 working days out of every pay cycle of 10 working days. Although Public Services and Procurement Canada put in place a manual workaround, we found that this caused additional problems. The Department told us that it was developing a permanent solution.

1.55 Another cause of pay problems was that Phoenix was not designed to automatically process the complex shift work rules of several categories of employees, such as correctional officers, Coast Guard officers and crew, and nurses, which account for almost 10 percent of federal public servants. As a result, departments with employees subject to those rules found that processing those employees’ pay was cumbersome and prone to error. This required extensive manual and customized processes outside Phoenix to get those employees paid accurately and on time.

1.56 For us to better understand the extent of pay problems caused by Phoenix, we sent a survey to pay advisors across Canada. They were working in the Miramichi Pay Centre, in the temporary pay offices that the Department established across the country to help process outstanding pay requests, and in two departments that process their own pay. The respondents reported that they did not receive enough training to do their work, that their workload was very high, and that they often had to re-input pay requests that had been rejected by Phoenix and often did not know why the requests were rejected. In addition, pay advisors had to deal with shifting priorities, which added to their stress levels.

1.57 When the number of pay problems increased significantly after the launch of Phoenix in 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada took several steps to try to reduce the problems. It provided human resources staff in other departments and agencies with more training to help them understand how and when to enter data correctly into their human resource systems. It also opened satellite pay centres with additional pay advisors. More recently, in the spring of 2017, the Department began to hire more staff at the Miramichi Pay Centre and train staff in departments as pay advisors to help process pay requests for their departments.

1.58 These steps that Public Services and Procurement Canada took did not reduce the number of outstanding pay requests, which, as our earlier analysis shows (see paragraphs 1.21 to 1.41), was still growing at the end of our audit period. Once the Department reduces the number to a level that will allow it to pay employees accurately and on time, Phoenix will still not be achieving the expected productivity improvements from the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative. Public Services and Procurement Canada told us that to achieve these efficiencies, the Department, with the cooperation of departments and agencies, needs to do the following:

- improve governance to oversee the development of a long-term sustainable solution by working with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and departments and agencies;

- improve the functionality and performance of Phoenix;

- improve the efficiency and effectiveness of business processes, improve data quality, and establish performance standards;

- enhance system and resource capacity and productivity; and

- work with departments to align current pay processes with Phoenix.

1.59 Recommendation. Public Services and Procurement Canada, in partnership with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and departments and agencies, should conduct an in-depth analysis of the causes of pay problems to determine what solutions are needed to resolve them.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The causes of pay problems are complex, exist at each stage in the human resources-to-pay (HR-to-pay) process, and involve many stakeholders. Further, these complexities were not well understood at the time of implementing the Phoenix information technologyIT solution. Building on the analysis and lessons learned conducted to date, Public Services and Procurement Canada, in partnership with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and departments and agencies, is developing an HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan reflective of this in-depth analysis of the causes of pay problems and the integrated and effective solutions needed to resolve them. The HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan is comprehensive and will be multi-phased. It is evergreen and will incorporate additional analysis as it becomes available. Oversight on the progress and outcomes of the implementation of the Integrated Plan will be provided by the government-wide Governance Framework. A preliminary HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan for Phase I will be finalized by December 2017.

1.60 Recommendation. Public Services and Procurement Canada, with the support of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and in partnership with departments and agencies, should develop a sustainable pay solution, which includes

- a thorough analysis of possible options for a sustainable solution that includes detailed cost information; and

- a complete and comprehensive plan for implementing the chosen option, including alignment to human resource systems and processes, timelines, accountability, and costs.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The integration of human resources (HR) with pay has resulted in a need to consider solutions taking into account the continuum of HR interventions that lead to pay actions. As part of the HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan, Public Services and Procurement Canada, with the support of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and in partnership with departments and agencies, will review long-term options to develop a sustainable pay solution that fully considers the complexity of the HR-to-pay environment. The HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan is comprehensive and will be multi-phased. It identifies an integrated and effective solution, and ensures an alignment of governance, human resources, systems, processes and controls, and change management. It is evergreen and will incorporate additional analysis as it becomes available. Oversight on the progress and outcomes of the implementation of the Integrated Plan will be provided by the government-wide Governance Framework. A preliminary HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan for Phase I will be finalized by December 2017.

Departments and agencies had significant difficulties in providing timely and accurate pay information and in supporting employees in resolving pay problems

1.61 We found that departments and agencies often could not meet the processing deadlines required by Phoenix, which led to pay errors. We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not always provide departments and agencies with sufficient time in the pay system to review paycheques before they were issued, or provide them with timely and accurate information for them to support their employees in resolving pay problems. We also found that the pay problems had an effect on the wellness of pay advisors and increased the workload of pay and finance staff in departments and agencies.

1.62 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

1.63 This finding matters because the difficulties experienced by department and agency staff as well as Miramichi Pay Centre staff not only affect their ability to get employees paid the right amount on time, but also affect the reputation of the federal public service as a place to work.

1.64 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 1.73 and 1.74.

1.65 What we examined. We examined whether selected departments and agencies fulfilled their responsibilities to send timely pay information to Public Services and Procurement Canada and to review pay before it was issued. We also examined whether Public Services and Procurement Canada provided departments and agencies with the information they needed to understand the nature and extent of their employees’ pay problems and to try to resolve them.

1.66 Processing pay. To process each payroll, all departments and agencies must provide pay information to Public Services and Procurement Canada, which then uses Phoenix to calculate and issue pay based on that information. Departments and agencies must also review paycheques and authorize them before they are issued to employees.

1.67 Of the seven departments and agencies we examined as a sample of the departments and agencies using Phoenix, five were serviced by the Miramichi Pay Centre and two were not. All seven faced significant difficulties in providing timely and accurate pay information to Phoenix and were not tracking their performance in these areas. For example, Phoenix is set up to receive information about new hires on the day they start work. However, departments did not adjust their processes to align with the Phoenix timelines and continued sending the pay requests after the date of hire. Public Services and Procurement Canada did an analysis in early 2017 and found that these requests were submitted on average 8 to 10 days after the employee started work. The Department also analyzed delays in submitting pay requests for employees returning from leave. It shared its analysis with departments and agencies, which questioned the accuracy and usefulness of the analysis.

1.68 To help improve timeliness and accuracy, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat committed in April 2017 to developing service standards for departments and agencies.

1.69 Department and agency activities to resolve pay problems. We found that because their access to Phoenix was restricted, departments and agencies could not always review paycheques before they were issued to ensure that correct payments would be issued to employees. Often, Public Services and Procurement Canada would provide last-minute notice about when the system would be available, and departments would have to perform their reviews in the evening or on weekends. Because departments and agencies could not always exercise their pay review control, they might have missed some payment errors. These wrong payments would then have had to be corrected through a pay request that had to be placed in the queue.

1.70 To resolve pay problems, departments and agencies need information that can be provided only by Public Services and Procurement Canada as the administrator of Phoenix. Public Services and Procurement Canada provided information to departments through a variety of ways, but it was not always sufficient or timely. For example, Public Services and Procurement Canada communicated to departments the rate and reason for rejecting pay requests. These reasons included incomplete documentation and information and missing required signatures. Public Services and Procurement Canada told us that it expected departments to then determine the causes of these problems for the rejected pay requests they and their employees submitted. However, Public Services and Procurement Canada did not keep copies of the rejected requests to provide to departments to help them to resolve the problems, and neither did most departments.

1.71 Because the number of their employees with pay problems was increasing, and because they did not have all the information they needed, departments and agencies took their own actions to try to resolve pay problems. We found the following examples:

- Many departments and agencies set up their own liaison offices with additional staff where employees could escalate pay problems and get support to resolve them.

- A number of departments and agencies created interdepartmental committees to try to resolve common pay problems.

- One agency, Correctional Service Canada, adapted its existing shift work system and worked with Public Services and Procurement Canada to allow it to transmit data to Phoenix. The Agency has more than 7,000 correctional officers, who work shifts at 43 institutions.

- Another agency, Statistics Canada, kept its existing pay system for temporary employees it hired to work on the 2016 Census, rather than using Phoenix.

1.72 The extent of pay problems also affected the wellness of the pay advisors at the Miramichi Pay Centre and in departments and agencies. Through our survey of, and our interviews with, pay advisors, we learned that they wanted to deliver good service and process pay on time. However, the lack of complete and accurate procedures, the number of outstanding pay requests, and an inability to predict how Phoenix would process pay requests meant that the pay advisors could not deliver a level of service of which they could be proud. This meant that they could not keep up with the problems and felt extensive fatigue, stress, and low morale. We also found, as part of our survey of costs related to the pay system, that many departments and agencies reported an increased workload and work pressures on staff in their human resource and finance functions.

1.73 Recommendation. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should

- establish with Public Services and Procurement Canada timelines for departments and agencies to submit accurate pay information that will enable them to meet the terms and conditions of employment; and

- support Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies in the development of performance measures to track and report on the accuracy and timeliness of pay.

The Secretariat’s response. Agreed. As part of the HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, in collaboration with Public Services and Procurement Canada, will establish standardized timelines for human resources transactions leading to a pay action by 30 June 2018. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, in collaboration with Public Services and Procurement Canada, will concurrently work with departments and agencies to establish and implement standardized HR-to-pay business processes going forward.

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, in collaboration with Public Services and Procurement Canada, will establish performance measures to be implemented starting in the 2018–19 fiscal year, which will assist in the tracking and reporting of pay actions. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will collaborate with Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies to further refine the tracking and reporting of key human resources metrics, including the timeliness of pay.

1.74 Recommendation. Public Services and Procurement Canada should

- work with departments and agencies to identify and provide relevant, accurate, and timely information and reports for them to properly assess pay problems where they have a responsibility to do so; and

- ensure sufficient, reliable, and timely access to the pay system for departments and agencies to process pay requests and to perform checks and authorizations they are responsible for.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The complexity of roles in the HR-to-pay process has created a need for mechanisms to effectively share information with and provide access to stakeholders. As part of the HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan and established governance, Public Services and Procurement Canada is working with departments and agencies to identify and provide relevant, accurate, and timely information and reports, and ensure sufficient, reliable, and timely access to the pay system for departments to allow them to effectively discharge their responsibilities to their employees related to pay problems and Financial Administration Act obligations. The access provided must respect the privacy of employees under the Privacy Act. The HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan is comprehensive and will be multi-phased. It is evergreen and will incorporate additional analysis as it becomes available. Oversight on the progress and outcomes of the implementation of the Integrated Plan will be provided by the government-wide Governance Framework. A preliminary HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan for Phase I will be finalized by December 2017.

Way forward

Overall message

1.75 Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat did not recognize early enough that they needed a comprehensive governance structure to resolve pay problems and develop a sustainable solution. Public Services and Procurement Canada initially responded to pay problems on its own and did not fully involve departments and agencies in developing a plan to resolve pay problems.

1.76 Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies expected to spend $540 million to resolve the pay problems over a three-year period. We believe that this will not be enough to achieve the efficiencies expected from the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative. The Department stated that it was developing a comprehensive plan, including detailed cost information, to resolve pay problems, and that until this is finalized, it cannot provide Parliament with any assurance as to how much it will cost or when it will have a sustainable solution. The government needs to be aware that it may be in a similar situation to Queensland Health, a department in the Australian State of Queensland, which after eight years has spent over CanadianCAN$1.2 billion and continues to resolve problems with its pay system.

1.77 This is important because the government needs to put in place the right governance structure and understand the effort needed and the cost to develop a sustainable solution for timely and accurate pay.

There was no comprehensive governance structure in place to resolve pay problems in a sustainable way

1.78 We found that 16 months after the pay problems first arose, there was still no comprehensive governance structure to resolve the underlying causes of the problems. In contrast, Queensland Health, a government department in the Australian State of Queensland, which had similar problems with a pay system, put in place a comprehensive governance structure within four months of pay problems arising.

1.79 Public Services and Procurement Canada developed multiple plans to react to pay problems as they arose. However, these plans were not integrated and did not reduce the number of outstanding pay requests, which continued to grow. Nor did the plans result in the processing of new pay requests within the timelines specified by the terms and conditions of employment.

1.80 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

1.81 This finding matters because an integrated plan and governance structure is needed to guide government-wide efforts to pay employees accurately and on time, and to find a sustainable solution to the Phoenix pay problems.

1.82 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 1.60 and 1.98.

1.83 What we examined. We examined whether there was comprehensive governance and oversight to resolve pay problems. We looked at whether Public Services and Procurement Canada had worked with departments and agencies to develop and implement responsibilities to resolve problems. We also examined whether Public Services and Procurement Canada had developed and implemented a plan that could be expected to resolve employee pay problems.

1.84 Governance and oversight to resolve pay problems. Public Services and Procurement Canada is responsible for the development, operation, and maintenance of Phoenix in order to provide timely and accurate pay to employees. However, because departments and agencies also have a role to play in providing timely and accurate pay information, this means that Public Services and Procurement Canada should involve them in resolving pay problems. We found that it did not do so fully. Public Services and Procurement Canada’s focus was to pay employees, so it tried to resolve the immediate problems. Although it made progress up to June 2017 in two targeted areas—disability, and maternity and parental leave—it did not reduce the overall growth of outstanding pay requests.

1.85 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat helps Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies by providing direction and guidance on implementing pay policies. In the first year after pay problems surfaced, the Secretariat did not play an active role in supporting Public Services and Procurement Canada to ensure the cooperation and agreement from all departments and agencies in resolving pay problems.

1.86 We found that for the first 16 months after the pay problems started to surface, there was no comprehensive governance and oversight of efforts to respond to the pay problems. Public Services and Procurement Canada did not work with departments and agencies to define, agree to, and implement accountabilities and responsibilities. There were several committees and working groups at various levels that focused on pay problems. However, there was no governance structure to define which committees and working groups were needed and what their roles and responsibilities should be to provide clear direction, or to coordinate their work.

1.87 In contrast, in Australia, Queensland Health, which had similar problems with a new payroll system, put in place a governance structure and a comprehensive plan to resolve its pay problems within four months of their arising (Exhibit 1.6).

Exhibit 1.6—Case study: Clear governance helped Queensland Health resolve its employee pay problems

In March 2010, Queensland Health, a government department in the Australian State of Queensland, went live with an information technology system to manage the payroll and human resource functions for the department’s 78,000 employees. Soon after the launch, significant errors appeared, and many employees did not receive their correct pay.

Once Queensland Health realized that the problem was significant, it established a clear governance structure, with realistic deliverables and timelines, and cost estimates for the life cycle of the entire project.

Within four months of pay problems arising, Queensland Health developed a comprehensive plan to resolve its pay problems. The plan included multiple process reviews and information technology projects. Queensland Health planned to return to stable short-term pay operations over several months with a budget of CAN$246 million.

Queensland Health also developed a longer-term plan to ensure that all pay problems were resolved. This plan was costed at over CAN$1.0 billion.

In total, the recovery from the payroll system implementation required over 1,000 staff and contractors and over CAN$1.2 billion. Although most of the projects were completed by 2017, issues related to the 2010 implementation continue to be addressed eight years later.

Source: Based on information from Queensland Health, a government department in the Australian State of Queensland

1.88 At the end our audit period, we noted two announcements regarding government-wide efforts to resolve pay problems. First, in April 2017, the Prime Minister announced the creation of a Cabinet-level ministerial working group to take a government-wide approach to addressing pay problems. Second, in June 2017, Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat acknowledged that the governance to manage Phoenix was not sufficient, and together they announced three initiatives:

- A Public Services and Procurement Canada Associate Deputy Minister was named responsible for activities to resolve pay problems, supported by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- A new interdepartmental deputy minister committee was created. It will include representatives from large and small departments and agencies and will provide direction and oversight to the actions needed to resolve pay problems.

- A project management office was created at Public Services and Procurement Canada to resolve pay problems.

1.89 Actions to resolve pay problems. Since July 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada made commitments and produced several plans to resolve pay problems.

1.90 First, in July 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada said it would process what it said were the outstanding pay requests for 82,000 employees by the end of October 2016. When the Department realized that it could not process these requests by 31 October 2016, it said it would process the remaining requests as soon as possible. However, by the end of our audit period, Public Services and Procurement Canada told us that pay requests for 5,000 of these 82,000 employees still had not been processed. As our analysis shows (see paragraph 1.29), there were more than 150,000 employees with outstanding pay requests at the end of our audit period.

1.91 Then, in December 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada publicly announced that pay advisors would focus on pay requests in four priority areas: terminations, leave without pay, disability insurance, and new hires. The priorities changed again in January 2017, to focus on disability and parental leave, which the Department stated was based on a request from unions. The Department committed to meeting its target processing timelines by April 2017 for parental leave and May 2017 for disability leave. In March 2017, the Department reported that it was making significant progress in both of these areas and that it was meeting its target by the end of June 2017. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada’s processing target did not include the time it took departments to get a pay request to the Miramichi Pay Centre. This means that from an employee’s perspective, the time it took to receive the pay was usually more than the number of days specified on the Public Services and Procurement Canada website.

1.92 Public Services and Procurement Canada later said that it would prioritize pay requests that had a high financial impact on employees, which accounted for over half of outstanding pay requests. (The Department defines a high financial impact as over $100 and a low financial impact as up to $100.) Its goal was to process all outstanding high-impact pay requests and meet the processing target for new requests every month by the end of summer 2017. However, we found at the end of our audit that high-impact pay requests still made up more than half the requests and were increasing (Exhibit 1.7).

Exhibit 1.7—Pay requests with high financial impact made up more than half the outstanding pay requests

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 1.7—text version

This bar graph shows the numbers and percentages of outstanding pay requests, grouped according to financial impact, from February to June 2017. More than half of the outstanding pay requests had a high financial impact.

| Month in 2017 | Number of outstanding pay requests with high financial impact (%) | Number of outstanding pay requests with low financial impact (%) | Number of outstanding pay requests with no financial impact (%) | Total number of outstanding pay requests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February | 231,274 (52%) | 172,516 (39%) | 40,295 (9%) | 444,085 |

| March | 233,181 (50%) | 186,439 (40%) | 43,953 (10%) | 463,573 |

| April | 242,042 (50%) | 191,525 (40%) | 47,395 (10%) | 480,962 |

| May | 251,647 (51%) | 190,507 (38%) | 52,494 (11%) | 494,648 |

| June | 258,063 (52%) | 181,689 (37%) | 54,782 (11%) | 494,534 |

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

1.93 In spring and summer 2017, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat agreed to 18 collective agreements with federal public service unions, generally three to four years after the old ones had expired. Public Services and Procurement Canada is responsible for implementing the new agreements’ terms and conditions in Phoenix by fall 2017, so it changed its pay-processing priority again. In June 2017, for those employees covered by the collective agreements, it began to focus on individual employees with multiple outstanding pay requests. Its goal was to process all outstanding pay requests that might affect the implementation of the collective agreements and that must be processed before the retroactive payments from the new collective agreements can be processed. Among the outstanding pay requests, there were a significant number that could not be automatically processed by Phoenix and had to be processed manually. Consequently, Public Services and Procurement Canada hired 65 pay advisors to specifically process these pay requests. At the end of our audit period, the Department transferred an additional 135 pay advisors and staff from the Miramichi Pay Centre to help process collective agreement pay changes in order to meet the fall 2017 deadline.

1.94 Public Services and Procurement Canada’s latest plan to resolve pay problems, prepared in April 2017, included making system and process improvements and working with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and departments to align departmental human resource systems with Phoenix by April 2019. However, we are concerned that Public Services and Procurement Canada did limited consultation with departments and agencies when it developed the plan.

1.95 A major element of Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response was to add pay staff to process the outstanding pay requests. In addition to hiring 65 pay advisors to process collective agreements, the Department

- hired 90 pay advisors at the Miramichi Pay Centre to complement the existing 550 pay advisors and support staff;

- hired 315 pay advisors for new pay offices across the country;

- trained 32 employees, mostly from other departments, to work evening shifts as pay advisors; and

- trained 72 pay advisors in some of the 46 departments and agencies that did not have direct access to Phoenix and gave them access to Phoenix to process pay requests for their departments.

1.96 The Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative was supposed to centralize pay services in Miramichi for the 46 departments and agencies that did not have direct access to Phoenix. By training and giving Phoenix access to pay advisors in these departments and agencies, and by opening new pay offices, Public Services and Procurement Canada has taken, at least temporarily, a decentralized approach to resolving some pay problems.

1.97 Public Services and Procurement Canada’s goal was to reduce the number of outstanding pay requests and process pay requests in an efficient, consistent manner with minimal errors, within a specific timeline. We found that by the end of our audit period, the number of problems and of employees affected by them had continued to grow. This demonstrates that the Department did not have a good understanding of the causes of pay problems or of how best to resolve them.

1.98 Recommendation. Public Services and Procurement Canada, with the support of departments and agencies, should resolve outstanding pay requests as soon as possible, by

- considering all the outstanding pay requests; and

- establishing priorities and setting targets to process all outstanding pay requests, and monitoring and reporting regularly on progress.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Reducing the size of the queue and improving timely and accurate processing of pay requests flowing through the HR-to-pay process remains a critical priority. As part of the HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan, Public Services and Procurement Canada, with the support of departments and agencies, is resolving outstanding pay requests. Public Services and Procurement Canada continues to monitor the inventory of outstanding pay requests and its progress against established priorities and targets. The HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan is comprehensive and will be multi-phased. It is evergreen and will incorporate additional analysis as it becomes available. Oversight on the progress and outcomes of the implementation of the Integrated Plan will be provided by the government-wide Governance Framework. A preliminary HR-to-Pay Integrated Plan for Phase I will be finalized by December 2017.

A sustainable solution will take years and cost much more than the $540 million the government expected to spend to resolve pay problems

1.99 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada as well as departments and agencies expected to spend about $540 million over three years to reach a point where pay requests could be processed in a timely and accurate manner.

1.100 We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada as well as departments and agencies had hired, expected to hire, or reallocated from other duties close to 1,400 employees to resolve the pay problems, at least temporarily. These employees are in addition to the 550 pay staff at the Miramichi Pay Centre. This more than offsets the 1,200 pay advisor positions that were eliminated when pay services were centralized.

1.101 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

1.102 This finding matters because it shows that the effort to get pay processing to the point that it can be done within standard time frames will take a significant amount of money and time.

1.103 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.112.

1.104 What we examined. We examined what costs Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies were incurring to resolve Phoenix pay problems and what future costs were being planned for the longer-term solutions.

1.105 Costs to fix pay problems. We found that there was no centralized process to track what it would cost the government to fix the pay problems. The only department that was required to formally track and report costs was Public Services and Procurement Canada. So we surveyed the remaining departments and agencies on what they spent in the 2016–17 fiscal year and what they planned to spend in the next two fiscal years to resolve Phoenix pay problems.

1.106 Departments and agencies that responded to our survey reported that they spent at least $60 million in the 2016–17 fiscal year and planned to spend about $140 million more between the 2017–18 and 2018–19 fiscal years, mostly to hire more staff. Departments and agencies estimated that they needed a total of at least 820 additional staff, either reallocated from other duties or newly hired, to resolve pay problems. This is in addition to the staff that Public Services and Procurement Canada hired or planned to hire to process pay requests.

1.107 With the additional staff that Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies have hired, planned to hire, or reallocated from other duty, close to 1,400 pay staff will have been added to the 550 pay staff at the Miramichi Pay Centre to help resolve pay problems, at least temporarily. This more than offsets the 1,200 pay advisor positions that were eliminated under the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative.

1.108 In fall 2016 and spring 2017, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat told departments and agencies serviced by the Miramichi Pay Centre that to help them pay for hiring pay advisors, their budgets would not be reduced as planned over three fiscal years. This reduction was supposed to save the government $70 million a year once the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative was implemented.

1.109 As the administrator of the pay system, Public Services and Procurement Canada spent $85 million as of 31 March 2017 and also planned to spend an additional $255 million over the next two years to fix pay problems.

1.110 As of 31 March 2017, Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies had spent at least $145 million on fixing pay problems, and planned to spend at least an additional $395 million over the next two fiscal years, totalling $540 million. This means Public Services and Procurement Canada and departments and agencies will need to keep the $210 million in budget reductions that they were supposed to achieve over the 2016–17 to 2018–19 fiscal years and will need to find an additional $330 million to resolve pay problems.

1.111 We are concerned that those cost estimates did not include the cost to get the pay system to work the way it was supposed to work, so we believe that the cost to have a sustainable system that comes close to its original goals of automating pay and achieving efficiencies would be much higher.

1.112 Recommendation. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, with the support of Public Services and Procurement Canada, and in partnership with departments and agencies, should track and report on the cost of

- resolving pay problems, and

- implementing a sustainable solution for all departments and agencies.

The Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, with the support of Public Services and Procurement Canada, and in partnership with departments and agencies, will establish a cost estimate for the Government of Canada for the Phoenix pay system by the end of May 2018. The cost estimate will consist of costs incurred to date (September 2017), and the design and implementation of a framework to track costs for resolving pay problems and implementing a sustainable solution.

Conclusion

1.113 We concluded that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not identify and resolve pay problems in a sustainable way to ensure that public service employees consistently receive their correct pay, on time.

1.114 Departments and agencies contributed to the problems; however, Public Services and Procurement Canada did not provide them with all the information and support to allow them to resolve pay problems to ensure that their employees consistently receive their correct pay, on time.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the pay operations of the Government of Canada as administered by Public Services and Procurement Canada following the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the pay operations of the Government of Canada complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the Rules of Professional Conduct of Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario and the Code of Values, Ethics and Professional Conduct of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Both the Rules of Professional Conduct and the Code are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether selected departments and agencies resolved pay problems in a sustainable way (that is, effectively and efficiently) to ensure that public service employees consistently received their correct pay, on time.

Scope and approach

We audited the following 12 departments and agencies:

- the Canada School of Public Service,

- the Canadian Security Intelligence Service,

- Correctional Service Canada,

- Employment and Social Development Canada,

- National Defence,

- Natural Resources Canada,

- the Privy Council Office,

- Public Services and Procurement Canada,

- the Royal Canadian Mounted Police,

- Shared Services Canada,

- Statistics Canada, and

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

We examined the legislation, policies, and procedures in place to manage and to support the management of pay operations within all the audited departments and agencies. We also met and interviewed officials in all the audited entities, including at the Public Service Pay Centre in Miramichi.

We analyzed data extracted from the information systems of Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool to identify and compare information related to the processing of pay operations. Although we noted issues with the integrity of data, we found the data sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our analysis.

We surveyed pay staff in Miramichi as well as in the satellite centres set up by Public Services and Procurement Canada to increase the Department’s pay processing capacity. The purpose of the survey was to understand the impact on pay advisors of pay problems after Phoenix was first implemented. We sent 740 questionnaires, and received responses from 480 employees, for a total response rate of approximately 65 percent.

In order to support the Auditor General of Canada’s annual audit opinion on the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the year ended 31 March 2017, a sample of employee pay transactions was examined to determine whether or not pay expenses were presented fairly in the financial statements. We analyzed the same sample to determine the error rate of payments made during each bi-weekly pay period.

We surveyed all departments and agencies whose pay services are processed by Phoenix to gain a better understanding of the financial impact of pay problems after Phoenix was deployed. We sent 87 questionnaires, and received 77 responses, for a total response rate of approximately 89 percent.

We reviewed similar events around the world to get a better understanding of causes and responses. In particular, considering the similarities in the development and implementation of Canada’s pay transformation initiative and the Queensland Health payroll system, we met with Queensland government officials as well as private consulting firms in Brisbane, Australia, to get a better understanding of the nature and impact of problems resulting from the deployment of the Queensland Health payroll system and how these problems were resolved.

We did not examine the events and decisions that led to the implementation of the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative, including the centralization of pay advisors and the launch of Phoenix. The implementation of Phoenix is the focus of a future audit.

Criteria

To determine whether selected departments and agencies resolved pay problems in a sustainable way (that is, effectively and efficiently) to ensure that public service employees consistently received their correct pay, on time, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Problems related to paying public service employees are identified, and the nature and impact of these problems are understood. |

|

|

The resolution of problems related to paying public service employees is being effectively and efficiently managed. |

|

|

Comprehensive and coherent governance and oversight detailing accountabilities and responsibilities for resolving problems related to paying public service employees are defined, agreed to, and implemented. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 24 February 2016 and 30 June 2017. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of the audit.

Date of the report