2018 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 2—Conserving Federal Heritage Properties

2018 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 2—Conserving Federal Heritage Properties

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 2.1—Some heritage buildings that we visited were in good condition

- 2.2—Some heritage buildings that we visited were in poor condition

- 2.3—For the three audited organizations, the number of newly designated buildings increased by a combined total of 68 between 2008 and 2016

- 2.4—Fisheries and Oceans Canada and National Defence conserved their heritage properties only when required for program requirements

Introduction

Background

2.1 Heritage properties—heritage buildings and national historic sites—are important and valued by Canadians. Heritage properties promote and reinforce the country’s cultural identity. They are assets to maintain, value, and conserveDefinition i for present and future generations of Canadians.

2.2 Canada recognizes the importance of conserving its heritage properties in legislation, policies, and guidelines. In addition, Canada committed to the United Nations sustainable development goal that includes efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage.

2.3 In December 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development tabled a report entitled Preserving Canada’s Heritage: The Foundation for Tomorrow. Its numerous recommendations to the federal government included taking stronger actions to preserve Canada’s heritage properties.

2.4 Our office performed two audits on federal heritage properties, in 2003 and 2007.

2.5 In our 2003 audit, we found that federal heritage properties were at risk. National historic sites and heritage buildings were in poor condition, and the government could not conserve them. Canadian Heritage, Parks Canada, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat all agreed with our recommendations. In particular, Canadian Heritage and Parks Canada agreed to strengthen the legal framework to conserve heritage properties. Canadian Heritage also agreed to work with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat to define what type of information to collect and how to appropriately assess and report on the condition of heritage properties.

2.6 In our follow-up audit in 2007, we reported that Parks Canada had not strengthened the legal framework to conserve heritage properties, leaving them still at risk. Although we found that Parks Canada acted to conserve sites that we reported were in poor condition in 2003, other federal organizations were only sporadically conserving heritage properties. We also found that the Treasury Board Heritage Buildings Policy covered only heritage buildings, not national historic sites.

2.7 In our 2007 audit, we concluded that Parks Canada’s conservation efforts since 2003 were not enough to ensure federal organizations conserved heritage properties. We made recommendations to the government, National Defence, Parks Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and Public Works and Government Services Canada (name changed to Public Services and Procurement Canada). The government agreed that the conservation regime should be strengthened, and National Defence, Parks Canada, and Public Works and Government Services Canada agreed to establish conservation objectives to conserve their federal heritage properties.

2.8 In this audit, we examined Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence, which together own over 70% of all federal buildings with heritage designationDefinition ii. As of 2017, the federal government owned 1,272 designated buildings and at least 223 national historic sites across Canada.

2.9 Parks Canada. Parks Canada is the lead federal organization for programs to conserve federal heritage properties. Parks Canada told us that it owns and manages 171 national historic sites and 504 heritage buildings. The Agency is also responsible for implementing Government of Canada policies on

- national parks,

- national historic sites,

- national marine conservation areas,

- other federally protected heritage areas, and

- heritage protection programs.

2.10 Parks Canada also supports the administration of the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act, introduced in 2010. The Act’s purpose is to conserve lighthouses through their heritage designation and to facilitate the sale or transfer of heritage lighthouses to individuals and communities. Once designated, heritage lighthouses must be well maintained.

2.11 In 2006, the government introduced the Treasury Board Policy on Management of Real Property. It requires federal organizations to have Parks Canada evaluate all federal buildings over 40 years old for their heritage character. On the basis of that evaluation, Parks Canada recommends to the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change (who is responsible for Parks Canada) whether these buildings should be designated.

2.12 Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Fisheries and Oceans Canada manages Canada’s fisheries and safeguards the country’s waters. The Department told us that it has 267 heritage buildings, including 32 heritage lighthouses designated under the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act. Fisheries and Oceans Canada owns most federally owned lighthouses and told us that it has 7 national historic sites.

2.13 National Defence. National Defence owns 292 heritage buildings and 22 national historic sites across the country. Examples include armouries and airplane hangars.

Focus of the audit

2.14 This audit focused on whether Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence worked to conserve the heritage value and extend the life of federal heritage properties for present and future generations of Canadians to enjoy. The audit focused on national historic sites and heritage buildings, including heritage lighthouses.

2.15 This audit is important because there are long-standing problems in the conservation of federal heritage properties, with few improvements since our first audit in 2003. Past efforts to conserve federal heritage properties have not kept up with needs, yet the number of federal heritage buildings continues to grow. This means that the loss of valuable heritage properties will likely increase.

2.16 We did not examine the processes to designate a building as heritage or to determine a national historic site.

2.17 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

2.18 Overall, we found that Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence did not do enough to conserve the physical condition and heritage value of federal heritage properties. The three audited organizations either did not know how many heritage buildings they had or did not know what condition the buildings were in. Also, the heritage property information the organizations provided to Parliament and the public was inaccurate or incomplete.

2.19 Designation as a heritage property does not include additional funding for conservation work. As a result, the three organizations prioritized the heritage buildings to conserve on the basis of available resources and operational requirements, rather than heritage considerations.

2.20 In addition, the number of designated heritage buildings increased. However, because of the lack of additional funding for conservation work, more buildings may fall into disrepair. This means that present and future generations of Canadians could lose an important part of their country’s history.

Condition of heritage properties

The organizations that we examined did not have a full picture of their heritage properties, but we saw many that were deteriorating

2.21 We found that Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence’s asset management databases did not have up-to-date information on the condition of the organizations’ heritage buildings. In addition, Parks Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not have accurate information on the number of all their heritage buildings. As a result, these organizations did not have a full picture of their heritage properties and therefore lacked complete information for decision making. We found, however, that the regional representatives we met knew the number and condition of the heritage properties that they were responsible for.

2.22 Because we could not rely on the data in the organizations’ databases, we could not put together an accurate overview of the condition of federally owned heritage buildings and national historic sites. Nevertheless, we saw many that were deteriorating during our visits to buildings and sites.

2.23 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Number of heritage buildings

- Condition of heritage buildings

- Reporting to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

2.24 This finding matters because reliable data gives federal organizations a full picture of their heritage properties so that they may plan and prioritize conservation activities. Reliable data also provides the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat with updated information on properties for its public directory.

2.25 Each federal organization has an asset management database with information on its buildings, including its heritage buildings. This information is also used to update the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Directory of Federal Real Property, which lists basic information on the Government of Canada’s property. This directory is the federal public database with information on the condition of buildings across 71 custodian organizations.

2.26 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.36.

2.27 What we examined. We examined whether the organizations that we audited knew how many heritage properties they had and what condition the properties were in. We examined data on heritage buildings in each organization’s asset management database. To get a better sense of the condition of heritage properties, we visited selected sites and buildings across Canada.

2.28 Number of heritage buildings. We found that, despite its lead role for federal heritage conservation programs, Parks Canada had an asset management database that did not indicate all of its heritage buildings. We found that the database identified only 186 heritage buildings. The Agency took over four weeks to provide us with what it said was the complete list of 504 heritage buildings.

2.29 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s database did not have accurate information on which lighthouses were designated under the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act. For example, the database contained lighthouses that the Department no longer owned, as well as those that were not designated as heritage under the Act but were shown as being so in the database.

2.30 For National Defence, on the other hand, we found that its data on the number of heritage buildings was complete and that its database indicated which buildings were designated as heritage.

2.31 Condition of heritage buildings. We found that the three organizations that we audited did not have a full picture of the condition of their heritage buildings. We examined examples of buildings in Parks Canada’s asset management database but could not confirm whether the information on their condition was accurate. For example, documentation on the condition did not always match the condition stated in the database. In other cases, there was no source documentation to support the condition claimed in the database.

2.32 We found that information on the condition of heritage buildings in National Defence’s and Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s databases was not current or supported by source documents. National Defence data was based on assessments completed in the 2009–10 fiscal year. Although National Defence recently completed condition assessments for 214 of its 292 heritage buildings, this information was not in the database at the time of the audit. We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada updated assessments for only 7 of 267 heritage buildings in 2017. If Fisheries and Oceans Canada continues to update 7 assessments a year, it will take over 30 years to complete all assessments.

2.33 To get a better sense of the condition of heritage properties, we visited 47 buildings at 19 locations in British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia. The types of properties included lighthouses, hangars, residences, and armouries. We saw some buildings that in our opinion were in relatively good condition (Exhibit 2.1), but we saw an equal number of buildings in poor condition (Exhibit 2.2). Some buildings had crumbling bricks, no roofs, and graffiti, and some were in danger of collapse. We saw buildings in such bad condition that in our opinion, they were health and safety risks. Two of those buildings were directly accessible to the public, and others were easily accessible despite barricades or signs intended to restrict access.

Exhibit 2.1—Some heritage buildings that we visited were in good condition

Dockyard Main Office at Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt, British Columbia

National Defence’s Dockyard Main Office building is a good example of the classically inspired design of federal buildings during the 1930s. The building was originally constructed as an administration and command centre in 1937. In 2017, National Defence completed upgrades to protect the building from earthquakes and meet the building code, including for accessibility. The Department continues to use the building for office space.

Murney Martello Tower in Kingston, Ontario

Built in 1846, the Murney Martello Tower was part of the defence system built for the Kingston Harbour, in response to border disputes between British North America and the United States in the 1840s. Parks Canada’s conservation work in 1995 included major stabilization and subsequent repairs to the roof and masonry. Open to the public, the tower has three floors displaying military and domestic artifacts from the 19th century.

Prince of Wales Tower in Halifax, Nova Scotia

Built between 1796 and 1799, the Prince of Wales Tower was the first of its type in North America. It was used as a place to store gunpowder and as a redoubt to protect soldiers outside the main defensive line. Parks Canada took steps in 2016 to help stop the deterioration, including refitting the tower with a new roof over the existing roof to prevent water infiltration.

Photos: Office of the Auditor General of Canada

Exhibit 2.2—Some heritage buildings that we visited were in poor condition

York Redoubt National Historic Site in Halifax, Nova Scotia

York Redoubt is a 200-year-old fortification to the west of Halifax Harbour. It has helped to protect the port for centuries and includes a command centre for harbour defences during the Second World War. Although Parks Canada barricaded access with a gate and fencing, we found that individuals still easily accessed the site and marked it with graffiti.

Louis-Joseph Papineau House in Montréal, Quebec

Built in 1785 and located in Old Montréal, this house was designated not only for its connection with a historic figure, but also for its architectural characteristics. Over the past 10 years, Parks Canada completed some work on the building, such as repairs to the roof and chimney. However, significant masonry repairs are still needed, as well as major work to the interior of the house. Funds have been allocated to begin conservation work.

Hangar 13 at Canadian Forces Base Borden, Ontario

Hangar 13 was a temporary structure built in 1917 to store aircraft during the First World War. Since National Defence no longer needed it for program requirements, the Department has allocated no money to conserve it. Because loose debris and building material posed a health and safety risk, National Defence wrapped the hangar in vinyl tarps in 2016.

Superintendent’s Residence in Carillon, Quebec

Built between 1842 and 1843, the Superintendent’s Residence, owned by Parks Canada, is a rare surviving example of the Carillon Canal’s military and commercial role. Located next to the canal, the building is valued for its good aesthetic and functional design. We found the residence to be in poor condition, with crumbling foundations, rotting wood, and deteriorating stone walls—and no notices to warn people. Despite the poor condition, the residence was not fenced off, and health and safety concerns prevented us from entering the building.

Photos: Office of the Auditor General of Canada

2.34 We examined the data in the three organizations’ databases so that we could report on the overall condition of the organizations’ heritage buildings. However, we found that we could not rely on this data because it was incorrect or the building condition assessments were out of date. Since we could not rely on this data, we could not get a comprehensive picture of the condition of the properties that we did not visit. This also means that none of the three organizations could know the overall condition of their heritage properties.

2.35 Reporting to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Federal policy requires federal organizations, as defined in the Financial Administration Act, to maintain current, complete, and accurate records of their inventories in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Directory of Federal Real Property. Annually, each organization must certify the completeness and accuracy of its records in the directory. We found that some of the directory information provided by the organizations that we audited was inaccurate, despite their certifications. Condition information was not up to date for some National Defence and Parks Canada properties, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada reported continued ownership of lighthouses that it no longer owned.

2.36 Recommendation. Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence should update their asset management databases to reflect complete information on the number and current condition of their heritage properties.

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada will complete the identification of the federal heritage properties under its responsibility and will indicate the condition of these properties in the appropriate asset or land management system. This will allow for the up-to-date accounting of the heritage assets under Parks Canada’s responsibility. This action should be completed by the fall of 2019.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada recognizes that its property management database (the Real Property Information Management System) does not consistently identify all heritage assets under one of the three designation methodologies: the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, the Federal Heritage Buildings Review Office, or the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act.

Given the complexity of the portfolio and resource constraints, the Department was unable to update the background and heritage-related information in the required time. However, we are updating our real property databases in a systematic manner, prioritizing sites that support program requirements.

Following Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s successful comprehensive review submission to the Treasury Board, the Department’s Real Property Services has placed a high priority on improving the quality of its real property information. Significant progress has been made to date, including the staffing of additional dedicated information management resources, nationally and regionally, as well as validating and cleansing existing data. The process involves the review of over 6,600 Fisheries and Oceans Canada assets. Moving forward, this information will continue to be updated on a cyclical basis.

Implementation is currently under way with completion expected by the end of the 2020–21 fiscal year.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence’s real property database, the Defence Resource Management Information System, indicates which buildings are heritage properties. National Defence will work within this system by loading the new condition assessment data obtained between 2016 and 2018 for all buildings, including 214 of 292 heritage buildings. This data will be loaded by December 2018 and will be part of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Directory of Federal Real Property submission for certification in December 2018. National Defence will continue to gather data on the condition of its heritage assets with the objective of assessing the condition of 20% of the real property heritage portfolio each year.

Conservation of heritage properties

Parks Canada could not conserve all of its heritage properties

2.37 We found that the federal government focused primarily on designating heritage properties, rather than conserving them. Federal policies and legislation provided processes and authorities primarily to designate heritage properties, but these designations did not come with conservation funding. For example, the money earmarked for conserving heritage properties owned by Parks Canada fell far short of the amount of conservation work identified in the Agency’s backlog.

2.38 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Parks Canada’s conservation of its own properties

- Parks Canada’s conservation activities as lead organization

2.39 This finding matters because designating a federal property as heritage includes a responsibility to conserve it. Conserving a property requires funding.

2.40 Parks Canada is responsible for providing professional and administrative services to commemorateDefinition iii places of national historic significance and to conserve heritage railway stations and heritage lighthouses. In addition, the Agency provides standards and guidelines to other federal organizations on conservation. However, Parks Canada is responsible for conservation activities only on heritage property in its own portfolio.

2.41 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.62.

2.42 What we examined. We examined whether the processes in place helped to conserve federal heritage properties, or whether the processes primarily designated them. We also examined Parks Canada’s activities in relation to requirements and guidelines to direct conservation.

2.43 Parks Canada’s conservation of its own properties. Parks Canada’s policy states that the Agency must conserve its cultural resources to share with present and future generations. The policy also states that the Agency must consider available financial and human resources when making conservation decisions. We found that the Agency set priorities on the basis of available resources to determine which properties were to be maintained, conserved, and monitored regularly. Key considerations to determine priorities can include whether there are similar resources elsewhere and the risk of not intervening, including property deterioration.

2.44 According to Parks Canada, it invested $50.5 million between 2015 and 2018 to maintain and conserve heritage properties. This amount included one-time funding to reduce the backlog of deferred conservation work required. However, the Agency acknowledged that it could not conserve all its heritage properties and reported that its deferred maintenance backlog on federal heritage properties was $1.2 billion in 2017.

2.45 Parks Canada’s conservation activities as lead organization. Although Parks Canada was the federal government’s lead for programs to conserve heritage properties, we found that its role was primarily limited to recommending heritage property designation for approval by the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change and giving conservation guidance when consulted, including to other federal organizations.

2.46 We found that once the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change designated buildings under the Treasury Board Policy on Management of Real Property, there was no additional regular funding for departments and agencies to conserve the buildings. Parks Canada could provide conservation advice, but could not compel departments and agencies to follow its advice or to do any conservation or maintenance work in order to protect designated buildings.

2.47 We also found that when federal lighthouses were designated as heritage under the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act, there was no additional regular funding for lighthouse owners to conserve them. However, the Act gave the federal government authority to impose conservation requirements on the owners of designated lighthouses, whether the owners were federal departments or other third parties. For example, a purchase agreement between the federal government and a third party buying a designated lighthouse had to include a written commitment to conserve the lighthouse. This agreement resulted in owners of designated lighthouses, including third parties, having to meet higher conservation expectations than those placed on federal organizations for the conservation of other designated federal buildings.

2.48 We found that Parks Canada encouraged other federal organizations to prioritize conservation of their heritage properties on the basis of their available resources, thereby acknowledging that not all heritage properties could be conserved.

National Defence and Fisheries and Oceans Canada based their conservation decisions on program requirements, not heritage considerations

2.49 We found that National Defence and Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not earmark money specifically for conserving heritage properties. The departments did not differentiate between their heritage properties and their other properties. Therefore, they made maintenance decisions on the basis of program requirements, rather than heritage value.

2.50 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

2.51 This finding matters because many federal organizations own heritage properties that need to be conserved.

2.52 Federal organizations, as defined in the Financial Administration Act, must follow the Treasury Board Policy on Management of Real Property. Therefore, they must submit buildings 40 years or older to be evaluated and considered for heritage designation. However, the policy also requires organizations to keep only those heritage properties needed for program requirements.

2.53 The Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act allowed Fisheries and Oceans Canada to indicate which lighthouses were surplus to operational requirements. Surplus lighthouses could be designated if a third party (such as a community group) commits to acquiring the lighthouse and protecting its heritage character.

2.54 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.62.

2.55 What we examined. We examined whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada and National Defence conserved their heritage buildings and national historic sites according to their obligations for managing their properties.

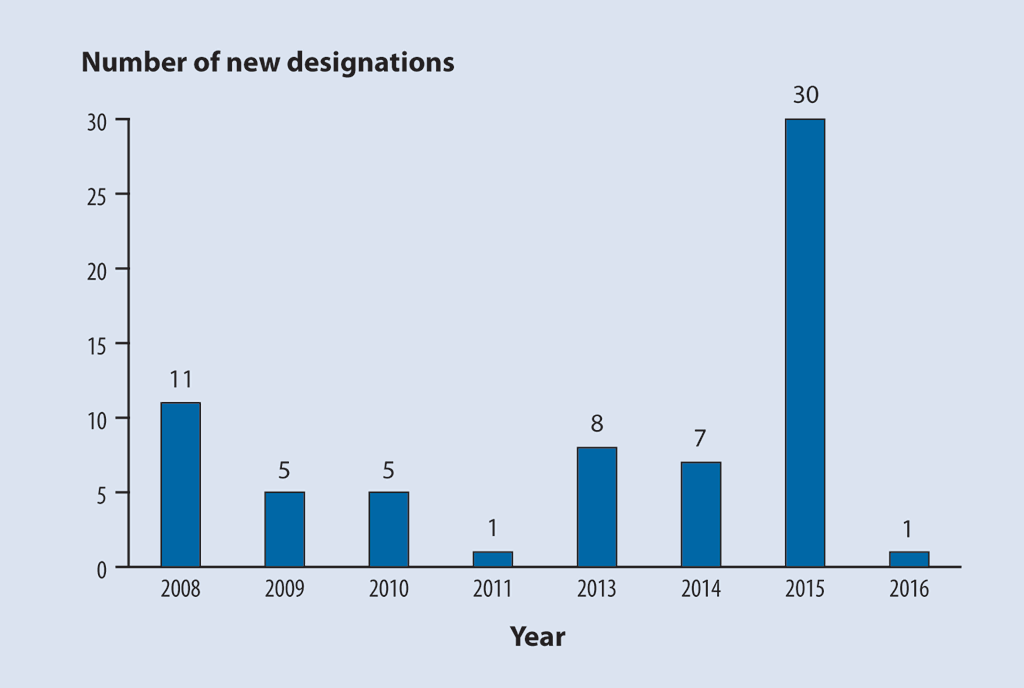

2.56 Motivation for the departments to conserve heritage properties. As required by policy, buildings 40 years or older undergo a designation evaluation. Because heritage designations never expire if they remain under federal control, the number of federal heritage buildings continues to grow (Exhibit 2.3).

Exhibit 2.3—For the three audited organizations, the number of newly designated buildings increased by a combined total of 68 between 2008 and 2016

Source: Parks Canada (data unaudited)

Exhibit 2.3—text version

This bar graph shows that for the three audited organizations—Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence—the number of newly designated heritage buildings increased by a combined total of 68 between 2008 and 2016.

- In 2008, there were 11 new designations.

- In 2009, there were 5 new designations.

- In 2010, there were 5 new designations.

- In 2011, there was 1 new designation.

- In 2013, there were 8 new designations.

- In 2014, there were 7 new designations.

- In 2015, there were 30 new designations.

- In 2016, there was 1 new designation.

Source: Parks Canada (data unaudited)

2.57 However, we found that once properties were designated, the organizations were not given funds to conserve them. As a result, heritage properties risked continual deterioration.

2.58 Because federal policy required organizations to keep only heritage buildings needed for program requirements, we found that the organizations had little motivation to conserve all their heritage properties. Each department managed its heritage properties on the basis of its own resources and priorities.

2.59 During the audit period, Fisheries and Oceans Canada told us that it owned 32 lighthouses designated under the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act. We found that not all were being conserved despite the Act’s conservation requirements (Exhibit 2.4).

Exhibit 2.4—Fisheries and Oceans Canada and National Defence conserved their heritage properties only when required for program requirements

Photo: Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Green Island Lighthouse in Catalina, Newfoundland and Labrador

Located on Green Island at the southern entrance to Catalina Harbour, the Green Island Lighthouse, also known as Catalina Lighthouse, is a concrete tower built from 1856 to 1857. It is an example of the navigational aids used in early colonial Newfoundland.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada stated that the lighthouse is in poor condition and unsafe for staff to enter. Concrete is splitting, and pieces have fallen from the structure.

Because it was no longer required for operations, the navigational light was relocated to an automated freestanding tower nearby.

Photo: Office of the Auditor General of Canada

Halifax Armoury in Halifax, Nova Scotia

Constructed between 1895 and 1899, the Halifax Armoury is valued for its characteristic trusses, which allowed the large interior space to be free of columns and walls. Its heritage value is also associated with late 19th-century federal government initiatives to build militia practice, training, and recruitment centres. National Defence uses the Armoury to meet operational requirements of Army reserve units and cadet corps. A two-phase, $130 million conservation project is currently under way to conserve the Armoury to meet program needs.

2.60 We found that National Defence also prioritized maintenance decisions on the basis of operational requirements. This maintenance included the conservation of heritage properties. In addition to the Department’s regular funding, in 2014, the Department received one-time funding of $452 million to maintain and repair properties, of which $72.3 million was allocated by the Department to heritage properties. The Department used this money primarily to help conserve operational armouries across the country (Exhibit 2.4).

2.61 We noted that there was no link between designation and conservation. Although the number of designated buildings continued to increase (Exhibit 2.3), there were no additional resources to conserve the buildings. Moreover, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and National Defence prioritized program requirements over conservation—an approach that cannot sustain the conservation of federal heritage properties.

2.62 Recommendation. Parks Canada should lead an assessment of the approach to designate and conserve federal heritage properties. Working with organizations that own properties, it should implement changes to better conserve heritage properties.

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada will assess, in consultation with custodian departments, the current approach to designate federal heritage buildings. This assessment is expected to be completed by the fall of 2019.

The Agency will review, in consultation with custodian departments, the implementation of changes to better conserve federal heritage buildings. This review should be completed by the fall of 2020.

Information to Canadians and parliamentarians

Canadians and parliamentarians received inadequate information on heritage properties

2.63 We found that information for the public and parliamentarians on heritage properties was inconsistent, inaccurate, incomplete, and out of date.

2.64 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

2.65 This finding matters because complete and current information allows Canadians and parliamentarians to fully understand and discuss the condition of heritage properties and the potential consequences of not conserving them.

2.66 Canadians can access information on heritage properties in two public Parks Canada databases:

- the Directory of Federal Heritage Designations, and

- the Canadian Register of Historic Places.

2.67 Another public database, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Directory of Federal Real Property, is intended to hold information on all federal land and buildings of organizations defined in the Financial Administration Act. This directory includes heritage buildings, although heritage buildings are not identified as such in the database. This directory is also the only public federal database that provides information on asset condition.

2.68 To get a full picture of a federal heritage property, an individual would need to know whether a property is heritage, consult one of Parks Canada’s databases to obtain heritage information, and then consult the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Directory of Federal Real Property for condition information.

2.69 Parks Canada is required to report at least every five years to Parliament on the condition of national historic sites and heritage conservation programs.

2.70 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.75.

2.71 What we examined. We examined whether Canadians and parliamentarians received up-to-date and accurate information about federal heritage properties. We reviewed the two Parks Canada databases that the public can access for information on federal heritage buildings.

2.72 Public information on heritage properties. We found problems when comparing the information in the two Parks Canada public databases on heritage properties:

- Text describing the same building did not always match in both databases.

- Building descriptions were sometimes incomplete.

- Buildings listed in one database were not always listed in the other.

- The same photograph was used for two different buildings in two different locations.

- Some photographs were historic and did not show the current condition of buildings.

- Some entries had blank pages or were missing content.

2.73 Reporting to Parliament. According to the Parks Canada Agency Act, Parks Canada must report to Parliament at least every five years, including on the condition of national historic sites and heritage conservation programs. We found that although Parks Canada did report to Parliament in 2011 and in 2016 on the condition of national historic sites the Agency owns, these reports were incomplete. Reports were missing information on the condition of some historic sites and did not contain information on the condition of the Agency’s designated buildings.

2.74 Parks Canada is also required to submit a management plan for each national historic site to the House of Commons at least every 10 years. We found that these plans were available on the Parks Canada website and included information on the condition of the historic site. But we also found that 39 plans were older than 10 years, and that 87 historic sites did not have a management plan at all.

2.75 Recommendation. Parks Canada should provide accurate and up-to-date information to Canadians and parliamentarians through public databases and reports to Parliament.

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada will first complete the action described in the Agency’s response to the recommendation at paragraph 2.36. The Agency will then review how to make this information available to the public. This action should be completed by the fall of 2020. This information will be used in reports to Parliament.

Conclusion

2.76 We concluded that Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence did not work sufficiently to conserve the heritage value and extend the physical life of federal heritage properties. They did not have a full picture of their heritage properties; for example, information on the condition of their heritage properties was not current.

2.77 The life of some federal properties was at risk—properties that are for the enjoyment of present and future generations of Canadians. Heritage property designation included no additional funding to conserve buildings. Information to the public and to parliamentarians was also inadequate.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the conservation of federal heritage properties. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the conservation of federal heritage properties complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Parks Canada and selected departments were working to conserve the heritage value and extend the physical life of federal heritage buildings and national historic sites for the enjoyment of present and future generations of Canadians.

Scope and approach

The federal organizations audited were Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence. Parks Canada is the lead federal organization for programs to conserve federal heritage properties, and the three organizations own over 70% of all federal buildings with heritage designation.

The audit focused on national historic sites and heritage buildings owned by the three organizations, including heritage lighthouses.

The audit approach included document review and interviews with organization officials at headquarters and in selected regions. The audit team also conducted site visits in those regions. In addition, the team reviewed the heritage buildings found in each organization’s asset management database. The team completed one test on accuracy of condition information in Parks Canada’s database. The test was performed on the basis of targeted sampling. The team selected the items to test on the basis of buildings visited during the site visits.

Criteria

To determine whether Parks Canada and selected departments were working to conserve the heritage value and extend the physical life of federal heritage buildings and national historic sites for the enjoyment of present and future generations of Canadians, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Parks Canada and selected entities have policies, standards, and guidance designed to conserve the heritage value and extend the physical life of designated federal buildings and historic places, and to provide Canadians with timely and accurate information on the assets. |

|

|

Parks Canada and selected entities conserve their federal heritage buildings and historic places, and provide Canadians with timely and accurate information on the assets. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 April 2016 and 30 June 2018. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 14 September 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Jean Goulet

Director: Susan Gomez

Sébastien Defoy

Jocelyn Lefèvre

Hélène Lévesque

Alexandra MacDonald

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Condition of heritage properties

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.36 Parks Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and National Defence should update their asset management databases to reflect complete information on the number and current condition of their heritage properties. (2.21 to 2.35) |

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada will complete the identification of the federal heritage properties under its responsibility and will indicate the condition of these properties in the appropriate asset or land management system. This will allow for the up-to-date accounting of the heritage assets under Parks Canada’s responsibility. This action should be completed by the fall of 2019. Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada recognizes that its property management database (the Real Property Information Management System) does not consistently identify all heritage assets under one of the three designation methodologies: the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, the Federal Heritage Buildings Review Office, or the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act. Given the complexity of the portfolio and resource constraints, the Department was unable to update the background and heritage-related information in the required time. However, we are updating our real property databases in a systematic manner, prioritizing sites that support program requirements. Following Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s successful comprehensive review submission to the Treasury Board, the Department’s Real Property Services has placed a high priority on improving the quality of its real property information. Significant progress has been made to date, including the staffing of additional dedicated information management resources, nationally and regionally, as well as validating and cleansing existing data. The process involves the review of over 6,600 Fisheries and Oceans Canada assets. Moving forward, this information will continue to be updated on a cyclical basis. Implementation is currently under way with completion expected by the end of the 2020–21 fiscal year. National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence’s real property database, the Defence Resource Management Information System, indicates which buildings are heritage properties. National Defence will work within this system by loading the new condition assessment data obtained between 2016 and 2018 for all buildings, including 214 of 292 heritage buildings. This data will be loaded by December 2018 and will be part of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Directory of Federal Real Property submission for certification in December 2018. National Defence will continue to gather data on the condition of its heritage assets with the objective of assessing the condition of 20% of the real property heritage portfolio each year. |

Conservation of heritage properties

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.62 Parks Canada should lead an assessment of the approach to designate and conserve federal heritage properties. Working with organizations that own properties, it should implement changes to better conserve heritage properties. (2.37 to 2.61) |

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada will assess, in consultation with custodian departments, the current approach to designate federal heritage buildings. This assessment is expected to be completed by the fall of 2019. The Agency will review, in consultation with custodian departments, the implementation of changes to better conserve federal heritage buildings. This review should be completed by the fall of 2020. |

Information to Canadians and parliamentarians

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.75 Parks Canada should provide accurate and up-to-date information to Canadians and parliamentarians through public databases and reports to Parliament. (2.63 to 2.74) |

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada will first complete the action described in the Agency’s response to the recommendation at paragraph 2.36. The Agency will then review how to make this information available to the public. This action should be completed by the fall of 2020. This information will be used in reports to Parliament. |