2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 12—Protecting Canada’s Food System

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Designing the emergency food programming

- The government had no national emergency preparedness and response plan for Canada’s food system

- Departments and agencies expedited the design and development of the emergency food programming we examined

- The contributions of the emergency programming to sustainable development and gender and diversity outcomes were not always measured

- Some inconsistencies in program design led to unfairness for applicants and recipients

- Delivering the emergency food programming

- Achieving and reporting on results

- Designing the emergency food programming

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 12.1—Key elements of Canada’s food system and the initiatives we examined to support them

- 12.2—The programs we examined that address food processing and food insecurity issues

- 12.3—Locations of the 121 communities eligible for the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program

- 12.4—The federal departments and agencies we examined did not always establish performance indicators to measure the contributions of the initiatives to sustainable development

- 12.5—The responsible departments and agencies we examined largely met their standards for making funding decisions

- 12.6—The Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund could not provide reliable data on some results

- 12.7—There were weaknesses with the measurement of results for Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s 3 emergency food programs

- 12.8—Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada had Nutrition North Canada data to demonstrate increases in food accessibility in remote and isolated communities

- 12.9—The amount of eligible food items subsidized at medium and high rates that were shipped under the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program increased during the COVID‑19 pandemic

- 12.10—CrownIndigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada did not collect pre‑subsidy pricing information under the Nutrition North Canada program

- 12.11—When data was available, the effect of the Nutrition North Canada subsidy on food affordability could be demonstrated, according to several examples

Introduction

Background

12.1 When the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1 pandemic emerged in Canada in early 2020, it threatened the health of Canadians directly through infection. It also disrupted Canada’s food system. For example, outbreaks in food production and processing facilities reduced or stopped production. The unemployment and loss of wages during the crisis also led to an increased risk of food insecurityDefinition 2, especially among vulnerable populations.

12.2 According to a May 2020 study by Statistics Canada, food insecurity among Canadians rose during the COVID‑19 pandemic to 14.6% (almost 4.4 million people), up from 10.5% (almost 3.1 million people) according to a 2017–18 survey. The May 2020 study also noted that the level of food insecurity for households with children was even higher, at 19.2%, and reached 28.4% for those absent from work because of business closures, layoffs, or personal circumstances as a result of the pandemic.

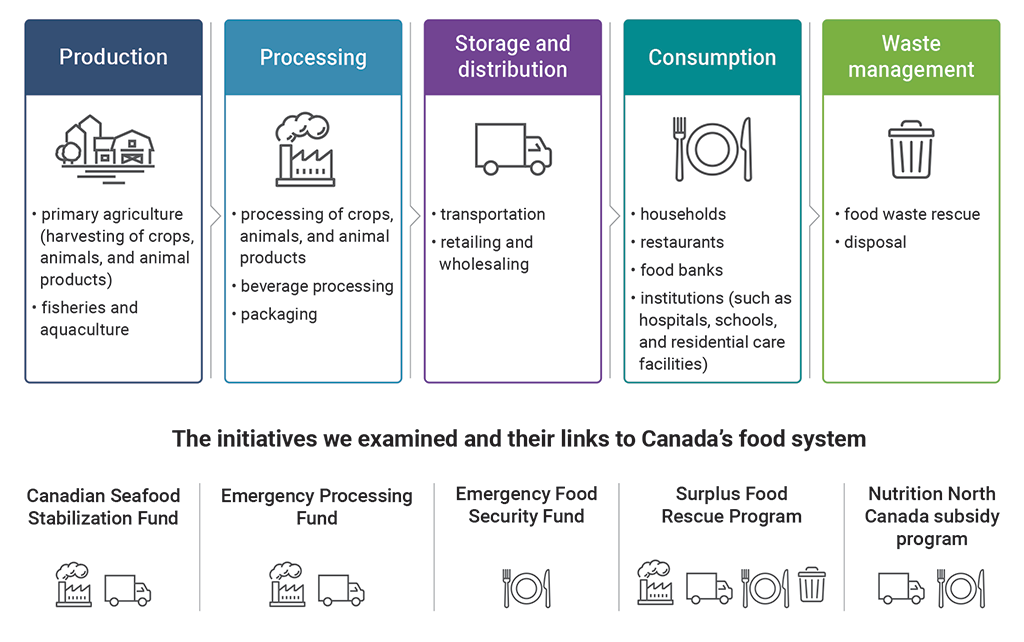

12.3 As part of its broad response to the pandemic, the Government of Canada announced a wide range of new programs along with additional funding to existing programs. Among these, we examined 3 initiatives aimed at reducing food insecurity for Canadians, including in vulnerable and isolated communities, and 2 initiatives aimed at supporting the resilience of Canada’s food-processing capacity. Together, these 5 initiatives involved each element of the food system, except for production (Exhibit 12.1).

Exhibit 12.1—Key elements of Canada’s food system and the initiatives we examined to support them

Source: Adapted from various public sources

Exhibit 12.1—text version

This graphic shows key elements of Canada’s food system along with the initiatives we examined and the initiatives’ links to Canada’s food system.

The 5 key elements of Canada’s food system are as follows:

- production, which involves primary agriculture (harvesting of crops, animals, and animal products) and fisheries and aquaculture.

- processing, which involves the processing of crops, animals, and animal products; beverage processing; and packaging.

- storage and distribution, which involves transportation, and retailing and wholesaling.

- consumption, which involves households, restaurants, food banks, and institutions (such as hospitals, schools, and residential care facilities).

- waste management, which involves food waste rescue and disposal.

The 5 initiatives that we examined and their links to Canada’s food system are as follows:

- the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, which is linked to processing and to storage and distribution

- the Emergency Processing Fund, which is linked to processing and to storage and distribution

- the Emergency Food Security Fund, which is linked to consumption

- the Surplus Food Rescue Program, which is linked to processing, to storage and distribution, to consumption, and to waste management

- the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program, which is linked to storage and distribution and to consumption

12.4 The federal government recognizes the importance of food systems to Canadians’ well-being. According to the Food Policy for Canada, published in 2019, “Food systems, including the way food is produced, processed, distributed, consumed, and disposed of, have direct impacts on the lives of Canadians. Food systems are interconnected and are integral to the wellbeing of communities, including northern and Indigenous communities, public health, environmental sustainability, and the strength of the economy.”

12.5 Moreover, the National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure, published in 2009, had already classified food as 1 of 10 critical infrastructure sectors that are “essential to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government.” On 2 April 2020, the government reinforced the critical importance of the food sector when it released its Guidance on Essential Services and Functions in Canada During the COVID‑19 Pandemic, which identified food services and functions as essential to protect during the pandemic.

12.6 Four of the initiatives we examined were created in 2020 in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, while the fifth program, in place since 2011, received additional funding in 2020 (Exhibit 12.2).

Exhibit 12.2—The programs we examined that address food processing and food insecurity issues

| Program or initiative | COVID‑19-related support |

|---|---|

|

Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund—New funding for the fish and seafood processing sector to help put in place safety measures for workers and to adapt plant operations and storage capacity to respond to changing consumer demands as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Responsible department: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, supported by 3 regional development agencies:

|

$62.5 million total |

|

Emergency Processing Fund—New funding for food processors in the agriculture and agri-food sector to help them maintain and increase domestic food production and processing. Responsible department: Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada |

$77.5 million |

|

Emergency Food Security Fund—New funding for Canadian food banks, food rescue organizations, and other assistance providers to improve access to food for people experiencing food insecurity. Responsible department: Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada |

$300 million |

|

Surplus Food Rescue Program—New funding for organizations addressing food insecurity to help them manage and redirect food surpluses and to avoid food waste. Responsible department: Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada |

$50 million |

|

Nutrition North Canada—Additional funding for an existing program to further subsidize food in remote and isolated northern communities. Responsible department: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

$25 million |

12.7 Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund. This initiative aimed to help fish and seafood processors adapt to the pandemic and put in place measures to keep their workers safe. The initiative was directed at fish, seafood, and aquaculture processing businesses as well as not‑for‑profit organizations that supported the seafood processing sector. The program provided funding to recipients to

- increase their storage capacity to keep unsold or excess fish and seafood from spoiling

- implement health and safety measures and modifications in the workplace

- develop new products or market strategies, or adapt existing products to changing market conditions

12.8 Emergency Processing Fund. This initiative offered funding to help companies

- safeguard the health and safety of workers and their families by supporting projects that responded to emergency needs, to maintain operational capacity and avoid prolonged closures

- improve, automate, and modernize facilities needed to increase Canada’s food supply

12.9 Emergency Food Security Fund. This initiative provided funding to not‑for‑profit organizations that were required to have national networks, a demonstrated administrative capacity, and a focus on food security. These organizations were then required to either use the funds or redistribute them to local food organizations, for activities such as purchasing food, buying or renting equipment, transporting food, and hiring workers.

12.10 Surplus Food Rescue Program. This program provided funding to not‑for‑profit and for-profit organizations to help them manage and redirect food surpluses that might otherwise spoil, go to waste, or fail to reach people facing food insecurity. The program’s funding allowed these organizations to bid on surplus products at or below the cost of production. The organizations could then either process the food into less-perishable forms (for example, by canning or freezing it) or distribute the products to agencies that were working to reduce food insecurity, to ensure that the food would reach vulnerable populations.

12.11 Nutrition North Canada. First launched in 2011, this program subsidizes 78 food commodities (along with 13 non-food items) in 121 eligible communities in the 3 territories (Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut) and in northern Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador (Exhibit 12.3). Food in these more remote and isolated communities is expensive, mainly because of the costs of shipping. Participating retailers in these communities apply the subsidies to reduce the cost to consumers. In response to the pandemic, the program received an additional $25 million to make food and other essential items more accessible and affordable in the eligible communities.

Exhibit 12.3—Locations of the 121 communities eligible for the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program

Note: There are 121 isolated and remote communities that are eligible for the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program, as of 3 August 2021.

Source: Adapted from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

Exhibit 12.3—text version

This map shows the locations of the 121 communities eligible for the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program.

These communities are located in Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

The 1 eligible community in Yukon is Old Crow.

The 19 eligible communities in the Northwest Territories are Aklavik, Colville Lake, Deline, Fort Good Hope, Fort McPherson, Gametì (Rae Lakes), Inuvik, Lutsel K’e, Nahanni Butte, Norman Wells, Paulatuk, Sachs Harbour, Sambaa K'e (Trout Lake), Tsiigehtchic, Tuktoyaktuk, Tulita, Ulukhaktok (Holman), Wekweèti (Snare Lake), and Whati.

The 25 eligible communities in Nunavut are Arctic Bay, Arviat, Baker Lake, Cambridge Bay, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Gjoa Haven, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Kugluktuk, Naujaat, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Resolute, Sanikiluaq, Taloyoak, and Whale Cove.

The 1 eligible community in Alberta is Fort Chipewyan.

The 3 eligible communities in Saskatchewan are Fond‑du‑Lac, Uranium City, and Wollaston Lake.

The 16 eligible communities in Manitoba are Brochet, God’s Lake Narrows, God’s River, Granville Lake, Island Lake (Garden Hill), Lac Brochet, Little Grand Rapids, Negginan (Poplar River), Oxford House, Pauingassi, Red Sucker Lake, Shamattawa, St. Theresa Point, Tadoule Lake, Waasagomach, and York Landing.

The 27 eligible communities in Ontario are Angling Lake, Attawapiskat, Bearskin Lake, Big Trout Lake, Cat Lake, Deer Lake, Eabamet Lake (Fort Hope), Favourable Lake (Sandy Lake), Fort Albany, Fort Severn, Kasabonika, Kashechewan, Keewaywin, Kingfisher Lake, Lansdowne House, Muskrat Dam, North Spirit Lake, Ogoki, Peawanuck, Pikangikum, Poplar Hill, Sachigo Lake, Summer Beaver, Wawakapewin, Weagamow Lake, Webequie, and Wunnummin Lake.

The 22 eligible communities in Quebec are Akulivik, Aupaluk, Chevery, Harrington Harbour, Inukjuak, Ivujivik, Kangiqsualujjuaq, Kangiqsujuaq, Kangirsuk, Kuujjuaq, Kuujjuarapik, La Romaine (Gethsémani), La Tabatière, Mutton Bay, Port‑Menier, Puvirnituq, Quaqtaq, Saint Augustin/Pakuashipi, Salluit, Tasiujaq, Tête‑à‑la‑Baleine, and Umiujaq.

The 7 eligible communities in Newfoundland and Labrador are Black Tickle, Hopedale, Makkovik, Nain, Natuashish, Postville, and Rigolet.

Focus of the audit

12.12 This audit focused on whether selected federal departments and agencies protected Canada’s food system during the COVID‑19 pandemic by effectively designing, delivering, and managing programming to

- help reduce food insecurity in Canada through the Emergency Food Security Fund, the Surplus Food Rescue Program, and the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program

- support the resilience of food processors in the agriculture and agri-food and the fish and seafood sectors through the Emergency Processing Fund and the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund

12.13 This audit is important because Canadians and parliamentarians need assurance that these programs achieved their intended outcomes by reaching Canadians facing food insecurity and by supporting the resilience of the food processing sector. Moreover, the findings of this audit may help government departments and agencies better prepare for future crises.

12.14 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

12.15 The Auditor General of Canada’s 2021 reports also include an audit report on the Temporary Foreign Worker Program in the agriculture sector. That report includes an examination of both the Mandatory Isolation Support for Temporary Foreign Workers Program and the Emergency On‑Farm Support Fund. Together, these initiatives were intended to assist agricultural producers in covering costs associated with the mandatory quarantine of temporary foreign workers and in improving health and safety on farms.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

12.16 Overall, we found that the government had not developed a national emergency preparedness and response plan that considered a crisis affecting the entire food system and Canadians’ food security. This is despite the government having identified food as a critical infrastructure sector since 2009. Nevertheless, we found that the responsible departments and agencies we examined drew on existing programs and mechanisms to expedite the creation of the new emergency food programs. They also engaged broadly with various stakeholders across the food sector to inform the design of these programs.

12.17 We found that, although gender-based analysis plus and sustainable development were considered during the design of each program, the responsible departments and agencies could not always measure gender and diversity outcomes, and the programs’ contributions to sustainable development were not always clear.

12.18 We found that the responsible departments and agencies had many oversight controls in place for the delivery of the emergency food programs and monitored that the funding was spent as directed. However, we also found some inconsistencies in program design, which led to unfair treatment of applicants and recipients across regions.

12.19 We also found that each of the programs helped to mitigate some effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on elements of Canada’s food system. However, because of shortcomings in how the responsible departments and agencies gathered information, they could not show that they had achieved results against all of the outcomes intended to reduce food insecurity or support the resilience of food processors in the agriculture and agri-food and the fish and seafood sectors.

Designing the emergency food programming

The government had no national emergency preparedness and response plan for Canada’s food system

12.20 We found that, despite the government having identified food as a critical infrastructure sector, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada, as the lead federal department for the food sector, had not developed a national emergency preparedness and response plan that considered the entire food system and Canadians’ food security before the COVID‑19 pandemic began. Although the department had developed some emergency plans, it did not have an action plan to respond to a crisis that would affect the entire food system.

12.21 We also found that engagement with stakeholders helped the selected departments and agencies understand needs brought on by the pandemic across the food sector and develop the emergency programs that we examined.

12.22 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- No national emergency preparedness and response plan for the entire food system

- Broad engagement to inform program design

12.23 This finding matters because it is impossible to know when the next crisis affecting Canada’s food system will emerge or what form it will take. An effective response to a rapidly unfolding crisis depends on collaboration, coordination, and integration by all partners to facilitate coherent action. This in turn depends on these partners having clear and appropriate roles, responsibilities, authorities, and capacities. Emergency preparedness and response planning before a crisis could involve evaluating a wider variety of models of intervention, giving the government more flexibility to address issues such as worsening food insecurity.

12.24 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 12.29.

No national emergency preparedness and response plan for the entire food system

12.25 Before the pandemic, the government had recognized the importance of the food system and identified food as a critical infrastructure sector (see paragraphs 12.4 and 12.5). However, we found that the government’s emergency preparedness and response planning did not consider a crisis affecting the entire food system and the food security of Canadians.

12.26 In 2016, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada published the Emergency Management Framework for Agriculture in Canada, prepared by a federal, provincial, and territorial Emergency Management Framework Task Team. We found that this framework focused only on plant and animal health, and not on the food sector as a whole. Department officials told us that this framework was not activated in response to the pandemic and did not constitute a response plan.

12.27 In 2019, the department also put in place a Departmental Emergency Response Plan to give senior management and employees a clear description of the key roles, responsibilities, and governance structure that would be in place during an emergency. The plan was designed to support the department’s response to emergencies affecting the agriculture and agri-food sector. A key component of the plan was its incident management system, with elements of oversight, coordination, support, and operations. Department officials told us that this plan was also not used in response to the pandemic. This was because the plan had not been tested and because the department had determined that the plan was insufficient to tackle a government-wide response to a crisis affecting all of society.

12.28 We found that the lack of comprehensive emergency preparedness and response plans had negative effects on the department’s response to the crisis, especially in the early days of the pandemic. In August 2020, the department prepared an internal lessons learned report. This exercise identified several gaps and areas for improvement. Here are some examples:

- Unclear roles and responsibilities led to duplication of work, industry fatigue, and variation across jurisdictions about which services were essential.

- Before the pandemic, the department’s focus was mainly on food production and food processing. However, the pandemic caused disruptions across food supply chains, leading to intermittent shortages in grocery stores. The department determined that it needed to expand its engagement and support across the entire food supply system.

- Although the department undertook some planning and preparedness activities before the pandemic with provinces, territories, and stakeholders for emergencies affecting specific parts of the food sector, the focus was not on the entire food system. The internal report stated that enhanced joint planning and preparedness could have supported clearer roles and responsibilities and improved coordination for a quicker response. The report also noted that response plans by federal, provincial, and territorial governments, and by stakeholders, to address emergencies affecting the sector had been developed and implemented individually.

- Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada also stated in the report that the nature of federal legislative authorities and the department’s own authorities that might be needed in order to address sector effects and food security for Canadians had not been thought through before the pandemic. The report also stated that reviewing legislation and considering new authorities during the height of the crisis were not effective or efficient.

12.29 Recommendation. Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada should work with its federal, provincial, and territorial partners, as well as its stakeholders, to complete a national emergency preparedness and response plan for a crisis affecting Canada’s entire food system, taking into consideration the food security of Canadians.

Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Within the context of Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s mandate focused on the growth, sustainability, and competitiveness of the food supply chain, the department intends to engage with other relevant federal departments; federal, provincial, and territorial agriculture counterparts; and its stakeholders to develop an action plan to support the supply chain’s preparedness and response events in Canada. The intent of the action plan would be to outline a path forward for federal, provincial, and territorial governments and stakeholders. The action plan will consider the importance of food security and will recognize the need to support the effective functioning of the supply chain to provide food for Canadians.

This action plan will include a gap analysis and will put forward a feasible federal, provincial, and territorial and stakeholder approach by fall 2022.

Broad engagement to inform program design

12.30 We found that, despite the lack of a national emergency preparedness and response plan for the food system, most of the responsible departments and agencies did engage with various stakeholders in the design phase of the emergency initiatives. The aim of this engagement was to help the departments and agencies understand the risks, needs, and priorities of the food sector during the COVID‑19 crisis. The responsible departments and agencies also worked with one another to coordinate their initiatives.

12.31 Beginning in March 2020, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada organized daily conference calls with, at times, as many as 750 stakeholders across the food system to discuss the status of the crisis and emerging concerns. We found that the responsible departments and agencies used these and other engagement sessions to guide the design or development of the initiatives we examined. Here are some examples:

- In designing the Surplus Food Rescue Program, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada responded to stakeholder feedback about the increasing amount of surplus food in the supply chain and the high risk of spoilage. This feedback also informed the development of a list of eligible food items and a delivery method for the program.

- Feedback from processors informed the design of both the Emergency Processing Fund and the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund—for example, in determining what was eligible for funding, such as installation of protective barriers in processing plants.

- The criteria for selecting the food banks, food rescue organizations, and other assistance providers for the Emergency Food Security Fund were informed by a task force that included large not‑for‑profit organizations, food retailers, and government.

12.32 Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada did not conduct consultations with stakeholders to identify specific needs and priorities of northern and remote communities in response to the pandemic, or on how best to use the $25 million that the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program received.

Departments and agencies expedited the design and development of the emergency food programming we examined

12.33 We found that the responsible departments and agencies made use of mechanisms from existing programs to expedite the design and development of the emergency food programming we examined.

12.34 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

12.35 This finding matters because the government’s response to the COVID‑19 pandemic had to be both rapid and coordinated if it was to be effective. Use of existing mechanisms from similar, previously established programs, along with directing funding to proven third-party delivery organizations, could remove the need to build a program rapidly from scratch and could incorporate good practices from past successes.

12.36 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

Use of existing mechanisms to expedite program design

12.37 We found that to speed up the design, development, and approval of the emergency programming we examined, the responsible departments and agencies drew on a mix of existing mechanisms, rather than having to design entirely new program elements.

12.38 The 4 new programs—the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, the Emergency Processing Fund, the Emergency Food Security Fund, and the Surplus Food Rescue Program—made use of a mix of

- simplified processes for program and funding approvals, such as concurrence and off-cycle letters

- existing authorities, including amended terms and conditions of similar programs

- tools for the review of applications, such as templates and forms already in use by other programs

- experienced human resources, such as employees familiar with the economics of the regions they worked in

- procedures that they adapted to design elements, such as an advanced payment option for recipients

12.39 For the additional emergency funding it received, the existing Nutrition North Canada subsidy program continued to use mechanisms already in place. However, it did take advantage of the simplified processes for funding approval.

12.40 Across Canada, the Emergency Processing Fund also made use of external delivery organizations that had a track record and proven capacity to administer a high volume of applicants—as did the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund in British Columbia.

The contributions of the emergency programming to sustainable development and gender and diversity outcomes were not always measured

12.41 We found that when designing the emergency programming, the responsible departments and agencies we examined gave some consideration to their alignment with Canada’s sustainability and food-related goals and commitments, including those of the Food Policy for Canada. However, the programs’ contributions to those goals and commitments were not always clear. We also found that a gender-based analysis plus (GBA+)Definition 3 assessment was prepared for each initiative we examined. However, only in some cases did the responsible departments and agencies measure how the initiatives improved gender and diversity outcomes.

12.42 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

12.43 This finding matters because the federal government expects departments and agencies, when developing their programs and policies, to take into account the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. Government initiatives are also expected to respond to the needs of diverse groups of Canadians, including Indigenous peoples, while barriers to the full participation of diverse groups of women and men are identified and addressed or mitigated.

Source: United Nations

12.44 In September 2015, the 193 member states of the General Assembly of the United Nations, including Canada, unanimously adopted the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The 2030 Agenda contains 17 aspirational goals for social, environmental, and economic sustainable development worldwide. For example, the goal of zero hunger (Goal 2) aims to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture,” while the goal of gender equality (Goal 5) seeks to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

12.45 The 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy sets out the government’s environmental sustainability priorities, establishes goals and targets, and identifies actions to achieve them. A milestone completed under this strategy was the launch of the Food Policy for Canada to support the achievement of interdependent social, environmental, and economic outcomes, including improved access to safe and healthy food for all Canadians.

Source: United Nations

12.46 In 1995, the Government of Canada committed to using gender-based analysis to advance gender equality in Canada, as part of the ratification of the United Nations’ Beijing Platform for Action. Equality is also enshrined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Since 1995, the government has been committed to analyzing the gender-specific effects of policies, programs, and legislation on women and men throughout its departments and agencies. This commitment has since expanded to encompass many diverse groups, including Indigenous peoples.

12.47 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 12.51.

Unclear contributions to sustainable development

12.48 We found that in most cases, the responsible departments and agencies considered how their emergency programming would align with food-related policy commitments, their departmental sustainable development strategies, the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Exhibit 12.4). However, we also found that where they did make such linkages, the responsible departments and agencies did not always establish performance indicators that would allow them to show the contribution of these initiatives. Here are some examples:

- Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada included both the Surplus Food Rescue Program and the Emergency Food Security Fund in the department’s sustainable development strategy, indicating that they both linked to the Sustainable Development Goal of zero hunger (Goal 2) and the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy goal of sustainable food. The department also established performance indicators for the contribution of these 2 programs to this federal strategy goal, but not to Sustainable Development Goal 2.

- In the case of the Emergency Processing Fund, we found that the department considered alignment only to the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. The department did not develop any performance indicators to measure the program’s potential contributions to sustainability.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the regional development agencies considered the alignment of the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund with some sustainable development commitments. However, we found that they developed no performance indicators to measure the program’s contribution to those commitments.

Exhibit 12.4—The federal departments and agencies we examined did not always establish performance indicators to measure the contributions of the initiatives to sustainable development

Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund

| Program or initiative | 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy | Departmental sustainable development strategy | United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals | Food Policy for CanadaNote 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkages to sustainable development commitments | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Performance indicators to measure the initiative’s contribution to commitments | No | No | No | Not applicable |

Emergency Processing Fund

| Program or initiative | 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy | Departmental sustainable development strategy | United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals | Food Policy for CanadaNote 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkages to sustainable development commitments | Yes | No | No | No |

| Performance indicators to measure the initiative’s contribution to commitments | No | No | No | Not applicable |

Emergency Food Security Fund

| Program or initiative | 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy | Departmental sustainable development strategy | United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals | Food Policy for CanadaNote 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkages to sustainable development commitments | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Performance indicators to measure the initiative’s contribution to commitments | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable |

Surplus Food Rescue Program

| Program or initiative | 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy | Departmental sustainable development strategy | United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals | Food Policy for CanadaNote 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkages to sustainable development commitments | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Performance indicators to measure the initiative’s contribution to commitments | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable |

Nutrition North CanadaNote 2

| Program or initiative | 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy | Departmental sustainable development strategy | United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals | Food Policy for CanadaNote 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkages to sustainable development commitments | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Performance indicators to measure the initiative’s contribution to commitments | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable |

Gender and diversity outcomes not always measured

12.49 The federal government expected the responsible departments and agencies we examined to conduct GBA+ as part of the design of their initiatives. We found that the responsible departments and agencies completed these analyses. For example, the analysis for Nutrition North Canada showed that the subsidy program served communities that had larger proportions of low‑income individuals and Indigenous peoples, both of whom have been particularly vulnerable to the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

12.50 We also found that the responsible departments and agencies did not always set targets in support of GBA+ outcomes or measure the contributions of the programming to them:

- For the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, in support of improving gender and diversity outcomes, the regional development agencies established non‑repayable contributions (rather than repayable contributions) for not‑for‑profit groups and for Indigenous-controlled businesses. The regional development agencies also compiled data on the number of projects and funding in support of these and other groups, such as women-owned businesses. However, we found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the regional development agencies did not establish targets for the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund in support of GBA+ outcomes.

- For the Emergency Food Security Fund, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada required external delivery organizations to target 25% of a $25‑million round of the funding they received to Indigenous organizations or organizations serving Indigenous populations. The department’s Surplus Food Rescue Program set a target to make sure that 10% of the food under the program reaches the most vulnerable and remote communities, especially northern communities, many of which have predominantly Indigenous populations. We found that the department had met both of these targets.

- For the Emergency Processing Fund, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada included Indigenous groups as eligible applicants but had established no target for this support.

- Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada measured Indigenous inclusion for its 3 emergency programs (the Emergency Processing Fund, the Emergency Food Security Fund, and the Surplus Food Rescue Program). However, we found that the department did not request or gather any other data from recipients on progress toward gender and diversity outcomes.

12.51 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada should ensure that their future food-related initiatives measure and report on their contributions toward sustainable development commitments and to gender and diversity in order to improve assessment and outcomes.

Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada will ensure that future food-related initiatives include performance indicators, a gender-based analysis plus data collection plan, and reporting mechanisms to assess whether the initiatives contribute to sustainable development commitments, as well as to gender and diversity outcomes.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will ensure that where future food-related initiatives are developed under its purview, including any new food-related initiatives developed under the department’s Blue Economy Strategy, relevant targets and indicators are developed to inform Canadians of the initiatives’ contributions to sustainability and gender-based analysis plus outcomes, as required and on the basis of applicable reporting guidance.

Some inconsistencies in program design led to unfairness for applicants and recipients

12.52 We found that some design elements of the initiatives we examined led to unfairness for applicants and recipients across regions.

12.53 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

12.54 This finding matters because fairness to applicants and recipients is essential to building positive relationships with them, which is important to future programming, whether or not in an emergency situation. Fairness across regions is also essential to engendering the public’s trust.

12.55 The Treasury Board’s directive under the Policy on Transfer Payments requires government departments and agencies to ensure that transfer payment programs are delivered fairly to all involved, including applicants and recipients. The directive also includes requirements for the design and management of transfer payment programs to ensure that they are accountable, transparent, and effective. Department managers are expected to assess several core design elements of a transfer payment program and document evidence of their consideration of, for example,

- the identification of eligible recipients

- the identification of the types of eligible expenditures

- conditions that determine the amount and timing of repayment for contributions

12.56 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 12.64.

Inconsistencies for applicants and recipients

12.57 We found that there were several inconsistencies in the design elements of the initiatives we examined. While we acknowledge that a national program can be administered differently in various parts of the country to meet local needs, these specific inconsistencies led to unfair treatment of applicants and recipients across regions.

12.58 We found an inconsistency between 2 programs supporting the food processing sector. Although the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund allowed disposable personal protective equipment as an eligible expense, the Emergency Processing Fund did not, despite concerns raised by the meat processing industry during the design phase of the programs.

12.59 In the case of the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, we found that fish and seafood processors in both the Atlantic provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador) and western provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba) could apply for both repayable and non‑repayable funding. Until October 2020, however, the program in the Quebec region allowed only 1 type of funding per applicant: They could apply to receive funding for projects that were either repayable or non‑repayable, but not both. Applicants in different regions were also subject to different percentages of reimbursement for eligible activities. Finally, the deadlines for applying for funding varied across regions by more than a year and a half.

12.60 We also found that application deadlines for the Emergency Processing Fund varied across the fund’s regions by up to two and a half months. So, some applicants had shorter times than others to apply for funding. Furthermore, recipients in Canada’s western region (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, the Northwest Territories, and Yukon) received advance payments, starting in July 2020. However, in the 3 other regions of Quebec, central Canada (Ontario, Manitoba, and Nunavut), and Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador), recipients were required to submit claims for reimbursement. In central Canada and in Atlantic Canada, first payments did not begin until 4 or 5 months later than in the western region.

12.61 In the case of the Emergency Food Security Fund, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada did not have an open call for proposals. Instead, the department invited 5 organizations to apply for the available funding. All 5 organizations that received this funding were members of a task force who helped advise the department on the design of the program, including the eligibility criteria. The task force included nearly 30 food charities, a few private sector organizations, and some federal departments.

12.62 We found that the department later approved a sixth organization, despite having assessed that it did not meet all of the criteria: It did not have a national or regional reach or have an established track record for delivery of this type of programming.

12.63 We also found correspondence between department officials noting that there was a risk that other similar organizations would consider the process unfair because these organizations did not have an opportunity to participate in the program. We undertook a number of audit activities to further investigate if we could detect any indications of wrong doing in the selection of the recipients; we did not find any.

12.64 Recommendation. Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada should ensure that its future programs are delivered fairly and transparently to all involved, including applicants and recipients.

Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada strives to ensure fairness and transparency in all its programs, including during the unprecedented COVID‑19 pandemic when providing urgent financial support to help vulnerable Canadians living with food insecurity and to help Canadian food producers to maintain production.

Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada will strive to deliver future emergency programming with greater consistency, fairness, and transparency for all potential applicants and recipients.

Delivering the emergency food programming

Many controls were in place for the oversight of program delivery

12.65 We found that the responsible departments and agencies applied oversight controls for the delivery of 3 of the 4 initiatives we examined: the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, the Emergency Processing Fund, and the Emergency Food Security Fund. This included tracking applications, verifying recipient eligibility, obtaining proper approvals, and monitoring that the funding was spent as directed. However, we found that some steps in the application assessment processes were not always followed or documented.

12.66 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Application assessment processes not always followed or documented

- Timely funding decisions

- Proper oversight of spending

12.67 This finding matters because fair and transparent application processes, along with financial and performance reporting, assure Canadians and Parliament that public funds are being used as promised. The delivery of programming in emergency situations may present special challenges because of the need for a rapid response, but the requirements for accountability and transparency remain.

12.68 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

Application assessment processes not always followed or documented

12.69 We found that in 3 of the 4 programs (the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, the Emergency Processing Fund, and the Emergency Food Security Fund), the responsible departments and agencies had oversight controls in place for the review and approval of applications. This included processes for the review of applications against the program eligibility criteria, risk analyses, due diligence checklists, assessment grids, and approvals with the proper delegation of authorities. We also found that program officials obtained from applicants supporting documentation, such as financial statements, project plans, and business ownership details.

12.70 However, we also found some steps in the application assessment processes that were not always followed or documented. For example, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada did not adhere to all of the steps of its Grants and Contributions Management and Internal Control Framework:

- The department could not demonstrate that it had assessed whether any of the 30 applications to the Surplus Food Rescue Program had met the eligibility criteria. The department also did not complete the required financial risk analysis for any of the applicants to assess their financial position and assign a risk rating to them. By failing to complete these 2 key oversight steps, there was a risk that organizations could have been approved to receive funding without being eligible.

- In the case of the Emergency Food Security Fund, although the department conducted risk assessments for all 6 recipient organizations, these assessments took place only after the contribution agreements had been signed. This contravened the department’s Recipient / Project Risk Management Framework, which indicates that contribution agreements should include risk mitigation strategies.

Timely funding decisions

12.71 We found that for the 3 programs that had standards for making a decision to fund an applicant, the responsible departments and agencies met those standards a high percentage of the time (Exhibit 12.5). However, as noted in the paragraph above, 2 key oversight steps in the application assessment process were not completed for the Surplus Food Rescue Program.

Exhibit 12.5—The responsible departments and agencies we examined largely met their standards for making funding decisions

| Program or initiativeNote 1 | Department or agency standard: Number of business days to assess, review, and approve or reject an application | Number of cases examined | Number of cases that met the standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund | 35 to 90 | 40 (sample) | 35 (88%) |

| Emergency Processing Fund | 50 | 61 (sample) | 56 (92%) |

| Surplus Food Rescue ProgramNote 2 | 30 | 30 (population) | 28 (93%) |

Proper oversight of spending

12.72 We found that for the 4 initiatives with recipients (the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, the Emergency Processing Fund, the Emergency Food Security Fund, and the Surplus Food Rescue Program), the responsible departments and agencies exercised the proper oversight of the emergency spending. They had documented their approval and tracking of payments to the recipients.

12.73 We also found that recipients under each program provided the required final financial reports, and that the responsible departments and agencies completed their review and reconciliation of recipients’ financial information.

Achieving and reporting on results

Data and performance measurement problems prevented reliable reporting on outcomes

12.74 We found that the responsible departments and agencies we examined had data and performance measurement problems and could not demonstrate whether they had achieved all of their expected outcomes.

12.75 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Unreliable performance measurement by the regional development agencies

- Weaknesses with results measurement in each of Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s 3 emergency food programs

- Lack of data on pre‑subsidy food prices from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

12.76 This finding matters because, although the COVID‑19 pandemic was unprecedented in recent history, a crisis of this scale could happen again. Knowing the effectiveness of Canada’s response, as well as which of its aspects worked or could be improved, is essential to emergency preparedness for the critical food sector.

12.77 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 12.80 and 12.87.

Unreliable performance measurement by the regional development agencies

12.78 We found that the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund was able to demonstrate some progress toward its outcome on equipping sector businesses. However, it will be difficult for Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the regional development agencies to know the program’s effect on the second outcome: the recovery of Canada’s seafood processing sector (Exhibit 12.6).

Exhibit 12.6—The Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund could not provide reliable data on some results

| Expected program outcomes | Program results | Our findings |

|---|---|---|

| Seafood processing sector businesses are equipped to respond to recovery challenges as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic. |

As of 31 August 2021, of the 235 contribution agreements, 152 were non‑repayable contributions totalling $18.1 million that supported businesses in adapting health and safety measures. The fund had also provided $39.8 million through 83 repayable contributions that helped businesses increase their storage capacity or supported them with market development. |

The regional development agencies were able to demonstrate some progress toward the program’s outcome on equipping sector businesses. |

| Canada’s seafood processing sector has recovered from the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic. | The regional development agencies estimated that as of 31 August 2021, the program had directly supported nearly 13,000 jobs. | This overall estimate for the number of jobs supported was unreliable. The regional development agencies used different methods for collecting data and calculating the number of jobs supported. There were also instances of double counting, which means that this overall estimate was overstated. |

| Canada’s seafood processing sector has recovered from the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic. | No results were reported during the audit period on the number of businesses remaining in operation, as this is expected to be reported in the coming years. | This outcome depends on many factors beyond what the program measures. Therefore, it is difficult for the department and the regional development agencies to know the program’s effect on the recovery of the sector. |

Weaknesses with results measurement in each of Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s 3 emergency food programs

12.79 We found that Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada had weaknesses in how it measured results for all 3 of its emergency programs (Exhibit 12.7). These weaknesses included reliance on self-assessments by recipient organizations, unclear reporting requirements, and incomplete reporting by recipients.

Exhibit 12.7—There were weaknesses with the measurement of results for Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s 3 emergency food programs

Emergency Processing Fund

| Expected program outcomes | Program results | Our findings |

|---|---|---|

| Program recipients are able to maintain food production in Canada during the COVID‑19 pandemic. |

The department required the recipients that it directly funded to report on the changes in the numbers of production units, revenues, employees, and scheduled production hours before and after they received funding. As of 19 May 2021, about 63% of recipients had responded, and most of them reported increases in production, revenue, number of employees, and scheduled production hours. |

The department allowed recipients to report their figures on production units and revenues in different ways, making interpretation of the information difficult. The department required no supporting documentation from recipients to allow it to verify the data. |

| The health and safety of workers and their families is safeguarded. | The department asked recipients to complete a self-assessment on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“significantly”) of how much the funding had contributed to this outcome. The vast majority of recipients responded that the funding had contributed considerably (score of 4) or significantly (score of 5) to their ability to adapt to the health and safety protocols. | The department did not provide any guidance to recipients as to what was required to meet a particular score, which could make their responses inconsistent and of limited value for purposes of data analysis. The department also required no supporting documentation from recipients to allow it to verify the results. |

| Program recipients develop tools and strategies to adapt to the COVID‑19 pandemic or to increase domestic food production and processing capacity. | The department collected information from recipients on the numbers of tools, processes, equipment, and strategies developed and acquired, and on how the recipients used them to adapt to the COVID‑19 pandemic or increase domestic production. | Because this indicator included many different and incomparable measurements, and because the department did not require quantitative information to be reported in the same way against the indicator, the department could not conclude on whether the outcome was achieved. |

Emergency Food Security Fund

| Expected program outcomes | Program results | Our findings |

|---|---|---|

| The recipient organizations have increased their capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food during the COVID‑19 pandemic in communities supported by the funding. | The department asked the 6 recipient organizations to complete a self-assessment on a scale of 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“significantly”) on how much their projects contributed to the outcomes. Most of the organizations reported significant (score of 5) or considerable (score of 4) contributions to all 3 outcomes. | The department did not provide any guidance to recipients as to what was required to meet a particular score, which could make their responses inconsistent and of limited value for purposes of data analysis. The department also required no supporting documentation from recipients to allow it to verify the results. |

|

The organizations’ projects have increased the availability of and access to healthy and nutritious food during the COVID‑19 pandemic to constituents in communities supported by the funding. The organizations’ projects have reduced food insecurity in recipient communities during the COVID‑19 pandemic. |

The department also collected quantitative data from the recipients on the volume and value of food distributed, and on the number of meals and clients served, before and after receipt of the funding. | The quantitative data collected from the recipients was also not directly linked to these self-assessments. |

Surplus Food Rescue Program

| Expected program outcomes | Program results | Our findings |

|---|---|---|

| Organizations provide surplus food during the COVID‑19 crisis. | The department reported that as of 26 August 2021, the program had rescued (that is, purchased, distributed to vulnerable populations, and diverted from waste) 7.2 million kilograms of food, along with 1 million dozen eggs, totalling $39.9 million in food costs. | The department gathered the data it needed to report on results for this outcome. |

| Availability of and access to food are increased during the COVID‑19 crisis. | The department required the recipients to report on the quantities of food that they had distributed before and during the project. As of August 2021, 7 of the 9 recipients had submitted their performance reports during the audit period, with each providing quantitative data showing the amount of food they had distributed. | Three of the 7 organizations that reported did not have the data to show an increase in the amount of food distributed. |

| Food insecurity is reduced in recipient communities. |

Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada asked the recipients to complete a self-assessment on a scale of 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“significantly”) on how much their projects had contributed to reducing food insecurity in the communities they served. Seven of the 9 recipients completed this assessment during the audit period, with most indicating a “moderate” (score of 3) contribution. The department also collected quantitative data from the recipients on the volume and value of food distributed, and on the percentage of northern communities served, before and after receipt of the funding. |

The department did not provide any guidance to recipients as to what was required to meet a particular score, which could make their responses inconsistent and of limited value for purposes of analysis. The department also required no supporting documentation from recipients to allow it to verify the results. The quantitative data collected from the recipients was not directly linked to these self-assessments. |

12.80 Recommendation. Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada should ensure that its future initiatives have performance measurements that allow it to obtain sufficient, consistent, and relevant data to assess the achievement of outcomes.

Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada’s response. Agreed. Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada had in place performance measures to assess the results of the initiatives covered in this report. The results measurement weaknesses indicated by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada will be reviewed so that the department can learn from these initiatives and develop improved performance measurement strategies for future departmental initiatives to better enable effective measurement of and reporting on the achievement of program outcomes.

Lack of data on pre‑subsidy food prices from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

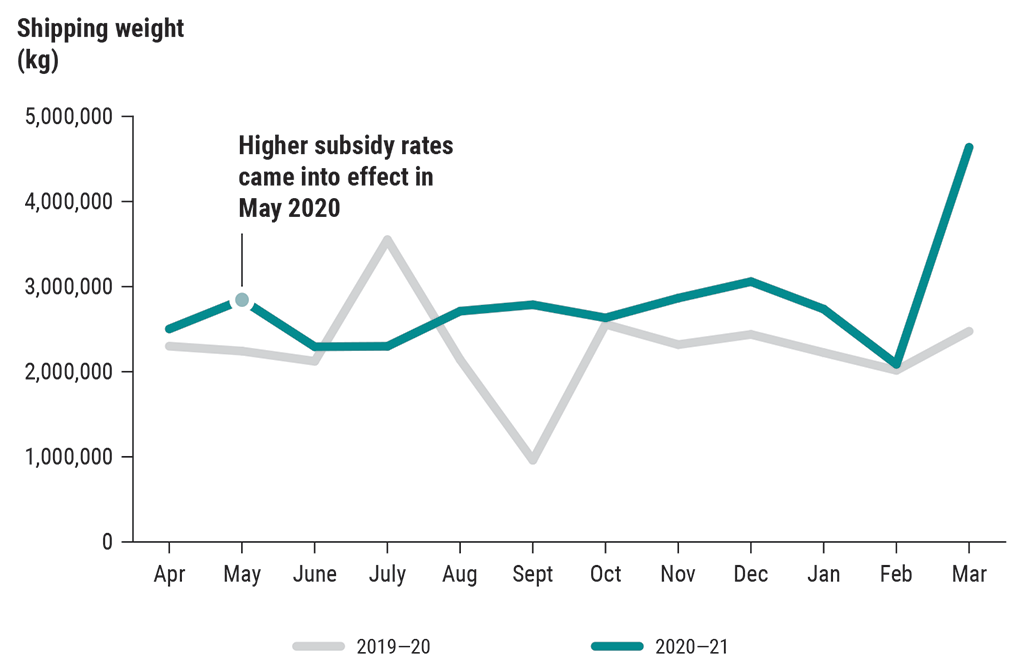

12.81 Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s Nutrition North Canada subsidy program has the dual outcomes of making food more accessible and more affordable in remote and isolated communities. To achieve these outcomes, the department applies subsidies to food items at low, medium, and high rates. The rates vary by eligible community. The additional COVID‑19 funding allocated to the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program applied to items subsidized only at medium and high rates. We found that the department had sufficient data to demonstrate progress on its outcome related to accessibility but not on its outcome related to affordability.

12.82 We found that the program had shipping data to demonstrate progress on the outcome of making food more accessible in remote and isolated communities, including during the pandemic (Exhibit 12.8).

Exhibit 12.8—Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada had Nutrition North Canada data to demonstrate increases in food accessibility in remote and isolated communities

| Expected program outcome | Program results | Our findings |

|---|---|---|

| To make food more accessible | The department had data to measure whether the program met its first outcome of increasing food accessibility. |

We used the program data to calculate the change in the amount of food items shipped to eligible communities. We found that from May 2020 to March 2021, when the higher subsidy rates applied, the amount of food shipped increased by approximately 24% compared with the same period a year before (Exhibit 12.9). This included items such as fresh fruit, vegetables, milk, and meat products, together amounting to about 68% of all food items shipped to eligible communities during the same period. |

Exhibit 12.9—The amount of eligible food items subsidized at medium and high rates that were shipped under the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program increased during the COVID‑19 pandemic

Source: Based on data from Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

Exhibit 12.9—text version

This line graph shows the monthly shipping weights (in kilograms) of eligible food items subsidized at medium and high rates that were shipped under the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program during the 2019–20 and 2020–21 fiscal years. In May 2020, during the COVID‑19 pandemic, higher subsidy rates came into effect, and from August 2020 to March 2021, the amount of food shipped increased compared with the same period a year before. During the 2020–21 fiscal year, the highest monthly amount shipped was 4,637,259 kilograms in March 2021. This amount was higher than the highest monthly amount shipped during the 2019–20 fiscal year, which was 3,551,159 kilograms in July 2019.

The monthly shipping weights in kilograms for the 2019–20 and 2020–21 fiscal years are as follows.

| Month | Amount in kilograms in 2019–20 | Amount in kilograms in 2020–21 |

|---|---|---|

| April | 2,300,129 | 2,502,475 |

| May | 2,242,305 | 2,845,217 |

| June | 2,122,784 | 2,293,633 |

| July | 3,551,159 | 2,298,642 |

| August | 2,141,591 | 2,711,354 |

| September | 960,238 | 2,786,988 |

| October | 2,557,329 | 2,632,528 |

| November | 2,318,210 | 2,865,200 |

| December | 2,438,273 | 3,058,749 |

| January | 2,224,426 | 2,735,812 |

| February | 2,016,322 | 2,086,834 |

| March | 2,475,477 | 4,637,259 |

12.83 For the program’s second outcome on making food more affordable, we found that the department did not collect pre‑subsidy pricing and, therefore, could not demonstrate the effect of the subsidy on food prices (Exhibit 12.10).

Exhibit 12.10—Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada did not collect pre‑subsidy pricing information under the Nutrition North Canada program

| Expected program outcome | Results reported | Our findings |

|---|---|---|

| To make food more affordable |

The department did not collect data on the prices of food items before the application of the subsidy. Rather, it gathered information on the prices only after retailers applied the subsidy. This limitation applied to the program as a whole, and not just to the $25 million in COVID‑19 funding that we examined. |

Without pre‑subsidy price data, the department could not calculate the effect of the subsidies on food affordability. |

12.84 To demonstrate the effect of subsidies on food prices, we obtained pre‑subsidy prices of a few food items in a store in Iqaluit, Nunavut. With this information, the effect of subsidies on food prices can be seen more clearly (Exhibit 12.11).

Exhibit 12.11—When data was available, the effect of the Nutrition North Canada subsidy on food affordability could be demonstrated, according to several examples

| Food item and quantity | Prices for June 2021 as shown on pricing labels in a store in Iqaluit, Nunavut | Statistics Canada data for June 2021 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‑subsidy price ($) | Post-subsidy price ($) | Post-subsidy price reduction (%) | Average price ($) across the 10 provincesNote 1 | |

| Bacon (375 grams) | $8.40 | $7.99 | -4.9% | $6.53Note 2 |

| Bananas (1 kilogram) | $6.91 | $3.29 | -52.4% | $1.77 |

| Butter (454 grams) | $8.26 | $6.69 | -19.0% | $5.14 |

| Eggs (1 dozen) | $7.05 | $4.29 | -39.1% | $4.12 |

| Milk (4 litres) | $21.69 | $5.59 | -74.2% | $5.93Note 3 |

| Carrots (2.27 kilograms) | $16.13 | $7.99 | -50.5% | $3.89Note 4 |

12.85 In the absence of the pre‑subsidy pricing data for the program, we used an indirect method to assess the effect of higher subsidy rates on food affordability, which the department applied during the pandemic. Where program data was available, we used it to examine the change in post-subsidy prices for 28 subsidized food items across eligible northern communities. We examined prices from May 2020 to March 2021 (when the higher subsidy rates were applied) against the same period a year before (when the lower subsidy rates were in effect before the pandemic).

12.86 The results showed considerable variation in price increases and decreases across food items and communities. For example, in 13 of the eligible communities, more than half of the subsidized food items we examined increased in cost when the higher subsidy rates applied, while in 9 other communities, more than half of the food items decreased in price.

12.87 Recommendation. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada should systematically collect pre‑subsidy prices for all eligible food items under the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program, to allow assessment of the extent to which the program is achieving its objective of making food more affordable in the eligible communities.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s response. Agreed. For the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada commits to working directly with registered retailers to collect pre-subsidy prices for all eligible items. The department will engage with retailers directly to obtain this new subset of data, working collaboratively on how best to make this transition.

The department will also review and amend the contribution agreements for all retailers to include an additional clause that pre‑subsidy prices are to be submitted to the program with their monthly subsidy claims.

The department’s projected timeline to implement this recommendation is 12 months.

Conclusion

12.88 We concluded that the emergency initiatives we audited had helped to mitigate some effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on elements of Canada’s food system. However, problems with data and performance measurement meant that the departments and agencies we audited did not know whether the initiatives had achieved all of their outcomes for reducing food insecurity or supporting the resilience of food processors in the agriculture and agri-food and the fish and seafood sectors.

12.89 We concluded that the responsible departments and agencies had many of the oversight controls in place for the delivery of the emergency food programs. However, Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada did not follow 2 key steps of the application assessment process for 1 of its programs. Also, there were some inconsistencies in program design across 3 of the initiatives that we examined, which led to unfairness for applicants and recipients across regions.

12.90 We also concluded that there was no national emergency preparedness and response plan for Canada’s food system and food security, despite the government having identified food as a critical infrastructure sector long before the COVID‑19 pandemic began. While Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada had 2 emergency plans in place, it acknowledged that they were insufficient to deal with a crisis of this magnitude. Nevertheless, the responsible departments and agencies drew on existing programs and mechanisms to expedite the creation of the new emergency food programs that we examined.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the protection of Canada’s food system during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the management of emergency programming to protect Canada’s food system complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether selected departments and agencies protected Canada’s food system during the COVID‑19 pandemic by effectively designing, delivering, and managing programs to reduce food insecurity in Canada and to support the resilience of food processors in the agriculture and agri-food and the fish and seafood sectors.

Scope and approach

This audit work focused on 5 initiatives that formed part of the government’s response to the COVID‑19 pandemic:

- the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund, implemented by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and delivered by the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions, and the former Western Economic Diversification Canada (which became 2 new agencies in August 2021: Pacific Economic Development Canada and Prairies Economic Development Canada)

- the Emergency Processing Fund, implemented by Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada

- the Emergency Food Security Fund, implemented by Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada

- the Surplus Food Rescue Program, implemented by Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada

- the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program, implemented by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

In our audit work on the design of the emergency programming, we examined whether

- the funding aligned with federal priorities for emergency management as well as Canada’s commitments to sustainable development and food-related policies and strategies

- there were documented processes for the identification of eligible recipients and initiatives

- there was engagement with stakeholders

- there was due consideration of gender and diversity

In our audit work on the delivery and management of the emergency programming, we examined whether applications by recipients were appropriately assessed against eligibility criteria, and whether controls were in place and followed for the use and reporting of the funding.

For the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund and the Emergency Processing Fund, we used representative sampling to examine applications. These samples were sufficient in size to project to the sampled population with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error (confidence interval) of +10%. For the Emergency Food Security Fund and the Surplus Food Rescue Program, we examined the review and approval of all of the applications for funding.

We did not examine files related to the funding disbursed by third-party organizations that helped deliver the Canadian Seafood Stabilization Fund and the Emergency Processing Fund. However, we examined the controls that these organizations had in place, and we conducted interviews with these organizations’ officials and with the program officials of the government departments and agencies.

As the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program did not have an application process, we examined the program’s data on subsidized food prices and shipments of food to eligible communities, to assess the effect of emergency funding on food affordability and availability. During our audit period, 116 communities were eligible under the program. However, 5 additional communities were made eligible under the program in August 2021.

In our audit work on whether the emergency programming achieved its intended outcomes and contributed to federal sustainable development commitments and food-related policies and strategies, we examined the extent to which the responsible departments and agencies were able to report on the achievement of their intended outcomes.

For the Emergency Food Security Fund, our examination covered the use of all of the first tranche of $100 million and most of the second tranche of $100 million. However, we did not examine the use of the third tranche, which was announced in August 2021, or Indigenous Services Canada’s use of the $30 million of the fund transferred to the department to bolster its Indigenous Community Support Fund. We also did not examine components of the Nutrition North Canada subsidy program that did not relate to the additional funding in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

We also did not audit several other initiatives announced by the federal government to respond to the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on Canada’s food system, partly because some were largely provincial in scope and because some focused on income support. We also did not audit liquidity support measures, such as loans for businesses, credit guarantees, or deferred tax payments as applied to the food sector.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether selected departments and agencies protected Canada’s food system during the COVID‑19 pandemic by effectively designing, delivering, and managing programs to reduce food insecurity in Canada and to support the resilience of food processors in the agriculture and agri-food and the fish and seafood sectors:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The department or agency ensures that the funding is aligned with the federal government’s emergency measures and Canada’s federal sustainable development commitments and food-related policies and strategies. |

|

|

The department or agency applies the required controls to the design and approval of the COVID‑19 funding. |

|

|

The department or agency appropriately assesses applications against the eligibility criteria. |

|

|

The department or agency delivers and manages the COVID‑19 spending in a manner that is transparent, accountable, timely, and sensitive to risks. |

|

|

The department or agency establishes or updates a performance measurement strategy in order to measure and report on progress associated with the COVID‑19 spending and its contribution to federal sustainable development commitments and food-related policies and strategies. |

|

|

The department or agency is achieving the intended outcomes with the COVID‑19 funding, is meeting the needs of stakeholders, and is contributing to federal sustainable development commitments and food-related policies and strategies. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 2 March 2020 to 4 June 2021. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 23 September 2021, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Kimberley Leach

Director: James Reinhart

Glen Barber

Hélène Charest

Allyson Fox

Michaël Hérot

Tristan Matthews

Victor Oligbo

List of Recommendations