2022—Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 4—Systemic Barriers—Correctional Service Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Systemic barriers to offenders in custody

- Indigenous and Black offenders were placed in higher security institutions

- Timely access to correctional programs continued to decline

- Indigenous offenders remained in custody longer than other offenders

- There was no plan or timeline in place to better reflect the diversity of the offender population in corrections staff

- Systemic barriers to offenders in custody

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 4.1—Changing offender population demographics

- 4.2—Offenders are eligible for release before the end of their sentence

- 4.3—Consideration of Indigenous social history

- 4.4—Overrepresentation of Indigenous and Black offenders initially classified as maximum security, April 2018 to December 2021

- 4.5—An increasingly lower percentage of offenders with sentences of 2 to 4 years completed correctional programs before their first parole eligibility

- 4.6—Correctional Service Canada designed specific correctional programs for men, women, and Indigenous offenders

- 4.7—Low percentages of offenders were prepared for release on parole when first eligible

- 4.8—Indigenous offenders were released on parole months later than other offenders

- 4.9—Indigenous representation gaps between correctional officers and offenders at institutions by region (as of April 2021)

Introduction

Background

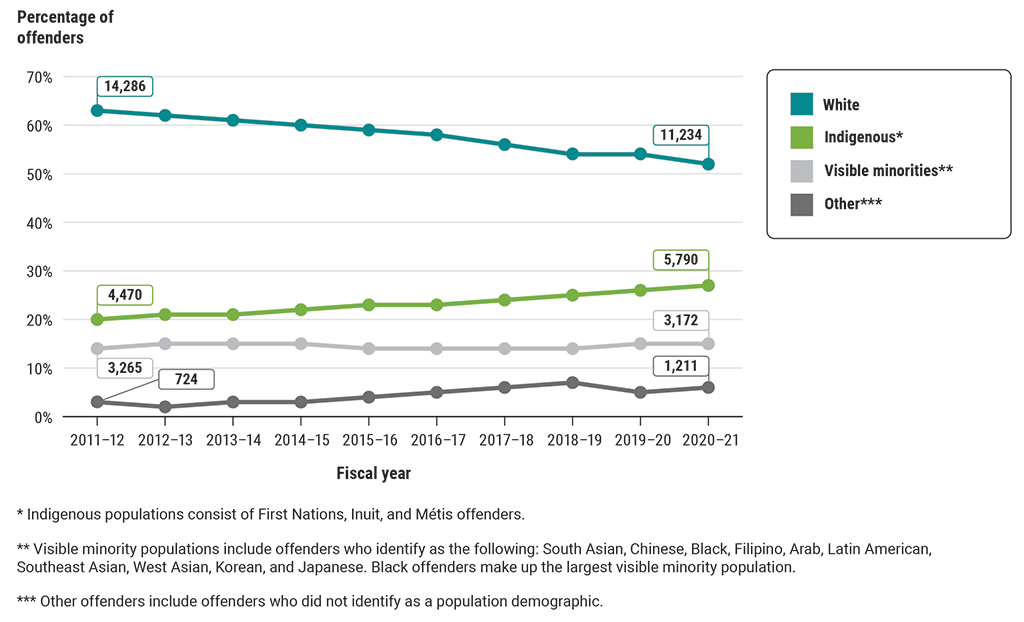

4.1 The demographics of the offender population have changed over the last 10 years (Exhibit 4.1). The overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the federal correctional system has grown. Indigenous peoples make up an estimated 4% of the Canadian adult population yet accounted for 27% of federal offenders in the 2020–21 fiscal year. In particular, Indigenous women make up 43% of women serving federal sentences in custody and are the fastest-growing population in the federal correctional system. Among visible minorities, Black people are overrepresented in federal custody, making up 3% of the general Canadian adult population but 8% of all federal offenders.

Exhibit 4.1—Changing offender population demographics

Note: The population groups shown are based on responses provided by offenders.

Source: Based on information from Correctional Service Canada

Exhibit 4.1—text version

This graph shows the changing offender population demographics over 10 fiscal years from 2011 to 2021. It also shows 4 groups of offender populations: white, Indigenous, visible minorities, and other. The population groups shown are based on responses provided by offenders.

Over the 10 years, the number of white offenders decreased but the Indigenous and other offender population groups increased. The visible minority population remained steady.

The number of white offenders steadily decreased from 14,286 (or 63% of all offenders) in 2011–12 to 11,234 (or 52% of all offenders) in 2020–21.

The number of Indigenous offenders steadily increased from 4,470 (or 20% of all offenders) in 2011–12 to 5,790 (or 27% of all offenders) in 2020–21. Indigenous populations consist of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis offenders.

The number of visible minority offenders remained steady, decreasing slightly from 3,265 in 2011–12 to 3,172 in 2020–21. The percentage of visible minority offenders also remained steady: It was 14% of all offenders in 2011–12 and 15% in 2020–21. Visible minority offenders include offenders who identify as the following: South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, Arab, Latin American, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Korean, and Japanese. Black offenders make up the largest visible minority population.

The number of offenders who did not identify as a population demographic is shown in a population group named “Other.” The number of these offenders steadily increased from 724 (or 3% of all offenders) in 2011–12 to 1,211 (or 6% of all offenders) in 2020–21.

4.2 In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada issued several calls to action regarding the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in Canada’s criminal justice system. The report called on the federal government to provide culturally relevant services to address both the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in federal penitentiaries and long‑standing differential outcomes for Indigenous offenders.

4.3 The Minister of Public Safety has recognized the urgent need to address systemic barriers for offenders in custody, and the Commissioner of Correctional Service Canada (CSC) has committed to doing so. In November 2020, CSC acknowledged systemic racism in the correctional system and launched an anti‑racism framework to identify and remove systemic barriers in the correctional system, with a focus on staff and offenders.

4.4 CSC employs more than 17,000 people and, as an employer, is responsible for supporting a diverse workforce. It also recognizes that a workforce that reflects the diversity of the offender population is more likely to possess the cultural competence, awareness, and sensitivity needed to deliver programs and services designed to support offenders’ successful reintegration into society.

4.5 In the 2020–21 fiscal year, CSC spent $496 million to deliver correctional programs to offenders in custody, which represents 18% of the total $2.8 billion spent on operations during the year. Correctional programs are designed to reduce an offender’s risk of reoffending after release. The programs address criminal behaviours involving violence, substance abuse, and sexual abuse. CSC also delivers programs meant to respond to the unique needs of women and Indigenous peoples. With an amendment to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act in 2019, CSC is also required to provide programs and services that respond to the unique needs of visible minorities.

4.6 CSC administers the sentences of offenders serving 2 years or more as determined by the courts. It provides correctional services that are intended to reduce offenders’ risk to public safety and prepare them for release on parole. As such, the point at which offenders receive these services has an impact on the length of time they remain in custody.

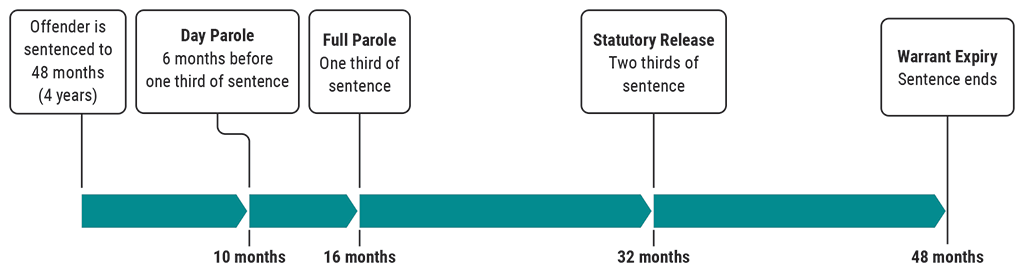

4.7 The average length of most sentences served in federal penitentiaries is less than 4 years (Exhibit 4.2), meaning that offenders are eligible to apply for parole within a year of admission. To prepare an offender for a parole hearing, CSC assesses each offender’s suitability for parole and provides a recommendation as to whether the offender should be granted or denied parole. Decisions about whether to grant parole (and under what conditions) are made by the independent Parole Board of Canada.

Exhibit 4.2—Offenders are eligible for release before the end of their sentence

Note: The timeline shows a sentence of 4 years as an example. During the period of the audit, 72% of the offenders admitted into federal custody had a sentence of between 2 and 4 years. Does not include offenders serving life sentences.

Exhibit 4.2—text version

This timeline shows when offenders, other than offenders serving life sentences, are eligible for different types of release and uses a sentence of 4 years as an example. During the period of the audit, 72% of the offenders admitted into federal custody had a sentence of between 2 and 4 years.

At the start of the timeline, the offender is sentenced to 48 months (or 4 years).

The offender is eligible for day parole at 6 months before one third of the sentence. This is at 10 months for an offender serving a 4‑year sentence.

The offender is eligible for full parole at one third of the sentence. This is at 16 months for an offender serving a 4‑year sentence.

The offender is eligible for statutory release at two thirds of the sentence. This is at 32 months for an offender serving a 4‑year sentence.

The offender’s warrant expires and the sentence ends at 48 months for an offender serving a 4‑year sentence.

4.8 The impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19) pandemicDefinition 1 on the public and on government operations since mid‑March 2020 has been extensive. Correctional institutions have not been spared by the pandemic. Several institutions experienced COVID‑19 outbreaks, requiring their operations to adhere to public health guidance on distancing and isolation measures. As a result, it had to adjust its traditional delivery of correctional programs and services to those in custody.

4.9 Our 2015, 2016, and 2017 audits of CSC found barriers to the timely preparation for release for the majority of offenders in custody. In particular, we found that more Indigenous offenders were placed at maximum-security institutions on admission than non‑Indigenous offenders, and that they did not have timely access to correctional programs, including those specially designed to meet their needs. Overall, those audits reported that the CSC rarely recommended offenders for release on parole, and when it did, it was generally months after they had become eligible.

4.10 Correctional Service Canada is responsible for providing correctional programs and services that address offenders’ criminal behaviour and that assist their reintegration into the community as law‑abiding citizens. Correctional programs and approaches are to respect offenders’ gender, ethnic, cultural, religious, and linguistic differences as well as their sexual orientation and gender identity and expression. These programs must also respond to the special needs of women, Indigenous peoples, visible minorities, people who need mental health care, and other groups. Furthermore, the CSC Commissioner, as deputy head of the agency, is responsible for fostering a diverse and inclusive workforce that meets or exceeds employment equity targets for management and staff.

Focus of the audit

4.11 This audit focused on whether Correctional Service Canada’s (CSC’s) programs respond to the diversity of the offender population to support their safe and successful return to the community. This included examining CSC’s policies and practices to promote workplace equity, diversity, and inclusion.

4.12 This audit is important because CSC is mandated to prepare offenders for safe release into the community and provide programs and interventions that are responsive to the unique needs of women, Indigenous peoples, and visible minorities.

4.13 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

4.14 Overall, we found that Correctional Service Canada failed to address and eliminate the systemic barriers that persistently disadvantaged certain groups of offenders in custody that we identified in previous audits. It also failed to develop a plan for its workforce to better reflect the diversity of the offender population. As a result, Indigenous and Black offenders faced greater barriers to a safe and gradual reintegration into society than other incarcerated groups.

4.15 Disparities are present from the moment offenders enter federal institutions. The process for assigning security classifications—including the use of the Custody Rating Scale and frequent overrides of the scale by corrections staff—results in disproportionately high numbers of Indigenous and Black offenders being placed in maximum-security institutions. While the majority of offenders were released on parole before the end of their sentences, Indigenous and Black offenders remained in custody longer and at higher levels of security before release.

4.16 Correctional programs are designed to prepare offenders for release on parole and support their successful reintegration into the community. We reported in 2015, 2016, and 2017 that timely access to these programs was a problem for offenders. We found that Correctional Service Canada had not adequately addressed this long‑standing situation. Access to programs declined even further during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Of men serving sentences of 2 to 4 years who were released from April to December 2021, 94% had not completed the correctional programs they needed before they were first eligible to apply for day parole. This is a barrier to serving the remainder of their sentences under supervision in the community.

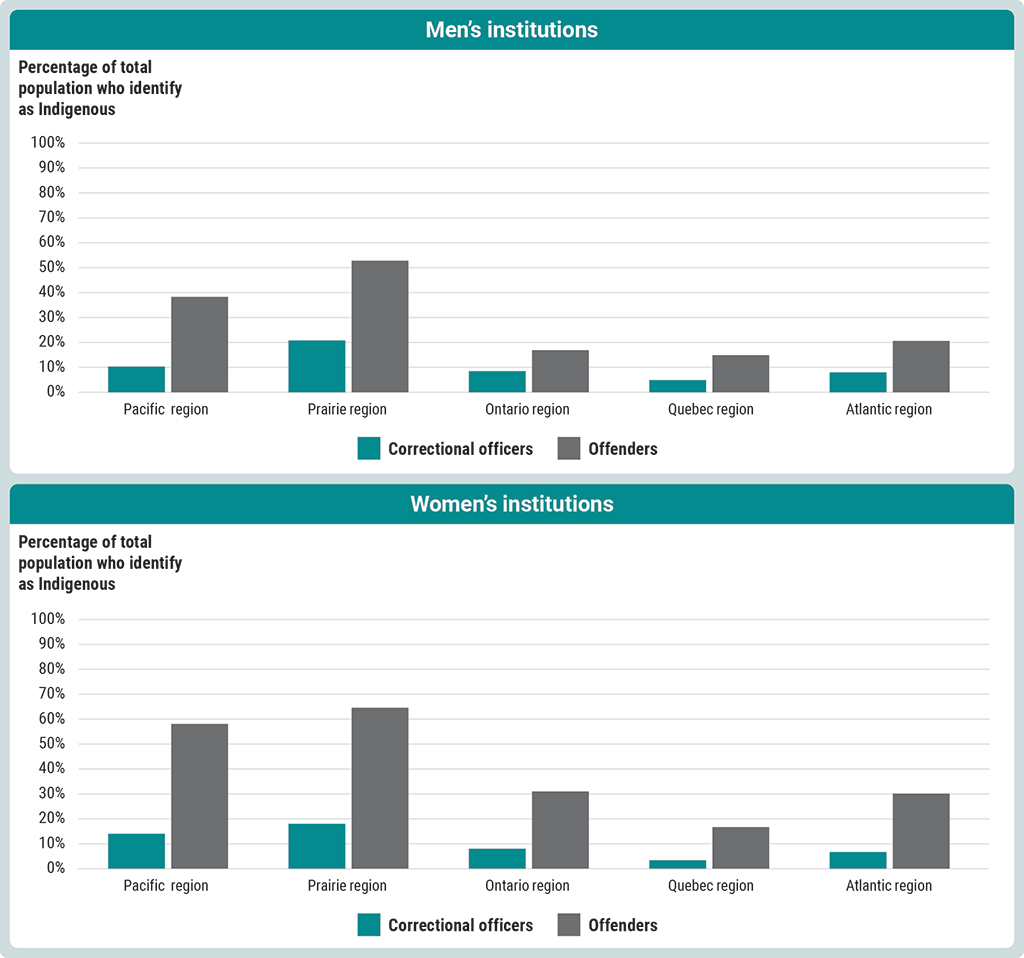

4.17 Correctional Service Canada’s efforts to support greater equity, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace fell short, leaving persistent barriers unresolved. Close to one quarter of management and staff had not completed mandatory diversity training a year after its deadline. We noted Indigenous representation gaps among correctional officers across institutions, Black representation gaps among program and parole officers at institutions with a high number of Black offenders, and gender representation gaps among correctional officers at women’s institutions.

Systemic barriers to offenders in custody

Indigenous and Black offenders were placed in higher security institutions

4.18 We found that Indigenous and Black offenders were placed at higher security levels on admission into custody at twice the average rate of other offenders. However, the reliability of Correctional Service Canada’s (CSC’s) security classification tool, the Custody Rating Scale, had not been validated since 2012, and its use had never been validated for Black offenders specifically. We also found that Indigenous offenders were more likely than non‑Indigenous offenders to have their initial security placement increased to a higher level through overrides of the Custody Rating Scale’s results. As well, we found fewer overrides down to minimum security for Indigenous offenders than for non‑Indigenous offenders.

4.19 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

4.20 This finding matters because offenders’ initial security placements affect their potentials for parole and the lengths of the sentences that they serve in custody. Offenders initially placed at minimum security are more likely to be granted parole by the time they are first eligible for release than those at higher levels. Identifying the tools, practices, and policies that result in a disadvantage for certain groups is critical in order to remove barriers in the correctional system.

4.21 Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, every offender is assigned a security classification of maximum, medium, or minimum when admitted to custody. Security classifications are based on an assessment of the level of supervision required and on the offender’s escape risk and risk to public safety in the event of escape. The assessments consider the seriousness of the offence, the offender’s social and criminal history, and potential for violent behaviour.

4.22 In June 2019, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act was amended to prohibit the consideration of the systemic and background factors affecting Indigenous offenders when assessing their security risk unless those factors could decrease the level of risk. In response, CSC has developed guidance and training to assist corrections staff with the consideration of Indigenous social history (Exhibit 4.3).

Exhibit 4.3—Consideration of Indigenous social history

The Corrections and Conditional Release Act requires Correctional Service Canada to consider systemic and background factors in decisions that affect Indigenous offenders, such as their security classification and institutional placement.

An Indigenous social history encompasses both the offender’s unique circumstances and the historical injustices connected with the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the criminal justice system—such as intergenerational trauma, dispossession, and loss of cultural and spiritual identity. Considering these factors, Correctional Service Canada may offer the offender a culturally appropriate or restorative justice solution, such as working with an Elder or being placed at a healing lodge.

Considering Indigenous social history is important because it gives those with decision-making powers greater insight into the factors that have contributed to an offender’s circumstances and can help Correctional Service Canada to address systemic barriers.

Correctional Service Canada’s Indigenous Social History tool includes a 4‑step process to guide officers in case management practices, such as during security assessments. However, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act does not permit Correctional Service Canada to consider Indigenous social history unless it will have a neutral or favourable impact on the offender’s risk level. In other words, the history and tool cannot be used to assign an offender to a higher level of security.

Four‑step process of the Indigenous Social History tool

1—Examine

Examine the direct and indirect systemic factors and familial history that may have affected the individual.

2—Analyze

When presenting recommendations and making decisions, analyze how the systemic and background factors have affected the individual’s actions or behaviours.

3—Options

Identify and consider what culturally appropriate and/or restorative options could contribute to reducing, addressing, and managing overall risk.

4—Document

Document the rationale used in recommendations and decisions, including culturally appropriate and/or restorative options considered in the process.

Source: Indigenous Social History tool, Correctional Service Canada, 2021

4.23 In 2019, the National Inquiry Into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls issued several recommendations pertaining to Indigenous women offenders in custody. In particular, it called on CSC to “evaluate, update and develop security classification scales and tools that are sensitive to the nuances of Indigenous backgrounds and realities.” It also called for a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections to be established to ensure accountability regarding Indigenous issues. In June 2021, the federal government released an action plan in response to the inquiry, and CSC committed to addressing the disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous people and to enhancing correctional outcomes for Indigenous women.

4.24 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.33.

Custody Rating Scale not recently validated

4.25 The Custody Rating Scale is an actuarial tool used in the process for deciding an offender’s initial security classification. It is used for all offenders admitted into federal custody. Among other factors, it gives greater weight to an offender’s age at sentencing, age at first federal admission, and number of prior convictions. While an offender’s age is a strong indicator of institutional misconduct, this can disadvantage Indigenous and Black offenders in particular because of their overrepresentation in the criminal justice system. On average, Indigenous and Black offenders are younger than other offenders admitted into custody.

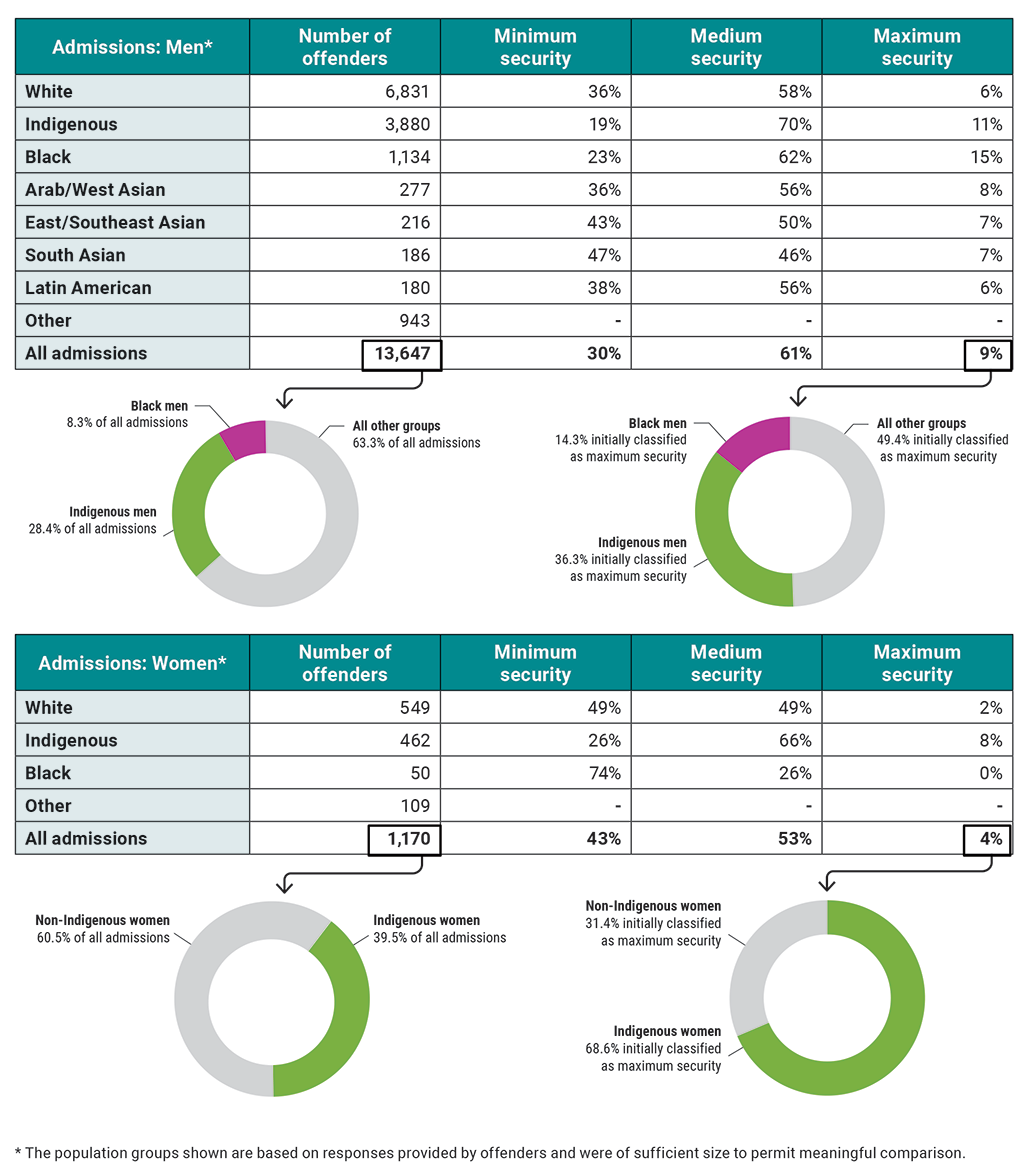

4.26 We found that more Indigenous and Black offenders were placed at maximum- and medium-security levels on admission than average (Exhibit 4.4). In fact, Indigenous and Black men were placed at maximum-security institutions at twice the rate of other offenders and made up 51% of maximum-security placements. We also found that Indigenous women were placed at maximum security at more than 3 times the rate of non‑Indigenous women and made up almost 70% of maximum-security placements. Results were similar in each of the 4 fiscal years we examined for both men and women.

Exhibit 4.4—Overrepresentation of Indigenous and Black offenders initially classified as maximum security, April 2018 to December 2021

Note: Percentages in the tables above are rounded.

Source: Based on information from Correctional Service Canada

Exhibit 4.4—Text version

The tables and charts in this exhibit shows 3 main types of information for the period from April 2018 to December 2021: the number of admissions of men and women offenders by demographic, the percentage of all admissions of each demographic of men and women offenders, and the percentage of men and women offenders initially classified as maximum security by demographic.

Overall, Indigenous and Black men and Indigenous women made up a larger percentage of the offenders initially classified as maximum security compared with offenders in other population groups. In contrast, Indigenous and Black men and Indigenous women made up a smaller percentage of all admissions than other groups.

From April 2018 to December 2021, 13,647 men were admitted into a federal correctional facility. Of these, 30% were classified at a minimum-security level, 61% were classified at a medium-security level, and 9% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 6,831 white men offenders: 36% were classified at a minimum-security level, 58% were classified at a medium-security level, and 6% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 3,880 Indigenous men offenders: 19% were classified at a minimum-security level, 70% were classified at a medium-security level, and 11% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 1,134 Black men offenders: 23% were classified at a minimum-security level, 62% were classified at a medium-security level, and 15% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 277 Arab/West Asian men offenders: 36% were classified at a minimum-security level, 56% were classified at a medium-security level, and 8% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 216 East/Southeast Asian men offenders: 43% were classified at a minimum-security level, 50% were classified at a medium-security level, and 7% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 186 South Asian men offenders: 47% were classified at a minimum-security level, 46% were classified at a medium-security level, and 7% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 180 Latin American men offenders: 38% were classified at a minimum-security level, 56% were classified at a medium-security level, and 6% were classified at a maximum-security level.

In the population group named “Other,” there were 943 men offenders. Percentages for the minimum-, medium-, and maximum-security levels were not provided.

The percentage of all admissions of different population groups of men offenders was compared with the percentage who were initially classified as maximum security. Indigenous men made up 28.4% of all admissions but 36.3% of the offenders initially classified as maximum security. Black men made up 8.3% of all admissions but 14.3% of the offenders initially classified as maximum security. Together, Indigenous and Black men made up 36.7% of all admissions but 50.6% of the offenders initially classified as maximum security. In contrast, all other groups made up 63.3% of all admissions but 49.4% of the offenders initially classified as maximum security.

From April 2018 to December 2021, 1,170 women were admitted into a federal correctional facility. Of these, 43% were classified at a minimum-security level, 53% were classified at a medium-security level, and 4% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 549 white women offenders: 49% were classified at a minimum-security level, 49% were classified at a medium-security level, and 2% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 462 Indigenous women offenders: 26% were classified at a minimum-security level, 66% were classified at a medium-security level, and 8% were classified at a maximum-security level.

There were 50 Black women offenders: 74% were classified at a minimum-security level, 26% were classified at a medium-security level, and 0% were classified at a maximum-security level.

In the population group named “Other,” there were 109 women offenders. Percentages for the minimum-, medium-, and maximum-security levels were not provided.

The percentage of all admissions of different population groups of women offenders was compared with the percentage who were initially classified as maximum security. Indigenous women made up 39.5% of all admissions but 68.6% of the offenders initially classified as maximum security. In contrast, non-Indigenous women made up 60.5% of all admissions but 31.4% of the offenders initially classified as maximum security.

The population groups for both men and women are based on responses provided by offenders and were of sufficient size to permit meaningful comparison. Percentages in the tables are rounded.

4.27 We note that overrepresentation of Indigenous men and women at higher levels of security is a long‑standing issue. We made similar observations in our 2016 audit.

4.28 The Custody Rating Scale has also not been recently validated for use to ensure that the tool functions as intended. CSC’s most recent validation of the scale’s reliability dates to 2012. The scale was developed more than 30 years ago using a sample of men offenders. It has never been validated for use with Black offenders. We note that CSC examined the potential merits of a re‑weighted scale for women in 2014, without implementing it. CSC is currently developing an Indigenous-informed risk assessment process and associated tools, in partnership with universities and Indigenous peoples. It is also important to validate its use with visible minority populations, including Black offenders, to address the risk of overclassification to higher levels of security.

Use of overrides disadvantaged Indigenous offenders

4.29 For each offender admitted into custody, corrections staff are to assess the Custody Rating Scale’s result to determine an offender’s security level. We found that corrections staff had overridden the result recommended by the Custody Rating Scale for 30% of all security assessments, with almost half to a higher level of security.

4.30 We also found differences among offender populations in the use of overrides across security levels. For Indigenous women, most overrides placed them to a higher security level: Corrections staff overrode up 53% of minimum-security placements, compared with 27% for non‑Indigenous women. For Indigenous men, corrections staff overrode up 46% of minimum-security placements to higher levels, compared with 33% for non‑Indigenous offenders. Only 10% of medium-security placements were overridden down for Indigenous offenders, compared with 19% for non‑Indigenous offenders. In contrast, most overrides lowered the security recommendations for Black men and women.

4.31 We reviewed a targeted selection of 20 security classification decisions for Indigenous offenders that resulted in a higher-level security placement than recommended by the Custody Rating Scale. Notes on the offenders’ case files indicated that the override was based on the offender’s security risk. Regarding the offender’s social history, none of the files considered whether culturally appropriate and restorative options could serve to decrease the offender’s level of risk, as required by the policy.

4.32 We found that CSC did not monitor whether corrections staff had properly considered an Indigenous offender’s social history for security classification decisions—including for overrides of the Custody Rating Scale. We noted that each recommended override must be approved by a manager. At the end of our audit period, CSC updated its policy to require further oversight by senior managers of overrides in security-level placement decisions for Indigenous offenders.

4.33 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should improve the initial security classification process for offenders by

- undertaking a review, with external experts, of the Custody Rating Scale and its use in decision making—in particular for women, Indigenous, and Black offenders—and, on the basis of the results, taking action to improve the reliability of security classification decisions

- monitoring the level and reasons for overrides to the Custody Rating Scale results across institutions and security levels—in particular for Indigenous offenders—and ensuring the proper consideration of Indigenous social history for security classification decisions

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See the List of Recommendations at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Timely access to correctional programs continued to decline

4.34 We found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) continued to face challenges in delivering correctional programs to offenders—including culturally specific programs to Indigenous offenders—by their first parole eligibility date. Timely access was significantly affected by the pandemic.

4.35 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

4.36 This finding matters because offenders are unlikely to be granted parole before they have successfully completed their assigned correctional programs. Timely access is particularly important for offenders serving short sentences who may be eligible for parole within a year of admission. Of offenders serving short sentences, 75% were referred to a correctional program.

4.37 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 4.45 and 4.46.

Delayed access to correctional programs

4.38 We found that over our audit period, there was a steady decline in access to correctional programs for all offender populations, which worsened with the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic. The majority of offenders are serving short sentences (2 to 4 years), and timely access is important as most are eligible to apply for parole within a year. Of offenders serving sentences of 2 to 4 years who were released from April to December 2021, only 6% of men were able to complete their correctional programs before they were first eligible to apply for day parole (Exhibit 4.5). This figure is significantly worse than before the pandemic and from our previous audits. In the 2018–19 fiscal year, 19% of men released completed their correctional programs before being eligible for parole. For women, before the pandemic, the completion rate was 50%—the same as was reported in our past audit. However, from April to December 2021, only 29% of women released had completed their programs before their first parole eligibility date.

Exhibit 4.5—An increasingly lower percentage of offenders with sentences of 2 to 4 years completed correctional programs before their first parole eligibility

| Population | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | April to December 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women offenders | 50% | 40% | 25% | 29% |

| Men offenders | 19% | 14% | 11% | 6% |

Source: Based on information from Correctional Service Canada

4.39 Timely delivery of correctional programs is particularly important for offenders serving short sentences (2 to 4 years), as most are eligible to apply for parole within a year of admission. We found that since the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, programs started about 9 weeks later and took 3 weeks longer to complete because program sessions were delayed or cancelled. We found similar trends among men and women and for culturally specific correctional programs for Indigenous offenders. Officials told us that public health physical-distancing requirements severely limited the timely delivery of programs during the pandemic. At the time our audit, CSC was examining options to speed up access to correctional programs, including improved scheduling and shifting to virtual access.

Gaps in collection of visible minority information

4.40 CSC has developed correctional programs to meet the unique needs of women and Indigenous offenders (Exhibit 4.6), and it confirmed their effectiveness in a series of research reports. However, their effectiveness has not been specifically assessed for offenders from visible minority populations. A recent evaluation demonstrated the effectiveness of correctional programs provided in the community to diverse groups of offenders on conditional release. Without research on offenders in custody, it cannot know whether its current programs are responsive to the unique needs of visible minorities, as required by the Corrections and Conditional Release Act.

Exhibit 4.6—Correctional Service Canada designed specific correctional programs for men, women, and Indigenous offenders

Correctional Service Canada’s correctional programs aim to reduce the risk of reoffending and increase public safety. They teach accountability and skills for managing risk factors. These programs target risk factors directly linked to criminal behaviour in order to reduce reoffending. They target crime for gain, general violence, domestic/family violence, substance abuse, and sexual offending.

| Programming for men | Programming for women | Programming for Indigenous offenders |

|---|---|---|

|

Integrated Correctional Program Model (ICPM) The model involves identifying the criminal risk factors for each offender. It teaches offenders to reframe these factors as personal goals and work toward reintegration with them in mind. The model also teaches offenders skills to address multiple risk factors. These skills include problem solving, goal setting, communication, emotional regulation, self‑management, and the ability to identify, challenge, and replace thinking that supports risky and criminal behaviour. |

Holistic approach that recognizes women’s social realities Women’s programs address problematic behaviours linked to crime, such as violence, substance abuse, and sexual offending. Programs of varying intensities include engagement and self‑management, Women’s Modular Intervention, and a program specifically for women sex offenders. These programs are a part of a continuum of care that supports women from their admission to their release. |

Culturally specific programs These programs are offered in most institutions for men and all for women. They are delivered by trained Indigenous or culturally competent correctional program officers. They

The model for Indigenous and Inuit men builds on the ICPM. Programs include

|

Source: Based on information from Correctional Service Canada

4.41 We also found that, while CSC was legally required in 2019 to provide programs and services tailored to the unique needs of offenders identifying as visible minorities, it had not updated its method to collect this information on the offender population to match that used by Statistics Canada for the Canadian population.

4.42 To collect information on visible minorities in the Canadian population, Statistics Canada gives respondents 11 population group mark‑in options (such as Black, Japanese, and so on) and 1 write‑in space. CSC, in contrast, uses over 30 mark‑in options that overlap race, ethnicity, and geography with no write‑in space. Officials noted that offenders had difficulty choosing among the overlapping mark‑in options.

4.43 On admission, offenders are asked to self‑identify their racial and ethnic background. This information is to be recorded in the offenders’ files by corrections staff. We found increasing levels of missing data for ethnic or race categories for offenders admitted into custody over the past 3 years. For example, we found that levels of missing data for offenders’ ethnic identifications increased from 2% in April 2018 to 6% in April 2021. Officials explained that this was due to an improper recording process in one of its biggest regions.

4.44 We noted that CSC had not conducted a gender-based analysis plusDefinition 2 assessment of its correctional programs and services for diverse groups of the offender population.

4.45 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should examine options in the delivery of correctional programs and take action to improve timely access and completion by offenders. Building on its recent evaluations of correctional programs, it should specifically examine their effectiveness with visible minority populations in custody, in particular with Black offenders.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See the List of Recommendations at the end of this report for detailed responses.

4.46 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should improve its collection of diversity information for offenders, ensure that the information is complete, and align its collection methodology with that of Statistics Canada. It should use this information to monitor the impact of its correctional policies and practices on diverse groups of offenders and to recognize and remove barriers to their successful reintegration.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See the List of Recommendations at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Indigenous offenders remained in custody longer than other offenders

4.47 We found that, although the majority of offenders were released on parole before the end of their sentences, fewer Indigenous offenders were released when first eligible. In fact, more Indigenous offenders remained in custody until their statutory release and were released directly into the community from higher levels of security. As a result, Indigenous offenders had disadvantaged access to a gradual and structured return to the community under parole supervision before the end of their sentences.

4.48 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

4.49 This finding matters because access to conditional release, including parole supervision, has consistently been demonstrated to contribute to an offender’s successful reintegration into the community. The timely release of offenders on parole has a direct bearing on public safety: Correctional Service Canada’s (CSC’s) own research indicates that offenders released on parole have lower rates of reoffending before their sentences end than those on statutory release.

4.50 Day or full parole is a form of conditional release granted by the Parole Board of Canada that permits offenders to serve the remainder of their sentence in the community under the supervision of CSC with specific conditions. If not granted day or full parole, most offenders serving fixed‑term sentences become eligible for statutory release after serving two thirds of their sentences in custody.

4.51 Statutory release is another form of conditional release whereby offenders may serve the remaining one third of their sentence under supervision in the community. The Corrections and Conditional Release Act requires CSC to release offenders by their statutory release date unless it has reasonable grounds to believe they are likely to commit an offence causing serious harm. Offenders first released at their statutory release date from maximum- and medium-security levels do not receive the full benefit of a planned, gradual release into the community provided at minimum-security institutions or on parole supervision.

4.52 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.58.

Late preparation of offenders for parole

4.53 We found that few offenders were prepared for release when they were first eligible: only 16% of men and 31% of women offenders on average from April 2018 to December 2021 (Exhibit 4.7). Moreover, we found that over these 4 years, both men and women Indigenous offenders were persistently released when first eligible at lower rates.

Exhibit 4.7—Low percentages of offenders were prepared for release on parole when first eligible

| Releases on parole—MenNote * | Number of offenders | Percentage released at first eligibility | Months past first eligibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 4,441 | 16% | 6 |

| Indigenous | 1,394 | 11% | 8 |

| Black | 620 | 16% | 7 |

| Arab/West Asian | 191 | 20% | 5 |

| East/Southeast Asian | 186 | 22% | 6 |

| South Asian | 135 | 20% | 5 |

| Latin American | 98 | 16% | 6 |

| Other | 324 | - | - |

| All releases on parole | 7,389 | 16% | 6 |

| Releases on parole—WomenNote * | Number of offenders | Percentage released at first eligibility | Months past first eligibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 536 | 32% | 3 |

| Indigenous | 303 | 20% | 6 |

| Other | 149 | - | - |

| All releases on parole | 988 | 31% | 4 |

Note: Percentages in the tables above are rounded.

Source: Based on information from Correctional Service Canada

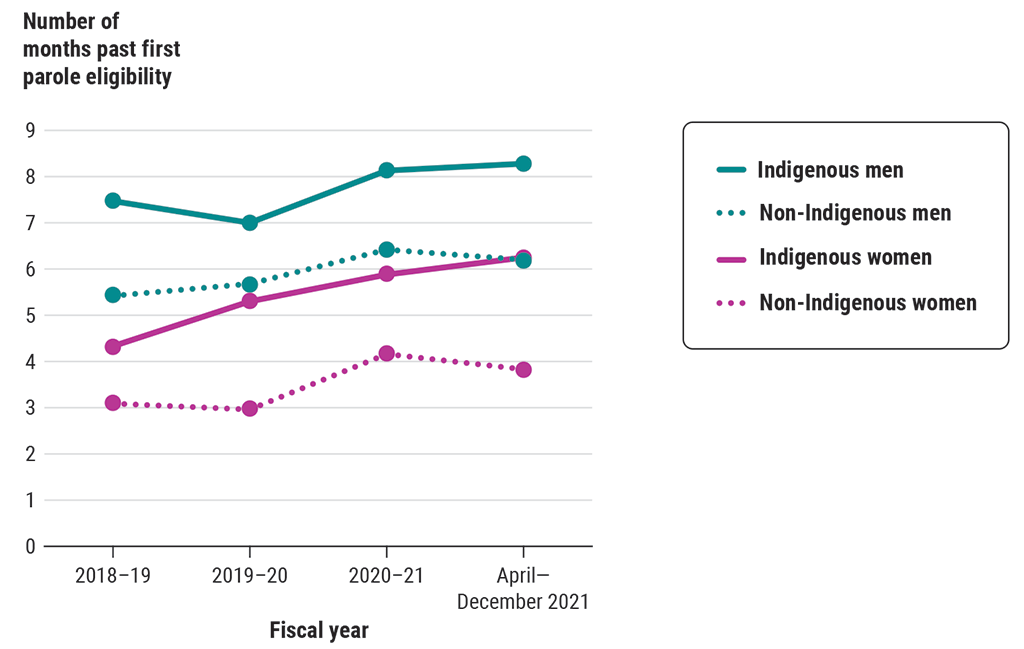

4.54 We also found that offenders were prepared for release on parole at later points in their sentence. Over our audit period, men offenders were released an average of 6 months after their first eligibility date. Women offenders were released an average of 4 months after their first eligibility date (Exhibit 4.7). Again, over the 4 years we examined, both men and women Indigenous offenders were persistently released 2 months later in their sentences than non‑Indigenous offenders (Exhibit 4.8). These results are similar to our past audits.

Exhibit 4.8—Indigenous offenders were released on parole months later than other offenders

Note: The population groups shown are based on responses provided by offenders.

Source: Based on information from Correctional Service Canada

Exhibit 4.8—text version

This chart shows the number of months past first parole eligibility that Indigenous and non‑Indigenous men and women offenders were released on parole. The period audited was from April 2018 to December 2021, and the population groups shown are based on responses provided by offenders.

Overall, over the almost 4 years audited, Indigenous men and women offenders were released on parole about 2 months later than non-Indigenous men and women offenders after they were first eligible for release on parole.

In 2018–19, Indigenous men were released 7.47 months after their first parole eligibility. Non‑Indigenous men were released 5.42 months after their first parole eligibility.

In 2019–20, Indigenous men were released 7 months after their first parole eligibility. Non-Indigenous men were released 5.68 months after their first parole eligibility.

In 2020–21, Indigenous men were released 8.13 months after their first parole eligibility. Non‑Indigenous men were released 6.42 months after their first parole eligibility.

From April to December 2021, Indigenous men were released 8.28 months after their first parole eligibility. Non‑Indigenous men were released 6.20 months after their first parole eligibility.

In 2018–19, Indigenous women were released 4.33 months after their first parole eligibility. Non‑Indigenous women were released 3.09 months after their first parole eligibility.

In 2019–20, Indigenous women were released 5.30 months after their first parole eligibility. Non‑Indigenous women were released 2.96 months after their first parole eligibility.

In 2020–21, Indigenous women were released 5.88 months after their first parole eligibility. Non‑Indigenous women were released 4.16 months after their first parole eligibility.

From April to December 2021, Indigenous women were released 6.25 months after their first parole eligibility. Non‑Indigenous women were released 3.83 months after their first parole eligibility.

Longer time in custody for Indigenous offenders

4.55 We found that with the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, offenders had been increasingly released at their statutory release dates. In particular, Indigenous men and women were released at their statutory release date at persistently higher rates than average: 33% and 52% higher, respectively. We found similar rates of release for Indigenous offenders in our previous audits. As a result, Indigenous offenders served longer portions of their sentences in custody than average, placing them at a disadvantaged access to earlier release on parole under supervision in the community.

4.56 Of the offenders released on statutory release, we found 15% of men and 21% of women were released directly into the community from maximum-security institutions. We also found an overrepresentation of Indigenous and Black men among offenders released directly from maximum-security institutions at their statutory release date, at 37% and 12% of releases, respectively. Indigenous women made up 66% of women offenders released directly from maximum security. Offenders first released at their statutory release date from maximum security do not receive the full benefit of a planned, gradual release into the community.

4.57 CSC’s policy requires offenders’ security levels to be reassessed following a significant event in their correctional plans, such as the completion of a correctional program. Among offenders released at their statutory release date, we found that almost all Indigenous offenders had their security level reassessed. About one quarter had their security level reduced, which can help support their successful transition into the community. However, the security reassessments were not timely: Only 34% of Indigenous offenders had their security level reassessed within the required 30 days of completing a correctional program. While CSC does not have a time requirement for non‑Indigenous offenders, three quarters had their security level reassessed, with one fifth resulting in a reduction in their security level.

4.58 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should identify and take action to address root causes contributing to delays in the preparation of offenders—particularly Indigenous offenders—for first release. Correctional Service Canada should also improve the timely completion of reassessments of offenders’ security levels, to facilitate their safe transitions into the community.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See the List of Recommendations at the end of this report for detailed responses.

There was no plan or timeline in place to better reflect the diversity of the offender population in corrections staff

4.59 We found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) had no set timeline to achieve its objective to better reflect the diversity of the offender population in its workforce. We also found that strategies and programs meant to support greater diversity and inclusion in the workplace fell short, leaving persistent barriers unresolved. CSC had not reviewed its employment systems to develop a plan to resolve identified barriers. Nationally, its workforce representation exceeded employment equity targets for the Indigenous peoples and visible minority groups but had employment equity gaps for women and people with disabilities.

4.60 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

4.61 This finding matters because under the Employment Equity Act, CSC is required to ensure that designated groups (women, Indigenous peoples, people with disabilities, and visible minorities) in its management and staff are reflective of the Canadian workforce availability. While CSC has exceeded the employment equity targets for the Indigenous peoples and visible minority groups, it has committed to go beyond these targets and aims to have its workforce be more reflective of the offender population. Identifying and removing barriers to equity-seeking groups is key to meeting this obligation, along with creating a work environment that supports diversity. Furthermore, CSC has recognized that having a more diverse workforce can improve correctional outcomes for offenders.

4.62 The Clerk of the Privy Council has recognized the need for federal organizations to go beyond the responsibilities outlined in the Employment Equity Act. In the 2021/2022 Deputy Minister Commitments on Diversity and Inclusion, each was directed to treat employment equity targets as a minimum goal. Furthermore, the mandate letter for the CSC Commissioner from the Minister of Public Safety noted that in the interest of effective rehabilitation, it is important that the full diversity of the offender population be reflected in its staff and management.

4.63 CSC is also obligated to create a workplace environment that supports greater diversity. In 2020, the Treasury Board issued its Directive on Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, which supports organizational policies and practices to promote an inclusive workplace. In 2021, the Clerk of the Privy Council put forth a Call to Action on Anti‑Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service, calling on leaders to set out a plan with actions to amplify marginalized voices and foster a more inclusive workplace. The Commissioner recognized the call to action as a priority and committed to taking action and engaging in initiatives that promote its objectives.

4.64 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 4.69 and 4.76.

Representation gaps at institutions

4.65 Beyond meeting its employment equity obligations, CSC has set goals to have a workforce that better reflects the diversity of the offender population. In 2021, it developed workforce representation objectives for Indigenous and visible minority offender populations by institution, adjusted by regional workforce availability. However, no implementation plan or timeline for meeting these objectives had been developed. We noted that the representation objective for visible minorities does not align with the overrepresentation of certain groups, in particular Black offenders.

4.66 As of April 2021, within its institutions, CSC had approximately 7,000 front‑line correctional officers and 2,700 front‑line parole and programs officers. We found representation gaps for Indigenous peoples between correctional officers and offenders in each region. These gaps were more pronounced at women’s institutions. At men’s institutions, these gaps were largest in the Prairie and Pacific regions, where the populations of Indigenous offenders are highest (Exhibit 4.9).

Exhibit 4.9—Indigenous representation gaps between correctional officers and offenders at institutions by region (as of April 2021)

Source: Based on information from Correctional Service Canada

Exhibit 4.9—text version

This chart compares the percentage of correctional staff with offenders who identified themselves as Indigenous in both men’s and women’s institutions in each region.

In all 5 regions, in both men’s and women’s institutions, the percentage of offenders exceeded by at least 2 times the percentage of correctional officers who identified themselves as Indigenous. The Prairie and Pacific regions had the greatest difference between offenders and correctional officers in both men’s and women’s institutions. But in women’s institutions, the differences between offenders and correctional officers were greater in all regions than in men’s institutions.

For men’s institutions, the regional percentages were as follows:

In the Pacific region, out of the total population, 10.3% of the correctional officers and 38.3% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Prairie region, out of the total population, 20.8% of the correctional officers and 52.8% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Ontario region, out of the total population, 8.5% of the correctional officers and 16.9% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Quebec region, out of the total population, 4.9% of the correctional officers and 14.9% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Atlantic region, out of the total population, 8% of the correctional officers and 20.6% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

For women’s institutions, the regional percentages were as follows:

In the Pacific region, out of the total population, 14% of the correctional officers and 58.1% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Prairie region, out of the total population, 5.9% of the correctional officers and 63.3% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Ontario region, out of the total population, 8.1% of the correctional officers and 31.4% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Quebec region, out of the total population, 3.4% of the correctional officers and 16.7% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

In the Atlantic region, out of the total population, 6.7% of the correctional officers and 30.1% of the offenders identified themselves as Indigenous.

4.67 Regionally, the Black offender population was highest at institutions for men in Ontario, at 18% of offenders in custody. At some institutions, this figure was much higher: At one maximum-security facility, 41% of offenders identified as Black, but only 2% of front‑line correctional officers and no front‑line parole or programs officers identified as Black. These gaps were not limited to the Ontario region. We found that at more than half of institutions where Black offenders made up more than 10% of the population in custody, CSC had no front‑line parole or programs officers who identified as Black.

4.68 Beyond meeting its employment equity targets for women, CSC aims to have women make up 75% of correctional officers at its 5 women’s institutions and 1 healing lodge. As of March 2021, the healing lodge and 3 of the 5 women’s institutions met this objective. Two institutions fell short of the target by approximately 10%. We also noted that the 75% target had not been formalized or supported by a plan to address resourcing challenges.

4.69 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should develop workforce representation objectives that align with the offender population in custody, with particular attention to overrepresented groups (such as Indigenous and Black offenders), and should formalize gender representation objectives at women’s institutions. In both cases, CSC should monitor progress according to an established timeline and consider which roles and functions (such as front‑line, institution-based officers) are priorities.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See the List of Recommendations at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Persistent employment equity gaps

4.70 Under commitments to increase workforce diversity, federal organizations are to treat employment equity targets as the floor and not the ceiling. CSC reported that it exceeded its employment equity targets (which correspond to Canadian workforce availability) for the Indigenous and visible minority groups at the national level in the 2020–21 fiscal year. However, it also reported that it did not meet the national targets for women and people with disabilities in the last 3 fiscal years, including for front‑line correctional officers.

4.71 CSC is required under the Employment Equity Act to review its employment systems, policies, and practices to identify and eliminate barriers to equity-seeking groups. In addition, the Commissioner has committed to closing employment equity gaps within its organization by 2025. CSC has identified the following issues affecting equity-seeking employee groups:

- unequal access to training and development opportunities

- lack of diversity knowledge and cultural competency to support Indigenous employees

- physical barriers, such as accessibility in buildings and institutions

- difficulties attracting women and Indigenous peoples to regional locations

- higher separation rates for equity-seeking groups, especially among women, than for non‑equity groups

CSC told us that it planned to finalize its review of its employment systems, policies, and practices in 2022.

4.72 In the 2016–17 fiscal year, CSC introduced mandatory training on diversity and cultural competency in the context of working with diverse offenders. In early 2021, this mandatory training was integrated into the new employee orientation programs so that all new staff would take the course. Existing staff were to complete the course by March 2020. As of March 2021, a year after the deadline, about 24% of its existing employees had still not completed the training. Most who had not done so were correctional officers. Additionally, about 16% of its executives had not completed the training as required.

4.73 We also noted that this course is only required to be taken once and that, despite changes made to course content in 2021, there is no refresher training. At the end of our audit period, the course was again undergoing review. This means that staff who have already taken this course will not have up‑to‑date knowledge. This training is important to increasing the cultural competency of staff to support a diverse and inclusive environment.

4.74 Consistent with the Minister of Public Safety’s 2019 mandate commitments, CSC is to provide training on unconscious bias. It reviewed the Canada School of Public Service’s online course offerings on this topic, found that they did not meet the needs of its operational context, and began developing its own training. At the end of our audit period, the unconscious bias course was in the pilot phase, with national implementation planned for the 2022–23 fiscal year.

4.75 CSC uses the results of the annual Public Service Employee Survey to gauge the success of its efforts to promote diversity and inclusion in its workforce. However, survey results indicate serious shortcomings. For example, from 2018 to 2020, less than two thirds of CSC employees agreed that CSC’s activities and practices supported a diverse workplace. Overall survey results were 21% lower for CSC than for the public service as a whole and comparatively lower among correctional officers and staff who identified as Indigenous, as a visible minority, or as a person with a disability.

4.76 Recommendation. To address employment equity representation gaps and increase the diversity and inclusivity of its workforce, Correctional Service Canada should

- finalize and implement its plan to address diversity and inclusion gaps, informed by an employment systems review and the results of the Public Service Employee Survey, to address systemic barriers to underrepresented groups

- ensure that all staff complete required diversity training and implement refresher training to ensure that they have the most up‑to‑date knowledge on these topics, in order to support a diverse and inclusive workforce

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See the List of Recommendations at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

4.77 We concluded that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) did not provide timely access to correctional programs to support offenders’ reintegration into communities, including programs specific to women, Indigenous peoples, and visible minorities. Systemic barriers limited access to programs and services that support successful reintegration, particularly for Indigenous and Black offenders.

4.78 The process for assigning security classifications—including the use of the Custody Rating Scale and frequent overrides of the scale by corrections staff—results in disproportionately high numbers of Indigenous and Black offenders being placed at higher levels of security. Very few offenders were able to complete their correctional programs before they were eligible to apply for parole, delaying their access to serve the remainders of their sentences under supervision in the community. While the majority of offenders were released on parole before the end of their sentences, higher numbers of Indigenous and Black offenders remained in custody longer and at higher levels of security until their release.

4.79 We also concluded that CSC had not succeeded in promoting diversity and inclusion, as measured by Public Service Employee Survey results. It has reported persistent gaps against its employment equity targets across both management and staff nationally. In addition, it has not established a plan to build a workforce that reflects the diversity of its offender populations, which has particular relevance for institutions with high numbers of Indigenous and Black offenders.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on systemic barriers faced by offenders in Correctional Service Canada institutions. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether Correctional Service Canada complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Correctional Service Canada delivers correctional interventions that respond to the diversity of the offender population and support offenders’ successful reintegration into society, supported by a workforce that reflects the diversity of the offender population, with policies and practices in place for equity, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace.

Scope and approach

We gathered audit information and evidence through interviews with Correctional Service Canada officials, document reviews, and analysis of offender and human resources data. Offender populations were based on offenders’ self‑identification collected by corrections officers.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether Correctional Service Canada delivers correctional interventions that respond to the diversity of the offender population and support offenders’ successful reintegration into society, supported by a workforce that reflects the diversity of the offender population, with policies and practices in place for equity, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Correctional Service Canada collects and analyzes information on its offender population to understand the changing diversity in its population. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada ensures that the tools and practices it employs across the diverse offender population are appropriate for their intended purpose. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada monitors the outcomes of key activities across diverse groups of offenders—such as the intake assessment, offenders’ correctional plans, interventions, and applications for release before the Parole Board of Canada—in order to identify groups that experience different outcomes. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada addresses the different outcomes experienced by identifiable groups at key points in their sentences to ensure that offenders do not experience significant differences. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada staff and management reflect the diversity of the offender population. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada has human resource strategies, policies, and programs that support equity, diversity, and inclusion and address the indicators in the Public Service Employee Survey related to a healthy workplace. |

|

|

Correctional Service Canada has implemented training for its staff so they are equipped to respond to the diverse offender population. |

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 April 2018 to 31 December 2021. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 20 May 2022, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Carol McCalla, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.33 Correctional Service Canada should improve the initial security classification process for offenders by

|

Agreed. Correctional Service Canada’s Research Branch will undertake a validation exercise of the Custody Rating Scale for Black men offenders and a revalidation for women and Indigenous offenders in collaboration with external experts. This work will commence this fiscal year and will be identified on the current year Research Plan. The results of this review in December 2023, as well as those from an Indigenous‑led initiative currently underway to develop an Indigenous-informed security classification process, will inform any action that may be required to improve the reliability of security classifications for these groups. Correctional Service Canada will start conducting a quarterly review of the reasons the initial Offender Security Classification decision differs from the Custody Rating Scale, in particular for Indigenous offenders, and ensure the proper consideration of Indigenous Social History for initial security classification decisions and placements. |

|

4.45 Correctional Service Canada should examine options in the delivery of correctional programs and take action to improve timely access and completion by offenders. Building on its recent evaluations of correctional programs, it should specifically examine their effectiveness with visible minority populations in custody, in particular with Black offenders. |

Agreed. Starting immediately, Correctional Service Canada will flag offenders serving short sentences with an identified program need in order to expedite their timely access into, and completion of, correctional programs. Correctional Service Canada has also undertaken a longer‑term innovative Virtual Correctional Program Delivery initiative to modernize the program scheduling, referral and assignment in order to improve the timely access and completion of correctional programs. This key component of the broader Virtual Correctional Program Delivery initiative will be implemented by the end of 2024. Correctional Service Canada will disaggregate the results of the most recent Evaluation of Correctional Reintegration Programs and will validate their effectiveness for the Black offender population by March, 2023. |

|

4.46 Correctional Service Canada should improve its collection of diversity information for offenders, ensure that the information is complete, and align its collection methodology with that of Statistics Canada. It should use this information to monitor the impact of its correctional policies and practices on diverse groups of offenders and to recognize and remove barriers to their successful reintegration. |

Agreed. To continue evolving its comprehensive data collection on the diversity of offenders, Correctional Service Canada will undertake a review of its approach to ensure its continued accuracy and alignment with Statistics Canada methodology. Correctional Service Canada will continue to monitor the diversity of the offender population to inform the development of its policies, programs and practices, and will continue to examine and report on results and outcomes of its diverse offender population. This ongoing work will be tied to the anticipated dissemination of the 2021 Census data relative to the Indigenous and ethnocultural composition of the population in Canada in Fall 2022. |

|

4.58 Correctional Service Canada should identify and take action to address root causes contributing to delays in the preparation of offenders—particularly Indigenous offenders—for first release. Correctional Service Canada should also improve the timely completion of reassessments of offenders’ security levels, to facilitate their safe transitions into the community. |

Agreed. Correctional Service Canada has already initiated an operational case review exercise to identify the root causes that contribute to the delays in the preparation and release of offenders by their first eligibility date, particularly Indigenous offenders and, based on the findings, necessary actions will be taken. CSC has also undertaken a case management initiative to enhance correctional planning, which will provide more robust tools to staff to ensure the timeliness of case preparation for release. Correctional Service Canada will implement a more robust tracking of cases by Summer 2022 to ensure the timely completion of reassessments of an offender’s security level and enhance national oversight to address non‑compliance. |

|

4.69 Correctional Service Canada should develop workforce representation objectives that align with the offender population in custody, with particular attention to overrepresented groups (such as Indigenous and Black offenders), and should formalize gender representation objectives at women’s institutions. In both cases, CSC should monitor progress according to an established timeline and consider which roles and functions (such as front‑line, institution-based officers) are priorities. |

Agreed. Correctional Service Canada has historically exceeded the workforce availability for Indigenous peoples and visible minorities. In 2021, Correctional Service Canada set representation objectives for Indigenous and visible minority employees that further exceed workforce availability and take into account the offender population. Correctional Service Canada will formalize its gender representation objectives for women’s institutions by March 2023. Correctional Service Canada will review its progress against established representation objectives and prioritize its staffing efforts at sites and for occupational groups where larger gaps between staff and the offender population exist. Correctional Service Canada will monitor its progress against these objectives and report on the results annually. |

|

4.76 To address employment equity representation gaps and increase the diversity and inclusivity of its workforce, Correctional Service Canada should

|

Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will complete its employment system review by September 2022. This review, and the results of the Public Service Employee Survey, will inform the new Comprehensive Plan for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. The plan will be finalized by December 2022 and provide an action plan to address issues affecting equity-seeking employee groups. Correctional Service Canada will monitor its progress against the Comprehensive Plan for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion and report on the results annually. Correctional Service Canada will complete the implementation of its Diversity Cultural Competency Training by March 2023 for existing staff. Correctional Service Canada will conduct an ongoing review of its Diversity Cultural Competency Training and all other diversity training that is provided in order to ensure staff have the most up-to-date knowledge on the topic of diversity and cultural competency. |