2022 Reports 5 to 8 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 6—Arctic Waters Surveillance

At a Glance

Overall, the federal government has not taken the required action to address long‑standing gaps affecting its surveillance of Canada’s Arctic waters. As a result, the federal organizations that are responsible for safety and security in the Arctic region do not have a full awareness of maritime activities in Arctic waters and are not ready to respond to increased surveillance requirements. These requirements are growing as a warming climate makes our Arctic waters increasingly accessible to vessels and as interest and competition for this region grows.

The long‑standing issues include incomplete surveillance, insufficient data about vessel traffic in Canada’s Arctic waters, poor means of sharing information on maritime traffic, and outdated equipment. The renewal of vessels, aircraft, satellites, and infrastructure that support monitoring maritime traffic and responding to safety and security incidents has fallen behind to the point where some will likely cease to operate before they can be replaced. For example, the Canadian Coast Guard and Transport Canada risk losing presence in Arctic waters as their aging icebreakers and patrol aircraft near the end of their service lives and are likely to be retired before a new fleet can be launched. Compounding this issue is the useful service life of satellites, which are also nearing their end and currently do not meet the needs of federal organizations. Delays in renewing this equipment coupled with the lack of a contingency plan could significantly compromise these organizations’ presence in Arctic waters. Furthermore, some of the government’s investments in support of Arctic surveillance, such as the Nanisivik Naval Facility, provide little value.

Action is needed to close gaps and put equipment renewal on a sustainable path to provide a full picture of what happens in the Arctic, which is essential to developing the actions needed to monitor maritime activities and respond to threats and incidents.

Why we did this audit

- While this opening of Arctic waters presents economic opportunities, it also puts at risk a delicate ecosystem, which Canada must safeguard. At the same time, increasing interest in the Arctic includes renewed interest in the region for strategic and military purposes, and Canada’s decisions about surveillance of Arctic waters today may have long‑term effects on our sovereignty.

- Because vessel traffic in Arctic waters is likely to continue to increase in the coming decades.

- Because the lack of awareness about vessels in the Arctic creates vulnerabilities that, if left unaddressed, could lead to incidents that would affect Canada’s security, safety, environment, and economy.

Our findings

- Federal organizations’ actions did not address long-standing gaps in the surveillance of Arctic waters.

- While the Marine Security Operations Centres helped federal organizations collaborate on building maritime domain awareness, weaknesses in the mechanisms that support information sharing, decision making, and accountability affected the centres’ efficiency.

- Fleets, equipment, and infrastructure used for monitoring maritime traffic need timely replacement and enhancement.

- Existing infrastructure improvement projects were behind schedule and that the Nanisivik Naval Facility will not effectively support the vessels that operate in the Arctic.

Key facts and figures

- The Canadian Arctic has more than 162,000 kilometres of coastline—75% of Canada’s total coastline. Over the past 50 years, average summer sea‑ice coverage in the Canadian Arctic has dropped by about 40% because of climate change.

- From 1990 to 2019, the number of voyages in Canadian Arctic waters more than tripled.

- Surveillance involves all levels of government, local and Indigenous communities, and trusted international partners.

Highlights of our recommendations

- National Defence, Transport Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Canadian Coast Guard, working together, should take concrete actions to address the long‑standing gaps in Arctic maritime domain awareness, particularly the following:

- the inability to track vessels continuously and to identify non‑emitting vessels

- the barriers that prevent efficiently sharing and integrating relevant information about vessel traffic in Arctic waters

- National Defence, Transport Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard, and Public Services and Procurement Canada should

- identify options and take action to acquire equipment in a timely manner

- develop and approve contingency plans to address the risk of having reduced surveillance capabilities in the event that key satellites, ships, or aircraft cease to operate before they are replaced

Please see the full report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

Exhibit highlights

Map of Canadian Arctic waters

Note: Not all northern communities are represented on the map.

Text version

This map of Canada shows the boundary of the Canadian Arctic waters—that is, which bodies of water in the Arctic are included in the scope of the audit. It also shows where some northern communities are situated.

The southernmost point of the boundary ends at the 60th parallel. The mainland coastal boundary includes the northernmost tip of Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador at the east and all of the coastline of Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, and Yukon. The boundary encompasses the Beaufort Sea, part of Hudson Bay, and all of the Canadian islands north of mainland Canada.

Starting from the farthest north, cities and towns on the shores of the Canadian Arctic Waters include the following (all are in Nunavut): Alert, Nanisivik, Cambridge Bay, Kugaaruk, and Iqaluit. Not all northern communities are represented on the map.

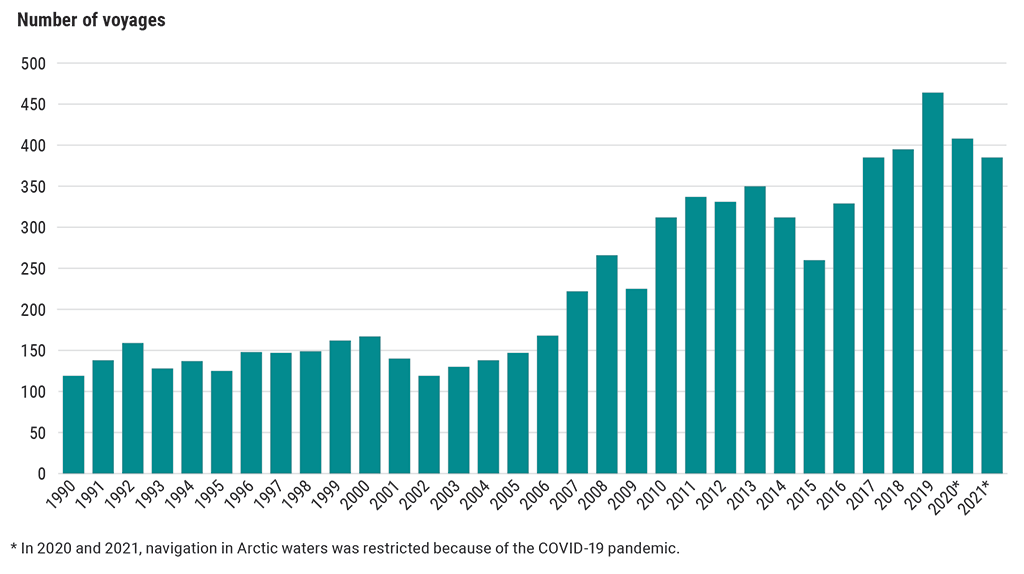

Maritime traffic increased significantly in the Canadian Arctic over the last decades

Source: The Canadian Coast Guard for data from 1990 to 2013, and Marine Security Operations Centres for data from 2014 to 2021

Text version

This chart shows the increase in maritime traffic over the last decades from 1990 to 2021.

In 1990, there were 119 voyages. Traffic remained within 50 voyages of that level until 2007, when the number of voyages increased to 222. Despite more significant dips in 2009 and 2015, the number of voyages rose steadily to 464 in 2019. It fell to 408 in 2020 and to 385 in 2021. In 2020 and 2021, navigation in Arctic waters was restricted because of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

The year‑by‑year data is presented below:

- In 1990, there were 119 voyages.

- In 1991, the number of voyages rose to 138.

- In 1992, the number of voyages rose to 159.

- In 1993, the number of voyages fell to 128 voyages.

- In 1994, the number of voyages rose to 137.

- In 1995, the number of voyages fell to 125.

- In 1996, the number of voyages rose to 148.

- In 1997, the number of voyages fell to 147 voyages.

- In 1998, the number of voyages rose to 149 voyages.

- In 1999, the number of voyages rose to 162.

- In 2000, the number of voyages rose to 167.

- In 2001, the number of voyages fell to 140.

- In 2002, the number of voyages fell to 119.

- In 2003, the number of voyages rose to 130.

- In 2004, the number of voyages rose to 138.

- In 2005, the number of voyages rose to 147.

- In 2006, the number of voyages rose to 168.

- In 2007, the number of voyages rose to 222.

- In 2008, the number of voyages rose to 266.

- In 2009, the number of voyages fell to 225.

- In 2010, the number of voyages rose to 312.

- In 2011, the number of voyages rose to 337.

- In 2012, the number of voyages fell to 331.

- In 2013, the number of voyages rose to 350.

- In 2014, the number of voyages fell to 312.

- In 2015, the number of voyages fell to 260.

- In 2016, the number of voyages rose to 329.

- In 2017, the number of voyages rose to 385.

- In 2018, the number of voyages rose to 395.

- In 2019, the number of voyages rose to 464.

- In 2020, the number of voyages fell to 408.

- In 2021, the number of voyages fell to 385.

Overview of sensor systems that monitor maritime traffic

Text version

This image shows an overview of the sensor systems that monitor maritime traffic.

Maritime traffic is monitored in a number of ways and by a number of systems. Local communities, ships, patrol aircraft, coastal automatic identification system towers, and satellites are some of the ways of monitoring traffic in Arctic waters.

The ships involved in patrolling Arctic waters are Royal Canadian Navy ships and Canadian Coast Guard icebreakers. Ships broadcast navigation information through various means, including the automatic identification system and the vessel monitoring system. Ships also communicate with each other.

Satellites, patrol aircraft, and coastal automatic identification system towers gather and relay information about ships to facilities on land, including with the Marine Security Operations Centre.

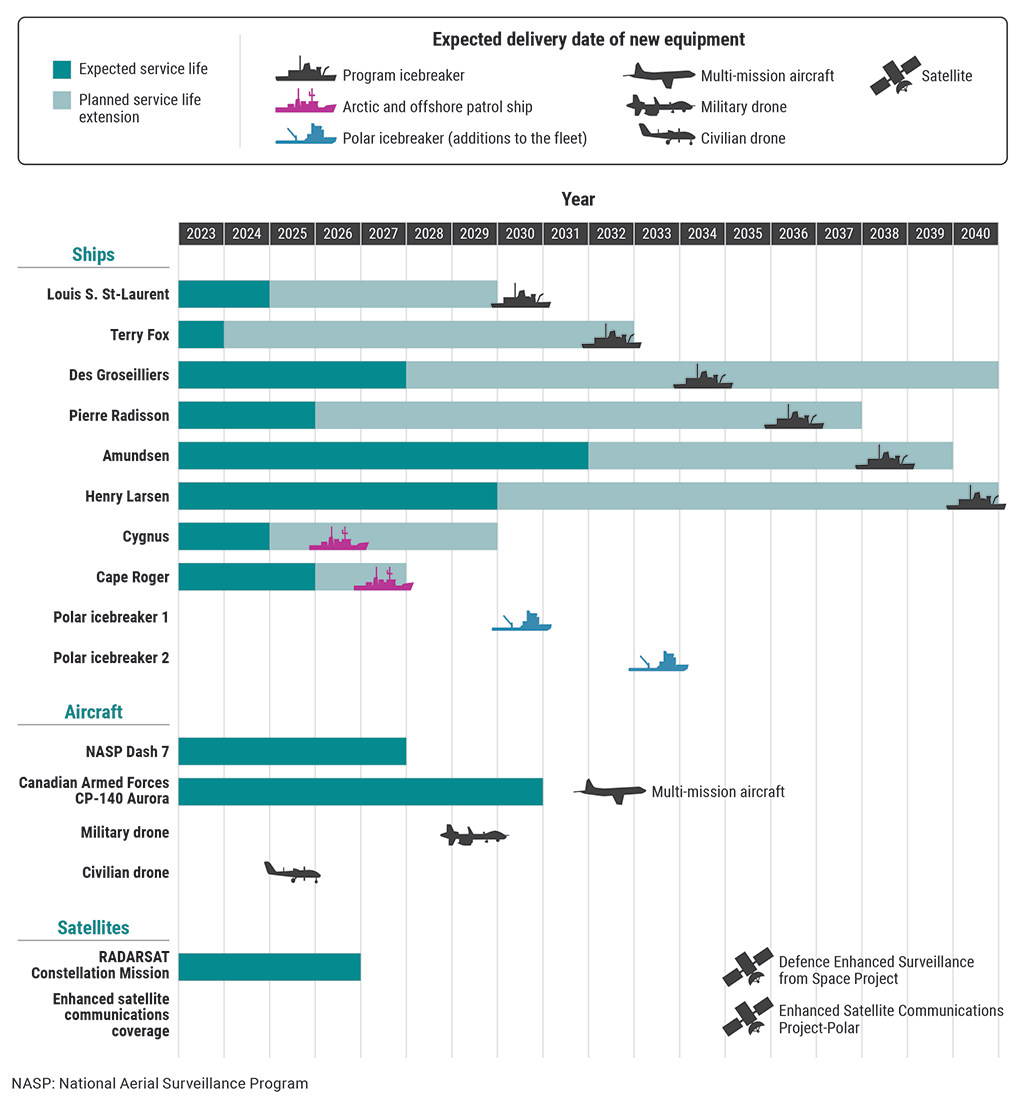

Existing equipment may reach the end of its service life before new equipment is ready, and equipment for new capabilities will not be ready for some time

Text version

This chart shows the expected service lives and planned service life extensions of existing equipment and the expected delivery dates of new equipment, which includes ships, aircraft, and satellites.

Ships: Ten ships are listed, 2 of which will be polar icebreakers that will be new additions to the fleet when the equipment has been delivered.

The Louis S. St‑Laurent is a program icebreaker. Its expected service life ends in 2024, its planned service life extension ends in 2029, and the expected delivery date of a new program icebreaker is in 2030.

The Terry Fox is a program icebreaker. Its expected service life ends in 2023, its planned service life extension ends in 2032, and the expected delivery date of a new program icebreaker is in 2032.

The Des Groseilliers is a program icebreaker. Its expected service life ends in 2027, its planned service life extension ends in 2040, and the expected delivery date of a new program icebreaker is in 2034.

The Pierre Radisson is a program icebreaker. Its expected service life ends in 2025, its planned service life extension ends in 2037, and the expected delivery date of a new program icebreaker is in 2036.

The Amundsen is a program icebreaker. Its expected service life ends in 2031, its planned service life extension ends in 2039, and the expected delivery date of a new program icebreaker is in 2038.

The Henry Larsen is a program icebreaker. Its expected service life ends in 2029, its planned service life extension ends in 2040, and the expected delivery date of a new program icebreaker is in 2040.

The Cygnus is an offshore patrol ship. Its expected service life ends in 2024 and its planned service life extension ends in 2029. It is expected to be replaced by an Arctic and offshore patrol ship, which is expected to be delivered in 2026.

The Cape Roger is an offshore patrol ship. Its expected service life ends in 2025 and its planned service life extension ends in 2027. It is expected to be replaced by an Arctic and offshore patrol ship, which is expected to be delivered in 2027.

Two new polar icebreakers will be added to the fleet (icebreakers not yet named) and have expected delivery dates of 2030 and 2033, respectively.

Aircraft: Four aircraft are listed, 2 of which will be new drones when the equipment has been delivered.

The National Aerial Surveillance Program Dash 7 is an aircraft. Its expected service life ends in 2027.

The Canadian Armed Forces CP‑140 Aurora is a type of aircraft. Its expected service life ends in 2030, and the expected delivery date of new multi-mission aircraft is in 2032.

Two new aircraft additions are a military drone and a civilian drone. The expected delivery date of a new military drone is in 2029, and the expected delivery date of a new civilian drone is in 2025.

Satellites: Two satellites are listed, 1 of which is an existing satellite. Two new satellites will be added when the equipment has been delivered.

The RADARSAT Constellation Mission is a satellite system. Its expected service life ends in 2026, and the expected delivery date of the new Defence Enhanced Surveillance from Space Project is in 2035.

For enhanced satellite communications coverage, the new Enhanced Satellite Communications Project-Polar has an expected delivery date of 2035.

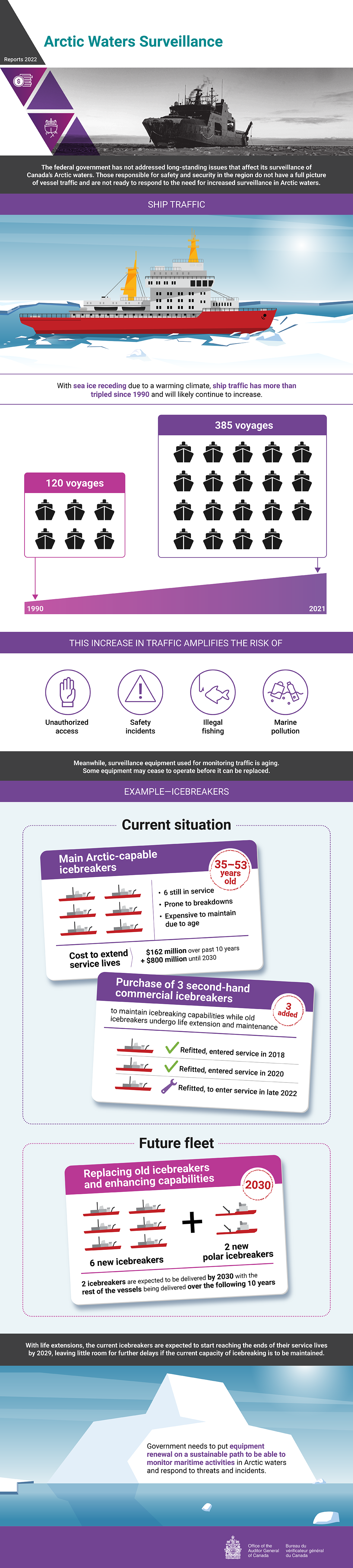

Infographic

Text version

This infographic presents findings from the 2022 audit report on the surveillance of Canada’s Arctic waters.

The federal government has not addressed long-standing issues that affect its surveillance of Canada’s Arctic waters. Those responsible for safety and security in the region do not have a full picture of vessel traffic and are not ready to respond to the need for increased surveillance in Arctic waters.

Ship traffic

With sea ice receding due to a warming climate, ship traffic has more than tripled since 1990 and will likely continue to increase.

In 1990, there were 120 voyages made in Canadian Arctic waters. By 2021, there were 385 voyages in Canadian Arctic waters.

This increase in traffic amplifies the risk of

- unauthorized access

- safety incidents

- illegal fishing

- marine pollution

Meanwhile, surveillance equipment used for monitoring traffic is aging. Some equipment may cease to operate before it can be replaced.

Example—Icebreakers

The example describes the current situation and the future fleet of icebreakers.

Current situation

Six main Arctic-capable icebreakers are still in service. They are between 35 and 53 years old. They are prone to breakdowns and expensive to maintain due to age.

Extending the service lives of these icebreakers cost $162 million over the past 10 years and is expected to cost $800 million more by 2030.

Three second-hand commercial icebreakers were purchased to maintain icebreaking capabilities while old icebreakers undergo life extension and maintenance. One was refitted and entered into service in 2018, another was refitted and entered into service in 2020, and a third was refitted and was to enter into service in late 2022.

Future fleet—Replacing old icebreakers and enhancing capabilities

Six new icebreakers and 2 new polar icebreakers are being acquired. Two icebreakers are expected to be delivered by 2030, with the rest of the vessels being delivered over the following 10 years.

With life extensions, the current icebreakers are expected to start reaching the ends of their service lives by 2029, leaving little room for further delays if the current capacity of icebreaking is to be maintained.

Government needs to put equipment renewal on a sustainable path to be able to monitor maritime activities in Arctic waters and respond to threats and incidents.

Related information

Entities

Tabling date

- 15 November 2022

Related audits

- 2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 2—National Shipbuilding Strategy - 2018 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 3—Canada’s Fighter Force—National Defence - 2016 Fall Reports of the Auditor General ofCanada

Report 7—Operating and Maintenance Support for Military Equipment—National Defence