2022 Reports 5 to 8 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 5—Chronic Homelessness

At a Glance

Overall, Infrastructure Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know whether their efforts improved housing outcomes for people experiencing homelessness or chronic homelessness and for other vulnerable groups.

As the lead for Reaching Home, a program within the National Housing Strategy, Infrastructure Canada spent about $1.36 billion between 2019 and 2021—about 40% of total funding committed to the program—on preventing and reducing homelessness. However, the department did not know whether chronic homelessness and homelessness had increased or decreased since 2019 as a result of this investment.

For its part, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, as the lead for the National Housing Strategy, spent about $4.5 billion and committed about $9 billion but did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives. This was because the corporation did not measure the changes in housing outcomes for priority vulnerable groups, including people experiencing homelessness. We also found that rental housing units approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund that the corporation considered affordable were often unaffordable for low-income households, many of which belong to vulnerable groups prioritized by the strategy.

Despite being the lead for the National Housing Strategy and overseeing the majority of its funding, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation took the position that it was not directly accountable for addressing chronic homelessness. Infrastructure Canada was also of the view that while it contributed to reducing chronic homelessness, it was not solely accountable for achieving the strategy’s target of reducing chronic homelessness. This meant that despite being a federally established target, there was minimal federal accountability for its achievement.

Moreover, the initiatives under the strategy were not integrated, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada were not working in a coordinated way. In our view, without better alignment of their efforts, Infrastructure Canada and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation are unlikely to achieve the federal National Housing Strategy target of reducing chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year.

Why we did this audit

- Experiencing homelessness, including chronic homelessness, affects an individual’s health, security, stability, and participation in society and the economy.

- Addressing housing needs for the most vulnerable Canadians, including people experiencing homelessness, promotes social and economic inclusion for individuals and families, reduces the number of households in core housing need, and contributes to preventing and reducing chronic homelessness.

Our findings

- Infrastructure Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada did not know whether their efforts to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness were leading to improved outcomes.

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives.

- There was minimal federal accountability for reaching the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year.

Key facts and figures

- Launched in 2017, the National Housing Strategy is a 10‑year, $78.5 billion federal strategy intended to improve housing outcomes and affordability for Canadians in need, including reducing chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year.

- Infrastructure Canada’s 2019 analysis indicated a disparity between homelessness—an 8% decrease—and chronic homelessness—an 11% increase. The absence of more recent results meant that the department did not know whether homelessness and chronic homelessness had increased or decreased since 2019.

- According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, affordability was the primary reason that about 76% of Canadian households were in core housing need and in 2016, the majority (66%) of households in core housing need were renting.

- More than 85% of Canadian households in core housing need had a before-tax income of less than $50,000. This meant that monthly rent would need to be less than $1,250 to be considered affordable.

Highlights of our recommendations

- Infrastructure Canada should; collect and analyze data in a timely manner, finalize the implementation of its online reporting platform, and use the information and data that it collects.

- The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation should assess the impact of its programs on vulnerable groups at all stages of its National Housing Strategy initiatives.

- The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada should align, coordinate, and integrate their efforts and engage with central agencies to clarify accountability.

Please see the full report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

The lack of a more recent estimate of chronic homelessness meant that the department did not report up‑to‑date information or make adjustments so that the Reaching Home program met its objectives and contributed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Specifically, Goal 11 is to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. A Canadian target related to this goal is to reduce chronic homelessness by at least 31% by March 2024. In our view, given the results as of 2019, it is unlikely this target will be met unless significant actions are taken.

Visit our Sustainable Development page to learn more about sustainable development and the Office of the Auditor General of CanadaOAG.

Exhibit highlights

The housing continuum

Source: Adapted from About Affordable Housing in Canada, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2018

Text version

The housing continuum has the following stages:

- Homelessness

- Emergency shelter

- Transitional housing

- Supportive housing

- Community housing

- Affordable housing

- Market housing

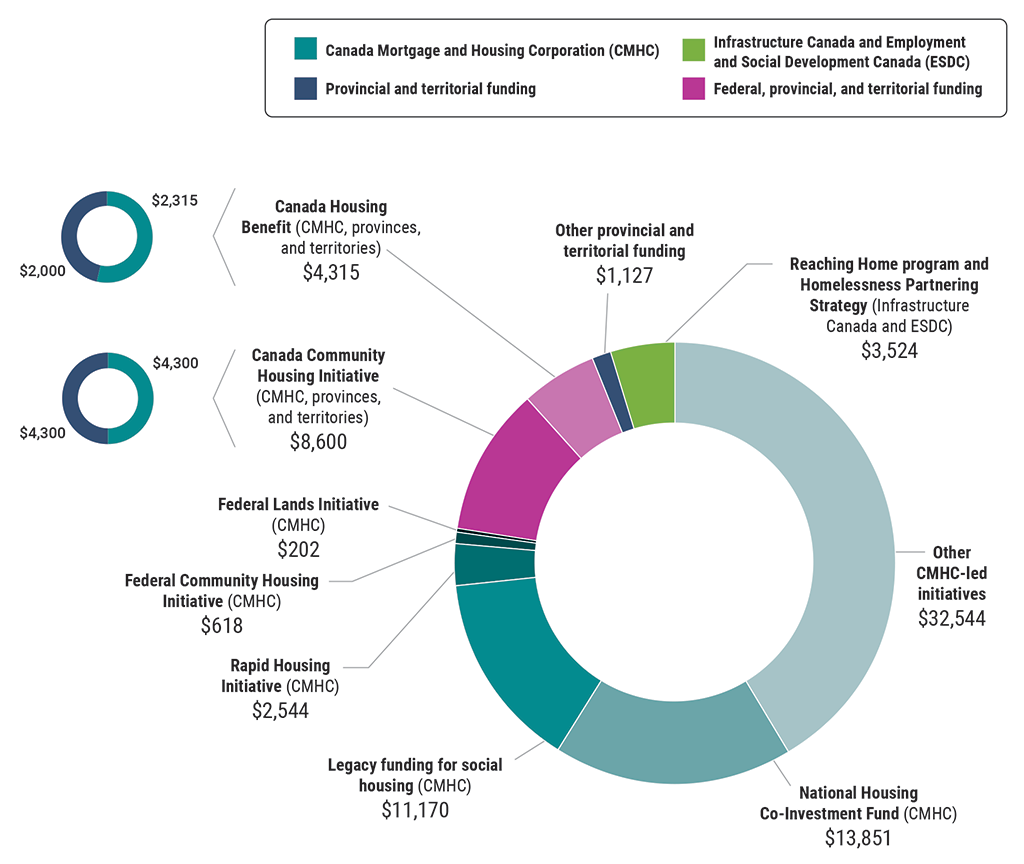

Breakdown of $78.5 billion in planned spending under the National Housing Strategy (amounts show are in millions of dollars)

Note: As part of the Budget 2022 announcement, an additional $580 million was announced for the Reaching Home program and an additional $2 billion was announced for CMHC‑led initiatives. These amounts are not included above.

Source: Adapted from various public sources and documents provided by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada

Text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of $78.5 billion in planned spending under the National Housing Strategy (amounts are in millions of dollars).

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Infrastructure Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, provinces, and territories receive funding under the strategy for the following programs:

- National Housing Co‑Investment Fund is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $13,851,000,000.

- Legacy funding for social housing is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $11,170,000,000.

- Rapid Housing Initiative is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $2,544,000,000.

- Federal Community Housing Initiative is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $618,000,000.

- Federal Lands Initiative is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $202,000,000 in provincial and territorial funding.

- Canada Community Housing Initiative is a program that planned to spend $8,600,000,000 in federal, provincial, and territorial funding. The program is administered by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, provinces, and territories.

- Of this, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation planned to spend $4,300,000,000, and the provinces and territories planned to spend $4,300,000,000.

- Canada Housing Benefit is a program that planned to spend $4,315,000,000 in federal, provincial, and territorial funding and is administered by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, provinces, and territories.

- Of this, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation planned to spend $2,315,000,000, and the provinces and territories planned to spend $2,000,000,000.

- Reaching Home program and Homelessness Partnering Strategy is a program that planned to spend $3,524,000,000 in funding and is facilitated by Infrastructure Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada.

- The provinces and territories planned to spend $1,127,000,000 in other funding that they provided.

- Other CMHC‑led initiatives planned to spend $32,544,000,000.

Rental housing units considered affordable and approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund were often unaffordable for low-income households across Canada in 2020

Text version

This map of Canada shows the percentage of before‑tax income that would be spent on rent in each province and territory in 2020. For each province and territory, the maps shows whether rent would be affordable or unaffordable for low‑income households, according to data from 2020. The map shows that low‑income households would afford rent in 2 territories and 4 provinces and would not afford rent in 1 territory and 7 provinces.

A table under the map shows rent and income amounts rounded to the nearest $10. Amounts are based on data published at the national, provincial, and territorial levels.

According to Statistics Canada, low‑income households are defined as having after‑tax income of less than half of the median after‑tax income (for example, if median income is $50,000, the maximum income to be considered low income would be $25,000).

| Regions | Maximum annual before‑tax income for low‑income households that rentNote 1, Note 2, Note 3 | Maximum affordable monthly rentNote 2, Note 3 (less than 30% of before‑tax income) | Monthly rent at about 63% of median market rentNote 2, Note 3, Note 4 | Percentage of before‑tax income that would be spent on rent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Across Canada | $24,230 | $600 | $630 | 31.1% |

| Alberta | $28,690 | $710 | $720 | 30.1% |

| British Columbia | $28,540 | $710 | $820 | 34.3% |

| Manitoba | $21,130 | $520 | $660 | 37.6% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $22,280 | $550 | $530 | 28.6% |

| New Brunswick | $21,180 | $530 | $500 | 28.4% |

| Northwest Territories | $44,570 | $1,110 | $1,110Note 5 | 29.9% |

| Nova Scotia | $22,690 | $560 | $640 | 34.0% |

| Nunavut | $45,570 | $1,130 | $1,750Note 5 | 46.0% |

| Ontario | $25,860 | $640 | $800 | 37.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | $25,660 | $640 | $550 | 25.6% |

| Quebec | $21,810 | $540 | $490 | 26.7% |

| Saskatchewan | $24,710 | $610 | $630 | 30.5% |

| Yukon | $47,090 | $1,170 | $8105 | 20.7% |

|

Source: Based on data published by Statistics Canada and data published and provided by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation |

||||

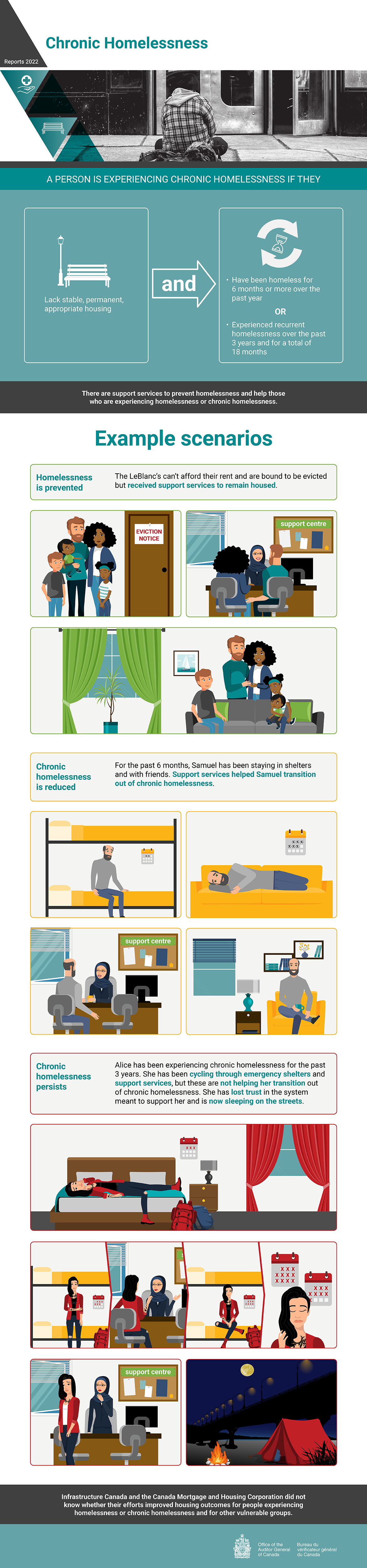

Infographic

Text version

A person is experiencing chronic homelessness if they lack stable, permanent, appropriate housing and have either been homeless for 6 months or more over the past year or experienced recurrent homelessness over the past 3 years and for a total of 18 months.

There are support services to prevent homelessness and help those who are experiencing homelessness or chronic homelessness.

Example scenarios

Three example scenarios are shown: homelessness is prevented, chronic homelessness is reduced, and chronic homelessness persists.

Homelessness is prevented

The LeBlancs can’t afford their rent and are bound to be evicted but received support services to remain housed.

Chronic homelessness is reduced

For the past 6 months, Samuel has been staying in shelters and with friends. Support services helped Samuel transition out of chronic homelessness.

Chronic homelessness persists

Alice has been experiencing chronic homelessness for the past 3 years. She has been cycling through emergency shelters and support services, but these are not helping her transition out of chronic homelessness. She has lost trust in the system meant to support her and is now sleeping on the streets.

Infrastructure Canada and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know whether their efforts improved housing outcomes for people experiencing homelessness or chronic homelessness and for other vulnerable groups.

Related information

Entities

Tabling date

- 15 November 2022

Related audits

- 2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 9—Investing in Canada Plan

Parliamentary hearings