2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 10—Securing Personal Protective Equipment and Medical Devices

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Assessing needs and managing the federal stockpile

- The Public Health Agency of Canada did not address long-standing federal stockpile issues

- The Public Health Agency of Canada oversaw the aspects of the warehousing and logistical support that it outsourced

- The Public Health Agency of Canada improved how it managed the assessment and allocation of personal protective equipment and medical devices to help meet provincial and territorial needs

- Procuring equipment and ensuring quality

- Health Canada modified its processing of supplier licence applications to respond more rapidly to increasing demand

- Public Services and Procurement Canada responded to the urgent need for equipment

- The Public Health Agency of Canada modified its quality assurance process to address the high volume of purchased equipment

- Assessing needs and managing the federal stockpile

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 10.1—Timeline of key events related to personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices from January 2020 to April 2020

- 10.2—Federal processes were used to help meet provincial and territorial needs for equipment to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic

- 10.3—Federal processes improved to assess needs and allocate equipment to the provinces and territories

- 10.4—Examples of medical devices and their classification

- 10.5—PPE and medical device contracts selected for examination

- 10.6—Procurement process streamlined during the COVID‑19 pandemic

- 10.7—Average number of calendar days to procure and deliver equipment to the Public Health Agency of Canada in the 39 contracts we examined

Introduction

Background

10.1 At the beginning of the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1 pandemic in early 2020, there was an extraordinary need for personal protective equipment (PPE)Definition 2 and medical devicesDefinition 3. These items help limit the spread of the virus, protect front-line workers, and keep patients severely affected by COVID‑19 alive. PPE and medical devices remain key to allowing the health care system to manage the pandemic.

10.2 During the early stages of the spread of the virus, there was unprecedented international competition for the same limited worldwide supply of PPE and medical devices (both referred to as equipment, where appropriate, in this report). In response, the federal government put a number of measures in place to help secure the national supply of equipment. The timeline of these measures, as well as key international events, is shown in Exhibit 10.1. The federal government reported that as of 31 December 2020, it had spent more than $7 billion on PPE and medical devices.

Exhibit 10.1—Timeline of key events related to personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices from January 2020 to April 2020

|

January 30 |

The World Health Organization declared the new coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern. |

|---|---|

|

March 3 |

The World Health Organization announced a global shortage of PPE and medical devices. |

| March 9 |

The federal government announced the intention to make bulk purchases of health care supplies, including PPE and medical devices. |

| March 11 |

The World Health Organization declared the global outbreak of COVID‑19 to be a pandemic. |

| March 12 |

Public Services and Procurement Canada issued a call to suppliers for PPE and medical devices. |

| March 13 |

A new COVID‑19 procurement team was created within Public Services and Procurement Canada. |

| March 14 |

A National Security Exception was invoked, giving Public Services and Procurement Canada the authority to use its emergency contracting authority to acquire goods and services required to respond to COVID‑19 using non-competitive processes until the end of the pandemic. |

| March 27 |

The first significant contract was awarded to a third-party service provider for warehousing and logistical support to accommodate the increased volume of PPE and medical devices being purchased. |

|

April 2 |

The federal, provincial, and territorial health departments collaborated to launch the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy (see paragraph 10.44 for more information on the strategy). |

Source: World Health Organization and various federal government sources

10.3 Provinces and territories are responsible for providing health care services, including managing their own equipment stockpiles. Various federal organizations play a role in helping provinces and territories secure additional equipment during public health emergencies.

10.4 Public Health Agency of Canada. The agency

- promotes health for Canadians

- prevents and controls chronic diseases

- prepares for and responds to public health emergencies

- strengthens intergovernmental collaboration on public health

10.5 The agency’s role in securing equipment needed in public health emergencies, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic, includes the following tasks. The agency

- manages the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile, which includes PPE and medical devices, to respond to a surge in demand for these items when provinces and territories exhaust their own stockpiles and to be the sole provider of items that are rare and difficult to obtain

- works with provincial and territorial governments to assess needs for equipment

- conducts quality assurance of the equipment it procures

- allocates and distributes equipment to provinces and territories and certain federal government organizations

10.6 Health Canada. The department helps Canadians maintain and improve their health. In the context of this audit, the department regulates the import and sale of medical devices and regulates and licenses suppliers of PPE and medical devices. It is also responsible for compliance monitoring and enforcement activities related to medical devices to verify that regulatory requirements are being adhered to.

10.7 Public Services and Procurement Canada. The department is the common service organization that purchases goods and services for federal departments and agencies. The department is coordinating purchases of commodities (including PPE and medical devices) on behalf of the Government of Canada.

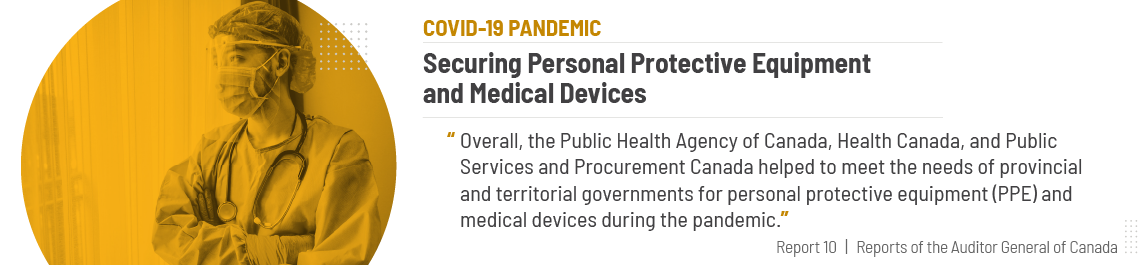

10.8 Responding to emergencies. In a public health emergency such as the COVID‑19 pandemic, these 3 federal organizations work together to help meet provincial and territorial needs for equipment. The process, which was modified to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic, is illustrated in Exhibit 10.2.

Exhibit 10.2—Federal processes were used to help meet provincial and territorial needs for equipment to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’sOAG’s review of documents provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada

Exhibit 10.2—text version

This flow chart shows the federal processes used to help meet provincial and territorial needs for equipment to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Provinces and territories need equipment.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) assesses the needs.

One of 2 federal processes is used.

In one process, PHAC distributes equipment from the federal stockpile in response to requests for assistance. The provinces and territories receive the equipment.

In the other process, the elements of bulk purchasing are used to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Health Canada licenses equipment and suppliers, and then Public Services and Procurement Canada purchases equipment. PHAC performs quality assurance. Then, it receives, allocates, and deploys equipment to the provinces and territories. The agency also replenishes the federal stockpile.

10.9 In September 2015, Canada committed to achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Helping to meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments for selected PPE and medical devices and providing adequate procurement support is related to target 3.d of the Sustainable Development Goals: “Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks.”

Focus of the audit

10.10 The audit focused on whether the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada, before and during the COVID‑19 pandemic, helped to meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments for selected PPE (N95 masks and medical gowns) and medical devices (testing swabs and ventilators). These items were selected because they were considered at risk for the following reasons:

- There was a limited pool of suppliers.

- The items had specific technical requirements.

- There was limited domestic production.

- There was high worldwide demand.

10.11 The audit also focused on whether Public Services and Procurement Canada provided adequate procurement support to the Public Health Agency of Canada. Circumstances such as worldwide supply shortages, increased prices for goods, and product quality issues are outside the control of the agency and the department and can cause delays in meeting provincial and territorial needs for equipment. Our audit work considered the impact of these delays on our findings and focused on aspects of the PPE and medical devices needs that were under the control of the agency and the department.

10.12 This audit is important because PPE and medical devices are vital for the safety of Canadians, particularly front-line workers and patients. This equipment is even more important during a pandemic. Management of the equipment has to be effective so that there is a sufficient supply when a public health emergency happens, and so that the infrastructure and processes are in place to meet increased demand during such emergencies.

10.13 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

10.14 In May 2021, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada also published the 2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Report 11—Health Resources for Indigenous Communities—Indigenous Services Canada. It focused on whether Indigenous Services Canada provided sufficient personal protective equipment, nurses, and paramedics to Indigenous communities and organizations in a coordinated and timely manner in order to protect Indigenous peoples against COVID‑19.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

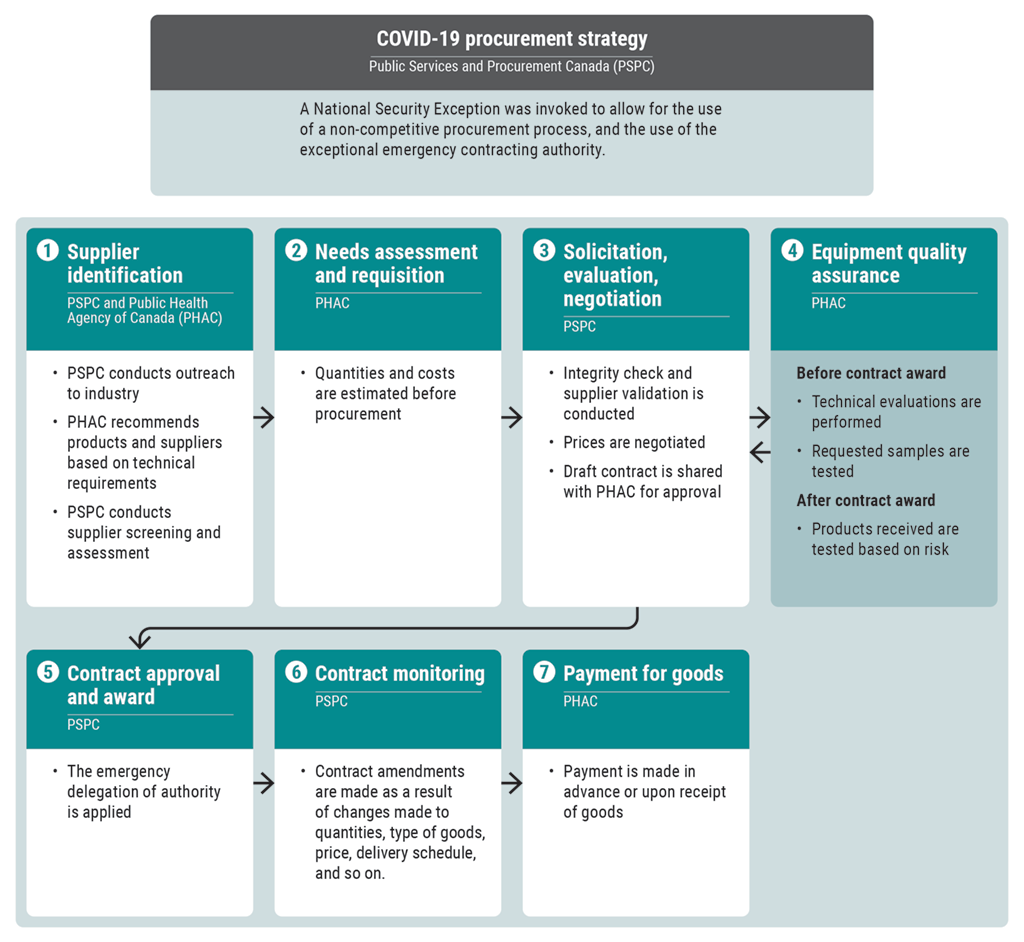

Overall message

10.15 Overall, the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada helped to meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments for personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices during the pandemic.

10.16 As a result of long-standing unaddressed problems with the systems and practices in place to manage the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile, the Public Health Agency of Canada was not as prepared as it could have been to respond to the surge in provincial and territorial needs for PPE and medical devices brought on by the COVID‑19 pandemic. However, when faced with the pressures created by the pandemic, the agency took action. We found that the agency improved how it assessed needs and purchased, allocated, and distributed equipment. For example, the agency quickly moved to bulk purchasing to meet the unprecedented demand for PPE and medical devices, and it outsourced much of the warehousing and logistical support it needed to deal with the exceptional volume of purchased equipment.

10.17 Also facing the pressures created by the pandemic, Health Canada modified its processing of equipment supplier licence applications to help keep up with the rapidly increasing demand for licences, and the Public Health Agency of Canada adjusted its quality assurance process to address the large volume of equipment needing to be assessed.

10.18 Similarly, Public Services and Procurement Canada mobilized resources and modified its procurement activities to quickly buy the required equipment on behalf of the Public Health Agency of Canada to respond to the pandemic. The department accepted some risks in order to procure large quantities of equipment in a market where the supply could not always meet demand. Otherwise, fewer pieces of equipment would have been available to provinces and territories.

Assessing needs and managing the federal stockpile

The Public Health Agency of Canada did not address long-standing federal stockpile issues

10.19 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada did not address long-standing issues in how personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices were managed in the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile. For example, separate from what it did to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the agency did not have a process to establish how much of an inventory of this equipment should be stockpiled to help meet provincial and territorial needs during a public health emergency.

10.20 We found that the unaddressed federal stockpile issues had been brought to the agency’s attention through a series of internal audits dating back to at least 2010. In our view, this calls into question the effectiveness of the agency’s governance and oversight of the federal stockpile before the World Health Organization declared COVID‑19 to be a pandemic in March 2020. As a result, the Public Health Agency of Canada was not as prepared as it could have been to help meet provincial and territorial needs.

10.21 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

10.22 This finding matters because emergencies such as the COVID‑19 pandemic can occur at any time with little warning. These events may require timely access to essential provisions in the federal stockpile, such as an inventory of PPE and medical devices based on expert advice, to help protect the health and safety of Canadians.

10.23 The federal government created the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile in the 1950s to protect Canadians from threats posed during the Cold War. Since then, the role of this federal stockpile has evolved. Today’s federal stockpile aims to have the items needed to help provinces and territories respond rapidly to public health emergencies when there is a surge in demand beyond their own stockpiles. Another objective of this federal stockpile is to be the sole provider of items that are rare and difficult to obtain in a timely manner or are used in low-probability, high-impact national emergencies. The National Emergency Strategic Stockpile consists of 3 main categories of items: pharmaceuticals, pandemic and social service supplies, and medical equipment and supplies.

10.24 Decisions to provide National Emergency Strategic Stockpile assets to federal departments are to be made on a case-by-case basis. Federal departments are to maintain their own modest stockpiles to fulfill their departmental requirements.

10.25 In 2010, the Public Health Agency of Canada conducted an internal audit on emergency preparedness. This audit had several significant findings related to the management of the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile.

10.26 In 2013, the agency conducted a follow-up internal audit and found that the federal stockpile issues raised in the 2010 internal audit had not been fully addressed.

10.27 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 10.38.

Inadequate governance and oversight

10.28 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada did not fully address significant findings about the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile from the agency’s 2010 and 2013 internal audits, despite management’s commitment to do so. These significant findings remain relevant today because they point to a lack of some of the systems and practices needed to properly manage and operate the federal stockpile. In our view, given the time that has elapsed since the need to develop and maintain such systems and practices was brought to the agency’s attention, we would have expected full implementation of these important recommendations by now.

10.29 For example, we found that information needed to govern, oversee, and manage the federal stockpile was missing, outdated, or lacked clarity. This had a negative impact on the operation of the federal stockpile, as discussed in paragraphs 10.34 through 10.37. As a result, the agency was not as prepared as it could have been to respond to provincial and territorial government needs.

10.30 We found that, consistent with a finding from the 2010 internal audit, the agency did not know whether certain objectives for the federal stockpile were being met. The agency had yet to develop a results-based management framework specific to the federal stockpile, including clearly defined performance measures for relevance, reliability, and timeliness.

10.31 In response to the 2010 internal audit, the agency developed the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile policy in 2012 to clarify the stockpile’s role and objective. We found that, despite the requirement for “regular updates,” the policy had not been updated since its development, and contained outdated information.

10.32 The National Emergency Strategic Stockpile optimization plan outlines governance and authorities, as well as the composition, deployment, management, and procurement of inventory. We found that it too had not been updated since its development in 2013 and included outdated and unclear information.

10.33 The National Emergency Strategic Stockpile memoranda of understanding that set out federal, provincial, and territorial responsibilities were also outdated. We found that new memoranda were not finalized, despite the agency’s commitment to do so in response to a finding from the 2010 internal audit. This meant that updated federal, provincial, and territorial responsibilities for the federal stockpile—particularly those pertaining to information-sharing obligations—had not been formalized.

Lack of federal stockpile management

10.34 We found that there were long-standing unaddressed problems with the systems and practices to manage the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile’s inventory, dating back to at least 2010.

10.35 Before the pandemic, there was no rationale to justify the quantities of equipment held in the stockpile. Internal documents noted budget limitations. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada’s 2013 follow-up internal audit, management was developing a more comprehensive needs-based assessment process to justify federal stockpile acquisitions. No such process was in place for PPE and medical devices, and acquisitions were based on available budget.

10.36 We found that issues related to obsolete inventory and disposal that were raised in the 2010 internal audit report persisted. Some of the federal stockpile inventory was expired or outdated and the Public Health Agency of Canada did not track the age or expiry date of some items. This meant that essential information needed to ensure that inventory in the stockpile, including PPE and medical devices, was not obsolete or close to expiring could not be comprehensively monitored and acted upon.

10.37 The agency’s 2010 internal audit found significant deficiencies in the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile electronic inventory management system. For example, some inventory records were inaccurate and there was a lack of timely and relevant management information. Subsequent to this finding, the agency put in place 2 different systems to collectively track inventory. However, these systems did not fully address the deficiencies identified in 2010. In January 2020, the agency drafted a business case to develop 1 system in order to have a single, comprehensive approach to inventory management, including providing real-time data on the location of inventory. Agency officials told us that the business case was put on hold before the pandemic because of budget constraints, and later because of the need to respond to COVID‑19.

10.38 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should develop and implement a comprehensive National Emergency Strategic Stockpile management plan with clear timelines that responds to relevant federal stockpile recommendations made in previous internal audits and lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic.

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s response. Agreed. The Public Health Agency of Canada states that the experience of COVID‑19 has provided a lived experience of a global pandemic, the nature of which Canada has not seen in over 100 years. Recognizing that existing policies, practices, and resources were leveraged to guide the current response, lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic will inform how the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile is managed going forward.

The agency is currently working on a comprehensive management plan with associated performance measures and targets for the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile to support responses to future public health emergencies. This plan will focus on key areas such as optimizing life-cycle material management, enhancing infrastructure and systems, and working closely with provinces and territories and other key partners to better define needs and roles and responsibilities.

The agency will continue to identify and implement incremental improvements during its ongoing efforts to respond to COVID‑19. The agency is expecting to complete the comprehensive National Emergency Strategic Stockpile management plan with clear timelines for implementation within 1 year of the end of the pandemic.

The Public Health Agency of Canada oversaw the aspects of the warehousing and logistical support that it outsourced

10.39 During the pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada largely outsourced additional warehousing and logistical support for personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices to third-party service providers. This additional support was needed because of the unprecedented volume of equipment acquired to help meet provincial and territorial needs.

10.40 We found that to oversee the work done by these third-party service providers, the agency worked with a professional services firm to develop a tool that allowed for monitoring and reporting on the flow of equipment to provinces and territories. However, there were inventory control challenges, such as sometimes being unable to correctly track items. In addition, some of the contracts with third-party service providers did not include service standards to signal when a delay in the flow of goods to provinces and territories required follow-up.

10.41 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

10.42 This finding matters because the Public Health Agency of Canada remains accountable for the management of the equipment it procures to help meet provincial and territorial needs even when using third-party service providers.

10.43 In March 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada launched a bulk purchasing process by placing large orders for equipment to help meet the needs of provinces and territories through Public Services and Procurement Canada.

10.44 On 2 April 2020, the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy was endorsed by federal, provincial, and territorial ministers of health. The strategy formalized how products received under bulk purchasing efforts should be allocated. According to the strategy, once products were purchased and ready to be delivered,

- 80% would be distributed to provinces and territories proportionally to their respective populations

- 18% would be allocated to the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile

- 2% would be allocated to Indigenous Services Canada for Indigenous peoples

10.45 To accommodate the increased volume of equipment it procured through the bulk purchasing process, the agency significantly expanded its warehouse space. The number of sites increased from the original 8 federally managed warehouses that were used to store the federal stockpile to 19 warehouses. This represented an increase of approximately 167,000 square metres. Most of these additional warehouses were owned and managed by third-party service providers that provided both space and logistical assistance.

10.46 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 10.51.

Oversight of third-party warehousing and logistics

10.47 We found that in April 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada worked with a professional services firm to develop a tool that allowed for monitoring and reporting on the flow of equipment to provinces and territories. This tool also enabled the agency to oversee performance of third-party warehousing and logistics service providers.

10.48 Provinces and territories were given access to the monitoring and reporting tool. This tool allowed them to see shipment data for their respective jurisdictions. Agency officials told us that the tool evolved over time to respond to the information needs of the provinces and territories.

10.49 Third-party warehousing and logistics service providers were required to submit specific information for the agency to include in its electronic inventory management system, as well as in its monitoring and reporting tool. However, we found that not all third-party service providers could abide by these requirements because of, for example, incomplete information from suppliers and constraints imposed by the agency’s system. This absence of specific information contributed to the agency’s ongoing inventory control challenges. For example, the agency was sometimes unable to correctly track items. Officials told us that they tried to address these challenges through frequent communication, warehouse site visits, and training.

10.50 Agency officials also told us they did daily monitoring to make sure equipment was distributed to provinces and territories as required. We found that service standards for delivery were not included in some contracts. The agency addressed the need for the inclusion of service standards over time. These service standards were part of the long-term contract with a warehousing and logistics service provider signed in September 2020.

10.51 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should enforce, as appropriate, the terms and conditions in its contracts with third-party warehousing and logistics service providers—including the long-term contract signed in September 2020—for the provision of timely, accurate, and complete data to help control inventory of personal protective equipment and medical devices.

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s response. Agreed. Since the long-term contracts were established, the Public Health Agency of Canada continues to work closely with its third-party warehousing and logistics service providers for the provision of timely, accurate, and complete data to help control personal protective equipment and medical devices and, if required, will take appropriate actions to enforce the terms and conditions in these contracts.

The Public Health Agency of Canada improved how it managed the assessment and allocation of personal protective equipment and medical devices to help meet provincial and territorial needs

10.52 We found that, as the pandemic evolved, the Public Health Agency of Canada improved how it managed the assessment of provincial and territorial needs for personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices and how it allocated equipment to help meet those needs. The agency moved from reactive management to informed planning and allocation. An initial shift to a bulk purchasing strategy allowed the agency to help meet the unprecedented need for equipment across the country. Meeting needs was also fostered by strengthened collaboration and communication among the agency and other federal organizations, provinces, and territories as the pandemic continued.

10.53 We found that in August 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada began to use a new, long-term national supply and demand model, whose development was led by Health Canada during the summer of 2020. This model provided data that helped the agency to make purchasing decisions.

10.54 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

10.55 This finding matters because the federal government needs to help address the most urgent needs of provinces and territories for PPE and medical devices within a global context where the supply of those items is scarce.

10.56 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

Improved management of needs assessment and allocation decision making

10.57 We found that, during the pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada improved its processes to assess needs and make allocation decisions. As a result, the agency was better able to understand and help meet provincial and territorial needs for PPE and medical devices. The processes became more rigorous, moving from reactive management to informed planning. We also found that a new, long-term supply and demand model provided data that helped the agency to make purchasing decisions.

10.58 Nationwide concerns about the virus increased in late January and early February 2020. In response, committees, with participation from the federal, provincial, and territorial governments, met to get and share information about existing provincial and territorial equipment stockpiles, anticipated pressures, and needs for equipment. We found that the agency had difficulty accurately assessing overall national demand because of initial communication challenges with the provinces and territories. However, collaboration and communication among federal organizations, provinces, and territories was strengthened as the pandemic continued, which contributed to the federal government being better able to identify and help meet needs.

10.59 In February 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada received the first direct request for assistance from a province or territory for equipment in its National Emergency Strategic Stockpile. Such direct requests for assistance were also possible before the pandemic, but few were received.

10.60 In March 2020, the agency launched a bulk purchasing process by placing large orders for equipment to help meet the needs of provinces and territories through Public Services and Procurement Canada. The agency did this because there were significant problems with the global supply chain that required bulk purchasing power to order equipment.

10.61 On 2 April 2020, the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy was endorsed by federal, provincial, and territorial ministers of health. The strategy was developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada in collaboration with federal, provincial, and territorial partners. The strategy formalized how products received under bulk purchasing efforts should be allocated. Bulk purchasing was led by the federal government, with input from the provinces and territories, to proactively and more rapidly buy equipment for front-line health care workers. In our view, the agency’s shift from processing individual provincial and territorial requests for assistance to bulk purchasing was necessary to reduce the risk of supply shortages and to help manage the pandemic response (Exhibit 10.3).

Exhibit 10.3—Federal processes improved to assess needs and allocate equipment to the provinces and territories

| Key dates | Requests for assistance from the provinces and territories | Bulk purchasing | Tracking and reporting tools |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Before 2020 |

|

|

|

|

January to March 2020 |

|

|

|

|

2 April 2020: Launch of Allocation of Scarce Resources–COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy |

|

|

|

|

April to August 2020 |

|

|

|

Source: Based on the OAG’s review of documents provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada

10.62 According to the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy, once products were purchased and ready to be delivered, 80% would be distributed to provinces and territories proportionally to their respective populations (see paragraph 10.44). The Public Health Agency of Canada submitted bulk item requisitions to Public Services and Procurement Canada on the basis of estimated provincial and territorial needs. We found that, in some cases, Public Services and Procurement Canada made contracts for much larger or smaller quantities than originally requisitioned. We were told that this happened because federal organizations made adjustments to purchases on the basis of reviews of equipment to help determine appropriate quantities to buy to help meet demand. Public Services and Procurement Canada sometimes opted to buy larger quantities when supply was available or when the department had previously been unable to fulfill a complete order because supply was low or inaccessible at that time. From April to June 2020, equipment was acquired on an urgent basis and suppliers were followed up with to confirm delivery schedules. Orders were staggered over time, and distribution depended on product availability.

10.63 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada partnered with other federal government organizations to collect and integrate data on equipment acquisition and deployment. This data included quantities ordered, expected delivery dates, and quantities received. The data was used in various reporting tools to provide real-time tracking of the supply of equipment, including in a national equipment dashboard. The dashboard was published daily by Health Canada and Statistics Canada and used by federal partners, provinces, and territories. The data was also used for other reporting tools to inform the supply of equipment.

10.64 If provinces and territories had an urgent need that could not be met with their allocation of equipment purchased in bulk through the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy, they could continue to submit requests for assistance to the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile. We found that the agency was able to help meet these urgent provincial and territorial needs in part because the federal stockpile was allocated 18% of items obtained through bulk purchasing. We found that under the strategy, the process for the Public Health Agency of Canada to assess these requests became more refined, and priority was determined mainly on the basis of urgency. Provincial and territorial requests were triaged and filled on the basis of the availability of equipment in the federal stockpile. In cases where a request was declined or only partially met, the province or territory could make another request later or explore other options, such as requesting aid from another province or territory. The agency also revisited needs weekly as more equipment became available.

10.65 We found that the development of a long-term national supply and demand model, led by Health Canada, was key to the shift from reactive management to informed planning and allocation. By May 2020, involved federal departments, including the Public Health Agency of Canada, realized that a long-term model with provincial and territorial input was needed to project supply and demand for equipment for the next 12 to 18 months. The federal government contracted with the private sector to build this model, under Health Canada’s leadership. Health Canada received weekly data from the provinces and territories on their own inventory levels, usage rates, and future orders. This data was essential to ensure the model’s accuracy.

10.66 The new national supply and demand model projected different disease progression scenarios by province and territory. These scenarios, along with data from multiple sectors in each province and territory, such as data on how equipment is used, became the basis for projecting future demands for equipment. The demand projections were then compared against supply data to identify future equipment shortages over at least the next 12 months across multiple sectors in each province and territory. Officials told us that, starting in August 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada used data from this model to assess whether additional purchasing of equipment was required.

Procuring equipment and ensuring quality

Health Canada modified its processing of supplier licence applications to respond more rapidly to increasing demand

10.67 We found that Health Canada modified its processing of licence applications from personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical device suppliers so it could process the surge of applications more rapidly. The department issued temporary submission numbers for medical device establishment licences to suppliers until their applications could be fully reviewed and decisions made. We found that this new approach to processing establishment licence applications helped the department manage nearly double the number of applications it had received in the previous year.

10.68 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Risk-based changes to processing licence applications

- Appropriate action to address substandard respirators

10.69 This finding matters because many Canadians use PPE and medical devices, and they expect these products to be safe, effective, and available when needed.

10.70 All medical devices sold in Canada, including PPE sold for medical use, are subject to licensing requirements. PPE and medical devices are categorized into 4 classes on the basis of the risk associated with their use (Exhibit 10.4). Class I medical devices are the lowest risk. Class IV medical devices are the highest risk.

Exhibit 10.4—Examples of medical devices and their classification

| Risk | Classification | Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Lowest to Highest |

Class I |

N95 masks, medical gowns, testing swabs |

|

Class II |

Medical gloves |

|

|

Class III |

Ventilators |

|

|

Class IV |

Pacemakers |

10.71 As the country’s regulator of the import and sale of PPE and medical devices, Health Canada issues 2 types of licences:

- Medical device establishment licences—These licences are issued to Class I PPE and medical device manufacturers, as well as importers or distributors of all 4 classes of PPE and medical devices. They are issued on the basis of an attestation about requirements related to documented procedures for complaint handling, distribution records, recalls, and problem reporting.

- Medical device licences—These licences are issued for specific Class II, III, and IV PPE and medical devices and are issued to the manufacturers of those devices. They are issued on the basis of a review to ensure the device meets regulatory requirements, including requirements for safety and effectiveness. The level of review required increases as the medical device risk classification increases. The manufacturer may sell the licensed device directly or through a holder of a medical device establishment licence.

10.72 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 10.82.

Risk-based changes to processing licence applications

10.73 We found that Health Canada modified its processing of applications for medical device establishment licences to respond more quickly to a surge of applications from suppliers wanting to sell PPE and medical devices. These measures helped the department to manage nearly double the number of establishment licences during our 8-month audit period than it normally handles annually. These establishment licences included those for suppliers providing PPE and medical devices to meet provincial and territorial needs.

10.74 In April 2020, to deal with the increased demand for licences, Health Canada issued temporary medical device establishment licence submission numbers to applicants that provided contact and medical device information in their applications. The submission numbers were valid until the department could conduct a comprehensive review of the applications and make a decision about licensing. While waiting for a decision, these applicants were allowed to import and sell medical devices in Canada. The temporary submission number process was put in place to try to achieve a 24-hour turnaround time during a period of high demand for licences. Before the pandemic, the average processing time for new establishment licence applications was 39 days.

10.75 Health Canada indicated that enforcement discretion was applied in relation to the licensing requirements for the importation and sale of medical devices. Although the department’s approach was practical in the circumstances, in our view, the more appropriate measure would have been for the Minister of Health to issue an interim order under section 30.1 of the Food and Drugs Act to temporarily waive and change mandatory regulatory requirements. This statutory process provides transparency and clarity because the interim orders are required to be tabled in Parliament.

10.76 We found that to mitigate the increased risks of providing temporary submission numbers, the department had processes in place to

- inform applicants of expectations to meet the requirements of licence holders

- seize, stop sale, or prevent further imports of products

- take immediate compliance and enforcement action if a health risk was identified

10.77 We found that, to respond to evolving circumstances, the department continually updated and communicated changes to the processing of licence applications to its employees. In our opinion, this communication was important, because some staff had been redeployed from other divisions to help process the surge of applications.

Appropriate action to address substandard respirators

10.78 We noted that, as a Class I medical device, respiratorsDefinition 4 could be sold in Canada under a medical device establishment licence. This meant that while a company was licensed to sell the respirators, the respirators themselves were not licensed and therefore were not subject to a review by Health Canada for safety and effectiveness.

10.79 In May 2020, the United StatesU.S. Food and Drug Administration issued revised guidance to stakeholders indicating that certain respirators may not provide adequate protection. We found that Health Canada took appropriate action to determine and address the impact of these products in Canada. In particular, it issued a public recall notice listing the respirator products that did not meet performance standards. The department regularly updated this list and asked suppliers to conduct a voluntary recall of the products listed. By the end of our audit period, the list included 165 respirator products.

10.80 We found that, in addition to issuing the recall notice, Health Canada also searched its database of suppliers. The department communicated with suppliers that may have been selling recalled respirators to determine whether they were affected, and directed them to take appropriate action. We found that the department added measures in order to mitigate the risk of other suppliers selling recalled products. These measures included communicating recall information to all suppliers and conducting continual screening of its supplier database for recalled products.

10.81 In our view, a review of whether respirators are appropriately classified is warranted given

- the importance of respirators when responding to infectious diseases such as COVID‑19

- the demonstrated lack of effectiveness of a large number of these products

- the fact that as a Class I device, respirators are not subject to a Health Canada review for safety and effectiveness

10.82 Recommendation. Health Canada should determine whether respirators are appropriately classified given that Class I medical devices are not subject to a Health Canada review for safety and effectiveness.

Health Canada’s response. Agreed. While Health Canada currently regulates medical devices in accordance with a risk-based classification system, consideration could be given to providing greater pre-market oversight over some lower-risk devices. Health Canada acknowledges the challenges associated with ensuring that the safety, effectiveness, and quality requirements for respirators are met in situations such as the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Under the existing Medical Devices Regulations, a pre-market evaluation is not an option for Class I medical devices. However, under the interim order (IO) pathway, Health Canada was afforded regulatory flexibilities allowing for pre-market review of respirators. Post-market surveillance activities, including inspections, and scientific evaluations under the IO, increased Health Canada’s awareness of low-quality respirators that have the potential to enter the Canadian market.

Health Canada will specifically review the classification of lower-risk devices, including respirators, in the context of the development of Agile Regulations for Medical Devices. While in its infancy, this initiative is underway and will provide an opportunity to determine whether respirators are appropriately classified. Health Canada is committed to exploring options to evaluate the appropriate level of pre-market oversight of these devices. An issue analysis will be conducted within 1 year of the end of the pandemic.

Public Services and Procurement Canada responded to the urgent need for equipment

10.83 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada quickly adapted its procurement activities to buy personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices on behalf of the Public Health Agency of Canada to respond in a timely manner to the COVID‑19 pandemic. We also found that, while reacting to an emergency situation, the department accepted some additional risks by paying some suppliers in advance in a very competitive environment without always assessing their financial viability.

10.84 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Rapid modification to procurement processes

- Timely awarding of contracts

- Acceptance of some procurement risks

10.85 This finding matters because effective procurement was important to helping fulfill provincial and territorial needs for equipment—getting the right quality and quantity quickly.

10.86 Before the pandemic, Canada had very limited domestic capacity to produce PPE and medical devices and, therefore, relied on imports. At the beginning of the pandemic, there was an exponential increase in worldwide demand for the same equipment, which drastically affected global supply. The limited supply made the market for this equipment very competitive and resulted in increased prices. In such an environment, advance payments were sometimes required by suppliers. There were also challenges to secure sufficient cargo space on planes to urgently transport goods to Canada, and logistics services were put in place to take possession of the equipment earlier in the delivery chain.

10.87 During our audit period, Public Services and Procurement Canada awarded, on behalf of the Public Health Agency of Canada, a total of 85 contracts for selected PPE and medical devices, totalling $3.7 billion. We examined 39 of these contracts. Exhibit 10.5 lists these contracts by type of equipment and their value.

Exhibit 10.5—PPE and medical device contracts selected for examination

| Equipment type | Number of contracts examined | Value including taxes (in millions) |

|---|---|---|

| N95 masks | 10 | $380 |

| Medical gowns | 14 | $890 |

| Test swabs | 7 | $67 |

| Ventilators | 8 | $633 |

| Total | 39 | $1,970 |

10.88 The procurement process that Public Services and Procurement Canada streamlined to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic is illustrated in Exhibit 10.6.

Exhibit 10.6—Procurement process streamlined during the COVID‑19 pandemic

Source: Based on the OAG’s review of documents provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada

Exhibit 10.6—text version

This flow chart shows Public Services and Procurement Canada’s streamlined procurement process to purchase equipment during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

For the COVID‑19 procurement strategy established by Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), a National Security Exception was invoked to allow for the use of a non-competitive procurement process, and the use of the exceptional emergency contracting authority.

Step 1 is supplier identification, where PSPC and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) both have roles to play. PSPC conducts outreach to the industry. PHAC recommends products and suppliers based on technical requirements. PSPC conducts supplier screening and assessment.

Step 2 is needs assessment and requisition, which is conducted by PHAC. Quantities and costs are estimated before procurement.

Step 3 is solicitation, evaluation, and negotiation, which is conducted by PSPC. An integrity check and supplier validation is conducted. Prices are negotiated. A draft contract is shared with PHAC for approval.

Step 4 is equipment quality assurance, which is conducted by PHAC. Before a contract is awarded, technical evaluations are performed and requested samples are tested. After a contract is awarded, products received are tested based on risk.

After step 4, step 3 is repeated as needed, and then the process moves to step 5.

Step 5 is contract approval and award, which is conducted by PSPC. The emergency delegation of authority is applied.

Step 6 is contract monitoring, which is conducted by PSPC. Contract amendments are made as a result of changes made to quantities, type of goods, price, delivery schedule, and so on.

Step 7 is payment for goods, which is conducted by PHAC. Payment is made in advance or upon receipt of goods.

10.89 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 10.102.

Rapid modification to procurement processes

10.90 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada quickly modified its procurement processes at an early stage of the pandemic to allow for the use of its emergency contracting authority.

10.91 To speed up the purchase of goods and services needed to respond to the pandemic, several measures were taken, such as the following:

- The National Security Exception was invoked, effective until the end of the pandemic, to allow Canada to exclude its procurement from some or all of the obligations under specific trade agreements. As a result, Public Services and Procurement Canada was not required to follow specific procedural and market access obligations.

- Public Services and Procurement Canada exercised its emergency contracting authority to acquire goods using non-competitive processes.

- The Treasury Board increased Public Services and Procurement Canada’s departmental limit for emergency contracting from $15 million to $500 million. This limit was increased to improve the department’s ability to secure pandemic supplies, including PPE and medical devices, faster without having to get Treasury Board approval.

- Public Services and Procurement Canada approved a new internal exceptional emergency delegation of authority. This authority allowed department executives below the assistant deputy minister level to approve COVID‑19–related contracts.

10.92 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada staff were quickly reassigned from other sectors in the department to address immediate procurement needs related to the COVID‑19 pandemic. The department later dedicated permanent resources to respond to longer-term procurement needs for this equipment.

Timely awarding of contracts

10.93 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada’s streamlined procurement processes and strategies resulted in timely awarding of contracts to buy equipment.

10.94 The average time it took to award the 39 contracts we examined, and the average time it took from the execution of the original contract to the first order delivered at the Public Health Agency of Canada, is illustrated in Exhibit 10.7.

Exhibit 10.7—Average number of calendar days to procure and deliver equipment to the Public Health Agency of Canada in the 39 contracts we examined

| Equipment type | Average number of days from requisition to contract signature (Public Services and Procurement Canada’s responsibility) |

Average number of days from original contract signature to first delivery (Supplier’s responsibility) |

Total number of days |

|---|---|---|---|

| N95 masks | 34 | 71 | 105 |

| Medical gowns | 28 | 57 | 85 |

| Test swabs | 8 | 16 | 24 |

| Ventilators | 22 | 132 | 154 |

Source: Based on the OAG’s review of documents and data provided by Public Services and Procurement Canada

10.95 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada awarded contracts relatively quickly, considering that the department needed to contact suppliers, negotiate terms and conditions, and get approval from senior officials. Because of exceptional circumstances related to the COVID‑19 pandemic and the need to use non-competitive purchasing processes, it was not appropriate to compare these results with the department’s usual procurement times.

10.96 We also looked at the time it took from the approval of the original contract to the first delivery to show the result of the work done, knowing that the delivery of goods is the suppliers’ responsibility. The figures in the third column of Exhibit 10.7 include any amendments made to terms and conditions since the approval of the original contract to change quantities or delivery schedule. They also include the time needed to manufacture the equipment because not all equipment was in stock. In many cases, to increase domestic production, production processes had to be modified or set up to manufacture equipment in Canada, which added time to the equipment delivery dates. Finally, the figures include the time needed to ship the equipment to the warehouses used by the Public Health Agency of Canada to store it.

Acceptance of some procurement risks

10.97 In April 2020, Public Services and Procurement Canada identified some new risks, such as reduced oversight, which could result in errors being made or procurement decisions being insufficiently documented. We found that these risks were not offset by any planned mitigation strategy. As a result, while the department was able to speed up the procurement process, it could not always demonstrate that it exercised the needed oversight.

10.98 We found that the department could not always demonstrate that its officials properly followed the new emergency delegation of authority. In 41% of the original contracts examined (16 out of 39), the documentation did not show whether approval was given at the appropriate level of authority. However, we found significant improvement in the way contract approvals were documented between May and August 2020 compared with contracts prepared between March and April 2020.

10.99 We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada had performed an integrity verification of each supplier that was awarded a contract according to the Government of Canada’s Integrity Regime. This verification includes a review of databases, open source information, and corporate information. However, we found that in 59% of the cases (23 out of 39), this verification was done only after the contract was awarded. To mitigate the risk posed by this timing of the verification, Public Services and Procurement Canada established terms and conditions to ensure that it could terminate a contract if the supplier did not satisfy the requirements of the government’s integrity regime.

10.100 To acquire goods in an environment where supply was limited, Public Services and Procurement Canada often had to pay in advance. As outlined in the Treasury Board’s Directive on Payments, advance payments are to be issued in exceptional circumstances only. Because of the pandemic, advance payment was made in 36% of the contracts we examined (14 out of 39). These contracts are considered riskier, since the government might pay for goods it does not receive. We found that the value of the advance payments made in the contracts we examined ranged from 20% to 80% of the original contract value and totalled $618 million. We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada took steps to recover amounts that were paid in advance when no goods were received.

10.101 We found that the department could not always demonstrate that it conducted specific assessments for contracts subject to advance payment, to ensure, for example, the suppliers’ financial viability. A financial evaluation of suppliers was done in 50% (7 out of 14) of the contracts we examined where payment was issued in advance. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Guide to Advance Payments states that before including an advance payment clause in a contract, a risk assessment should be conducted. Such a risk assessment would provide the department with information on, for example, the supplier’s viability and the risk of the contract not being fulfilled.

10.102 Recommendation. Public Services and Procurement Canada, while addressing urgent needs and accepting procurement risks, should conduct checks of the financial strength of suppliers before awarding contracts that involve advance payment.

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. The audit acknowledges that Public Services and Procurement Canada mobilized its workforce and adapted quickly to deliver on urgent procurement requirements for Canadians. Procuring the goods and services required to combat the pandemic, particularly in the first 100 days (the focus of this audit), was an around-the-clock effort, undertaken in an unprecedented environment of extremely tight global supply chains. This presented challenges ranging from being able to action contracts outside of regular business hours, address logistics, and undertake new critical activities such as the Essential Services Contingency Reserve. While the department established processes at the outset of the pandemic aimed at ensuring oversight and due diligence processes, we recognize that procurement processes can always be improved, and in the context of advance payments, this includes undertaking financial checks. Over the course of the last year, the department has continuously evolved its approaches. Going forward, the department will further update its processes related to emergency procurements to address lessons learned through the course of this audit and other exercises, while continuing to prioritize the health and safety of Canadians.

The Public Health Agency of Canada modified its quality assurance process to address the high volume of purchased equipment

10.103 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada appropriately modified its quality assurance processes to respond to the high volume of personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices ordered from new suppliers. Furthermore, we found that the agency rapidly established capacity to perform quality assurance testing on equipment.

10.104 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

10.105 This finding matters because Canadians expect PPE and medical devices to be safe and effective.

10.106 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

Adequate modifications to quality assurance processes

10.107 We found that, in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada adequately modified its quality assurance processes for PPE and medical devices. In April 2020, the agency created and led a technical assessment committee to establish technical specifications for COVID‑19–related equipment on the basis of internationally recognized standards. The resulting technical specifications were made public through a government website. The committee assessed the specific products considered for purchase. The agency then recommended whether Public Services and Procurement Canada should award a contract.

10.108 We also found that, in April 2020, the agency modified its quality assurance process for N95 masks, medical gowns, and testing swabs to minimize delays by introducing a risk-based system. This risk-based system was established to deal with the high volume of equipment received from suppliers from whom the Government of Canada had not previously purchased.

10.109 We found that the risk-based quality assurance process minimized testing delays for N95 masks, testing swabs, and medical gowns. The system ranked suppliers by their history of conformity with product specifications, as well as by a risk level assigned to the product itself. All suppliers had to provide product and packaging photographs along with a declaration of conformity with specifications. Product testing was mandatory for suppliers unknown to the Government of Canada and for suppliers that had not provided enough evidence that their products conformed to specifications. Testing was optional for suppliers with a history of compliance.

10.110 When N95 masks, medical gowns, and testing swabs failed testing, the Public Health Agency of Canada considered a number of options. For example, products could have been relabelled and allowed to be distributed for a non-medical purpose after consultation with Health Canada and the manufacturer. Alternatively, the agency could have rejected the product shipment and advised the department to request a replacement or cancel the contract.

10.111 The testing of ventilators followed a different quality assurance process. We found that this process was based on rigorous quality thresholds. This process did not change during the pandemic. It was important to test ventilators thoroughly because of the increased risk to the health of the patients using them. Ventilators that did not pass testing because of major defects were returned to the supplier. When minor issues were identified, replacement parts were provided by the supplier and the units were retested.

Rapid increase of equipment testing capacity

10.112 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada was able to rapidly increase testing capacity for the 4 types of PPE and medical devices we examined. The agency added specialized expertise to meet the high demand for product testing because of increased volumes of equipment purchased. We also found that domestic testing capacity for N95 masks was increased during this period. For example, the National Research Council Canada established facilities in Ottawa to evaluate N95 masks, and private and provincial labs were contacted to establish a testing laboratory network across the country and increase overall testing capacity.

Conclusion

10.113 We concluded that the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada helped meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments to obtain selected personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices during the pandemic.

10.114 As a result of long-standing unaddressed problems with the systems and practices in place to manage the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile, the Public Health Agency of Canada was not as prepared as it could have been to respond to the surge in provincial and territorial needs brought on by the COVID‑19 pandemic. During the pandemic, the agency improved how it assessed, allocated, and distributed PPE and medical devices. Health Canada and the agency also modified their licensing application and testing processes, respectively, to better respond to the increased demand for equipment.

10.115 In a market where the supply could not always meet demand, Public Services and Procurement Canada procured large quantities of PPE and medical devices by mobilizing resources and modifying processes. In addition, to get this equipment to provinces and territories quickly, the department accepted some procurement risks.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on securing personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical devices. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada, before and during the COVID‑19 pandemic, helped meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments for selected personal protective equipment and medical devices, and whether Public Services and Procurement Canada provided adequate procurement support.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on the actions taken by the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada to help meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments for selected PPE and medical devices. The audit also examined the actions taken by Public Services and Procurement Canada to procure this equipment.

We examined data pertaining to the full scope of helping to meet the needs of provinces and territories for PPE and medical devices for context and to conclude on information sharing between relevant federal organizations and provinces and territories. However, the bulk of our analysis was focused on the 4 types of equipment selected for detailed examination: N95 masks, medical gowns, testing swabs, and ventilators.

We did not examine the procurement of equipment for federal organizations that was significantly lower in volume and in value than the equipment procured to help meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments.

Various circumstances and available resources affecting the ability to help meet needs for PPE and medical devices were outside the Public Health Agency of Canada’s control during the pandemic—such as the availability and price of this equipment during the pandemic. Audit work took these circumstances into account. We assessed other impediments to helping to meet the needs for this equipment, such as the speed with which the virus spread and logistical challenges with which agency and department officials had to contend.

Using a combination of data analytics, representative sampling, and detailed file review, we examined 39 contracts for selected PPE and medical devices from Public Services and Procurement Canada’s data management system as of 31 August 2020. The contracts we examined were initiated between 1 January 2020 and 31 August 2020 (including amendments and changes made until 31 December 2020). The contracts were further divided according to the 4 types of equipment examined in this audit. We randomly selected contracts to obtain a representative sample of the entire population. This sample was tested to ensure a 90% confidence level with a 10% margin of error. This audit contributed to Canada’s actions in relation to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 3—Good health and well-being.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada, before and during the COVID‑19 pandemic, helped meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments for selected personal protective equipment and medical devices, and whether Public Services and Procurement Canada provided adequate procurement support:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Public Health Agency of Canada manages the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile to meet the needs of the federal, provincial, and territorial governments before and during the pandemic. |

|

|

The Public Health Agency of Canada assesses the personal protective equipment and medical device needs of the federal, provincial, and territorial governments. The Public Health Agency of Canada, in coordination with other federal departments and agencies, allocates equipment on the basis of needs. |

|

|

Health Canada authorizes new equipment and suppliers. The Public Health Agency of Canada conducts quality assurance of equipment procured by Public Services and Procurement Canada. |

|

|

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s COVID‑19 procurement strategy for equipment focuses on needs, and is implemented with due diligence. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2020 to 31 August 2020. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period. This included our examination of the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 24 March 2021, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Jean Goulet

Director: Milan Duvnjak

Meaghan Burnham

Paul Csagoly

Somen Dutta

Sébastien Labonté

Amanda Lapierre

Susan Ly

Yusuf Saibu

Ludovic Silvestre

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Assessing needs and managing the federal stockpile

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

10.38 The Public Health Agency of Canada should develop and implement a comprehensive National Emergency Strategic Stockpile management plan with clear timelines that responds to relevant federal stockpile recommendations made in previous internal audits and lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic. (10.34 to 10.37) |

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s response. Agreed. The Public Health Agency of Canada states that the experience of COVID‑19 has provided a lived experience of a global pandemic, the nature of which Canada has not seen in over 100 years. Recognizing that existing policies, practices, and resources were leveraged to guide the current response, lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic will inform how the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile is managed going forward. The agency is currently working on a comprehensive management plan with associated performance measures and targets for the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile to support responses to future public health emergencies. This plan will focus on key areas such as optimizing life-cycle material management, enhancing infrastructure and systems, and working closely with provinces and territories and other key partners to better define needs and roles and responsibilities. The agency will continue to identify and implement incremental improvements during its ongoing efforts to respond to COVID‑19. The agency is expecting to complete the comprehensive National Emergency Strategic Stockpile management plan with clear timelines for implementation within 1 year of the end of the pandemic. |

|

10.51 The Public Health Agency of Canada should enforce, as appropriate, the terms and conditions in its contracts with third-party warehousing and logistics service providers—including the long-term contract signed in September 2020—for the provision of timely, accurate, and complete data to help control inventory of personal protective equipment and medical devices. (10.47 to 10.50) |

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s response. Agreed. Since the long-term contracts were established, the Public Health Agency of Canada continues to work closely with its third-party warehousing and logistics service providers for the provision of timely, accurate, and complete data to help control personal protective equipment and medical devices and, if required, will take appropriate actions to enforce the terms and conditions in these contracts. |

Procuring equipment and ensuring quality

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

10.82 Health Canada should determine whether respirators are appropriately classified given that Class I medical devices are not subject to a Health Canada review for safety and effectiveness. (10.78 to 10.81) |

Health Canada’s response. Agreed. While Health Canada currently regulates medical devices in accordance with a risk-based classification system, consideration could be given to providing greater pre-market oversight over some lower-risk devices. Health Canada acknowledges the challenges associated with ensuring that the safety, effectiveness, and quality requirements for respirators are met in situations such as the COVID‑19 pandemic. Under the existing Medical Devices Regulations, a pre-market evaluation is not an option for Class I medical devices. However, under the interim order (IO) pathway, Health Canada was afforded regulatory flexibilities allowing for pre-market review of respirators. Post-market surveillance activities, including inspections, and scientific evaluations under the IO, increased Health Canada’s awareness of low-quality respirators that have the potential to enter the Canadian market. Health Canada will specifically review the classification of lower-risk devices, including respirators, in the context of the development of Agile Regulations for Medical Devices. While in its infancy, this initiative is underway and will provide an opportunity to determine whether respirators are appropriately classified. Health Canada is committed to exploring options to evaluate the appropriate level of pre-market oversight of these devices. An issue analysis will be conducted within 1 year of the end of the pandemic. |

|

10.102 Public Services and Procurement Canada, while addressing urgent needs and accepting procurement risks, should conduct checks of the financial strength of suppliers before awarding contracts that involve advance payment. (10.97 to 10.101) |

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. The audit acknowledges that Public Services and Procurement Canada mobilized its workforce and adapted quickly to deliver on urgent procurement requirements for Canadians. Procuring the goods and services required to combat the pandemic, particularly in the first 100 days (the focus of this audit), was an around-the-clock effort, undertaken in an unprecedented environment of extremely tight global supply chains. This presented challenges ranging from being able to action contracts outside of regular business hours, address logistics, and undertake new critical activities such as the Essential Services Contingency Reserve. While the department established processes at the outset of the pandemic aimed at ensuring oversight and due diligence processes, we recognize that procurement processes can always be improved, and in the context of advance payments, this includes undertaking financial checks. Over the course of the last year, the department has continuously evolved its approaches. Going forward, the department will further update its processes related to emergency procurements to address lessons learned through the course of this audit and other exercises, while continuing to prioritize the health and safety of Canadians. |