2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 11—Health Resources for Indigenous Communities—Indigenous Services Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Personal protective equipment

- Nurses and paramedics

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits

- 11.1—Indigenous Services Canada received 2% of the personal protective equipment (PPE) from the Public Health Agency of Canada

- 11.2—From March to December 2020, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) provided personal protective equipment to Indigenous communities and organizations when other sources were not available

- 11.3—Indigenous Services Canada responded to 1,622 requests for personal protective equipment from March 2020 to January 2021

- 11.4—Total amount of personal protective equipment that Indigenous Services Canada provided to Indigenous communities and organizations from March to December 2020

- 11.5—From March to November 2020, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) provided personal protective equipment (PPE) to communities within 10.5 days of receiving the request

- 11.6—Indigenous Services Canada was unable to meet more than half of the requests for contract nurses and paramedics to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic

Introduction

Background

11.1 Various social, environmental, and economic factors in IndigenousDefinition 1 communities increase the risk of outbreaks of infectious diseases like the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 2. These factors include

- high rates of chronic disease and pre-existing health conditions

- inadequate housing and overcrowding

- limited access to health care services

- limited access to safe drinking water

11.2 In Canada, the first case of COVID‑19 was reported in January 2020. The virus then spread throughout Canada, including in Indigenous communities. As of 13 April 2021, Indigenous Services Canada was aware of 25,789 confirmed positive cases of COVID‑19 in First Nations people living on reserve. Of these, 1,153 people were hospitalized and 299 people died. Compared with the general Canadian population, First Nations people living in on-reserve communities were less likely to be hospitalized (4.5% compared with 7.5%) or die (1.2% compared with 2.2%) from COVID‑19. Other Indigenous groups, including First Nations people living off reserve, Inuit, and Métis people, have also been affected by the COVID‑19 pandemic.

11.3 Provinces and territories. During a communicable disease emergency, the provinces and territories provide personal protective equipment (PPE)Definition 3 to health care workers and others supporting the delivery of health services within their borders according to the allocation guidelines in their jurisdictions.

11.4 Indigenous Services Canada. The department supports the delivery of health care services, by doing the following:

- The department delivers direct health care services in 51 remote or isolated First Nations communitiesDefinition 4. It employs primary health care workers to provide health care services in these communities.

- The department provides funding to First Nations communities and First Nations health authorities for health care services. These communities and health authorities directly employ health care workers to provide health care services.

11.5 The department also maintains a stockpile of PPE and hand sanitizer for use during public health emergencies. According to its 2014 policy, the department will provide PPE to health care workers and those who support the delivery of health care services in all First Nations communities in the event of a public health emergency.

11.6 PPE is critical to protecting Canadians’ health, especially during infectious disease outbreaks, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic. Front-line health care workers rely on PPE to protect themselves and others from being infected by communicable diseases. In March 2020, the World Health Organization recognized that there was a worldwide shortage of PPE, leaving many health care workers ill-equipped to deal with the COVID‑19 pandemic. These shortages also affected health care workers throughout Canada.

11.7 In the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities where the department provides primary health care services, nurses work out of nursing stations or health centres and are often the only health care providers working on site. They work in pairs or small groups, often with little or no on-site support from other health care professionals. They respond to urgent needs and medical emergencies, such as accidents, heart attacks, strokes, and childbirth. Some health care services are not offered in all communities. In these situations, patients receive treatment outside of their communities.

11.8 Nursing shortages are prevalent in many of these communities. It can be difficult to recruit and retain nurses for a number of reasons, including

- the national shortage of nurses

- the challenging nature of the work

- the diverse skill set required to work in these remote or isolated communities

- inadequate housing

11.9 In September 2015, Canada committed to achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The topic of this audit aligns with the goal of health and well-being (Goal 3), which is to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.” In particular, this goal has a target for achieving “universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”

Focus of the audit

11.10 This audit focused on whether Indigenous Services Canada provided sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), nurses, and paramedics to Indigenous communities and organizations in a coordinated and timely manner in order to protect Indigenous peoples against COVID‑19.

11.11 We examined whether Indigenous Services Canada maintained a sufficient stockpile of PPE. We also examined whether it coordinated with other federal organizations, provincial and territorial governments, and Indigenous governments and organizations to provide PPE, nurses, and paramedics to Indigenous communities and organizations.

11.12 This audit is important because without access to PPE and medical support during a pandemic, Indigenous communities, which are often already at risk of higher rates of illness, may be more susceptible to COVID‑19. The increased risk is related to a number of factors, such as high rates of chronic disease and pre-existing health conditions, inadequate housing and overcrowding, limited access to health care services, and limited access to safe drinking water.

11.13 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

11.14 In May 2021, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada also published the 2021 Reports of the Auditor of General of Canada, Report 10—Securing Personal Protective Equipment and Medical Devices. It focused on whether the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada, before and during the COVID‑19 pandemic, helped to meet the needs of provincial and territorial governments for selected PPE and medical devices. The audit also focused on whether Public Services and Procurement Canada provided adequate procurement support to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

11.15 Overall, although we found weaknesses in Indigenous Services Canada’s management of its personal protective equipment (PPE) stockpile, the department adapted quickly to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic. The department expanded access to its PPE stockpile to health care workers in Indigenous communities and organizations when provinces and territories were unable to provide PPE. It also expanded access to its stockpile to additional individuals supporting the delivery of health services, such as community-based water monitors and police officers, as well as people in communities who were sick with COVID‑19 or taking care of a sick family member. The department’s support helped Indigenous communities and organizations respond to the pandemic.

11.16 Indigenous Services Canada streamlined its processes for hiring nurses in remote or isolated First Nations communities and also made its contract nurses and paramedics available to all Indigenous communities to respond to the additional health care needs caused by COVID‑19. Despite this, the department was unable to meet more than half of the requests for extra contract nurses and paramedics needed to respond to COVID‑19.

11.17 Responding to the COVID‑19 pandemic and future public health emergencies requires continued partnership between the department and Indigenous communities and organizations.

Personal protective equipment

Indigenous Services Canada adapted its response for personal protective equipment needs during the pandemic

11.18 Before the COVID‑19 pandemic, Indigenous Services Canada procured its own supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) for its stockpile to support Indigenous communities to manage communicable disease emergencies. In 2014, the department developed a procurement approach that outlined how much PPE it needed in its stockpile to be ready for a communicable disease outbreak. However, we found that the department did not follow this approach and, therefore, did not have sufficient amounts of some PPE items at the beginning of the pandemic.

11.19 Starting in April 2020, the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy required that the Public Health Agency of Canada provide Indigenous Services Canada with 2% of all bulk purchases of PPE. We found that with the help of this increased supply, the department expanded access to its PPE stockpile and provided PPE to Indigenous communities and organizations when provinces and territories were unable to provide PPE. The department responded to 1,622 requests for PPE in a timely manner, within 10 days on average from the date the department received the request to the date the community received the shipment.

11.20 We found weaknesses in the way that Indigenous Services Canada managed its stockpile of PPE. The department did not have complete and accurate data on the stockpile’s contents. We also found that although the department set a target of having a 6-month supply of PPE in stock, throughout the pandemic, it had more than its 6-month target for some items.

11.21 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Insufficient amounts of some PPE items before the COVID‑19 pandemic

- PPE provided when needed during the COVID‑19 pandemic

- Collaboration between department and partners

- Improved system for processing PPE requests

- Weaknesses in management of PPE stockpile

11.22 This finding matters because if the department does not provide the PPE needed by health care workers in Indigenous communities and organizations in a timely manner, health care workers may not be adequately protected against COVID‑19. Without access to PPE, Indigenous peoples will be more susceptible to the spread of COVID‑19.

11.23 In 2003, following the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Indigenous Services Canada (which was then part of Health Canada) began procuring PPE to build its own stockpile.

11.24 Before the COVID‑19 pandemic, the department’s PPE stockpile was to be used by health care workers and those supporting the delivery of health care services in First Nations communities during public health emergencies, including those health care workers it employs in the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities. Under the Canada Labour Code and the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations, the department must ensure that the health care workers it employs have access to PPE when necessary.

11.25 In April 2020, the federal, provincial, and territorial governments launched the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy. The strategy states that the Public Health Agency of Canada is responsible for allocating PPE to the provinces and territories and to federal departments with responsibility for specific populations, including Indigenous peoples. According to the strategy, the Public Health Agency of Canada would provide 2% of bulk purchases of PPE to Indigenous Services Canada during the pandemic (Exhibit 11.1).

Exhibit 11.1—Indigenous Services Canada received 2% of the personal protective equipment (PPE) from the Public Health Agency of Canada

Source: Based on documents provided by Indigenous Services Canada

Exhibit 11.1—text version

This flow chart shows how the Public Health Agency of Canada allocates personal protective equipment.

The provinces and territories get 80%.

The National Emergency Strategic Stockpile gets 18%.

Indigenous Services Canada gets 2%.

11.26 Indigenous Services Canada used PPE calculators to determine the amount of PPE to provide to communities and organizations. The calculators used assumptions about Indigenous communities, the COVID‑19 virus and its transmission, and how health care services are performed. There were different calculators to determine the amount of PPE to provide to different workers, including nurses, environmental public health officers, oral health service providers, and police officers.

11.27 When determining the amount of PPE to provide to health care workers, the department committed to following federal, provincial, and territorial health guidelines based on where the health care service was being provided.

11.28 Indigenous communities and organizations submitted requests for PPE to Indigenous Services Canada. Department staff then assessed each request using the appropriate calculator to determine the quantity of PPE to send. The department’s internal service standards for processing PPE requests stated that requests should be approved and sent to the warehouse for shipping within 2 business days.

11.29 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 11.46.

Insufficient amounts of some PPE items before the COVID‑19 pandemic

11.30 We found that the department did not procure PPE according to its 2014 procurement approach. This approach outlined how much stock it needed to purchase over a 4-year period to be ready for a moderate to severe communicable disease emergency. We found that at the beginning of the COVID‑19 pandemic, in March 2020, the department did not have the stock it committed to in its approach for some items, such as gloves, masks, N95 respirators, and hand sanitizer. However, it had a sufficient supply of face shields and gowns.

11.31 We noted that while the department did not have sufficient amounts of some items in its own stockpile, it was able to rely on the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile for additional PPE during the pandemic to respond to requests from Indigenous communities and organizations.

PPE provided when needed during the COVID‑19 pandemic

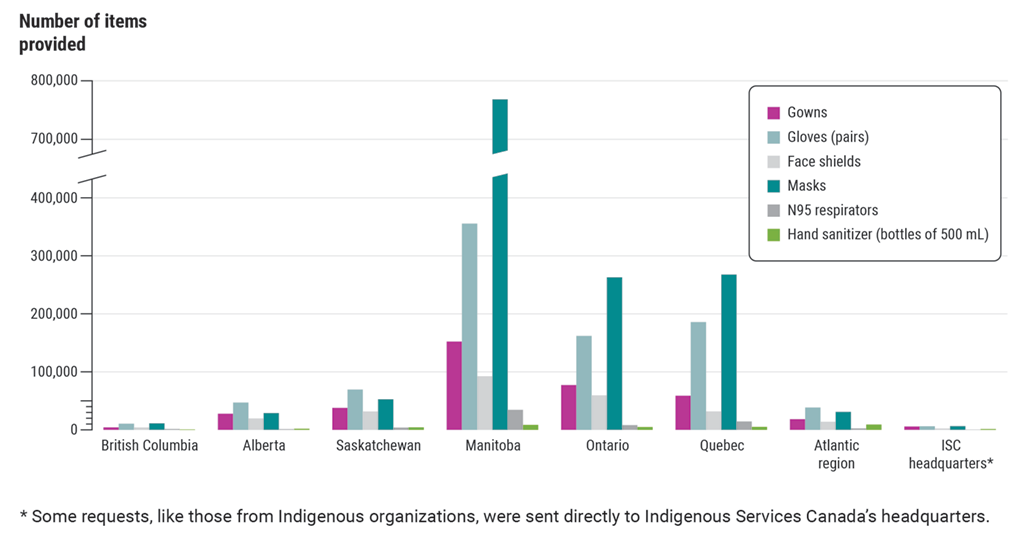

11.32 Expanded access to PPE. Starting in April 2020, the department relied on the PPE provided under the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy for its supply of PPE during the pandemic. We found that the department provided PPE to Indigenous communities and organizations when provinces and territories were unable to provide it (Exhibit 11.2).

Exhibit 11.2—From March to December 2020, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) provided personal protective equipment to Indigenous communities and organizations when other sources were not available

Notes:

1. The variations in the amount of personal protective equipment that Indigenous Services Canada provided can be partly explained by rates of COVID‑19 cases in different parts of the country, and because other sources of personal protective equipment were unavailable.

2. An N95 respirator is a personal protective device that fits tightly around the nose and mouth and is used to reduce the risk of inhaling hazardous airborne particles and aerosols, including infectious agents. Masks refer to surgical or procedure masks. Unlike N95 respirators, masks are looser in fit. As a result, they do not provide the same level of protection.

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

Exhibit 11.2—text version

This bar chart shows the number of items of personal protective equipment (PPE) that Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) provided from March to December 2020 to Indigenous communities and organizations across Canada when other sources were not available.

Overall, from March to December 2020, Indigenous Services Canada provided Indigenous communities and organizations in Manitoba with the highest number of PPE items, including the highest number of gowns, pairs of gloves, face shields, masks, and N95 respirators.

Overall, from March to December 2020, Indigenous Services Canada provided British Columbia with the lowest number of gowns and 500-millilitre bottles of hand sanitizer.

The department provided Indigenous communities and organizations in British Columbia with 4,250 gowns, 10,550 pairs of gloves, 4,100 face shields, 11,200 masks, 1,560 N95 respirators, and 760 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

The department provided Indigenous communities and organizations in Alberta with 27,750 gowns, 47,000 pairs of gloves, 19,659 face shields, 28,900 masks, 1,180 N95 respirators, and 1,864 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

The department provided Indigenous communities and organizations in Saskatchewan with 37,874 gowns, 69,393 pairs of gloves, 31,676 face shields, 52,750 masks, 3,900 N95 respirators, and 4,294 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

The department provided Indigenous communities and organizations in Manitoba with 152,176 gowns, 355,494 pairs of gloves, 92,412 face shields, 767,252 masks, 34,500 N95 respirators, and 8,568 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

The department provided Indigenous communities and organizations in Ontario with 72,208 gowns, 161,871 pairs of gloves, 59,495 face shields, 262,923 masks, 8,160 N95 respirators, and 4,870 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

The department provided Indigenous communities and organizations in Quebec with 58,810 gowns, 185,736 pairs of gloves, 31,788 face shields, 267,650 masks, 14,480 N95 respirators, and 5,113 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

The department provided Indigenous communities and organizations in the Atlantic region with 18,426 gowns, 38,434 pairs of gloves, 13,921 face shields, 30,940 masks, 2,528 N95 respirators, and 9,110 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

Some requests, like those from Indigenous organizations, were sent directly to Indigenous Services Canada’s headquarters. These requests were for 5,730 gowns, 6,200 pairs of gloves, 2,233 face shields, 6,400 masks, 500 N95 respirators, and 1,380 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer.

11.33 In addition, at the beginning of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the department expanded access to the stockpile to include not only health care workers but also additional individuals supporting the delivery of health services, such as community-based water monitors and police officers, as well as people in communities who were sick with COVID‑19 or taking care of a sick family member.

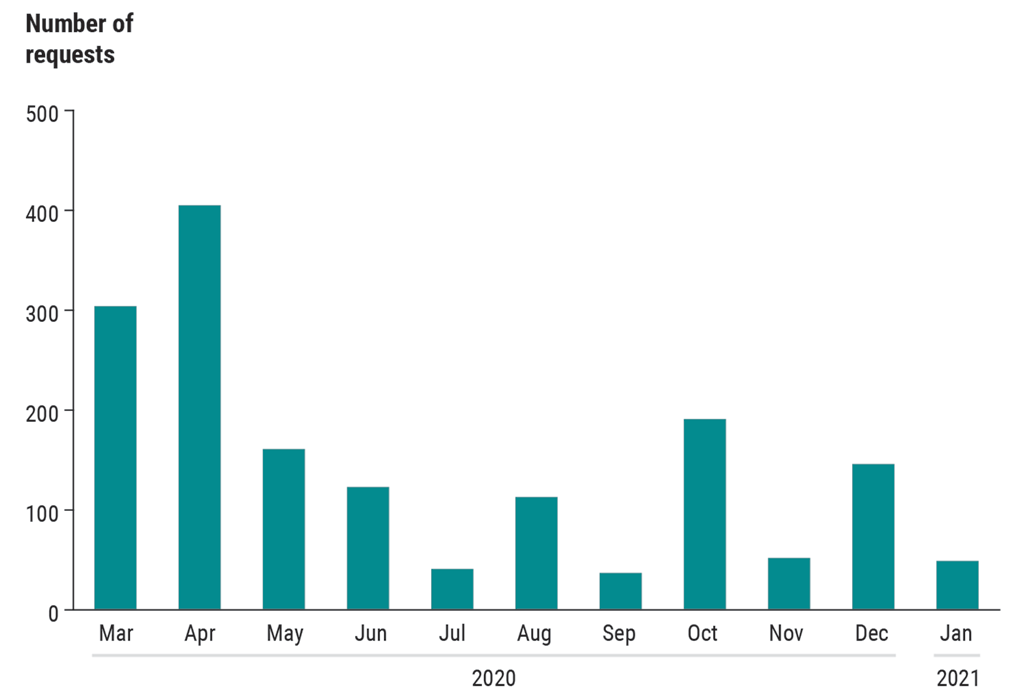

11.34 From March 2020 to January 2021, Indigenous Services Canada responded to 1,622 requests for PPE (Exhibit 11.3). As of December 2020, it had provided 3,045,697 items of PPE to 454 communities and organizations (Exhibit 11.4).

Exhibit 11.3—Indigenous Services Canada responded to 1,622 requests for personal protective equipment from March 2020 to January 2021

Note: Requests were higher at the beginning of the pandemic and as cases started to rise in First Nations communities in October 2020. Starting in December 2020, Indigenous Services Canada began sending a 3‑month supply of personal protective equipment to account for difficulties in reaching some communities during the winter.

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

Exhibit 11.3—text version

This bar chart shows the number of requests for personal protective equipment that Indigenous Services Canada responded to by month from March 2020 to January 2021. Overall, the department responded to 1,622 requests. The month with the highest number of requests during this period was April 2020, and the month with the lowest number of requests during this period was September 2020.

In March 2020, the department responded to 304 requests.

In April 2020, the department responded to 405 requests.

In May 2020, the department responded to 161 requests.

In June 2020, the department responded to 123 requests.

In July 2020, the department responded to 41 requests.

In August 2020, the department responded to 113 requests.

In September 2020, the department responded to 37 requests.

In October 2020, the department responded to 191 requests.

In November 2020, the department responded to 52 requests.

In December 2020, the department responded to 146 requests.

In January 2021, the department responded to 49 requests.

Exhibit 11.4—Total amount of personal protective equipment that Indigenous Services Canada provided to Indigenous communities and organizations from March to December 2020

Note: An N95 respirator is a personal protective device that fits tightly around the nose and mouth, and is used to reduce the risk of inhaling hazardous airborne particles and aerosols, including infectious agents. Masks refer to surgical or procedure masks. Unlike N95 respirators, masks are looser in fit. As a result, they do not provide the same level of protection.

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

Exhibit 11.4—text version

This pie chart shows the number of each type of personal protective equipment that Indigenous Services Canada provided to Indigenous communities and organizations between March and December 2020.

In descending order, the department provided

- 1,429,015 masks

- 875,928 pairs of gloves

- 382,324 gowns

- 255,311 face shields

- 66,848 N95 respirators

- 36,271 bottles of 500 millilitres of hand sanitizer

11.35 Timely provision of PPE. We found that the department provided PPE to Indigenous communities and organizations in a timely manner. This is significant given the challenge of shipping items to communities that are often remote or isolated. Other factors that can contribute to shipping delays include inclement weather, limited flight schedules (sometimes only once a week), and complex shipping routes.

11.36 From March 2020 to January 2021, the department responded to 1,622 requests for PPE in a timely manner—within an average of 10 calendar days, communities received their shipments of PPE. For example, on 28 October 2020, a community requested PPE from the department. Six calendar days later, on 3 November 2020, it received its shipment of 200 gowns, 300 pairs of gloves, 153 face shields, and 800 masks.

11.37 We also found that most of the time, the department met its 2-business-day service standard for approving and sending requests to the warehouse for shipping. From March 2020 to the end of November 2020, 82% of requests were processed within an average of just over one and a half business days (Exhibit 11.5). The longest processing time was 12 business days.

Exhibit 11.5—From March to November 2020, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) provided personal protective equipment (PPE) to communities within 10.5 days of receiving the request

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

Exhibit 11.5—text version

This flow chart shows the process for shipments of personal protective equipment (PPE) and the average time frames between different steps.

When a community was unable to obtain PPE from its usual supplier or the provincial or territorial stockpile, it sent a PPE request to the Indigenous Services Canada regional office.

The regional office added the community’s information to the form and sent it to Indigenous Services Canada’s headquarters.

Indigenous Services Canada’s headquarters processed the request and sent the shipment information to the warehouse in an average of 1.6 business days.

The warehouse prepared the package of PPE and sent it to the community.

The community received the package.

On average, the community received its shipment of PPE 10.5 calendar days after the regional office received the community’s request.

Collaboration between department and partners

11.38 We found that the department met with Indigenous communities and organizations throughout the pandemic to discuss how it could support them with the PPE that they needed. The department told us that they also had ongoing communications with federal organizations and the provinces and territories.

Improved system for processing PPE requests

11.39 We found that from March to August 2020, the department’s process for managing PPE involved multiple steps that relied on manual inputs of requests for PPE from Indigenous communities and organizations. According to the department, this led to errors in capturing information on requests. The department did not always have complete and accurate information on the amount of PPE that was being sent to communities and organizations from the stockpile.

11.40 In September 2020, the department introduced a new system to electronically process PPE requests. We found this system reduced the possibility of human error and led to more complete and accurate information on requests for PPE.

Weaknesses in management of PPE stockpile

11.41 We found that during the pandemic, the department did not have complete and accurate data on the contents of its PPE stockpile. The department’s documentation of the stockpile contents was inconsistent and contained errors. Some shipments of PPE that the department received under the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy were, at times, accounted for in the inventory several weeks to over a month after the shipment was received. We also found that in other cases, there were discrepancies in the amount of items of PPE logged in the inventory. For example, on 17 August 2020, a shipment was recorded in the department’s inventory tracking spreadsheet as 90,610 items of PPE and was later revised on 30 November 2020 to 686,182 items, a difference of 595,572 items. As a result, the department did not always have an accurate picture of what was in its inventory.

11.42 We also found that from April 2020 to June 2020, the department submitted 4 requests for assistance to the Public Health Agency of Canada for PPE when it was low on stock. These requests were in addition to the department’s 2% allocation under the Allocation of Scarce Resources—COVID‑19 Interim Response Strategy. It made no additional requests for PPE after this period.

11.43 The lack of complete and accurate data on the contents of the PPE stockpile made it difficult for the department to monitor its inventory levels and determine its needs. During the pandemic, the department’s target was to have at least 6 months’ worth of PPE in its stockpile at any time. It estimated the number of months of inventory left in the stockpile by measuring the rate at which PPE was distributed and dividing that by the inventory in its stockpile.

11.44 We also found that throughout the pandemic, the department had more than its target for some items. On 1 occasion, the department took action to temporarily stop shipments of hand sanitizer because of safety concerns related to its storage. However, the department did not take action to stop shipments of other items when it had surpassed its 6-month target.

11.45 The department told us that it continued to accept shipments of PPE because of the changing nature of the virus. For example, variants of the virus introduced into Canada could result in increased demand for PPE in Indigenous communities.

11.46 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada should review the management of its personal protective equipment stockpile to ensure that it has accurate records and the right amount of stock to respond to the current pandemic and future public health emergencies faced by Indigenous communities and organizations.

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada reviewed its initial inventory of personal protective equipment (PPE) from before the COVID‑19 pandemic and compared it with the average burn rate for PPE for the first year of the pandemic. The department found that, overall, it was in good standing to meet the needs of First Nations communities in relation to the intended use of the PPE stockpile for department-employed health care workers, under its legal obligation. Additionally, 2% of each PPE shipment procured by Public Services and Procurement Canada was allocated to Indigenous Services Canada through the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Emergency Strategic Stockpile, under the federal-provincial-territorial–approved policy of the allocation of scarce resources during the pandemic.

To ensure that Indigenous Services Canada has accurate records and the optimum amount of stock to respond to the current and future public health emergencies, the department has completed the first phase of an automated inventory management tool. The first phase is completed to track outbound inventory. Work for the next phase to track inbound inventory has begun. The department is reviewing its cyclical approach for purchasing and disposing of PPE to allow for an optimum amount of stock to be maintained. Finally, the department is finalizing inventory management requirements for warehousing services that meet the needs for tracking the department’s inventory.

The department will continue to identify and maintain optimum amounts of PPE in its stockpile for the needs of First Nations people living on reserve to respond to public health emergencies. It will continue to work with provincial, territorial, and federal partners in identifying the optimum amounts of PPE to protect Indigenous peoples.

Nurses and paramedics

Despite expanding access to contract nurses and paramedics, over half of requests for additional health care staff to respond to COVID‑19 needs were not met

11.47 We found that Indigenous Services Canada streamlined its staffing process to more quickly hire nurses to work in the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities where it is responsible for delivering primary health care services.

11.48 To address extra needs for health care resources to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic in Indigenous communities, the department made its nursing contracts with staffing agencies available to all Indigenous communities. It also created new national contracts for nurses and paramedics to address the need for additional resources to respond to COVID‑19 in all Indigenous communities.

11.49 We found that, despite expanding access to its contracts for nurses and paramedics to all Indigenous communities, the department could not over half of the time provide the additional contract nurses and paramedics that were needed to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic in these communities. The pandemic exacerbated challenges that existed prior to the pandemic in meeting nursing needs in the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities. Several factors contributed to nursing shortages in many of these communities, including the national shortage of nurses, the challenging nature of the work, the diverse skill set required to work in remote or isolated communities, and inadequate housing.

11.50 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Streamlined hiring, expanded access to existing contracts for nurses, and new contracts for nurses and paramedics to respond to COVID‑19

- Inability to meet all requests for contract nurses and paramedics to respond to COVID‑19

11.51 This finding matters because if the department cannot provide the nurses and paramedics that Indigenous communities need, these communities may be at risk of not receiving necessary health care services, especially during a health emergency such as the COVID‑19 pandemic.

11.52 The department is responsible for supporting the delivery of primary health care services to First Nations communities. This includes employing nurses to work in 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities. The department recruits and hires nurses, and these nurses are federal employees. It also has contracts with staffing agencies to help fill gaps in nursing needs in these communities.

11.53 Given the challenging nature of the work, the diverse skill set required to work in these remote or isolated communities, and the lack of adequate housing, it is difficult for the department to recruit and retain nurses to work in these communities. As a result, many of these nursing stations and health centres are understaffed.

11.54 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 11.61.

Streamlined hiring, expanded access to existing contracts for nurses, and new contracts for nurses and paramedics to respond to COVID‑19

11.55 During the pandemic, the department streamlined its staffing process so that it could more quickly hire additional nurses to work in the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities. According to the department, in the 12 months before the pandemic, it hired 77 nurses to work in the 51 communities, whereas from March 2020 to March 2021, it hired 147 nurses.

11.56 Before the COVID‑19 pandemic, the department used contracts to fill gaps in nursing needs in the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities. During the pandemic, the department also addressed the need for extra resources through its contracts with staffing agencies.

11.57 We found that the department expanded access to its existing contract nurses by making nurses available to all Indigenous communities. It also created new contracts for nurses and paramedics to respond to COVID‑19 in any Indigenous community.

11.58 To avoid interruptions to essential health services caused by the cancellation of flights to the 51 communities during the pandemic, the department told us that it chartered dedicated air services to transport almost 5,400 inbound and outbound passengers from April 2020 to March 2021.

Inability to meet all requests for contract nurses and paramedics to respond to COVID‑19

11.59 We found that, despite expanding access to its existing contracts for nurses and creating new contracts for nurses and paramedics, the department was unable to meet over half of the requests for extra contract nurses and paramedics needed to respond to COVID‑19. From March 2020 to March 2021, the department received 963 requests for extra contract nurses and paramedics to respond to COVID‑19. It was unable to meet 505 (52%) of these requests (Exhibit 11.6). This increased the risk that some communities could not access the health services they needed during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

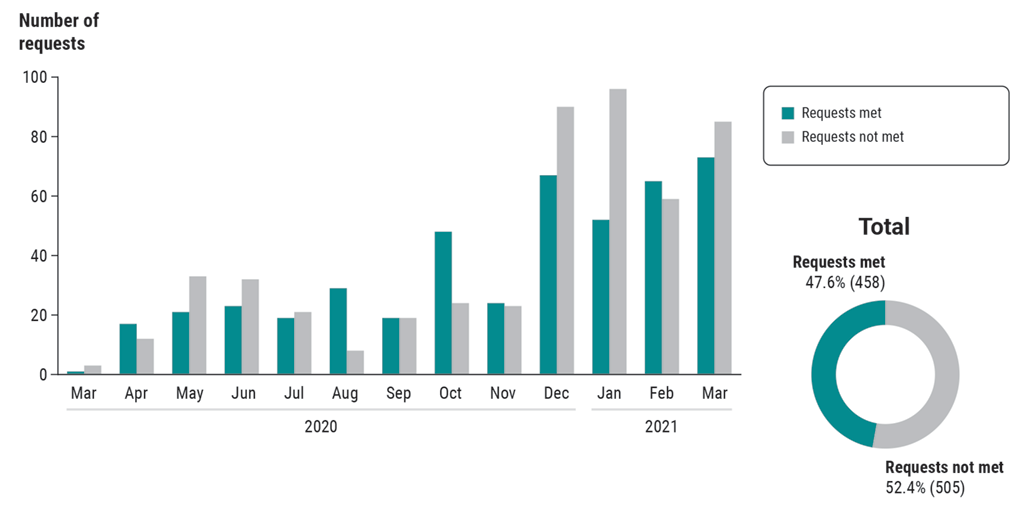

Exhibit 11.6—Indigenous Services Canada was unable to meet more than half of the requests for contract nurses and paramedics to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic

Exhibit 11.6—text version

The bar chart shows the number of requests for contract nurses and paramedics that Indigenous Services Canada met and did not meet from March 2020 to March 2021. The number of requests significantly increased in the last four months of the period.

In March 2020, the department met 1 request and did not meet 3 requests.

In April 2020, the department met 17 requests and did not meet 12 requests.

In May 2020, the department met 21 requests and did not meet 33 requests.

In June 2020, the department met 23 requests and did not meet 32 requests.

In July 2020, the department met 19 requests and did not meet 21 requests.

In August 2020, the department met 29 requests and did not meet 8 requests.

In September 2020, the department met 19 requests and did not meet 19 requests.

In October 2020, the department met 48 requests and did not meet 24 requests.

In November 2020, the department met 24 requests and did not meet 23 requests.

In December 2020, the department met 67 requests and did not meet 90 requests.

In January 2021, the department met 52 requests and did not meet 96 requests.

In February 2021, the department met 65 requests and did not meet 59 requests.

In March 2021, the department met 73 requests and did not meet 85 requests.

The pie chart shows that overall, Indigenous Services Canada met 47.6% of requests (a total of 458) and did not meet 52.4% (a total of 505).

11.60 Exhibit 11.6 illustrates that as the pandemic progressed, both the number of requests for extra contract nurses and paramedics and the department’s capacity to provide contract nurses and paramedics increased. However, the department was still unable to respond to all requests.

11.61 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada should work with the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities to consider other approaches to address the ongoing shortage of nurses in these communities and to review the nursing and paramedic support provided to all Indigenous communities to identify best practices.

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada agrees with collaborating with the 51 First Nations communities it directly serves in developing approaches to addressing staff shortages, including the health-human-resource complement and best-practice models for the community. The department will work through its Nursing Leadership Council to identify new approaches and best practices in

- engaging First Nations communities in staffing processes

- expanding the skill mix of health professionals, such as paramedics and licensed practical nurses

Conclusion

11.62 We found weaknesses in Indigenous Services Canada’s management of its personal protective equipment (PPE) stockpile before and during the pandemic. However, we concluded that the department provided PPE to Indigenous communities and organizations in a timely manner. In addition, the department expanded access to its PPE stockpile to include Indigenous organizations, more Indigenous communities, and additional individuals supporting the delivery of health care services.

11.63 We also concluded that Indigenous Services Canada streamlined its processes for hiring nurses, expanded access to its contract nurses to all Indigenous communities, and created new contracts for nurses and paramedics. Despite this, the department was unable to meet more than half of the requests for extra contract nurses and paramedics needed to respond to COVID‑19.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) and health care workers to Indigenous communities and organizations during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the PPE and health care workers provided by Indigenous Services Canada to Indigenous communities and organizations complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Indigenous Services Canada provided sufficient PPE and health human resources to Indigenous communities and organizations in a coordinated and timely manner in order to protect Indigenous peoples against COVID‑19.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on whether Indigenous Services Canada, during the COVID‑19 pandemic, provided Indigenous communities and organizations with sufficient and timely PPE from the department’s stockpile, and with health care workers to manage COVID‑19. The audit also examined whether the department maintained a sufficient stockpile of PPE. In addition, we examined how the department coordinated its efforts to provide PPE and health care workers with other federal organizations, provincial and territorial governments, and Indigenous governments.

We did not examine the performance of Indigenous communities or organizations, provincial and territorial governments, or other federal organizations. We also did not examine the funding that Indigenous Services Canada provided to Indigenous communities to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic for, among other things, purchasing PPE, hiring health care workers, providing mental health services, and establishing community perimeter security. Because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, we did not visit Indigenous communities or organizations during our audit.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether Indigenous Services Canada provided sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) and health human resources to Indigenous communities and organizations in a coordinated and timely manner in order to protect Indigenous peoples against COVID‑19:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Indigenous Services Canada has a framework for prioritizing the allocation of PPE and health human resources among Indigenous communities and organizations. |

|

|

Indigenous Services Canada provides sufficient and timely PPE and health human resources to Indigenous communities and organizations. |

|

|

Indigenous Services Canada maintains a sufficient stockpile of PPE. |

|

|

Indigenous Services Canada coordinates with Indigenous governments, other federal organizations, and provincial and territorial governments to provide PPE and health human resources to Indigenous communities and organizations. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2020 to 31 March 2021. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 23 April 2021, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Glenn Wheeler

Director: Doreen Deveen

Valérie La France-Moreau

Maxine Leduc

Zackary Partington

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Personal protective equipment

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

11.46 Indigenous Services Canada should review the management of its personal protective equipment stockpile to ensure that it has accurate records and the right amount of stock to respond to the current pandemic and future public health emergencies faced by Indigenous communities and organizations. (11.41 to 11.45) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada reviewed its initial inventory of personal protective equipment (PPE) from before the COVID‑19 pandemic and compared it with the average burn rate for PPE for the first year of the pandemic. The department found that, overall, it was in good standing to meet the needs of First Nations communities in relation to the intended use of the PPE stockpile for department-employed health care workers, under its legal obligation. Additionally, 2% of each PPE shipment procured by Public Services and Procurement Canada was allocated to Indigenous Services Canada through the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Emergency Strategic Stockpile, under the federal-provincial-territorial–approved policy of the allocation of scarce resources during the pandemic. To ensure that Indigenous Services Canada has accurate records and the optimum amount of stock to respond to the current and future public health emergencies, the department has completed the first phase of an automated inventory management tool. The first phase is completed to track outbound inventory. Work for the next phase to track inbound inventory has begun. The department is reviewing its cyclical approach for purchasing and disposing of PPE to allow for an optimum amount of stock to be maintained. Finally, the department is finalizing inventory management requirements for warehousing services that meet the needs for tracking the department’s inventory. The department will continue to identify and maintain optimum amounts of PPE in its stockpile for the needs of First Nations people living on reserve to respond to public health emergencies. It will continue to work with provincial, territorial, and federal partners in identifying the optimum amounts of PPE to protect Indigenous peoples. |

Nurses and paramedics

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

11.61 Indigenous Services Canada should work with the 51 remote or isolated First Nations communities to consider other approaches to address the ongoing shortage of nurses in these communities and to review the nursing and paramedic support provided to all Indigenous communities to identify best practices. (11.59 to 11.60) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada agrees with collaborating with the 51 First Nations communities it directly serves in developing approaches to addressing staff shortages, including the health-human-resource complement and best-practice models for the community. The department will work through its Nursing Leadership Council to identify new approaches and best practices in

|