2023 Reports 5 to 9 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 5—Inclusion in the Workplace for Racialized Employees

At a Glance

Many initiatives have been undertaken in the public service over decades to address known barriers and inequities in the workplace. None of these resulted in the full removal of barriers and in the achievement of equity. In the past 5 years, several have taken place, including the January 2021 Call to Action on Anti‑Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service, which called upon public service leaders to combat all forms of racism, discrimination, and other barriers to inclusion in the workplace. The accountability rests with senior leaders to guide federal organizations to identify and address the barriers and conditions of disadvantage that racialized employees and other designated groups report experiencing in the public service.

To assess progress made to foster an inclusive organizational culture in the federal public service, we selected 6 organizations responsible in whole or in part for providing safety, the administration of justice, or policing services in Canada. Together, they employ about 21% of workers in the federal core public administration.

While we found that Canada Border Services Agency, Correctional Service Canada, Justice Canada, Public Prosecution Service of Canada, Public Safety Canada, and Royal Canadian Mounted Police had established equity, diversity, and inclusion action plans, there was no measurement of or comprehensive reporting on progress against outcomes for racialized employees in each organization. As a result, the 6 organizations did not know whether their actions had made or would make a difference in the work lives of racialized employees.

Practices for gathering and analyzing disaggregated data were also mixed across the 6 organizations. None examined performance rating distribution or tenure rates for racialized employees, and only some examined survey results and representation, promotion, and retention data at disaggregated levels. These differing approaches make it difficult to track and report on results for racialized employees or progress in inclusion across these federal workplaces.

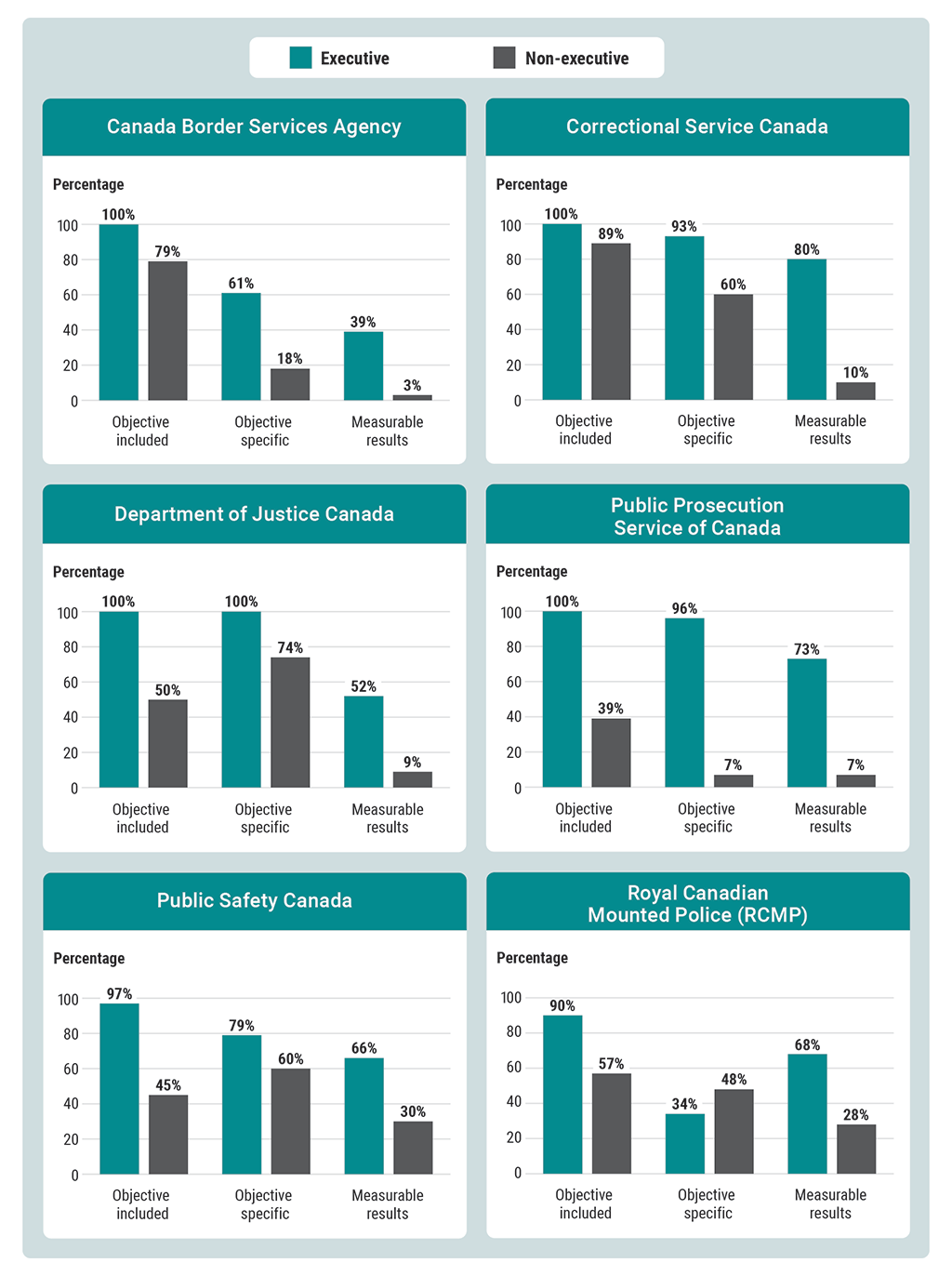

Not using data to understand the lived experiences of racialized employees in the workplace means that organizations and the public service as a whole are missing opportunities to identify and implement changes that could yield improved employment experiences for racialized employees. For example, we found that the 6 organizations we examined did not analyze complaint data to inform how they handled complaints of racist behaviours and related power imbalances despite racialized employees’ concerns about the existing processes. As well, organizations were not always using performance agreements for executives, managers, and supervisors to set expectations for desired behaviours to foster inclusion and create accountability for change. To the racialized employees who volunteered to be interviewed for this audit, these gaps were viewed as a lack of true commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion and left them with the impression that meaningful change was not being achieved.

The 6 organizations we examined had continued to focus on meeting workforce representation goals, including aligning the composition of their workforce with that of Canadian society. While this established approach is an important first step, it is not enough to fuel a sustained shift in organizational culture. Employment equity legislation in Canada has existed since the 1980s, so it alone is not enough to achieve the meaningful change to a workplace that is not only diverse but truly inclusive.

Key facts and findings

- As of 2022, 1 in 5 employees of Canada’s core public administration identified as a member of a visible minority.

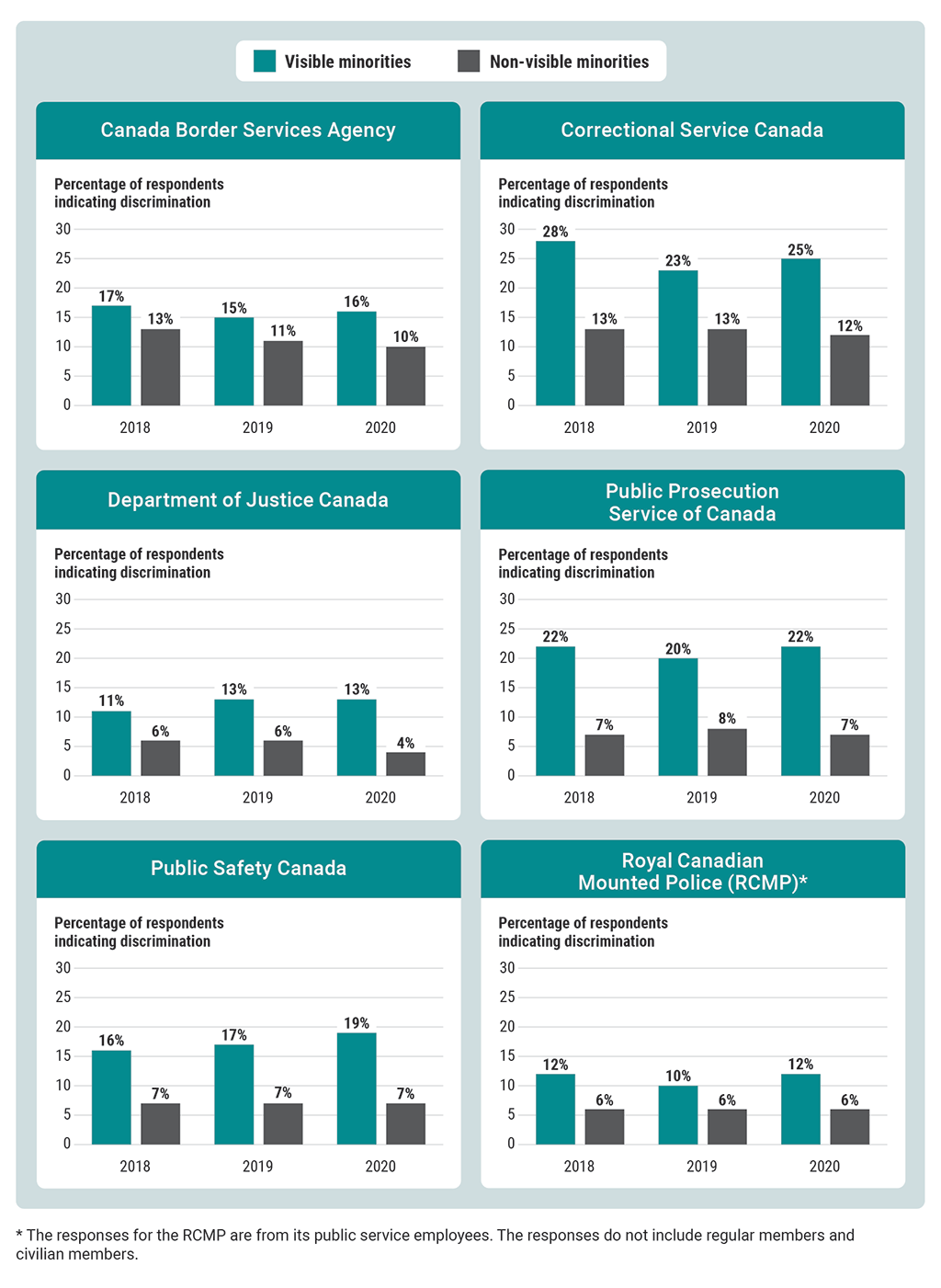

- In all 6 organizations, a higher percentage of visible minority respondents than non‑visible minority respondents indicated in the Public Service Employee Survey (2018–2020) that they were a victim of discrimination on the job.

- The 6 organizations were not making sufficient use of available data to identify barriers faced by their racialized staff or inform equity and inclusion strategies and complaint mechanisms.

- At the manager level, accountability for behavioural and cultural change throughout the different organizations was limited and not effectively measured.

Why we did this audit

- The 6 organizations we audited have a responsibility to provide a work environment that is safe, respectful, inclusive, and free of racism.

- Racialized employees face a unique challenge that stems from a power imbalance derived from being a historically disadvantaged group.

- A representative and inclusive public service draws on the diverse perspectives and lived experiences of disproportionately disadvantaged groups, which in turn better informs decision making and service delivery that impact people.

- Data specific to racialized employees, measured over time, communicated to employee networks, and used by decision makers is necessary to inform actions and provides indicators to track progress toward equity, diversity, and inclusion.

- Access to accurate and timely human resources data to monitor trends and compare them with other available data is required for organizations to identify the impacts of biases and other disadvantages experienced by racialized employees at different levels and throughout an organization.

Highlights of our recommendations

- The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should provide guidance and share best practices that will help organizations establish performance indicators to measure and report on equity and inclusion outcomes in the federal public service.

- All 6 organizations should undertake data-informed analysis to understand how racialized employees experience their workplace in comparison with others. By using quantitative data together with qualitative data, such as the lived experiences of racialized employees and other designated groups, organizations should take concrete and measurable actions to correct situations of employment disadvantage.

- Each of the 6 organizations and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should establish expected behaviours needed for an anti-racist and inclusive work environment and against which performance should be assessed for employees. These behaviours should be aligned with specific equity and inclusion outcome indicators and the performance measurement frameworks.

Please see the full report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

Exhibit highlights

In all 6 organizations, a higher percentage of visible minority respondents than non‑visible minority respondents indicated in the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Public Service Employee Surveys that they were a victim of discrimination on the job

Note: Respondents self‑identified and answered the question: “Having carefully read the definition of discrimination, have you been the victim of discrimination on the job in the past 12 months?”

Source: Based on data from the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Public Service Employee Surveys

Text version

This chart shows the percentage of respondents of the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Public Service Employee Surveys who indicated discrimination at the 6 audited organizations. Respondents self-identified and answered the question: “Having carefully read the definition of discrimination, have you been the victim of discrimination on the job in the past 12 months?” The percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was higher for visible minorities than for non‑visible minorities in all 6 organizations.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 17% | 15% | 16% |

| Non-visible minorities | 13% | 11% | 10% |

At Correctional Service Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 28% | 23% | 25% |

| Non-visible minorities | 13% | 13% | 12% |

At the Department of Justice Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 11% | 13% | 13% |

| Non-visible minorities | 6% | 6% | 4% |

At the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 22% | 20% | 22% |

| Non-visible minorities | 7% | 8% | 7% |

At Public Safety Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 16% | 17% | 19% |

| Non-visible minorities | 7% | 7% | 7% |

At the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows. The responses are from its public service employees. The responses do not include regular members and civilian members.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 12% | 10% | 12% |

| Non-visible minorities | 6% | 6% | 6% |

In the 6 organizations, a greater percentage of respondents from racialized groups compared with those who did not identify as racialized selected the least positive answers in the Public Service Employee Survey (2020 and 2022) questions regarding fear of reprisal

Note: In 2022, respondents self‑identified as belonging to a racial group or not. They answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on my career.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on their career.

In 2020, respondents self‑identified as belonging to a visible minority group or not and answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.

Source: Based on data from the 2020 and 2022 Public Service Employee Surveys

Text version

This chart shows the percentage of racialized and non‑racialized respondents of the 2020 and 2022 Public Service Employee Surveys who did not feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal at the 6 audited organizations. Also shown are the results for the 3 largest racialized subgroups: Black, East/Southeast Asian, and South Asian.

In 2022, respondents self‑identified as belonging to a racial group or not. They answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on my career.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on their career.

In 2020, respondents self-identified as belonging to a visible minority group or not and answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.

At all 6 organizations, a greater percentage of respondents from racialized groups compared with those who did not identify as racialized selected the least positive answers in the survey questions regarding fear of reprisal.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 10% | 13% |

| Racialized | 21% | 25% |

| Black | 31% | 34% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 14% | 20% |

| South Asian | 24% | 25% |

At Correctional Service Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 16% | 16% |

| Racialized | 29% | 33% |

| Black | 38% | 42% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 15% | 25% |

| South Asian | 32% | 31% |

At the Department of Justice Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 7% | 7% |

| Racialized | 23% | 18% |

| Black | 34% | 26% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 18% | 11% |

| South Asian | 25% | 25% |

At the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows. Results are not shown when there is an insufficient number of responses to protect confidentiality of respondents.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 12% | 10% |

| Racialized | 31% | 26% |

| Black | 49% | 34% |

| East/Southeast Asian | Not shown | 13% |

| South Asian | 29% | 52% |

At Public Safety Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows. Results are not shown when there is an insufficient number of responses to protect confidentiality of respondents.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 6% | 7% |

| Racialized | 23% | 29% |

| Black | 47% | 36% |

| East/Southeast Asian | Not shown | 36% |

| South Asian | 34% | 33% |

At the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows. Results reflect public service employees within the organization. The survey does not extend to regular or civilian members.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 9% | 7% |

| Racialized | 18% | 20% |

| Black | 38% | 26% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 16% | 14% |

| South Asian | 16% | 20% |

Performance agreements for executive and non‑executive managers were not always based on specific and measurable objectives and did not always demonstrate results for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals

Source: Based on data from the 6 audited organizations

Text version

This chart shows the percentage of executive and non-executive performance agreements at the 6 audited organizations that included objectives, that had specific objectives, and that had measurable results. Nearly all executive agreements included objectives, but they were not always specific or did not always have measurable results. Non-executive agreements fell below the executive results.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 79% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 61% for executive managers and 18% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 39% for executive managers and 3% for non‑executive managers.

At Correctional Service Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 89% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 93% for executive managers and 60% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 80% for executive managers and 10% for non‑executive managers.

At the Department of Justice Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 50% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 100% for executive managers and 74% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 52% for executive managers and 9% for non‑executive managers.

At the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 39% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 96% for executive managers and 7% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 73% for executive managers and 7% for non‑executive managers.

At Public Safety Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 97% for executive managers and 45% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 79% for executive managers and 60% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 66% for executive managers and 30% for non‑executive managers.

At the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 90% for executive managers and 57% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 34% for executive managers and 48% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 68% for executive managers and 28% for non‑executive managers.

The response rates for the 6 sampled organizations for the Public Service Employee Survey

| Survey yearNote * | Canada Border Services Agency | Correctional Service Canada | Department of Justice Canada | Public Prosecution Service of Canada | Public Safety Canada | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 43.4% | 41.4% | 57.5% | 59.1% | 61.1% | 54.3% |

| 2019 | 49.4% | 47.1% | 51.3% | 58.8% | 70.0% | 58.8% |

| 2020 | 51.8% | 47.0% | 57.6% | 57.2% | 68.8% | 44.2% |

| 2022 | 44.2% | 34.7% | 56.9% | 51.5% | 60.1% | 43.2% |

Source: Based on data from the 2018 to 2022 Public Service Employee Surveys

Highlights:

Racialized employees from the 6 organizations reported rates of discrimination at least 30% higher than non‑racialized respondents in the Public Service Employee Survey.

The 6 organizations all established equity, diversity and inclusion plans to correct the conditions of disadvantage experienced by racialized employees.

Data from organisations was not sufficiently leveraged to guide inclusivity efforts.

Lack of indicators and targets against equity and inclusion means organisations don’t know if they are making progress.

Call to action:

To create a workplace that is truly inclusive, you need to actively engage with your racialized employees, you need to meaningfully use the data you have to inform your decisions, and you need to hold your leadership accountable for delivering change.

Links:

- Clerk’s initial Call to Action

- Clerk’s Call to Action forward direction message to deputies

- Department’s Letters on the Implementation of the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service

- Public Service Employee Survey Results

- Reports: Employment equity in federally regulated workplaces – ESDC Labour Program

- Building a Diverse and Inclusive Public Service: Final Report of the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion

- Canada School of Public Service’s Anti-Racism Learning Series

- Experiences of discrimination among the Black and Indigenous populations in Canada, 2019 (Statistics Canada)

Related information

Entities

Tabling date

- 19 October 2023

Related audits

- 2019 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 1—Respect in the Workplace - 2017 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 4—Mental Health Support for Members—Royal Canadian Mounted Police