2024 Reports 8 to 12 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 12—Canada Summer Jobs—Employment and Social Development Canada

At a Glance

Overall, Employment and Social Development Canada’s Canada Summer Jobs program helped to improve the success of youth in both current and future labour markets. Youth who participated in the program had better long‑term earnings when compared with youth who did not participate in the program. However, the department did not do enough to help youth facing barriers gain employment experience, a key objective of the program. When youth facing barriers, such as Indigenous youth and youth with disabilities, are given equal opportunities to participate in this program, they also have better long‑term earnings.

The Canada Summer Jobs program provides subsidies to eligible employers with the intention to create a summer job that would not otherwise exist. We found gaps and inefficiencies in Employment and Social Development Canada’s design and implementation of the program. Despite the program being described as a job creation program, the department does not collect data to know how many summer jobs the funding created. Also, the department does not require employers to provide financial proof that the summer job would otherwise not be possible without funding.

Key facts and findings

- The Canada Summer Jobs program provides wage subsidies to employers to create jobs expected to result in quality summer work experiences for youth between the ages of 15 and 30 to help them develop and improve their skills.

- Between 2019 and 2023, the Canada Summer Jobs program funded over 460,000 jobs for youth.

- Unemployment rates in Canada have historically been higher for the youth population than for adults. Based on Statistics Canada data, as of August 2024, the unemployment rate for youth (ages 15 to 24) was 14.5%, more than double that of the adult population (ages 25 to 65) at 6.6%.

- One of the Canada Summer Jobs program’s objectives is to prioritize youth facing barriers to employment, particularly those with limited work or no previous job experience. It is also meant to prioritize employers who plan to hire youth who self‑identify as being part of underrepresented groups or having barriers to entering the labour market.

Why we did this audit

- Canada Summer Jobs program is a first job experience that informs future education, training, and career choices. It includes national and local priorities to improve access to the labour market for youth, particularly those who face barriers to employment.

- One of the program’s objectives is to provide wage subsidies to employers so that the youth they employ acquire job experience and skills that will provide them with short- and long‑term economic and career benefits.

- There is an opportunity for the program to increase the number of jobs available to youth facing barriers rather than subsidizing employers for existing jobs.

Highlights of our recommendations

- Employment and Social Development Canada should, for the Canada Summer Jobs program, set targets for supporting youth facing barriers that take into consideration the representation of those youth in each province and territory.

- Employment and Social Development Canada should develop and implement a comprehensive outreach strategy, particularly for national priority youth groups, to help the program reach youth most in need.

- Employment and Social Development Canada should collect and analyze data to determine whether the Canada Summer Jobs program resulted in the creation of new jobs for youth that would not have otherwise existed.

Please see the Link opens a PDF file in a new browser windowfull report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

We found that since 2020, Employment and Social Development CanadaESDC had tracked the contribution of the Canada Summer Jobs program to achieve selected United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals under the Youth Employment and Skills Strategy: Goal 5 (Gender Equality); Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth); and Goal 10 (Reduced Inequalities). However, ESDC had not included the contributions in the key progress indicators for the Youth Employment and Skills Strategy in its departmental results report.

Visit our Sustainable Development page to learn more about sustainable development and the Office of the Auditor General of CanadaOAG.

Exhibit highlights

Unemployment rate (youth 15–24 years of age versus adult population), 2019 to 2024

Source: Based on data from Statistics Canada

Text version

This line graph shows the percentages of unemployment for the youth and adult populations in Canada from 2019 to 2024. Each rate is as of June each year. The unemployment rate for youth is consistently higher than the rate for adults.

In 2019, the percentage of unemployment was 10.7% for youth and 4.7% for adults. In 2020, the percentage of unemployment was 27.8% for youth and 9.9% for adults. In 2021, the percentage of unemployment was 13.9% for youth and 6.9% for adults. In 2022, the percentage of unemployment was 9.3% for youth and 4.3% for adults. In 2023, the percentage of unemployment was 11.4% for youth and 4.5% for adults. In 2024, the percentage of unemployment was 13.5% for youth and 5.2% for adults.

Statistics Canada defines youth as between 15 and 24 years of age, which differs from the age bracket used by Employment and Social Development Canada, which is 15 to 30.

The program used a systematic approach for screening, assessing, and making funding recommendations for employer applications

Source: Based on information from Employment and Social Development Canada

Text version

This flow chart shows the approach used by the Canada Summer Jobs program for screening, assessing, and making funding recommendations for employer applications.

From mid-November to mid-January, employers apply. Not-for-profit, public sector, and private sector organizations with 50 or fewer full-time employees can apply for funds to subsidize a full-time summer position for youth 15 to 30 years old.

From mid-January to mid-March, applications are screened. Each employer’s application is screened for eligibility against 15 mandatory requirements, including application completion, employer and project activities eligibility, job duration and hours, other funding sources, and salary.

In mid-March, applications are assessed. Applications that are screened in are then assessed for the quality of the job based on how well employers will provide quality work experience, provide youth with the opportunity to develop and improve skills, and respond to national and local priorities to improve labour market access for youth who face barriers.

From late March to early April, members of Parliament provide feedback. Members of Parliament, or MPs, receive a list from Employment and Social Development Canada that includes recommendations regarding which employers in their riding should be funded and the level of funding. MPs then provide their feedback on these recommendations based on their understanding of their ridings’ needs.

In mid-April, funding is approved. Employment and Social Development Canada reviews MPs’ feedback and makes the final decision on which applications get approved.

From mid-April to June, results are communicated to employers. Results are communicated to the applicants in mid-April for the first round of funding and in mid‑May to June for the second round of funding.

Finally, in late April to late August, youth are hired. Youth are hired by the approved applicants for the approved period of time (most commonly, 8 weeks) between late April and late August.

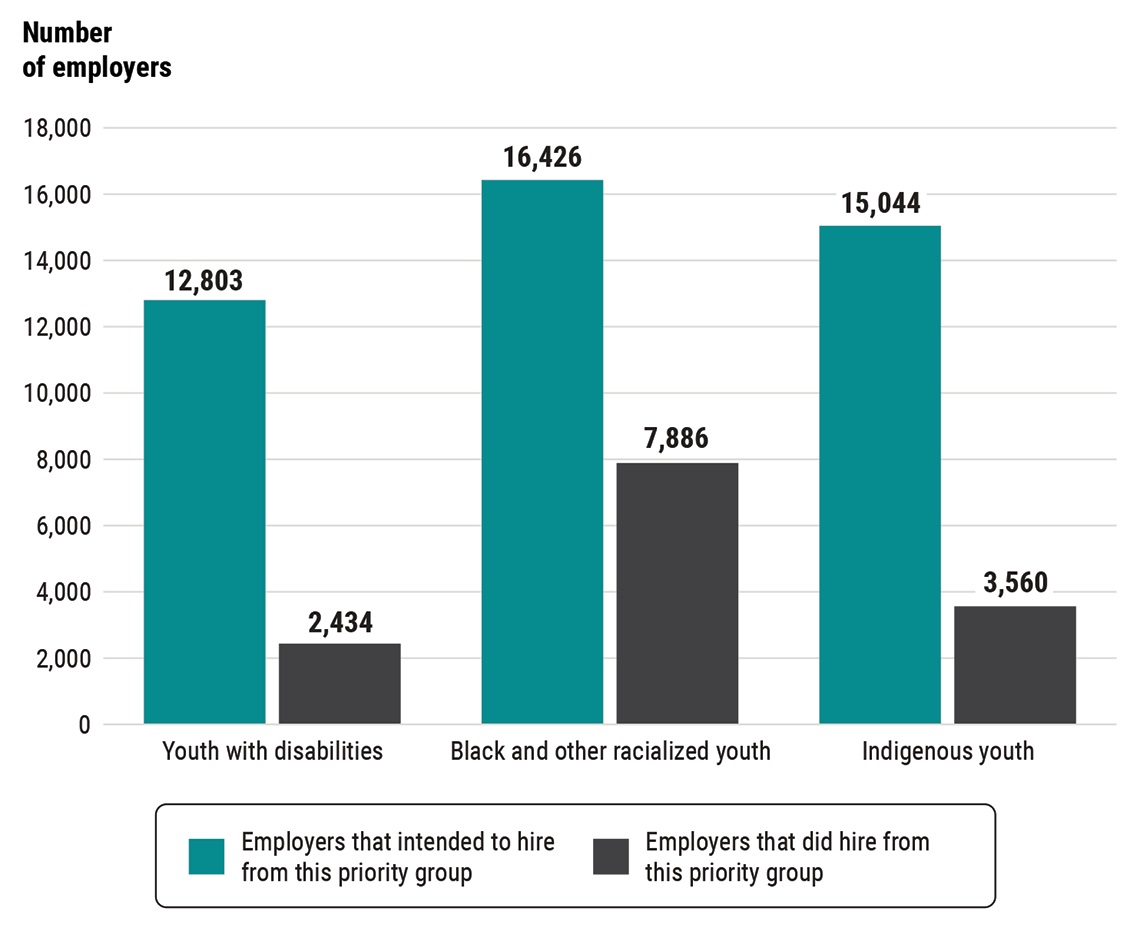

Few employers actually hired from a national priority youth group in 2023

Source: Based on data from Employment and Social Development Canada

Text version

This bar graph compares the number of employers that intended to hire from 3 priority youth groups with the number of employers that did hire from these groups in 2023. The 3 groups shown are youth with disabilities, Black and other racialized youth, and Indigenous youth. For each group, the number of employers that intended to hire was higher than the number of employers that did hire.

For the youth with disabilities group, the number of employers that intended to hire from this group was 12,803, but the number of employers that did hire from this group was 2,434.

For the Black and other racialized youth group, the number of employers that intended to hire from this group was 16,426, but the number of employers that did hire from this group was 7,886.

For the Indigenous youth group, the number of employers that intended to hire from this group was 15,044, but the number of employers that did hire from this group was 3,560.

Related information

Tabling date

- 2 December 2024

Related audits

- 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 6—Employment Training for Indigenous People—Employment and Social Development Canada