COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

4045 Evidence-Gathering Methods

Jul-2020

Overview

In order to plan the audit strategy, the audit team thinks through how it will gather sufficient appropriate evidence to enable it to conclude against the audit objective. This work is documented in the audit logic matrix and further expanded in audit programs. Audit procedures can be incorporated into the ALM or in separate audit programs.

CSAE 3001 Requirements

26. In order to establish whether the preconditions for a direct engagement are present, the practitioner shall, on the basis of a preliminary knowledge of the engagement circumstances and discussion with the appropriate party(ies), determine whether: (Ref: Para. A35–A37)

[...]

(b) The engagement exhibits all of the following characteristics:

[...]

(iv) The practitioner expects to be able to obtain the evidence needed to support the practitioner’s conclusion; (Ref: Para. A51-A53)

[...]

53R. Based on the practitioner’s understanding (see paragraph 51R) the practitioner shall: (Ref: Para. A110-A114)

(a) Identify and assess the risks of significant deviation; and

(b) Design and perform procedures to respond to the assessed risks and to obtain reasonable assurance to support the practitioner’s conclusion. In addition to any other procedures on the underlying subject matter that are appropriate in the engagement circumstances, the practitioner’s procedures shall include obtaining sufficient appropriate evidence as to the operating effectiveness of relevant controls over the underlying subject matter when:

(i) The practitioner intends to rely on the operating effectiveness of those controls in determining the nature, timing and extent of other procedures, or

(ii) Procedures other than testing of controls cannot alone provide sufficient appropriate evidence.

55. When designing and performing procedures, the practitioner shall consider the relevance and reliability of the information to be used as evidence. If:

(a) Evidence obtained from one source is inconsistent with that obtained from another; or

(b) The practitioner has doubts about the reliability of information to be used as evidence,

the practitioner shall determine what changes or additions to procedures are necessary to resolve the matter, and shall consider the effect of the matter, if any, on other aspects of the engagement.

68. The practitioner shall evaluate the sufficiency and appropriateness of the evidence obtained in the context of the engagement and, if necessary in the circumstances, attempt to obtain further evidence. The practitioner shall consider all relevant evidence, regardless of whether it appears to corroborate or to contradict the measurement or evaluation of the underlying subject matter against the applicable criteria. If the practitioner is unable to obtain necessary further evidence, the practitioner shall consider the implications for the practitioner’s conclusion in paragraph 69. (Ref: Para. A147-A153)

CSAE 3001 Application Material

A51.The quantity or quality of available evidence is affected by:

(a) The characteristics of the underlying subject matter. For example, less objective evidence might be expected when the underlying subject matter deals with matters that are future oriented rather than historical; and

(b) Other circumstances, such as when evidence that could reasonably be expected to exist is not available because of, for example, the timing of the practitioner’s appointment, an entity’s document retention policy, inadequate information systems, or a restriction imposed by the responsible party.

Ordinarily, evidence will be persuasive rather than conclusive.

A110. The practitioner chooses a combination of procedures to obtain reasonable assurance or limited assurance, as appropriate. The procedures listed below may be used, for example, for planning or performing the engagement, depending on the context in which they are applied by the practitioner:

- Inspection;

- Observation;

- Confirmation;

- Recalculation;

- Reperformance;

- Analytical procedures; and

- Inquiry.

A111. Factors that may affect the practitioner's selection of procedures include the nature of the underlying subject matter; the level of assurance to be obtained; and the information needs of the intended users and the engaging party, including relevant time and cost constraints.

A112. In some cases, a subject-matter-specific CSAE may include requirements that affect the nature, timing and extent of procedures. For example, a subject-matter-specific CSAE may describe the nature or extent of particular procedures to be performed or the level of assurance expected to be obtained in a particular type of engagement. Even in such cases, determining the exact nature, timing and extent of procedures is a matter of professional judgment and will vary from one engagement to the next.

A113. In some engagements, the practitioner may not identify any areas where a significant deviation is likely to arise. Irrespective of whether any such areas have been identified, the practitioner designs and performs procedures to obtain a meaningful level of assurance.

A114. An assurance engagement is an iterative process, and information may come to the practitioner’s attention that differs significantly from that on which the determination of planned procedures was based. As the practitioner performs planned procedures, the evidence obtained may cause the practitioner to perform additional procedures.

Sufficiency and Appropriateness of Evidence (Ref: Para. 14(j), 68)

A147. Evidence is necessary to support the practitioner’s conclusion and assurance report. It is cumulative in nature and is primarily obtained from procedures performed during the course of the engagement. It may, however, also include information obtained from other sources such as previous engagements (provided the practitioner has determined whether changes have occurred since the previous engagement that may affect its relevance to the current engagement) or a firm's quality control procedures for client acceptance and continuance. Evidence may come from sources inside and outside the appropriate party(ies). Also, information that may be used as evidence may have been prepared by an expert employed or engaged by the appropriate party(ies). Evidence comprises both information that supports and corroborates aspects of the underlying subject matter, and any information that contradicts aspects of the underlying subject matter. In addition, in some cases, the absence of information (for example, refusal by the appropriate party(ies) to provide a requested representation) is used by the practitioner and, therefore, also constitutes evidence. Most of the practitioner's work in forming the assurance conclusion consists of obtaining and evaluating evidence.

A148. The sufficiency and appropriateness of evidence are interrelated. Sufficiency is the measure of the quantity of evidence. The quantity of evidence needed is affected by the risks of the underlying subject matter containing a significant deviation (the higher the risks, the more evidence is likely to be required) and also by the quality of such evidence (the higher the quality, the less may be required). For certain types of direct engagements such as performance audits, there may also be a higher risk of concluding that there is a significant deviation when that is not the case. The appropriateness of the practitioner’s decision regarding whether a matter identified is a significant deviation is affected by the quantity and quality of evidence obtained.

A149. Appropriateness is the measure of the quality of evidence; that is, its relevance and its reliability in providing support for the practitioner’s conclusion. The reliability of evidence is influenced by its source and by its nature, and is dependent on the individual circumstances under which it is obtained. Generalizations about the reliability of various kinds of evidence can be made; however, such generalizations are subject to important exceptions. Even when evidence is obtained from sources external to the appropriate party(ies), circumstances may exist that could affect its reliability. For example, evidence obtained from an external source may not be reliable if the source is not knowledgeable or objective. While recognizing that exceptions may exist, the following generalizations about the reliability of evidence may be useful:

- Evidence is more reliable when it is obtained from sources outside the appropriate party(ies).

- Evidence that is generated internally is more reliable when the related controls are effective.

- Evidence obtained directly by the practitioner (for example, observation of the application of a control) is more reliable than evidence obtained indirectly or by inference (for example, inquiry about the application of a control).

- Evidence is more reliable when it exists in documentary form, whether paper, electronic, or other media (for example, a contemporaneously written record of a meeting is ordinarily more reliable than a subsequent oral representation of what was discussed).

A150. The practitioner ordinarily obtains more assurance from consistent evidence obtained from different sources or of a different nature than from items of evidence considered individually. In addition, obtaining evidence from different sources or of a different nature may indicate that an individual item of evidence is not reliable. For example, corroborating information obtained from a source independent of the appropriate party(ies) may increase the assurance the practitioner obtains from a representation from the appropriate party(ies). Conversely, when evidence obtained from one source is inconsistent with that obtained from another, the practitioner determines what additional procedures are necessary to resolve the inconsistency.

A151. In terms of obtaining sufficient appropriate evidence, it is generally more difficult to obtain assurance about the underlying subject matter covering a period than about underlying subject matter at a point in time. In addition, conclusions provided on processes ordinarily are limited to the period covered by the engagement; the practitioner provides no conclusion about whether the process will continue to function in the specified manner in the future.

A152. Whether sufficient appropriate evidence has been obtained on which to base the practitioner's conclusion is a matter of professional judgment.

A153. In some circumstances, the practitioner may not have obtained the sufficiency or appropriateness of evidence that the practitioner had expected to obtain through the planned procedures. In these circumstances, the practitioner considers that the evidence obtained from the procedures performed is not sufficient and appropriate to be able to form a conclusion on the underlying subject matter. The practitioner may:

- Extend the work performed; or

- Perform other procedures judged by the practitioner to be necessary in the circumstances.

Where neither of these is practicable in the circumstances, the practitioner will not be able to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to be able to form a conclusion. This situation may arise even though the practitioner has not become aware of a matter(s) that causes the practitioner to believe the underlying subject matter may have a significant deviation, as addressed in paragraph 54L.

Financial Administration Act

FAA 138(5) An examiner shall, to the extent he considers practicable, rely on any internal audit of the corporation being examined conducted pursuant to subsection 131(3).

OAG Policy

The audit team shall document how it intends to gather evidence to conclude against the audit objective. [Nov-2011]

When representative sampling is used in a reasonable assurance engagement, at a minimum, audit samples shall be sufficient to attain a confidence interval of 10% and a confidence level of 90%. Sampling for audits of high risk or sensitivity shall be sufficient to attain the confidence interval of 5% and confidence level of 95%. [Jul-2019]

The team shall include in the audit report an informative summary of the work performed as the basis for the practitioner’s conclusion. This summary shall include information on the nature and extent of testing completed. [Nov‑2016]

OAG Guidance

What CSAE 3001 means for evidence gathering methods

The CSAE 3001 requires sufficient appropriate evidence to be obtained in order to support the audit conclusion. It notes that, “Sufficiency is the measure of the quantity of evidence” and “Appropriateness is the measure of the quality of evidence (relevance and reliability).” For more on this topic, see OAG Audit 1051 Sufficient appropriate audit evidence.

The decision on whether a sufficient quantity of evidence has been obtained will be influenced by the risks of the subject matter containing a significant deviation (the higher the risks, the more evidence is likely to be required) and also by the quality of such evidence (the higher the quality, the less may be required). Evidence for an “audit level of assurance” is obtained by different means and from different sources, described below.

The team should also include in the audit report a brief description of the evidence gathering and analysis techniques (OAG Audit 7030 Drafting the audit report), including information on the nature and extent of testing completed. As a good practice, it is recommended that the summary of audit work completed include details of the sampling approach, sample size, and population size. This summary could be included either in the body of the report or in the About the Audit section of the report.

Audit evidence

Evidence is information that is collected and used to provide a factual basis for developing findings and concluding against audit criteria and objectives. Evidence provides grounds for concluding that a particular finding is true by providing persuasive support for a fact or a point in question. Evidence must support the contents of an audit report, including any descriptive material, all observations leading to recommendations, and the audit conclusions. CSAE 3001 defines evidence as “Information used by the practitioner in arriving at the practitioner’s conclusion. Evidence includes both information contained in relevant information systems, if any, and other information. Sufficiency of evidence is the measure of the quantity of evidence. Appropriateness of evidence is the measure of the quality of evidence.”

The audit logic matrix (ALM) (OAG Audit 4044 Developing the audit strategy: audit logic matrix) sets out the methods that the team expects to use for evidence gathering and analysis. It describes how the team will use the evidence to assess whether the criteria have been met, thus allowing it to draw conclusions against the audit objectives. The ALM then guides the development of audit programs, which describe in more detail how the audit team intends to gather evidence (OAG Audit 4070 Audit Program). Audit procedures can be incorporated into the ALM or in separate audit programs.

The audit team needs to collect sufficient and appropriate evidence to support the conclusion in the audit report (OAG Audit 1051 Sufficient appropriate audit evidence). In this context, it is particularly important for audit team members to use multiple sources of evidence to support their audit conclusions, and to document their approach to evidence gathering. Reliable audit findings are obtained from multiple types of evidence that, together, provide a consistent message.

Teams should identify opportunities for gathering quantitative data, such as trends in the productivity of programs being audited, the costs of deficiencies in management practices, savings to government operations or measurable impacts on Canadians. Quantification increases the precision of audit findings, allows for direct assessments of magnitude, and facilitates the assessment of progress against targets. Furthermore, quantitative results are objectively stated making them less subject to differing interpretations by Parliamentarians and boards of directors. Teams should set out plans for obtaining quantitative data and seek advice from the OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis.

Types of evidence

There are four forms of audit evidence used by the OAG.

Physical evidence is obtained by auditor’s direct inspection or observation. This is done by seeing, listening, and observing directly by the auditor, including for example work shadowing, silent observer, videos/photos shot by the auditor, or mystery shopping.

Testimonial evidence is obtained from others through oral or written statements in response to an auditor’s inquiries. Techniques that could be used to gather testimonial evidence include: interviews, focus groups, surveys, expert opinions, and external confirmation.

Documentary evidence is obtained from information and data found in documents or databases. Techniques that could be used to gather documentary evidence include: entity’s documents, file reviews, databases and spreadsheets, internal audits and evaluations, reports from consultants, studies from other jurisdictions, recalculation, and re-performance.

Analytical evidence is obtained by examination and analysis of plausible relations among and between sets of data. These analyses may include statistical analysis, benchmarking and comparisons, or simulation and modelling of quantitative data, as well as text mining or content analysis of qualitative data.

Relevance and reliability of evidence

Audit team members can gather evidence directly. This may be in the form of

-

physical evidence (such as direct observation, photos/video);

-

documentary evidence (such as file review, review of entity documents, review of data found in databases);

-

testimonial evidence (such as surveys, interviews, focus groups, expert opinion); and

-

analytical evidence (data analytics, data mining, regression, and other examination and analyses conducted by the audit team).

Evidence obtained through the team’s direct physical examination, observation, computation, and inspection is generally more reliable than evidence obtained indirectly.

Evidence can also be obtained indirectly when information is gathered by internal audit, experts or third parties, such as that found in reports. Audit team members need to devote considerably more effort when verifying evidence that they will use to support findings and conclusions, than for contextual information.

When teams use information provided by officials of the audited entity as part of their evidence, they should determine what these officials or other auditors did to obtain assurance about the reliability of the information. Teams may find it necessary to test management’s procedures or directly test the information to obtain assurance about the reliability, accuracy, and completeness of the information received. The nature and extent of the auditors’ procedures will depend on the significance of the information to the audit objective and the nature of the information being used. Accepting work or information from others without question is not appropriate and puts the OAG at risk. Before using it for any purpose, the audit team needs to establish the extent that it can rely on the information. Early in the planning phase, the audit team should seek advice on the reliability of IT systems and system-generated information from the OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis.

As required by paragraph 55 of CSAE 3001, the audit team may consider procedures such as:

- Confirming the information has been peer reviewed.

- Performing a comparison of the information with information from an alternative independent external source.

Reliance on the work of internal audit is possible to obtain evidence. To better understand the subject matter and to identify possible audit efficiencies (and, for a special examination, to comply with the FAA), the audit team shall discuss recently completed as well as upcoming audit projects with the entity’s internal audit function. If the audit team identifies opportunities to rely on the work of internal audit, it shall consider whether it is possible to meet the requirements in paragraph 60 of CSAE 3001 (refer to OAG Audit 4030 Reliance on internal audit).

The audit team may also consider relying on the work of experts and external stakeholders (including those engaged by the entity, if any), and assess whether the work performed may be relevant to the scope of the audit. If such opportunities are identified by the team, it must assess whether reasonable assurance can be obtained concerning the expertise, competence, and integrity of the experts, as well as other factors (OAG Audit 2070 Use of experts).

More information on evidence-gathering techniques can be found in the Evidence and Evidence Gathering Techniques Handout.

The Audit team may choose to quote, in the report, information from an external source that was not prepared by the practitioner’s expert, the responsible party’s expert or the internal audit function. This information may be quoted to set the context related to the performance audit, or to support a finding or recommendation in the report. In such cases, it is important that such information be credible.

Factors the audit team may consider in assessing the credibility of information from an external source include:

-

The nature and authority of the external source, for example, a central bank or government statistics office with a legislative mandate to provide information to the public.

-

Whether the entity has the ability to influence the information obtained from the external source.

-

Evidence of general market acceptance by users of the relevance and/or reliability of information.

-

The nature and extent of disclaimers or other restrictive language relating to the information obtained.

Relevance and reliability of evidence to inform audit conclusions

The following are two suggested options that audit teams could consider to ensure that evidence is relevant and reliable.

Entity review of information quality

The best option is to ask the audit entity or source of the data you are using to provide the results of any quality tests they have undertaken on that information. Study or analysis methodology and findings should be examined to ensure its conclusions are valid. In addition, if you are relying on information from the entity database, you should ask the owner of the data for evidence of their quality assurance standards, including regular reports to management on the quality of the data as well as system controls in place that provide reasonable assurance of quality data input and maintenance. The entity could also provide evidence that they have compared their data with other independent sources that confirm its reliability. Positive results from these steps can provide a high level of assurance of data quality.

OAG review of information quality

If the entity or source of data cannot provide documented assurance of information validity and reliability, you may choose to conduct your own review and analysis of the quality of the data you are using. In some situations this may be an appropriate step, particularly when you plan to use the information provided extensively throughout the audit report and if there is a potential risk of material errors in the data. However, a decision to test the data yourself must be predicated on such factors as cost-benefit and our ability to do it. Such a test may require a lot of resources and time, and may be impractical given the circumstances and the time available. If such an option is to be undertaken, it is best planned for and conducted at the outset of the audit and built into the cost of that audit outlined in the audit strategy. Teams planning to conduct their own review and analysis should consult the OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis for specialist guidance and advice.

Relevance and reliability of evidence to support contextual material

In the case of background information, it is not necessary to obtain a high level of assurance; a moderate level of assurance is appropriate. Simple attribution to the source (to an entity or a third party), although always useful and advisable, is not sufficient. Audit teams should attain a moderate level of assurance through enquiry, analysis, and discussion that will enable them to conclude that the information is plausible. To form a sound professional judgment on whether the moderate level of assurance is attained and to determine the plausibility of the evidence to be used, audit teams could follow these steps:

-

Ensure that you have adequate knowledge of the operations and business that underlie the functioning of the database or information source you will be using. In many instances, this is gathered by the audit team over a period of years and audits (knowledge of the business). One aspect is to ensure that you have up-to-date knowledge of the qualifications of those managing the database and the extent to which quality controls are functioning. In addition and where possible, determine whether a reliable party(s) independent of the data source can provide some assurance concerning the quality of the data to be used. This could include information concerning the extent to which other stakeholders and users of the data review the information regularly and are likely to identify and report significant error.

-

Cross check and compare information and findings gathered from your audit work during the planning and examination phases of the audit with the information acquired from outside sources for consistency. This is particularly critical when the external source data used is unaudited.

-

Request from the auditee a formal declaration as to why they believe that the information provided is free from material errors. This can be in the form of a letter or e-mail outlining the factors that they consider best illustrate the quality of the information you are using. Examine the reasonableness of their logic using your knowledge of their operations. The entity may be able to assert through its analysis that the data matches results from other sources or that a variety of stakeholders have a vested interest in the quality of this information and have reason to regularly check its validity and reliability.

-

When using third-party research papers or academic studies, ascertain the implicit controls in place for publication of those documents (for example, the disclosure policy for a journal). Typically, less effort is required to assess the validity of third-party information, as it is normally not used alone to support a finding. The reputation of the developer of the information or data source and the extent to which this source has been proven by wide use are important factors to note. When using reports from other departments and agencies, check to see if our Office has in the past conducted an audit of aspects related to that report, such as report methodology or supporting database controls (e.g. Statistics Canada).

-

When using a number of sources of information (databases, studies, papers, etc.), examine the general consistency of their findings and conclusions. Different information sources providing the same observations can be compelling. It is wise once again to examine these general conclusions with your findings from audit field work.

Meetings and interviews

Meetings and interviews are needed to understand entity operations and to identify potential sources of evidence. However, evidence provided at meetings and interviews reflects the views and opinions of those invited and may be subject to inherent biases. Such evidence should be corroborated by information from other sources.

At times, verbal accounts from meetings and interviews may be the sole source of evidence because other sources do not exist or are unavailable. For example, the entity might be unable to produce documentary evidence or entity officials may claim that certain practices are not followed.

If the audit team intends to rely on verbal accounts for evidence, then it should obtain written confirmation that the notes are an accurate account of what was said in a timely manner—for instance, within two weeks of the interview. If the team intends to rely on verbal accounts only for extracts of the notes, it can obtain confirmation of the extracts by email at that time or later, when it becomes clear that the notes are necessary for audit evidence. The audit teams should consider this option instead of sending the full notes to be reviewed.

The audit team members do not need to obtain sign-off if they are confident that the content of the notes will not be used as evidence to generate findings or conclusions in the audit report.

Audit team members should tell those present at the meeting or interview at the outset that such confirmation may be requested. Disagreement about the notes that cannot be resolved should be documented. Significant unresolved matters related to sign-offs of meeting and interview notes should be referred to the director leading the audit. The director could involve the engagement leader, if required, and can consider raising the matter with the entity principal and/or the entity officials.

Surveys

Surveys can be a cost-effective way of asking individuals about their observations, behaviour, opinions, and perceptions when it is impractical to conduct interviews or focus groups because of the number and availability of people or groups involved and the audit resources available. Surveys provide testimonial evidence and, as do interviews, reflect the interests of the stakeholder group being surveyed. If the audit team plans to use a survey as part of evidence gathering, the audit team should state this and prepare a detailed plan. Teams should seek advice on conducting surveys from the OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis.

Note: The OAG is subject to the Privacy Act and as such, any Canadian citizen or permanent resident can request his or her personal information from the OAG. Thus, auditors should take care not to insert in audit records remarks of a personal nature about individuals encountered during the course of an audit (see OAG Audit 1192 Confidentiality, safe custody, integrity, accessibility, and retrievability of engagement documentation).

Data reliability and analytics

Data analytics fits within the category of analytical evidence. It is receiving increasing attention at the OAG as a powerful set of tools to make strong and compelling observations that are objective and convincing. Data analytics may be based on a sample and rely on statistical inference to conclude on a population, or operate on whole populations directly and thus move from probabilities to certainties.

Big data or population-based approaches can be descriptive in nature; for example, mapping together timelines of multi-stage processes to better understand performance successes and deficiencies, or focussing on building predictive models.

Statistical approaches in data analytics generally rely on building explanatory or predictive models of the processes under examination. Regression analyses can indicate which of a large set of predictor variables are most strongly associated with, and thus predictive of, a criterion or dependent variable of interest. For example, a dependent or criterion variable might be the time it takes to process applications for a government service. By using regression analyses, we can identify which particular attributes of actual applicants and applications are associated with delays.

Data mining is a computationally intensive approach to finding patterns and relationships in large data sets using methods from machine learning, statistics, and artificial intelligence. While data analysis is normally conducted to test specific hypotheses or models or assess particular relationships of interest, data mining generally is not hypothesis driven. Rather, it relies on methods that pull out patterns and relationships that are hidden in a potentially very large set of input variables.

For example, a data mining approach to discover fraud would process the input variables to find the subset that, in a particular combination, optimally distinguishes between the categories of fraud and non-fraud. The challenge with data mining is that it requires a sufficiently large set of known cases, where fraud and non-fraud are known. These known cases form the base on which the predictive model is built.

Understanding of data

The following are important questions audit teams should ask entities, in early planning work, to assess data and to understand the processing underlying that data. The responses to these questions can help audit teams determine risk areas and better plan for and anticipate challenges regarding the reliability of system-generated data later in the audit process:

-

What data do you collect for administrative purposes?

-

How is this data maintained (database systems, Excel or Microsoft Word files, paper)?

- If the data is maintained electronically, is the data entered directly, or is it entered from paper documentation?

- If entered directly, are there other sources for corroborating the data?

-

At what level is the information collected by each data source: at the level of transaction/individual/program, or has it been aggregated?

-

Describe how you obtain assurance on the accuracy and completeness of data.

-

Have your data sources been otherwise assessed for measures of data quality?

-

Have experts or stakeholders taken a position with regard to data quality?

-

Are these experts internal or external to your organization?

-

How do you prevent improper access to the data?

- Do you have controls on entry, modification, and deletion of computerized data?

-

For what purposes is each data source used (e.g. tracking, reporting)?

-

Do you rely on other data sources outside of your primary data repositories such as an Excel log for tracking/reporting?

-

Is there an oversight function for the data sources in your organization that ensures that proper data management practices are maintained?

-

How does that oversight function work?

-

What impact/role do your data sources have with regard to influencing legislation, policy, or programs?

-

Do your data sources capture information that is likely to be considered sensitive or controversial?

-

What is the level of classification of your data sources (unclassified, Protected A, etc.)?

-

With regard to your data, what documentation can you provide us with and how is it maintained (data dictionary, details on data controls, etc.)?

Once they have an understanding, audit teams can obtain relevant data for review. There are some tests that audit teams can do to test the accuracy, reliability, and completeness of the data:

- consistency with other source information (e.g. public/internal reports);

- data checks for

- illegal or out-of-range values;

- gaps in fields that encode dates, locations, regions, ID numbers, registration numbers, etc.;

- missing values;

- examination of controls on the information (conduct walk-throughs);

- attestation from the entity that the entity’s data is fit for use;

- comparison with population totals reported elsewhere.

Sampling and selection of items for review

Audit teams need selection plans for items to review whenever representative sampling (samples) or targeted testing (selections) is used to conclude on an audit objective.

The OAG encourages audit teams to seek advice on selection plans from OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis.

Questions to consider

If your team is considering selecting items to review, see below for a list of questions your team should explore before meeting with the OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis.

Purpose of the selection or sample

-

What audit question does each selection or sample address?

-

What item is the team examining (e.g. file, case, project)?

-

What procedures will the team perform on each item selected?

- How are errors/deviations defined?

-

How will the procedures performed contribute to concluding against the audit objective?

-

Will the selected items be used to conclude on the entire population (representative sampling) or just on the items selected (purposeful selection)?

Population characteristics

-

What population is the team examining? For what period of time?

-

What is the size of the population?

-

How will the entity provide the population for selection to the team (Excel workbook, Access database, physical records stored on-site)?

-

What procedures will the team undertake to provide assurance on the accuracy and completeness of data provided by the entity or through other sources (e.g. review of entity data quality/data assurance program/controls, comparison to control totals, gap analysis, screening for extreme or invalid values)? See the questions listed related to reliability and accuracy of data under the section “Data Analytics.”

- If you’re using secondary evidence for sampling, how will you get assurance on the data integrity of the information you receive from others?

-

Are the characteristics of the population homogeneous? In other words, do they share similar attributes being tested?

- If not, what procedures will the team adopt to address this, particularly if representative sampling is used?

Audit teams should meet with the OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis to explore which type of selection or sampling would be most appropriate for their situation.

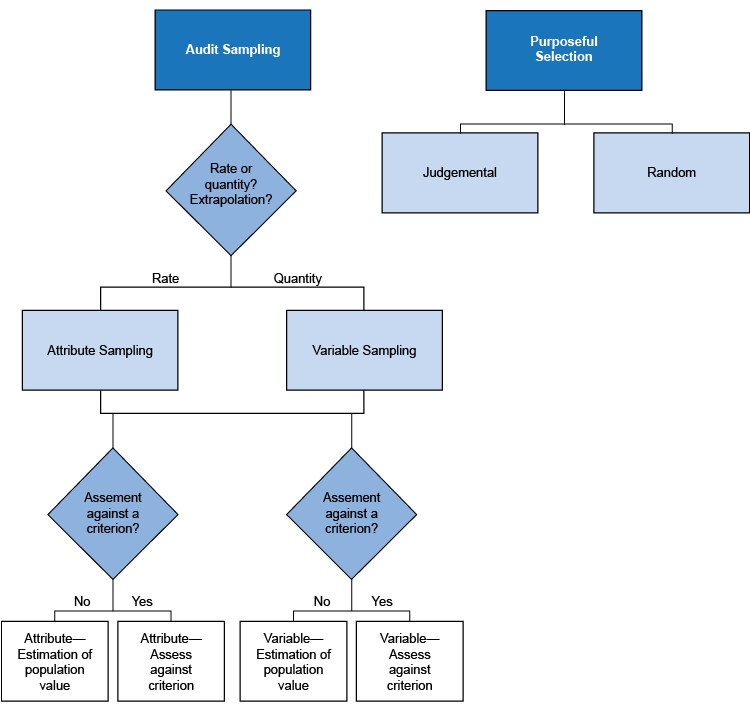

Framework for selecting items to review

Audit teams can rarely examine an entire population of items, which necessitates their review of just a selection. The two fundamental types of selecting or sampling are (1) audit sampling and (2) purposeful selection. Audit sampling is used to conclude on a population of items, whereas purposeful selection is meant to conclude specifically on the items selected, with no statistical basis to conclude on the overall population.

(1) Audit sampling allows audit teams to conclude on a population by examining a sample of items from that population. In this manner, it is also known as representative sampling or generalizable sampling.

Sampling should be considered when

- There is a well-defined population that is relevant to the audit.

- It is impractical to examine the entire population.

- The population is accessible.

- The representation of that population is reliable (i.e. accurate and complete).

- The team has the audit resources it needs.

Audit sampling is very efficient with medium and large populations, but it can be inefficient for small populations. If teams are considering audit sampling with populations of less than 100, they should consult with the OAG Internal Specialist Research and Quantitative Analysis.

The OAG has a policy that all sampling should be performed with a confidence level of 90% or above and a confidence interval of 10% or below. Audits of high-risk areas should consider higher confidence levels and more precise confidence intervals.

There are two types of audit sampling: attribute sampling and variables sampling. Attribute sampling is the sampling approach most commonly used by direct engagement audit teams; variables sampling is rarely used by direct engagement audit teams but is more commonly used for financial audits.

-

Attribute sampling is used to assess the proportion of an attribute of interest to the auditor. An attribute might be whether transactions are in error or not in error, whether individuals are male or female, or whether offices are open or closed. It is not suitable for the extrapolation of amounts, such as dollars in error. This sampling is most often used for direct engagements. Information needed includes confidence interval and confidence level, population size and the expected proportions for the attributes tested (e.g. 50% error / 50% non-error). Note that sample sizes are the largest when the attribute split is roughly 50% / 50%.

-

Variables sampling is used to extrapolate amounts or quantities, such as the amount of error in salary among employees of the OAG. It is not suitable for the extrapolation of the proportion of items in error. This sampling is most often used for financial audit. Information needed includes confidence interval and confidence level, population size, and standard deviation of the selection variable.

Attribute and variables sampling can be applied in two ways:

-

To estimate a population value, such as the proportion of employees with errors in salary payments or the amount of error in salary payments. This sampling is most often used for performance and financial audit. The information needed to estimate population value is the same as specified above in A and B.

-

To assess against a criterion, such as whether the proportion of employees with salary exceeds 10% or whether the amount of error in salary payment exceeds $500 million. Sampling to assess against a criterion may provide efficiencies in performance audit. This sampling is most often used for special examinations and financial audits. The information requirements include those specified above in A and B, as well as expected error and tolerable error.

This type of sampling is intended to assess whether error/deviation in the population has exceeded a specified criterion value. It may not be appropriate to project the extent of error/deviation as an estimate of the population error/deviation. Teams should consult the data analytics and research methods team to learn about this option.

Two forms of this type of sampling are commonly used in the attest practice (they are also used in direct engagements, but rarely):

-

Dollar unit sampling (DUS) and non-statistical sampling (NSS): These are commonly used methods to perform variables sampling to assess against a criterion value. These are regularly used in financial audits, and can increase the efficiency of variables sampling. See the Annual Audit Manual 7044.2 for more information on dollar unit sampling (DUS) and 7044.1 for non-statistical sampling.

-

Controls testing and accept/reject testing: These are common applications of attribute sampling that are regularly used for special examinations and financial audits. Normally, controls testing and accept/reject testing are used when the expected error is 0 or very low. See the Annual Audit Manual 6000 for more information on controls testing and 7043 for accept / reject testing.

-

(2) Purposeful selection is used to comment or conclude specifically on the items chosen for examination. Audit teams performing direct engagements often encounter situations that are more amenable to purposeful selection, not audit sampling. This may be because significant portions of those populations are inaccessible to the audit or the populations consist of many distinct smaller sub-populations. As well, the systems and processes and the controls that are applied to items in these two groups may be entirely different.

Note: Audit teams cannot extrapolate their findings to the overall population. Often, items are selected and examined as case studies, allowing auditors to focus on the particular aspects of each item that made it noteworthy for selection.

There are two types of purposeful sampling: judgmental sampling and random sampling. Direct engagement audit teams often use both approaches.

-

Judgmental sampling relies on specific criteria that the team uses to select individual items for examination or to scope particular types of items for possible selection.

-

Random selection is used when we do not have a particular approach in mind. Often, judgmental selection is used to define a particular set for potential examination, and then random selection is used to choose the actual items for actual examination.

Documenting your sampling plan

Audit teams should document their detailed sampling plan. This plan includes

- a statement about what the evidence will allow the audit team to report,

- the desired accuracy of the results,

- the population size,

- the size of the set of items or sample, and

- the selection or sampling criteria.

Audit teams should seek advice on their selection of items to review from the data analytics and research methods team.

Confidence interval and confidence level

Two measures inform about how effective a sample is likely to be as an estimator of a population: confidence interval (also known as margin of error) and confidence level.

The measure/value generated from a sample is the best estimate of the corresponding population value: for example, if an audit team randomly selected a sample from the population of all vacation leave requests and determined that 33% of them did not have the proper signing authority. The best estimate of the true extent of the lack of proper signing authority in the entire population would then be 33%. But is that best estimate good enough? That is where the measures of confidence level and confidence interval (i.e. margin of error) come in. The team may have looked at only 3 vacation leave requests in a population of 20,000 and found 1 without proper signing authority. That would give a 33% error rate. But it would be difficult to say with confidence that the true error in the population is indeed 33%.

The confidence interval (also known as the margin of error) is the range of values with which the audit team can be reasonably confident that the true population value resides, given the result from the sample. Smaller, or narrower, confidence intervals mean that there is greater precision around the estimate of a population. For example, the narrower confidence interval of +/-5 is more precise than the wider confidence interval of +/-10. In the first case, the audit team may be confident that the true population value lies from 5 below the sample value to 5 above. In the second case, the team would be confident only that the population value rests within the interval from 10 below to 10 above, a much wider range. This wider range means that the confidence interval is less precise.

The confidence interval is the range over which we may be confident that the true population value lies. The confidence level expresses how confident we are. It is a statistical measure of the confidence that the true population value is within the defined confidence interval. The confidence level does not relate to the sample value. It relates to the confidence interval surrounding the sample value.

Confidence level and confidence interval are closely interrelated, and both help to determine what the sample size should be. We typically compute our sample sizes so that we achieve particular targets for confidence interval and confidence level. The OAG has a policy that when representative sampling is used, at a minimum, audit samples shall be sufficient to attain a confidence interval of 10% and a confidence level of 90%. Sampling for audits of high risk or sensitivity shall be sufficient to attain the confidence interval of 5% and confidence level of 95%. Teams compute sample sizes so they can maintain these as our minimum standards.

So, given a sample value of 30% non-compliance, we might say that we are 90% confident that the true population value is between 10 less (20%) and 10 more (40%) using the OAG’s minimum requirements. The sample size must be sufficiently large to support those minimal requirements.

Expected error and tolerable error

Expected error is the best estimate of the error/deviation that exists in a population. Tolerable error is the criterion against which we are assessing the error/deviation we find. For example, if an entity has a performance standard that no more than 20% of transactions take longer than a target of 5 days, then the tolerable error would be 20. Teams might then look at prior years as a guide to expected error. For example, if the average percent of transactions exceeding 5 days for the past three years was 5%, then teams might take 5% as an estimate of expected error. If, however, volume had sharply increased or processing had become more complex, teams might increase the expected error to account for these changes.

As the expected error increases to approach the tolerable error, sample sizes can become very large. However, if teams underestimate expected error, they will need to go back and extend their sample, as the sample is then not sufficient in size to assess the population.