COPYRIGHT NOTICE — This document is intended for internal use. It cannot be distributed to or reproduced by third parties without prior written permission from the Copyright Coordinator for the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This includes email, fax, mail and hand delivery, or use of any other method of distribution or reproduction. CPA Canada Handbook sections and excerpts are reproduced herein for your non-commercial use with the permission of The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“CPA Canada”). These may not be modified, copied or distributed in any form as this would infringe CPA Canada’s copyright. Reproduced, with permission, from the CPA Canada Handbook, The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, Toronto, Canada.

101 Overview of Performance Audits

Aug-2021

Introduction

This overview highlights the key concepts and principles of performance audits conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (the OAG). It also describes the objective and scope of performance audits, and the performance audit process.

The OAG performance audit practice

The characteristics of a successful performance audit are set out in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1—The OAG performance audit practice

Vision

The OAG’s vision is to bring together people, expertise and technology to transform Canada’s future, one audit at a time.

Mission

We serve Canada through leadership and partnerships in audits that support trust in public institutions and continued public service excellence.

Values

The following values define how we conduct our work and ourselves:

- Democracy and independence

- Respect for people

- Integrity and professionalism

- Stewardship and serving the public interest

- Commitment to excellence

The OAG performance audit practice

The objective of the performance audit practice is to contribute to the achievement of the OAG’s Vision and Mission by conducting independent performance audits of government for Parliament and the legislative assemblies of the territories. Performance audits provide assurance and, when appropriate, recommendations for improvement, to assist Parliament and its committees, in particular the Public Accounts Committee, in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

What performance audits are

A performance audit is an independent, objective, and systematic assessment of how well the government is managing its activities, responsibilities, and resources. Performance audits are planned, performed, and reported according to professional standards for assurance engagements (i.e. Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001 for direct engagements) and OAG policies. It is carried out by qualified and independent practitioners. In particular, practitioners should

- establish audit objectives and identify suitable criteria for the assessment of management performance in the areas of government activities to be audited;

- gather the evidence necessary to assess the performance of management against those criteria;

- conclude against established audit objectives;

- make recommendations to management, when appropriate, to deal with significant variances between a criterion (or criteria) and performance; and

- follow up on the recommendations.

Performance audits examine the federal and territorial governments’ programs and/or activities. The “client” for performance audits is Parliament and the legislative assemblies of the territories.

Performance audits seek to determine whether public sector entities are delivering programs or carrying out activities and processes with due regard to one or more of the principles of economy, efficiency, and effectiveness. Performance audits may also focus on the principle of environment and sustainable development.

The principles of economy, efficiency, effectiveness, and environment and sustainable development are defined as follows:

- The principle of economy involves getting the right inputs, such as goods, services and human resources, at the lowest cost.

- Efficiency involves getting the most from available resources, in terms of quantity, quality and timing of outputs or outcomes.

- The principle of effectiveness involves meeting the objectives set and achieving the intended results.

- The principle of environment and sustainable development encompasses sustainable development strategies or management of sustainable development and environmental issues.

The Auditor General Act gives the OAG considerable discretion to determine what areas of government to examine when conducting audits. Performance audits may look at a single government program or activity, an area of responsibility that involves several departments or agencies, or an issue that affects many departments. In determining what to audit, the OAG focuses on areas in which federal organizations face the highest risk. Examples of high-risk areas are those that cost taxpayers significant amounts of money or that could threaten the health and safety of Canadians if something were to go wrong.

Performance audits are conducted as “assurance engagements.” The OAG applies the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001 for direct engagements established by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada). A direct engagement is an assurance engagement in which the practitioner evaluates the underlying subject matter against applicable criteria and aims to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to express, in a written direct assurance report, a conclusion to intended users about the outcome of that evaluation. In the OAG’s case, the intended users are Parliament and the legislative assemblies of the territories. Unlike the OAG’s financial audits, performance audits do not provide assurance on a written assertion provided by an entity (such as a financial statement). Rather, the OAG gives assurance about the conclusions of its audits based on an assessment against the audit criteria. Performance audits also differ from financial audits in that topics change from year to year depending on the risks facing federal entities and the areas of significance to Parliament.

The OAG’s methodology for direct engagements covers all performance audits, including those carried out by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development and audits of territorial governments. In discussing the role of the OAG, references to government and Parliament also apply to the three territorial governments and the territories’ legislative assemblies, unless otherwise stated.

The performance audit methodology does not apply to studies—a form of inquiry that is more descriptive or exploratory in nature than audits. The methodology also does not apply to the Commissioner’s comments on the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, or the Commissioner’s annual report on environmental petitions.

The OAG’s performance audit history

The OAG’s performance audit practice was formalized when Parliament passed the 1977 Auditor General Act. For almost 100 years before the Act was passed, Auditor General reports were intended to focus on financial information. Throughout the history of the OAG, however, Auditors General have reported on whether public money was spent the way Parliament intended; from John Lorn McDougal, the first independent Auditor General of Canada in 1878, who reported on instances of waste, to Maxwell Henderson, Auditor General in the 1960s, who was known for his emphasis on findings of mismanagement and inefficiency.

The Auditor General Act clarified and expanded the Auditor General’s responsibilities. In addition to looking at the federal government’s summary financial statements, the Auditor General was given a broader mandate to examine how well the government managed its affairs and to call attention to anything the Auditor General considers to be of significance and of a nature that should be brought to the attention of the House of Commons. For performance audits, the OAG focuses attention on policy implementation but avoids commenting on the merits of the policies themselves. The application of this principle to a particular audit often requires considerable professional judgment.

An amendment to the Act in 1995 established the position of Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development within the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. On behalf of the Auditor General, the Commissioner has the mandate to report annually to the House of Commons concerning anything that the Commissioner considers should be brought to the attention of the House in relation to environmental and other aspects of sustainable development. In 2005, the “follow the dollar” mandate was inserted into the Auditor General Act, allowing the OAG to audit recipients under a federal funding agreement (excluding other levels of government) that had received at least $100 million in funding over a five-year period. In 2006, however, amendments under the Federal Accountability Act extended the OAG’s mandate to recipients that had received $1 million or more in funding over a five-year period. This amendment gave the Auditor General the powers, at his discretion, to inquire into the use of federal grants, contributions, or loans, even when they are transferred outside government.

Context of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada

Overview of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada

The Auditor General is an agent of Parliament who is independent from the government and reports directly to Parliament. Exhibit 2 illustrates the Auditor General’s role. The Office of the Auditor General is responsible for legislative auditing of the federal and territorial governments. Maintaining the OAG’s objectivity and independence from the organizations that are audited is critical. The Auditor General’s independence is assured by the legislative mandate stated in the Auditor General Act, involving, for example, the freedom to recruit staff and set the terms and conditions of their employment, as well as the right to require the government to provide any information and explanations needed to meet the responsibilities of the Auditor General. The Auditor General is appointed for a 10-year, non-renewable term by the Governor in Council after consultation with the leader of every recognized party in the House of Commons and the Senate, and approval of the appointment by resolution of both the House of Commons and the Senate. In addition, the Office of the Auditor General’s Code of Values, Ethics and Professional Conduct embodies the highest standards of professionalism, objectivity, honesty, and integrity to guide and support OAG employees in all their professional activities.

Exhibit 2—The Auditor General’s role as an Agent of Parliament

Role of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada

The role of the Office of the Auditor General, as external auditor of government, is to assist Parliament in its oversight of government spending and operations. The OAG does this by providing fact-based information obtained through independent audits of federal departments, agencies, and most Crown corporations, which Parliament uses in its scrutiny of government spending and performance.

Activities carried out by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada

In Canada’s parliamentary system, legislatures are responsible for overseeing government activities and holding governments accountable for their handling of public money. The OAG conducts audits that provide objective information, advice, and assurance to Parliament, territorial legislatures, and government—hence the name “legislative audits.” The OAG’s reports and its testimony at parliamentary hearings assist Parliament’s work on the authorization and oversight of government spending and operations.

In addition to performance audits, the OAG carries out two other main types of legislative audits:

- Financial audits

- audits of the federal government’s summary financial statements, which are published annually in the Public Accounts of Canada, and audits of summary financial statements of Canada’s three territories, which are reported to each territory’s legislative assembly. The Auditor General provides an opinion as to whether the summary financial statements of the federal and territorial governments are fairly presented according to their stated accounting policies.

- annual audits of the financial statements of most Crown corporations and many federal organizations, which are reported to the Crown corporations’ board of directors.

- Special examinations of Crown corporations

A type of direct engagement, specifically of Crown corporations. Special examinations are conducted according to the same professional standards for assurance engagements (i.e. Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001 for direct engagements) as performance audits. These reports to a Crown corporation’s board of directors provide an opinion on whether there is reasonable assurance that there are no significant deficiencies in the corporation’s systems and practices that were selected for examination. Under the Financial Administration Act, the board of directors must submit special examination reports to the appropriate Minister and the President of the Treasury Board, and must make the reports available to the public. In its reports tabled in Parliament, the Auditor General reproduces the special examinations that were made public by Crown corporations since the previous tabling of the Auditor General’s reports. The OAG does not conduct special examinations of territorial Crown corporations, but it may include them in territorial performance audits.

The Office of the Auditor General is located in Ottawa, with regional offices in Halifax, Montréal, Edmonton, and Vancouver.

Importance of performance audits

Parliament has three fundamental roles: to legislate, to appropriate funds, and to hold government to account. Parliament expects the government to spend money with due regard to value for money and to measure and report on the effectiveness of programs. The government has an obligation to account to Parliament on its stewardship of taxpayers’ money and on the discharge of its responsibilities.

Independent, objective, and non-partisan performance audits assist Parliament and its committees—in particular, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (or its equivalent in the territorial legislatures), in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs. The audits contribute to maintaining healthy public institutions and a well-managed, accountable government for Canadians.

The Auditor General Act does not define the means by which the performance audit responsibilities are to be discharged. The Auditor General interprets and applies the Auditor General Act when deciding what, how, and when to audit. The Auditor General is answerable to parliamentary committees, including the Public Accounts Committee, on his or her actions in carrying out the responsibilities that have been conferred by the Auditor General Act, the Financial Administration Act, and other laws.

Performance audit reports

The Auditor General submits reports on performance audits to the House of Commons, including follow-up work, which examines progress made by the government in responding to recommendations contained in previous performance audits. Until 1994, the Auditor General’s main instrument for reporting was an annual report to the House of Commons. However, the Auditor General Act was amended in 1994 to allow for the submission of additional reports. The Auditor General’s Reports and the Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development usually consist of several audit reports—one for each performance audit. In the federal system, once these reports are tabled in Parliament, they are automatically referred to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts or the Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development. The Public Accounts Committee is very familiar with the work of the OAG and, as a result, it usually endorses the recommendations in the OAG’s reports and follows up on the suggested approach. In addition to being invited to appear before the Public Accounts Committee and the Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development, the OAG is also invited to hearings with other parliamentary standing committees of the Senate and House of Commons that are charged with oversight of areas that the OAG has audited. The OAG reports performance audits of entities and programs of the territorial governments of Nunavut, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories directly to the respective legislative assembly and appears before various assembly committees.

Objectives and scope of a performance audit

Characteristics of a performance audit

Our performance audits seek to promote well-managed and accountable government operations. Successful performance audits comprise two elements:

- they provide information to Parliament or the legislative assemblies of the territories that is useful to them in carrying out their oversight responsibilities, and

- they result in changes made by government in areas where the Auditor General has found that improvements are needed.

The following are the requirements for a successful performance audit:

- The audit must address matters that add value and that are of a nature to be reported to Parliament. While selecting and submitting audit topics for proposal, audit teams need to identify the expected outcomes of each performance audit and determine what value the audit can add for each of the following areas:

- the assurance that will be provided by the audit;

- the advice (i.e. recommendations) that will be provided by the audit to address gaps, problems, or risks;

- the information that will be provided by the audit to improve transparency or to enhance the understanding of a given situation; and

- any other benefits that the audit will provide.

- The audit must be planned, performed, and reported to meet OAG policies and applicable professional standards. As well, it must be carried out at a reasonable cost.

- It must be clearly communicated in a manner that conforms to professional standards and to OAG reporting practices. The best audit work in the world is wasted if the results are not clearly and correctly communicated to the intended users of the information.

These requirements represent matters that are within the control of the audit team. While they represent necessary conditions for a successful performance audit, achieving all of them is not sufficient. A successful performance audit must also be

- convincing to government, as normally reflected in government’s acceptance of the audit findings and recommendations and in its responses to the post-audit surveys;

- useful to management, as reflected in their implementation of our recommendations;

- useful to parliamentarians, as reflected in

- the use of our recommendations as the basis for parliamentary committee hearings;

- the endorsement of our recommendations, either explicitly or implicitly, by parliamentary committees;

- the use of our work by parliamentarians in the ongoing conduct of their business, such as hearings on reports on plans and priorities and departmental performance reports; and

- the results of our periodic surveys of parliamentarians.

The achievement of these outcomes does not lie wholly within the control of the audit team. However, the team can do much at every stage in the audit to increase the likelihood that these outcomes will occur, and teams are expected to focus on achieving them. Note that the selection of “significant matters” at the early stage of the audit should go a long way to increasing the likelihood of success.

Planning future performance audits

The subject of an audit can be a government entity or activity (business line), a sectoral activity, or a government-wide functional area.

Section 7(2) of the Auditor General Act requires the Auditor General to “call attention to anything that he or she considers to be of significance and of a nature that should be brought to the attention of the House of Commons.” This could include auditing

- the economy or efficiency of the implementation of policy;

- compliance with policy (for example, extent of compliance with a Treasury Board policy);

- the adequacy of the analysis on which a policy or program is based;

- maintenance of accounts or records;

- expenditure of money that has been appropriated for specific purposes;

- safeguarding properties and collecting revenues;

- procedures to measure and report the effectiveness of programs; or

- consideration of the environmental effects of expenditures in the context of sustainable development.

To assist in determining areas to audit, the OAG conducts an analysis for each entity, called the strategic audit planning process. This process involves reviewing entity documents—including entity performance reports and plans, risk analyses, sustainable development strategies, key internal audit and program evaluations—as well as parliamentary and other reports; and conducting interviews with entity management, key external stakeholders, non-governmental experts, and entity officials to find out what they consider to be areas of greatest risk.

Based on the strategic audit plans and previous audit work, the OAG takes a strategic and risk-based approach to selecting performance audit topics, some of which will span several entities, to be conducted over the next few years. The timing and rationale for each audit are important considerations to enable the OAG to fulfill its performance audit mandate.

Strategic audit plans, including the proposed audit topics, are discussed with the Auditor General and the Performance Audit Practice Oversight Committee. Strategic audit plans are reviewed periodically. Planning processes provide opportunities outside of the usual audit process to build relationships with and knowledge of entities. It is also important for audit teams to keep their knowledge up to date through ongoing communication with entities, reviewing entity performance reports and internal audit reports, monitoring Parliamentary committee activity, and media monitoring.

Individual audits are approved by the Performance Audit Practice Oversight Committee through the annual performance audit planning process . Audit topics may also be selected in response to a request from the government or a parliamentary committee, or identified as a priority area by the Auditor General. The audit selection process is described further in OAG Audit 1510 Selection of Performance Audit Topics.

Level of assurance provided

The work reported in performance audit reports is performed at a reasonable level of assurance, which is the highest level of assurance that can be provided concerning a subject matter. Absolute assurance is not attainable because of factors such as the use of judgment, the inherent limitations of internal control, the use of testing, and the fact that much of the evidence is persuasive rather than conclusive.

The CPA Canada assurance standards that apply to the Office of the Auditor General’s performance audits are set out in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance, Canadian Standards on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001 for direct engagements. In a direct engagement, the practitioner evaluates the underlying subject matter against applicable criteria and aims to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to express, in a written direct assurance report, a conclusion to intended users about the outcome of that evaluation. This differs from the reports of financial audits that conclude on whether government financial statements are fairly presented according to their stated accounting policies, or other attestations regarding information prepared by the audited organization. Exhibit 3 lists the CPA Canada standards that apply to the OAG’s performance audits.

Exhibit 3—CPA Canada assurance standards for performance audits

- CSQC1—the Canadian Standards on Quality Control dealing with a firm’s responsibilities for its system of quality control for audits

- CSAE 3001—Canadian standard on assurance engagements that applies to direct assurance engagements

- AuG-50—Conducting a performance audit in the public sector in accordance with CSAE 3001 (supplementary Guideline for CSAE 3001)

In addition to complying with these CPA Canada standards, the OAG has policies in place for aspects of performance audits for which CPA Canada standards do not apply, however these policies are intended communicate legal and other requirements, as well as to help auditors comply with applicable direct engagement standards.

Access to information to fulfill audit responsibilities

For performance audits to Parliament, subsection 13(1) of the Auditor General Act entitles the Auditor General “to free access at all convenient times to information that relates to the fulfillment of his or her responsibilities and he or she is also entitled to require and receive from members of the federal public administration any information, reports and explanations that he or she considers necessary for that purpose.” For performance audits of territorial governments, the Office right of access is governed through the Northwest Territories Act, Nunavut Act, and the Yukon Act, respectively.

The Auditor General decides on the nature and type of information needed to fulfill his/her responsibilities. Further guidance on matters of access is provided in the following documents:

- the Treasury Board Secretariat–OAG communiqué entitled Office of the Auditor General’s Access to Records and Personnel for Audit Purposes (distributed by email to deputy heads on 7 August 2007);

- the Privy Council Office’s Guidance to Deputy Heads, departmental and entity legal counsel and OAG audit liaisons on providing the Auditor General access to information in certain confidences of the Queen’s Privy Council (Cabinet Confidences); and

- the 2010 Protocol Agreement on Access by the Office of the Auditor General to Cabinet Documents (issued by the PCO in May 2010).

The performance audit process

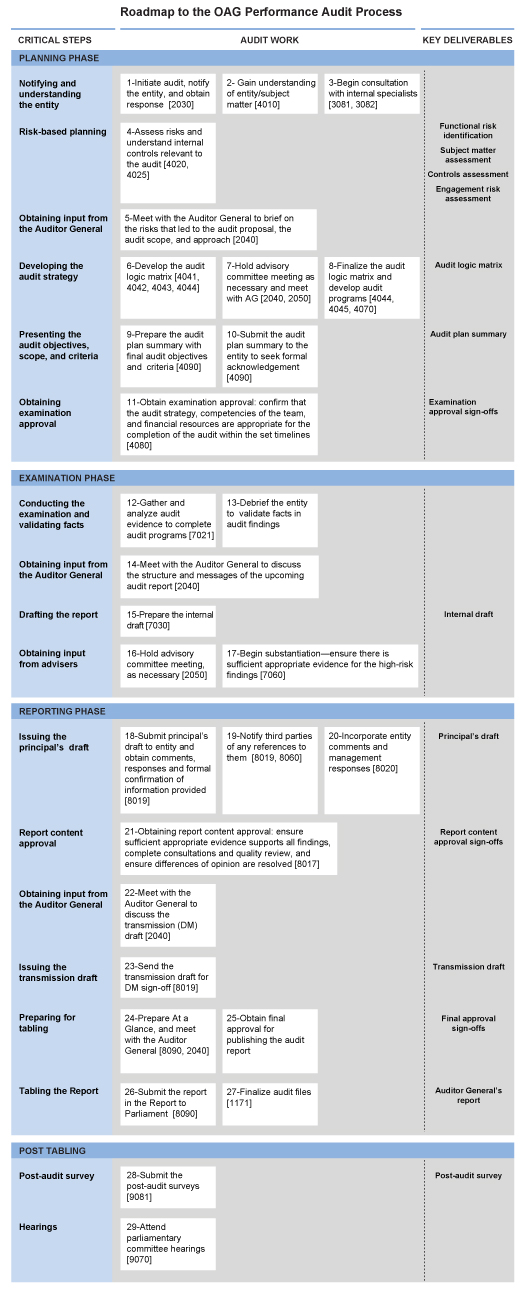

A performance audit has three main phases: planning the audit, conducting the examination, and reporting. The following are critical steps for each of the phases. In practice, these steps often overlap, so are not strictly sequential. Exhibit 4 provides a “roadmap” that summarizes the performance audit process.

Exhibit 4—Roadmap to the OAG performance audit process

Planning phase

Understanding the entity and subject matter. The audit team conducts research and interviews to understand the entity’s mandate and objectives, expected and achieved results, risk profile, organizational structure, activities and operating environment, as well as risks related to the subject matter to be audited. It is important for the team to understand “the big picture.” Forming audit conclusions or reporting weaknesses without this overall knowledge may result in unproductive audit work or misleading findings. To initiate each performance audit, the OAG sends entities to be audited formal letters of notification and solicitor–client privilege. The team establishes constructive working relationships with the entity and adheres to high standards of professional practice in all interactions. Consultations on technical, ethical, or other matters with the OAG’s internal specialists also begin early in the audit and continue throughout all phases.

Risk-based planning. Based on the understanding of the entity and subject matter, the audit team identifies the risks that would prevent the entity’s expected results from being realized and obtains an understanding of internal controls relevant to the audit. The audit team also conducts a risk assessment to determine the audit risks—the risk of making erroneous observations and drawing faulty conclusions and hence making inappropriate recommendations in the report—and how to mitigate the risks by using appropriate audit procedures and other strategies.

Developing audit objective, scope, and criteria. The audit objective states the purpose of the audit and is usually expressed in terms of what questions the audit is expected to answer about the performance of an activity or program. It provides a sense of direction for the audit team and clearly defines what the audit team intends to achieve or conclude at the end of the audit. Scoping the audit identifies the specific issues to be examined and sets the boundaries of the audit, including the time period under audit. The audit criteria are conditions that the entity or function should demonstrate in order for the objective to be met. Selecting suitable criteria is important because the criteria drive the subsequent audit work and reporting. The audit team sets out the objective, scope, and criteria in a key planning document called the audit logic matrix. The examination approval document summarizes the subject matter and issues to be reported.

Presenting the objective, scope, and criteria. At the end of the planning phase, the team drafts the audit plan summary (APS). This document contains the objective, scope, and criteria of the audit, as well as key milestone dates. The team sends the final version to the department or agency to be audited, along with a formal letter from the engagement leader to the deputy head requesting written acknowledgement of entity management’s responsibility for the subject matter as it relates to the audit objective, as well as written acknowledgement that the audit criteria are suitable as a basis for assessing whether the audit objective has been met.

Planning audit work for the examination phase. The team develops audit programs setting out the audit approach and the work that will be necessary to conclude against the audit objective. Audit programs include key questions for each criterion, a list of the type of information required for evidence and the information sources, and methods for data collection and analysis. Audit programs are also a tool for documenting completed work.

Examination phase

Conducting the examination and drafting the audit report. During the examination phase, the team answers the questions in the audit programs by gathering and documenting audit evidence. The team analyzes the evidence to determine whether it is sufficient and appropriate to assess the audit criteria and to conclude against the audit objective. When sufficient and appropriate evidence has been gathered to support clear audit findings, drafting the audit report for internal circulation begins.

Validating facts with entity management. Throughout the examination phase, auditors communicate and verify information with the entity managers responsible for the areas being examined. As the examination phase draws to a close and the audit report is being drafted, the audit team systematically seeks entity management’s views regarding the accuracy and completeness of the facts on which the audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations in the audit report are based.

Obtaining input from advisers. The team seeks advice about the draft audit report from external and internal advisers, as necessary. The advisers provide input on whether the main messages are relevant to Parliament and clearly stated, whether the tone is balanced, what recommendations can be made, and how the structure of the audit report can be improved. Focusing on significance to Parliament, the Auditor General has the final say on the audit report messages, tone and structure, and the appropriateness of conclusions and recommendations.

Substantiating the draft audit report. Throughout the audit, the team maintains a record of all evidence gathered and its sources so that all parts of the audit report can be thoroughly supported. Substantiation is an exercise performed prior to issuing the draft to the entity whereby the evidence is connected to the report sentences. This facilitates an easy retrieval of information and helps the presenter of the report to quickly respond to questions when needed.

Reporting phase

Issuing the principal’s (PX) draft. The entity provides the audit team with comments on the principal’s (PX) draft, after which further revisions may be made. Entity management also provides a first draft of responses to the audit recommendations as well as written confirmation that it has provided all information of which it is aware that has been requested or that could significantly affect the findings or the conclusion of the report. The suitability and practicality of the draft recommendations and responses to them are discussed with entity management. The final versions of these responses are included in the published report.

Issuing the transmission draft. The audit team incorporates final changes into the text that have been agreed to with the entity, as well as the entity responses, and issues the transmission draft to the entity. A formal letter from the engagement leader to the deputy head accompanies this draft, requesting written confirmation that the draft report is factually accurate and that the responses to the recommendations are final.

Preparing for tabling. The final audit report with entity management’s responses is included in the Auditor General’s Report and tabled in Parliament. Because the Auditor General’s reports can be tabled only when Parliament is sitting, tabling dates are planned according to the parliamentary schedule. Following tabling, the audit team ensures that all audit files are finalized in a timely manner.